For as long as humanity has gazed at the night sky, we have wondered whether we are alone. The stars have whispered ancient questions into the human soul—questions about origins, purpose, and destiny. Yet for most of history, the idea of another Earth, another home among the stars, was confined to myth and imagination. The heavens were eternal and unchanging, and our world seemed singular in its beauty and life. But that illusion shattered in the late 20th century. Today, we know that planets are not rare jewels scattered sparingly across the galaxy—they are everywhere.

Astronomers have confirmed more than five thousand exoplanets orbiting distant stars, and thousands more candidates await verification. These worlds range from gas giants larger than Jupiter to rocky planets smaller than Earth. Some orbit so close to their suns that their skies blaze with molten clouds; others wander alone, cast adrift in the cold void. Yet amid this cosmic menagerie, a few stand out as extraordinary—worlds that could, under the right conditions, cradle life.

The search for an “Earth 2.0” is no longer science fiction; it is one of the most profound scientific quests of our time. Each new discovery brings us closer to answering a question older than civilization itself: Are we a cosmic accident, or is life a universal phenomenon?

A Universe of Worlds

The modern age of exoplanet discovery began in 1995, when Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz detected a planet orbiting the star 51 Pegasi. This world, named 51 Pegasi b, was a “hot Jupiter”—a gas giant orbiting perilously close to its star, completing a revolution in just four days. Its existence stunned astronomers. No one had expected such a planet to exist, yet its discovery proved that planetary systems could be far more diverse than our own.

Since then, new techniques have revolutionized the hunt. The transit method, which measures tiny dips in a star’s brightness as a planet passes in front of it, has been particularly fruitful. NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, launched in 2009, surveyed over 150,000 stars and revealed that planets outnumber stars in the Milky Way. The radial velocity method, detecting the subtle wobble of a star caused by an orbiting planet’s gravity, has confirmed many of Kepler’s candidates.

With the advent of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and next-generation observatories, astronomers can now analyze exoplanet atmospheres, searching for the chemical fingerprints of life—oxygen, methane, water vapor, and carbon dioxide. Each discovery deepens our sense of cosmic wonder. Among the countless worlds in the galaxy, some appear hauntingly familiar. They orbit in the “habitable zone”—the narrow band around a star where liquid water could exist. These are the planets we call “potential Earths.”

What Makes a Planet Habitable?

To understand what defines an “Earth-like” world, we must first understand what makes Earth so special. Our planet orbits at just the right distance from the Sun—not too hot, not too cold. This region, often called the “Goldilocks zone,” allows water to remain liquid on the surface, a fundamental requirement for life as we know it.

But distance alone does not make a planet habitable. The composition of its atmosphere, its size, and the nature of its star all play critical roles. A planet too small may lose its atmosphere to space; one too large may trap heat beneath crushing clouds, as Venus does. The star must be stable, not prone to violent flares that would strip away life’s delicate chemistry. And the planet must have essential ingredients—carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and trace minerals—that can form the complex molecules of biology.

A magnetic field helps protect the atmosphere from stellar winds, while plate tectonics recycle nutrients and regulate the climate. These factors combine to create a delicate balance. Finding another world where they all align is like discovering a single grain of sand on an infinite beach that mirrors our own. Yet we have begun to find hints that such grains do exist.

Kepler-452b: The First “Super-Earth” Twin

In 2015, NASA’s Kepler mission announced the discovery of Kepler-452b, a planet that instantly captured the world’s imagination. Orbiting a Sun-like star about 1,400 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus, it was hailed as the most Earth-like exoplanet yet found. Its star, Kepler-452, is only slightly older and hotter than our Sun, and the planet itself lies squarely in the habitable zone.

Kepler-452b is about 60 percent larger than Earth and likely has a rocky composition. Its orbital period—385 days—is strikingly similar to Earth’s year. Scientists estimate that its gravity would be nearly twice as strong as ours, enough to make walking there a slow, weighted endeavor. While no direct evidence of water or an atmosphere has been detected, models suggest it could have both.

Some have nicknamed it “Earth’s older cousin.” If life exists there, it might have evolved on a world a billion years ahead of our own in age—a haunting thought that invites both awe and humility. Yet Kepler-452b also serves as a reminder of how fragile habitability can be. As its star brightens over time, the planet may now be entering a runaway greenhouse phase, echoing what might one day happen to Earth itself.

