Among the planets that circle our Sun, none has been as misunderstood or as hauntingly beautiful as Venus. To the naked eye, it shines brighter than any other world—an unblinking jewel in the twilight sky. For millennia, it was associated with love, beauty, and the divine feminine, a celestial counterpart to the morning and evening stars of myth. Yet behind its brilliance lies a hellish truth: Venus is a world of fire and acid, with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead and an atmosphere so dense that it would crush a human explorer in seconds.

And yet, as strange as it seems, this infernal planet may once have resembled Earth. Beneath its oppressive clouds and scorched terrain, Venus hides clues that suggest a far gentler past—perhaps one in which oceans shimmered beneath a blue sky, where rain fell upon continents, and where a mild climate sustained a world not unlike our own.

To ask Did Venus once have oceans? is to confront one of the greatest mysteries of planetary science. It is a question that touches not only on Venus’s history but on the fate of Earth itself. For in Venus, we see what our planet might have become—and what it could still become—if nature’s balance were ever pushed too far.

A Tale of Two Worlds

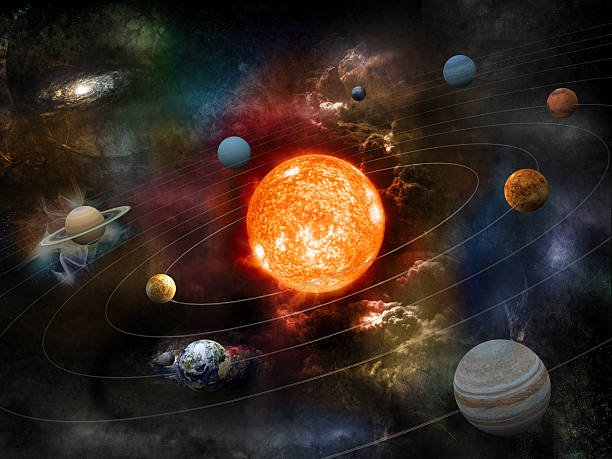

Venus and Earth are often called twins. They are nearly the same size, mass, and composition. Both formed from the same primordial material of the early Solar System, both orbit within the Sun’s so-called “habitable zone,” and both likely began their existence with similar inventories of water and volatile elements. In many ways, Venus should have been a second Earth.

But where Earth blossomed into oceans, forests, and life, Venus became a furnace. Its atmosphere is composed of more than 96 percent carbon dioxide, and its surface pressure is over ninety times that of Earth’s. Temperatures hover around 465°C—hotter than the surface of Mercury, even though Venus lies farther from the Sun. The air is laced with sulfuric acid, and thick clouds perpetually conceal the planet’s face from view.

How did two siblings born from the same cosmic womb take such divergent paths? The answer lies in the delicate interplay between atmosphere, sunlight, and water—the very ingredients that make a world habitable.

The Hints Beneath the Clouds

For centuries, Venus was a mystery. Its brilliant clouds reflected sunlight so completely that early astronomers could see nothing of its surface. They speculated wildly: perhaps it was covered in tropical jungles, or oceans shrouded in mist. Science fiction of the early twentieth century imagined swamps and strange creatures thriving beneath the dense clouds.

That illusion was shattered in the 1960s, when radar imaging and spacecraft missions began to pierce the veil. The first to reach Venus, the Soviet Venera probes, revealed a surface of scorched plains and volcanoes. There were no oceans—only vast basaltic expanses and mountains shaped by unimaginable heat.

Yet even in this inferno, scientists found tantalizing clues. Certain surface features—broad lowland regions and geological patterns—hinted that Venus might once have had flowing water or at least liquid erosion. Chemical data from its atmosphere revealed that hydrogen, a key component of water, was present but severely depleted. This imbalance suggested that much of Venus’s original water had escaped into space long ago.

To understand how and why, scientists had to look deeper into the planet’s atmospheric past.

The Greenhouse Gone Wild

Venus’s modern hellishness is the product of a runaway greenhouse effect—the most extreme example known in the Solar System. A greenhouse effect occurs when a planet’s atmosphere traps heat from sunlight, preventing it from radiating back into space. On Earth, this effect keeps our planet warm enough for life. On Venus, it became a catastrophe.

Early in its history, Venus likely possessed an atmosphere rich in water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen—much like Earth’s primordial air. But because Venus orbits about 30 percent closer to the Sun, it received nearly twice as much solar energy. This additional heat began to evaporate surface water at a faster rate. Water vapor, itself a potent greenhouse gas, trapped even more heat, leading to further evaporation—a feedback loop that spiraled out of control.

As temperatures rose, oceans boiled away, and the water vapor in the atmosphere was broken apart by ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. Hydrogen, the lightest element, escaped into space, while oxygen reacted with surface rocks or formed carbon dioxide. Over millions of years, Venus transformed from a potentially temperate world into a suffocating furnace.

Today, the evidence of this catastrophe is written across its atmosphere. Venus has an extraordinarily high ratio of deuterium (a heavy isotope of hydrogen) to normal hydrogen—about 150 times greater than Earth’s. Because lighter hydrogen escapes more easily into space, this enrichment suggests that the planet once had vast amounts of water that were lost over time.

