Few questions pierce as deeply into the heart of reality as the question of time. What is time? Is it a river flowing endlessly forward, carrying all things with it? Or is it an illusion—something our minds create to make sense of change and motion? Time governs every breath we take, every beat of the universe, yet when we try to define it, it slips through our grasp like water through open hands.

We live by time. We measure our days, our years, our lives in its passing. Clocks tick, seasons turn, and our memories fade into the past as new moments emerge. Yet physics, that grand decipherer of nature’s secrets, offers an unsettling possibility: time may not exist in the way we imagine. It might not “flow” at all. It may not even be a fundamental ingredient of reality.

From ancient philosophers to modern physicists, time has been both a mystery and a mirror—reflecting our deepest intuitions about change, existence, and causality. To ask whether time exists is not merely a scientific question; it is a question about the essence of reality itself.

The Birth of a Concept

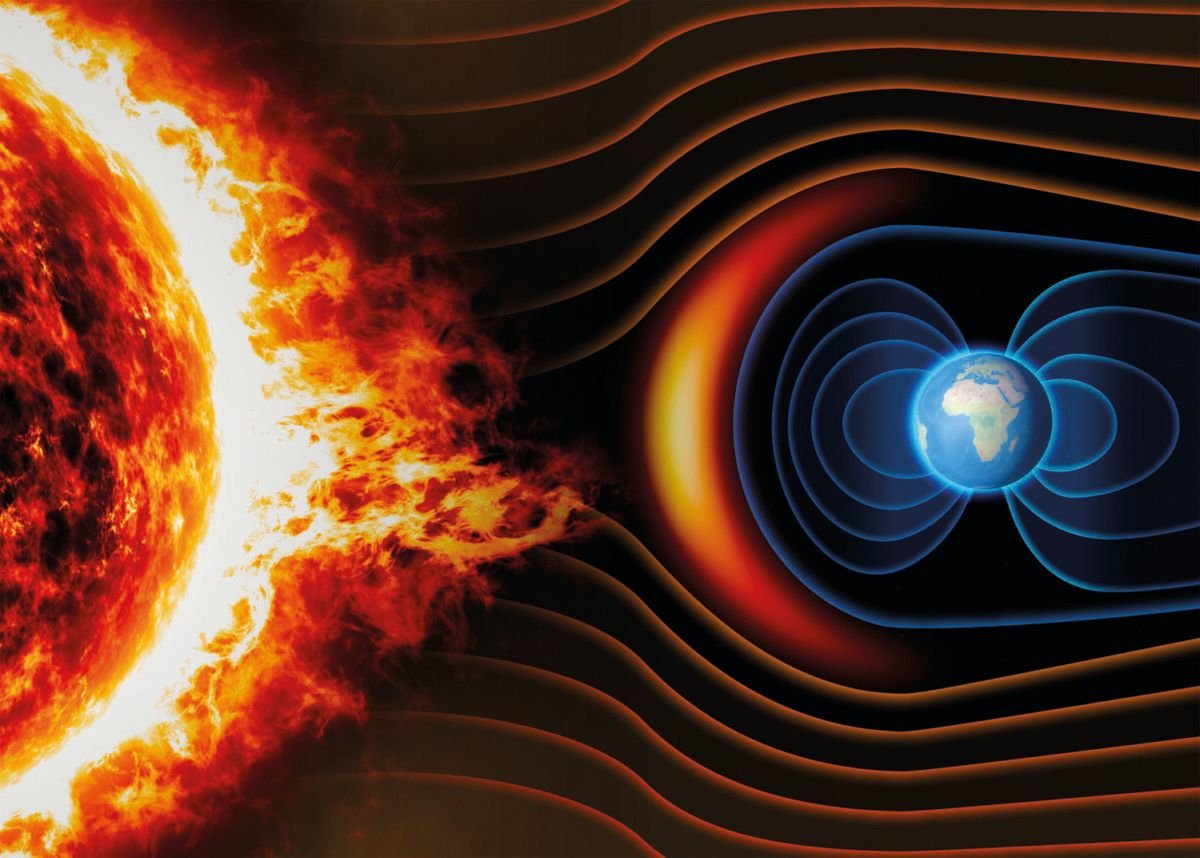

Human awareness of time began not in theory but in observation. The earliest humans watched the Sun rise and set, saw the Moon wax and wane, and marked the seasons by the shifting of stars. From these celestial patterns emerged the first calendars, the first clocks, the first understanding that life unfolds in cycles.