The TRAPPIST-1 System: A Family of Worlds

If Kepler-452b represents an older sibling to Earth, then the TRAPPIST-1 system is an entire family of potential Earths. In 2017, astronomers announced that the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1, located about 40 light-years away, hosts seven Earth-sized planets—all within a region smaller than Mercury’s orbit around the Sun.

Three of these planets—TRAPPIST-1e, f, and g—lie within the star’s habitable zone, where liquid water might exist. Because TRAPPIST-1 is a dim red dwarf, its planets orbit much closer than Earth does to the Sun. A “year” on these worlds lasts only a few days, yet they receive similar amounts of energy as Earth does.

What makes the TRAPPIST-1 system particularly intriguing is its resemblance to a miniature solar system—a scaled-down version of our own. The planets likely formed together and interact gravitationally in a delicate resonance, keeping their orbits stable. JWST has already begun analyzing their atmospheres, searching for signs of water and perhaps even biosignatures.

The proximity of the system makes it an ideal target for future exploration. If any of these worlds harbor oceans or atmospheres, they could be prime candidates for life. TRAPPIST-1e, in particular, stands out: it is slightly smaller than Earth, likely rocky, and may possess a climate not unlike our own.

Proxima Centauri b: Our Nearest Neighbor

The dream of finding another Earth became even more tangible in 2016, when astronomers discovered a planet orbiting Proxima Centauri—the closest star to the Sun, just 4.24 light-years away. This world, Proxima Centauri b, orbits within its star’s habitable zone and is roughly 1.3 times the mass of Earth.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf, cooler and dimmer than the Sun. Its planet must orbit very close—just 0.05 astronomical units (about one-twentieth the distance between Earth and the Sun)—to receive enough warmth. As a result, it completes one orbit every 11 days.

The proximity of its star poses challenges. Red dwarfs are known for powerful stellar flares, which could strip away an atmosphere and irradiate the surface. Yet if Proxima b possesses a strong magnetic field or a dense atmosphere, it might still protect itself from these assaults. Some models even suggest the possibility of a temperate ocean world.

Because of its nearness, Proxima Centauri b may be the first exoplanet we can study in detail—and perhaps one day visit through robotic probes. Missions like Breakthrough Starshot envision sending miniature spacecraft propelled by light sails to reach the system within a human lifetime. The possibility that our nearest neighbor could also be habitable is both scientifically thrilling and emotionally profound.

Kepler-186f: A New Dawn in Cygnus

Among the early triumphs of the Kepler mission was Kepler-186f, discovered in 2014. It was the first Earth-sized planet confirmed to orbit within the habitable zone of another star. Located about 500 light-years away, it circles a red dwarf smaller and cooler than the Sun, completing an orbit every 130 days.

Kepler-186f receives about one-third of the sunlight Earth does—roughly equivalent to what Mars receives—but this could still allow for liquid water under the right atmospheric conditions. Its discovery was revolutionary because it proved that small, rocky planets in habitable zones are not rare.

The system’s other planets orbit too close for life as we know it, but Kepler-186f sits in a sweet spot, where the balance between heat and radiation might allow for a stable climate. Because its star is much dimmer than the Sun, any life there would see a perpetual orange-red twilight rather than blue skies. Plants, if they existed, might evolve dark pigments to absorb the weak starlight.

Kepler-186f remains beyond our technological reach for direct observation, yet it stands as a symbol of possibility—a world that could remind us of our own, orbiting quietly in a distant constellation.

LHS 1140b: A Super-Earth with Secrets

Discovered in 2017, LHS 1140b orbits a small red dwarf 40 light-years away in the constellation Cetus. It quickly gained attention as one of the best candidates for habitability. Slightly larger and more massive than Earth, it is classified as a “super-Earth,” likely with a dense, rocky composition.

LHS 1140b lies comfortably in its star’s habitable zone, receiving about half the sunlight Earth does. Unlike many red dwarf planets, it may have retained its atmosphere, possibly rich in water vapor or carbon dioxide. Scientists speculate that it could host a deep ocean beneath a protective layer of clouds.

The planet’s star is relatively quiet, meaning it emits fewer harmful flares than most red dwarfs. This stability increases the chances of life-friendly conditions. With the James Webb Space Telescope now studying its light spectrum, astronomers hope to determine whether the planet has water or even biosignatures.