Oceans That Might Have Been

If Venus once had oceans, what might they have been like? Computer models and climate simulations over the past few decades have attempted to answer this question. These studies suggest that for as long as two billion years after its formation, Venus could have sustained liquid water on its surface.

In 2016, researchers at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies used advanced climate models to simulate the early Venusian environment. Their results were astonishing: assuming a thinner atmosphere and slower rotation (as Venus rotates once every 243 Earth days), they found that the planet could have supported shallow oceans and a mild climate. Clouds would have formed thickly on the dayside, reflecting sunlight and preventing overheating, while global circulation would have distributed heat evenly.

In this vision, ancient Venus might have resembled a tropical Earth—perhaps with steaming seas, rocky continents, and a dense but breathable atmosphere. Over time, however, volcanic activity may have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the air, slowly intensifying the greenhouse effect. As solar radiation grew stronger, the balance tipped, and the oceans began to evaporate.

Some models suggest that this transformation occurred about 700 million years ago—a relatively recent event in geological terms. If so, for most of its history, Venus may have been not a hell, but a paradise lost.

The Volcanic World Beneath the Clouds

Venus today is geologically active. Radar mapping by NASA’s Magellan spacecraft in the 1990s revealed a surface dotted with more than 1,600 major volcanoes—more than any other planet in the Solar System. Though most appear dormant, new evidence suggests that volcanic activity still occurs.

In 2023, data from radar images taken decades apart revealed signs of changing lava flows and collapsing volcanic vents. These observations hint that the planet’s surface is being renewed by fresh eruptions, releasing carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere.

This volcanic vigor could have been central to Venus’s transformation. If massive eruptions over hundreds of millions of years released enough greenhouse gases, they might have overwhelmed any remaining capacity for the planet to regulate its temperature. Without oceans or plate tectonics to recycle carbon back into rocks—as Earth does through the carbon cycle—Venus would have been doomed to heat beyond recovery.

Volcanism also affects the planet’s atmosphere in another way. Sulfur compounds ejected by eruptions contribute to the dense clouds of sulfuric acid that now envelop the planet. These clouds reflect much of the sunlight, paradoxically keeping the upper atmosphere cool even as the surface broils beneath their insulating effect.

The Lost Water and the Dying Sky

The story of Venus’s oceans is inseparable from the story of its water’s disappearance. Every molecule of water vapor that once filled its air was ultimately split by sunlight. In the process, hydrogen atoms escaped into space, and oxygen was left behind to react with minerals.

The absence of water has consequences beyond dryness. On Earth, water acts as a thermostat, moderating climate and enabling the carbon cycle that regulates atmospheric carbon dioxide. It also allows for erosion, sedimentation, and the slow recycling of planetary crust. Without water, Venus’s surface became static and unchanging. Rocks baked under intense heat, and any organic chemistry that might have emerged was obliterated.

The planet’s current atmosphere—dense, choking, and nearly devoid of oxygen—is a relic of this dehydration. Above it, the sky glows with strange luminescence. Lightning flashes through the sulfuric clouds, and winds race around the planet at hurricane speeds. Though we think of Venus as still, it is a world of violent motion, its air roiling in endless turbulence.

Even so, the upper atmosphere holds intriguing surprises. Recent missions have detected water vapor, carbonyl sulfide, and even trace gases like phosphine—a molecule that, on Earth, can be produced by biological processes. While this finding remains controversial, it has reignited interest in Venus as a world that may still harbor mysteries in its cloud tops, even if its surface is dead.

Ancient Venus and the Seeds of Life

If Venus once had oceans, could it have supported life? The conditions necessary for microbial existence—liquid water, stable temperatures, and a moderate atmosphere—may have been present for hundreds of millions, or even billions, of years.

In that early epoch, Venus might have been teeming with shallow seas, mineral-rich sediments, and chemical gradients capable of driving the reactions that lead to life. If primitive life ever arose there, it may have shared a common ancestry with life on Earth. Meteorites ejected by impacts on either planet could have carried microbes between them—a process known as panspermia.

As Venus heated, such life would have faced extinction on the surface. Yet it might have retreated into the clouds, where conditions remain comparatively mild. At altitudes of about 50 kilometers, temperatures hover around 30°C, and pressures are similar to Earth’s. Could microbial life have found refuge in this aerial layer, suspended among droplets of sulfuric acid?

No direct evidence yet supports this possibility, but it remains a compelling line of inquiry. Future missions aim to analyze the Venusian atmosphere in detail, searching for organic compounds, isotopic patterns, or anomalous chemistry that could hint at biological activity.

Lessons from the Sister Planet

Venus offers a mirror through which we can see not only its past but also our potential future. The greenhouse catastrophe that consumed Venus serves as a cosmic warning—a glimpse of what might happen to Earth if our own balance of climate and atmosphere were to falter.

On Earth, the concentration of carbon dioxide continues to rise due to human activity. While our planet’s oceans and biosphere act as stabilizing agents, they are not infinite. If the natural regulatory systems that control temperature were overwhelmed, a runaway effect, though less extreme than Venus’s, could begin. The history of Venus reminds us that habitability is fragile, and that the line between paradise and inferno can be crossed.