The ancient Egyptians measured time with sundials and water clocks. The Babylonians divided hours into sixty minutes, minutes into sixty seconds—a system still used today. Time was linked to the heavens, to divine order, to the predictable rhythm of celestial bodies.

Philosophers, too, wrestled with its nature. Heraclitus declared that “everything flows,” implying that time was the essence of change itself. Parmenides, his philosophical rival, argued that change is an illusion—that true reality is timeless and unchanging. Plato imagined time as “the moving image of eternity,” while Aristotle described it as “the measure of change in respect of before and after.”

These early thinkers intuited what modern physics would later confirm: time and change are deeply intertwined. But they also sensed something paradoxical—time seems to exist because things change, yet change is only recognizable because time exists.

Newton’s Clockwork Universe

The modern concept of time took shape in the 17th century with Isaac Newton. To Newton, time was absolute—an invisible backdrop against which the universe played out its motions. It flowed uniformly, unaffected by anything that happened within it. Just as space provided the stage for physical events, time provided the rhythm.

In Principia Mathematica, Newton wrote, “Absolute, true, and mathematical time, of itself and from its own nature, flows equably without relation to anything external.” This vision of time as a cosmic metronome fit perfectly with the emerging mechanical worldview. The universe was a grand clockwork, every motion predictable if one knew the positions and velocities of all objects.

In Newton’s world, past, present, and future were clearly distinct. The laws of motion were deterministic—if you knew the state of the universe at one moment, you could calculate its entire history and destiny. Time was the universal ruler by which all motion was measured.

For over two centuries, this view seemed unassailable. It matched experience, explained celestial motions, and formed the foundation of classical mechanics. But as the 20th century dawned, the clock began to crack.

Einstein and the Death of Absolute Time

In 1905, a young patent clerk named Albert Einstein shattered the Newtonian illusion of absolute time. His special theory of relativity revealed that time does not flow identically for everyone—it depends on motion. Two observers moving at different speeds will measure different durations between the same events.

The faster one moves, the slower time passes relative to a stationary observer. This phenomenon, known as time dilation, has been confirmed countless times through experiments with high-speed particles and atomic clocks aboard satellites. Time, once thought absolute, is relative to the observer.

Einstein’s later general theory of relativity deepened the mystery. He showed that gravity is not a force acting through space but the curvature of space and time itself—a unified fabric known as spacetime. Massive objects like stars and planets bend this fabric, and clocks run slower in stronger gravitational fields. Time, therefore, is not a universal flow but a flexible dimension intertwined with space.

In Einstein’s cosmos, time and space are not separate entities. They form a single four-dimensional continuum where past, present, and future coexist. The universe, as described by relativity, is a “block universe,” in which all moments—past, present, and future—are equally real. From this viewpoint, the passage of time is not fundamental but an illusion of consciousness moving along the timeline.

The Block Universe: Where Time Doesn’t Flow

The idea of the block universe challenges our deepest intuitions. If all moments exist simultaneously, then the future is as real as the past, and “now” has no special status. Time does not flow—it simply is. The entire history of the universe, from the Big Bang to its distant future, exists like a cosmic sculpture frozen in four-dimensional spacetime.

In this picture, we are not travelers moving through time; we are patterns of events embedded within spacetime. The sense of motion—from past to future—is an emergent illusion produced by the structure of our brains, which encode memories in one direction. The “flow” of time, then, is psychological, not physical.

This concept is deeply unsettling, for it seems to erase free will and change. If the future already exists, how can choice or causation have meaning? And yet, from a purely relativistic perspective, the laws of physics make no distinction between past and future. They are time-symmetric. Whether time “moves forward” or “backward,” the equations remain valid.

Still, our experience of time’s direction is undeniable. We remember the past, not the future. We see broken eggs but never reassembled ones. Entropy increases. Something fundamental distinguishes yesterday from tomorrow. But what?

The Arrow of Time

If the laws of physics are reversible, why does time seem to move only in one direction? The answer lies in entropy—the measure of disorder in a system—described by the second law of thermodynamics. This law states that in any closed system, entropy tends to increase over time.

When a glass shatters, the pieces scatter into countless configurations—far more numerous than the single ordered state of an intact glass. Reassembling it would require a precise reversal of every atomic motion, something nature almost never does. The forward march of entropy gives time its arrow, marking the difference between past and future.