If confirmed, LHS 1140b could become one of the most promising Earth analogues ever found—a world that demonstrates that even around dim stars, life may find a foothold.

TOI 700 d and e: New Hope from TESS

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched in 2018, continues Kepler’s legacy by scanning nearly the entire sky. One of its most exciting discoveries came in the form of TOI 700 d, a rocky planet about 100 light-years away. In 2023, another planet in the same system—TOI 700 e—was found, making this star one of the most intriguing for habitability studies.

TOI 700 is a quiet red dwarf, and both planets lie near or within its habitable zone. TOI 700 d is about 20 percent larger than Earth and completes an orbit every 37 days. Climate models suggest that it could support stable surface water if its atmosphere resembles Earth’s or Venus’s in density.

The newly found TOI 700 e is even closer in size to Earth and may also possess moderate temperatures suitable for liquid water. Together, they offer scientists a rare opportunity to study two potentially habitable worlds orbiting the same star—a cosmic laboratory for understanding how conditions for life arise and vary.

K2-18b: A Possible Water World

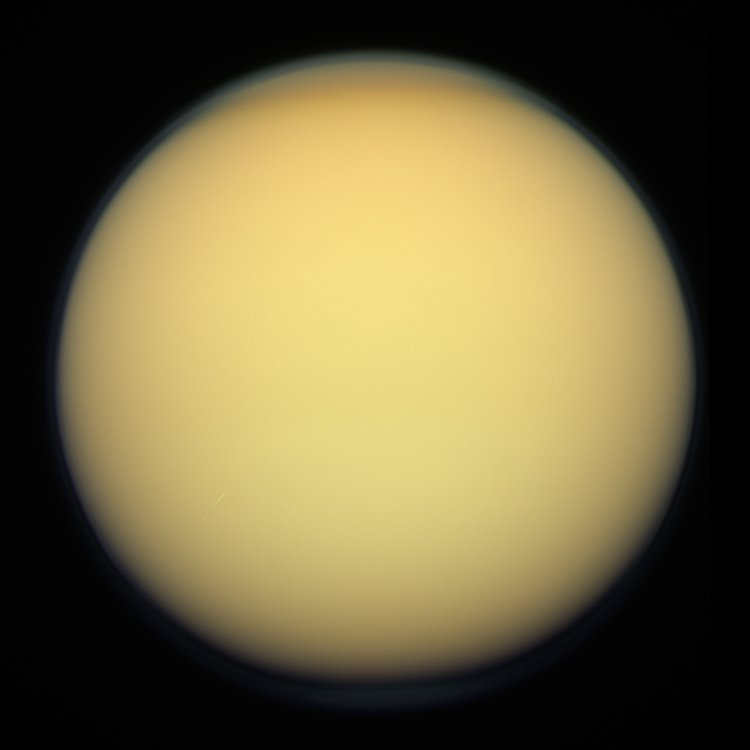

In 2019, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope detected water vapor in the atmosphere of K2-18b, a super-Earth located 124 light-years away. This marked the first time water—a key ingredient for life—was found on a planet within its star’s habitable zone.

K2-18b is roughly eight times Earth’s mass and about twice its size, suggesting a thick atmosphere. It orbits a red dwarf and receives about the same amount of light energy as Earth does from the Sun. Scientists believe it might be a “hycean” planet—a world covered by a global ocean beneath a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

Recent observations with JWST have hinted at the presence of carbon-bearing molecules, possibly even dimethyl sulfide, which on Earth is produced only by living organisms. While these results remain tentative, they represent one of the most tantalizing signs yet that a distant world might harbor life.

K2-18b challenges our traditional notions of habitability. It reminds us that “Earth-like” may not mean identical to Earth; life may thrive in environments we have yet to imagine.

Gliese 667Cc and Beyond

Not all habitable worlds need to orbit Sun-like stars. Gliese 667Cc, about 23 light-years away, circles a red dwarf in a triple-star system. It is about four times Earth’s mass and orbits within the star’s habitable zone, where conditions might permit liquid water.

The system’s complex dynamics mean that Gliese 667Cc experiences light from multiple suns, each contributing to its warmth and illumination. If the planet possesses an atmosphere, its skies might glow in hues of orange and crimson, casting surreal landscapes beneath shifting starlight.