At the same time, Venus’s story offers hope. Understanding how and why it changed can deepen our grasp of planetary evolution, atmospheric dynamics, and climate resilience. It also teaches humility: life as we know it depends on a delicate harmony that even our nearest planetary twin could not sustain.

The Return to Venus

After decades of neglect, Venus is once again at the forefront of exploration. NASA, the European Space Agency, and other international teams are preparing a new generation of missions designed to unlock its secrets.

NASA’s VERITAS and DAVINCI missions, scheduled for launch in the coming decade, will map Venus’s surface with unprecedented precision and analyze its atmosphere from orbit to ground. VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy) will reveal the planet’s geological history, searching for evidence of past tectonic and volcanic processes that might explain its lost oceans. DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) will plunge through the atmosphere, measuring its composition and structure to reconstruct how it evolved.

The European Space Agency’s EnVision mission will complement these efforts, focusing on how Venus’s surface and interior interact with its atmosphere. Together, these explorations promise to paint the most detailed picture yet of our enigmatic sister planet.

Reimagining the Blue Venus

Scientists have long speculated about what early Venus might have looked like. Picture a world bathed in golden sunlight, with vast oceans stretching between rugged continents. Volcanic islands exhale steam into a humid sky, and clouds drift lazily above tranquil seas. The atmosphere, thick with nitrogen and water vapor, glows faintly blue.

Perhaps shallow coral-like structures grew in those primordial waters, or chemical reactions in volcanic lagoons gave rise to simple organic molecules. Over time, the slow accumulation of greenhouse gases began to warm the planet, and the seas began to retreat, hissing into vapor as the surface boiled. The last droplets of rain evaporated into the rising heat, and the oceans vanished forever, leaving only barren plains of blackened rock.

What remains today is a fossil of that lost era—a world preserved at the moment of its undoing. Yet even in its ruin, Venus tells a story of cosmic balance and transformation, of how the same physical laws that nurture life can also extinguish it.

The Edge of Habitability

Venus lies at the inner boundary of the Sun’s habitable zone—the region where conditions might allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. Understanding how Venus crossed the threshold from habitable to hostile helps refine our search for life beyond the Solar System.

When astronomers study exoplanets orbiting distant stars, many of them find worlds similar in size and temperature to Venus. These “exo-Venuses” are common, and learning how to distinguish a true Earth analog from a Venus-like imposter is crucial. The key lies in understanding atmospheric composition, cloud dynamics, and thermal balance—all lessons Venus provides in abundance.

In this way, Venus serves as both a warning and a guide. It shows that habitability is not merely a matter of distance from a star, but of complex feedbacks between water, rock, and atmosphere. A planet’s fate depends on how these elements interact—a fragile equilibrium that can endure for billions of years or collapse in an instant.

The Planet That Reflects Ourselves

There is something hauntingly poetic about Venus. Its brilliance has always fascinated humanity, but that same light hides a world destroyed by its own heat. It is as though the planet itself were a mirror, reflecting our deepest anxieties about the fragility of our home.

When we look at Venus through telescopes, we see both a warning and a possibility. It warns us of what happens when a planet’s climate spirals beyond control—but it also reminds us of what might have been. Somewhere in the deep past, Venus could have sparkled with oceans and clouds, its landscapes alive with chemical potential. It was not always a world of death.

In that sense, the question Did Venus once have oceans like Earth? is not just about Venus. It is about us—about how thin the thread of habitability truly is, about the forces that sustain or destroy life, and about the destiny of worlds.

The Eternal Question

The mystery of Venus’s oceans remains unresolved, but every discovery brings us closer to an answer. The isotopes of hydrogen whisper of vanished water; the shapes of its mountains hint at ancient tectonics; the chemistry of its atmosphere recalls a planet that once breathed differently.

Perhaps one day, a probe will descend through the clouds and land on the Venusian surface, drilling into ancient rock and uncovering minerals that can only form in water. Perhaps we will find sediments, or isotopic ratios, that speak unmistakably of oceans long gone. And perhaps, just perhaps, we will find traces of something more—a signature of life that once glimmered there before the fire consumed it.

Until then, Venus remains a riddle—a radiant enigma shining in the sky, both beautiful and tragic. It stands as Earth’s sister, its reflection and its warning, a world that once may have shared our destiny and then lost it.

The World That Burned

Venus is a testament to the power and peril of planetary transformation. It began as a twin to Earth, adorned with water and clouds, but became a furnace through the inexorable laws of physics. Its story is the story of a balance lost, of oceans that boiled away and skies that thickened into poison.

And yet, in its silence, Venus still speaks. It tells us that life is fragile, that worlds are mutable, and that the same sunlight that warms can also destroy. It urges us to cherish the delicate equilibrium that sustains our blue planet—to protect the oceans that still shimmer under our sky.

For perhaps, in the shimmering clouds of Venus, there once were reflections of waves, of rain, of possibility. And though the waters have long vanished, their memory lingers in every atom of that world’s searing air, a cosmic echo of what once was—a paradise lost, and a warning eternal.