In this sense, the direction of time arises not from fundamental laws but from initial conditions. The universe began in a state of extraordinarily low entropy—a highly ordered configuration during the Big Bang. As it evolves, entropy increases, creating the asymmetry we experience as the passage of time.

Why the universe started in such a low-entropy state remains one of the greatest mysteries in cosmology. Some theorists propose that time itself emerged at the Big Bang, flowing outward as entropy increased. Others suggest that the universe’s beginning was timeless—a quantum fluctuation from which both time and space crystallized.

Time Before Time: The Birth of the Universe

Can we speak meaningfully of time before the Big Bang? In Einstein’s general relativity, time and space are inseparable; if space began at the Big Bang, so did time. Asking what came “before” may be as meaningless as asking what lies north of the North Pole.

Yet quantum cosmology, which seeks to merge quantum mechanics with general relativity, paints a subtler picture. In the Planck epoch—the first (10^{-43}) seconds after the Big Bang—quantum fluctuations dominated the fabric of spacetime. In this realm, the distinction between past and future may not have existed. Time, as we know it, could have emerged only as the universe cooled and expanded.

Some physicists, such as Stephen Hawking, proposed the “no-boundary” model, in which the universe has no temporal beginning—it is finite but unbounded, like the surface of a sphere. Others, including Carlo Rovelli, argue that time is not fundamental at all but an emergent property arising from quantum correlations between systems. In such a view, time is not something that exists everywhere but something that arises locally when change can be measured.

If this is true, then time is not a universal river flowing through all things, but a reflection of relationships—an emergent illusion that arises only when matter and energy interact.

Quantum Time: The Uncertainty of Now

Quantum mechanics further complicates our understanding of time. At the microscopic level, particles exist in superpositions—multiple states at once—until observed. Events do not unfold in a linear sequence; they are probabilistic, governed by wave functions that describe all possible outcomes.

The quantum world is indifferent to the arrow of time. The equations describing particle interactions are time-reversible. In principle, one could run them backward and obtain equally valid results. Yet when we observe the world, we see definite outcomes, not superpositions. The act of measurement appears to introduce direction—to collapse possibilities into a single realized moment.

This has led some physicists to speculate that the flow of time may emerge from quantum entanglement and decoherence. When quantum systems interact, their correlations increase, producing the appearance of temporal order. Time, in this sense, may be a measure of the growth of quantum information.

In recent years, theories such as the “thermal time hypothesis” suggest that time arises from statistical states rather than fundamental geometry. According to this view, time is not a background parameter but a relational quantity—something that depends on the changing correlations between physical systems.

If these ideas hold true, then time does not exist independently of the universe’s contents. It is not a stage upon which reality unfolds—it is one of reality’s own creations.

The Psychological Illusion of Time

While physics questions time’s objective existence, neuroscience explores its subjective reality. Our perception of time is inseparable from consciousness. The brain does not experience time continuously but constructs it moment by moment through memory and anticipation.

When we recall the past or imagine the future, the same neural networks activate. This suggests that the mind treats time as a spatial landscape through which it can move. The present, then, may be an illusion created by the brain’s synchronization of sensory inputs and memory.

Studies have shown that emotional states, attention, and even body temperature can alter our sense of time’s flow. Fear makes moments stretch; joy makes them fly. This subjectivity implies that what we call the “flow” of time is not a feature of the universe, but of human cognition.

Perhaps our experience of time is like watching a film. The frames—the events of spacetime—already exist. Our consciousness, moving sequentially through them, creates the illusion of motion. We feel time passing not because it flows, but because we do.

The End of Time?

If time began with the Big Bang, will it also end? Cosmology suggests several possible fates for the universe, each carrying profound implications for time itself.

If dark energy continues to drive accelerated expansion, galaxies will drift apart until even starlight cannot cross the cosmic gulf. In this “heat death,” entropy reaches its maximum, and all processes cease. With no change, no motion, no events, time—as measured by change—would lose meaning.

Alternatively, if gravity eventually halts expansion, the universe might collapse in a “Big Crunch.” In such a scenario, time could reverse its arrow, entropy decreasing as the cosmos contracts. Some models even propose a cyclical universe, in which each Big Bang follows a Big Crunch, and time renews itself endlessly.