Dozens of other candidates join this growing list: Ross 128b, Teegarden’s Star b, and Wolf 1069b—all nearby, all potentially temperate. Each one tells a slightly different story about how planets evolve and where life might take root.

The Role of the James Webb Space Telescope

With the deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope in 2021, humanity gained an instrument capable of peering into the atmospheres of distant worlds with unprecedented precision. By analyzing starlight filtered through a planet’s atmosphere during transit, JWST can detect molecules such as water, methane, ozone, and carbon dioxide—biosignatures that hint at life.

Already, JWST has begun transforming exoplanet science. Its observations of systems like TRAPPIST-1 and K2-18b are revealing not only what these planets are made of but also how diverse habitable worlds can be. In the coming years, it will allow astronomers to compare entire planetary atmospheres, uncovering patterns that may point toward biological processes.

The dream of detecting life beyond Earth may not remain a dream for long. The technology now exists to glimpse alien skies—to study sunsets on other worlds and perhaps even detect the chemical breath of living organisms.

The Fragility of Habitability

As we discover more potential Earths, we also confront the fragility of our own. Many exoplanets once considered promising have turned out to be too hot, too cold, or too irradiated. Even small variations in distance or atmospheric composition can make the difference between a paradise and a wasteland.

These discoveries underscore how finely balanced Earth’s conditions truly are. Our planet’s atmosphere shields us from radiation, moderates temperature, and provides breathable air. Our magnetic field protects against solar winds. Our Moon stabilizes our tilt, giving us predictable seasons. Each of these factors contributes to an improbable harmony.

In seeking other habitable worlds, we are not merely looking for escape routes; we are learning what makes our own world unique—and why it must be protected.

The Meaning of Earth 2.0

When scientists speak of finding “Earth 2.0,” they do not necessarily mean a perfect twin. Instead, the term represents a symbol—a world where life could exist, where conditions echo our own enough to allow familiar chemistry to unfold. Such planets might not have blue oceans or green continents; they could be shrouded in mist, covered in ice, or enveloped in red light. Yet beneath those alien skies, the same universal laws of physics and chemistry might give rise to something that breathes, moves, and thinks.

Finding another Earth-like planet would not only transform science but also philosophy and religion. It would redefine our sense of place in the cosmos. For centuries, humanity believed itself to be at the center of creation. Each new discovery—heliocentrism, evolution, the vastness of the universe—has humbled us further. The detection of life beyond Earth would complete that journey, showing that we are part of a larger cosmic story.

The Future of Exploration

The search for Earth 2.0 is accelerating. New missions like NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory and the European Space Agency’s PLATO and Ariel telescopes will scan nearby stars with unprecedented precision. Ground-based observatories such as the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile will directly image exoplanets, capturing actual pictures of distant worlds.

Within decades, we may identify a true twin of Earth—a planet with clouds, continents, and oceans seen shimmering in reflected light. Spectroscopy could reveal the chemical imbalance of a living atmosphere, the signature of photosynthesis, or even hints of civilization.

Some dream of sending probes across interstellar space. The distances are immense, but concepts like laser-propelled sails and autonomous nanocraft offer hope that humanity could one day glimpse these worlds firsthand. To stand on an alien shore and see two suns rise above an unfamiliar horizon would be to witness the next chapter of human destiny.

A Mirror Among the Stars

In the search for other Earths, we are ultimately searching for ourselves. Each discovery reflects a different possibility of what life might be, and what we might become. The universe, once thought empty and indifferent, now appears teeming with potential.

Perhaps among the billions of stars, there is a world where oceans sparkle beneath alien constellations, where creatures gaze up at their sky and wonder, as we do, if they are alone. Perhaps, someday, our signals will cross—their light reaching us even as ours reaches them—and two civilizations will realize they have been looking at each other all along.

Earth 2.0 may still be distant, but its discovery feels inevitable. The cosmos is vast enough, ancient enough, and rich enough for countless worlds to bloom. When we finally find one, it will not diminish Earth—it will elevate it. For in recognizing another cradle of life, we will understand more deeply the preciousness of our own.

The stars will no longer be silent witnesses to our curiosity; they will be gateways to kinship. And the phrase “Earth-like” will no longer mean something distant and abstract—it will mean that the universe, in all its grandeur, is capable of repeating the miracle of home.