In the most radical interpretations of quantum gravity, time may not exist at all in the universe’s deepest layer. At the Planck scale, the equations governing the cosmos do not contain a variable for time. Instead, they describe relationships between states—timeless configurations from which temporal order emerges only at macroscopic scales.

If this is true, then time is not fundamental but secondary—a shadow cast by deeper laws that have no beginning or end.

The Philosophical Dilemma

The idea that time might not exist strikes at the core of human intuition. We live in time, grow old in it, love and lose within its passage. Without time, how can there be change, experience, or meaning?

Philosophers have long grappled with this paradox. Saint Augustine wrote, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it, I know not.” He suggested that time exists only in the mind: the past in memory, the future in expectation, and the present as awareness.

Modern philosophers such as Henri Bergson argued that physics describes time as quantity, but consciousness experiences it as quality—a living flow called duration. Einstein disagreed, insisting that “the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” Yet both may be right: physics reveals time’s geometry, while consciousness gives it texture.

Perhaps time exists not as an external entity but as a bridge between the mathematical and the experiential—a meeting point between the universe and the mind that perceives it.

Time and the Self

Our sense of identity is bound to the continuity of time. We remember who we were and anticipate who we will be. If time were an illusion, would selfhood also dissolve?

Neuroscience hints that the self is not a fixed entity but a dynamic process—an ever-updating narrative constructed by the brain. Just as time may emerge from change, the self may emerge from memory. We are not beings who move through time, but temporal beings whose very existence depends on its perception.

In this light, time and consciousness are inseparable mirrors. To experience time is to experience selfhood; to question time’s reality is to question what it means to exist.

Time as Creation

What if time is not something we move through, but something we create? Every moment of awareness, every act of observation, may carve the fabric of reality into “before” and “after.” In quantum terms, each measurement collapses a wave of possibilities into one actualized event, giving rise to a sequence—and thus to time itself.

From this perspective, time is born anew with every conscious act. It is not the backdrop of existence but a product of interaction. Reality is not a film already made but a story continuously written by the interplay of matter, energy, and mind.

This idea blurs the boundary between physics and philosophy, between the objective and the subjective. It suggests that time’s creation is not merely a cosmic event but a living process—a dialogue between universe and observer.

The Eternal Now

If time is an illusion, what remains is the eternal present. Mystical traditions across cultures have long intuited this truth. Buddhism speaks of the “suchness” of each moment, Christianity of the “everlasting now” of divine being. Physics, too, seems to converge on the notion that all events coexist in a timeless whole.

In this view, the past has not vanished, nor has the future yet to come. They exist as parts of the same cosmic tapestry. What we call “now” is simply the slice of reality our consciousness experiences.

To live in awareness of the eternal present is not to deny time, but to transcend it—to see the unfolding universe as a single, unified creation. In doing so, we glimpse what Einstein once called “the illusion of time’s passage,” and yet also the profound beauty of its appearance.

Beyond the Horizon of Time

The question “Does time exist?” may never yield a final answer. It sits at the intersection of science and metaphysics, of mathematics and meaning. Physics may describe how time behaves, but it cannot explain why we experience it as we do. Consciousness gives time its rhythm, just as time gives consciousness its continuity.

Perhaps time is both real and unreal—a dual aspect of reality that depends on perspective. From the cosmic viewpoint, time is geometry. From the human viewpoint, it is life itself. One does not cancel the other; they complete the picture together.

As we probe deeper into the universe—through quantum gravity, cosmology, and consciousness studies—we may discover that time is not a fundamental property of the cosmos, but an emergent phenomenon arising from its interconnectedness. Or we may find that time is woven into the very logic of reality, inseparable from existence itself.

Either way, time remains the most intimate mystery. It is the measure of our mortality and the key to eternity. It defines our beginnings and endings, yet may itself have neither.

The Mystery That Lives Within Us

In the end, asking whether time exists is like asking whether the melody exists apart from the notes that compose it. Perhaps time is the music of the universe—the harmony produced by the dance of energy and matter. Without that rhythm, there would be no change, no memory, no being.

We are creatures born of time, shaped by its flow, and yet capable of questioning its reality. That very act of wonder places us at the heart of the mystery.

Does time exist? Perhaps not as we think. But its illusion—if illusion it is—is the most profound and beautiful ever conceived. For in that illusion, stars are born, lives unfold, and the universe itself becomes aware.

And so, even if time is only a dream, it is a dream through which the cosmos learns to see itself—a dream we call existence.