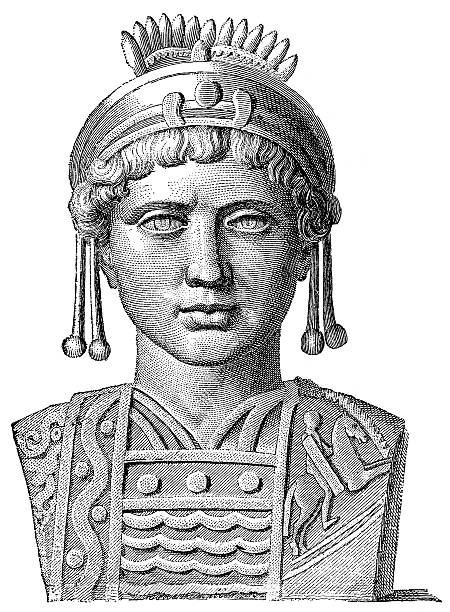

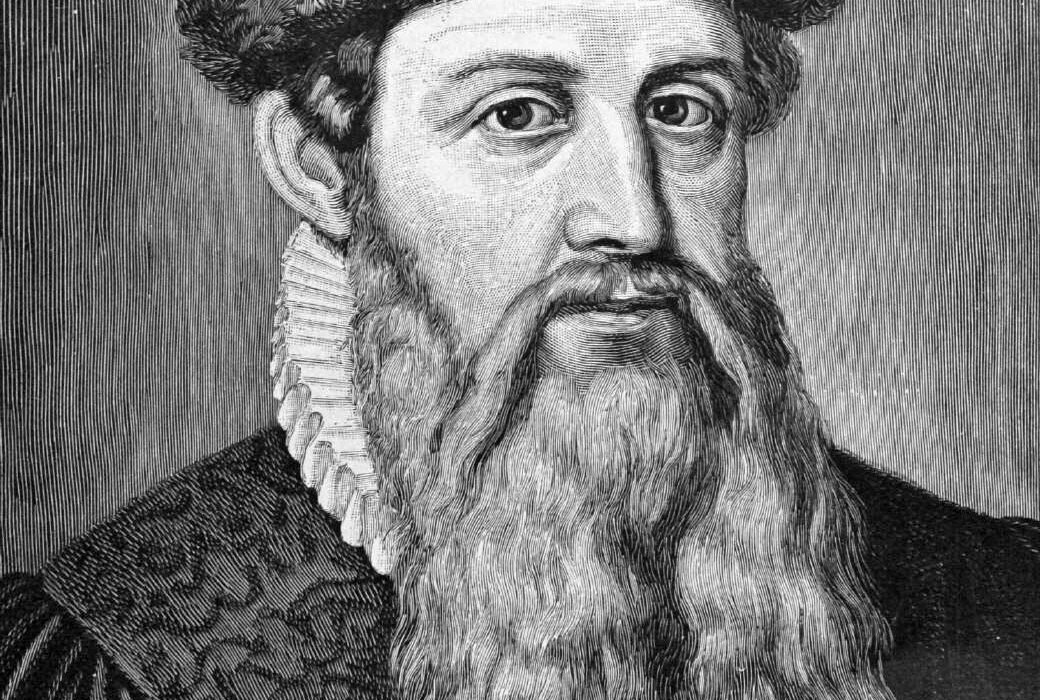

Francisco Pizarro (c. 1475–1541) was a Spanish conquistador known for leading the expedition that ultimately conquered the Inca Empire in South America. Born in Trujillo, Spain, Pizarro embarked on several voyages to the New World, driven by the lure of wealth and adventure. In 1532, he led a small force into the heart of the Inca Empire, located in present-day Peru, and captured the Inca ruler, Atahualpa. Despite being vastly outnumbered, Pizarro’s strategic cunning, combined with superior weaponry and alliances with local tribes, allowed him to defeat the Incas. His conquest opened vast territories to Spanish control and significantly contributed to Spain’s wealth during the colonial period. However, Pizarro’s legacy is controversial, marked by both his role in expanding European influence and the devastation of indigenous cultures. He was assassinated in Lima in 1541 by rivals, leaving a complex and debated historical legacy.

Early Life and Background

Francisco Pizarro was born around 1476 in Trujillo, Spain, into a family of modest means. His father, Gonzalo Pizarro, was a colonel of infantry, but his mother, Francisca González, was of humble origin, making Francisco an illegitimate child. Little is known about his early life, but it is generally believed that he grew up in relative poverty and received no formal education. The harsh conditions of his upbringing in the rugged region of Extremadura likely instilled in him the resilience and determination that would later define his career as a conquistador.

As a young man, Pizarro sought adventure and fortune in the New World, inspired by the tales of exploration and conquest that had begun to circulate in Spain following Christopher Columbus’s voyages. By 1502, he had joined an expedition to Hispaniola, the first European colony in the Americas, where he served as a soldier. This was the beginning of a long and tumultuous journey that would eventually lead him to the shores of South America and into the annals of history as one of its most controversial figures.

Pizarro’s early years in the New World were spent honing his skills as a soldier and explorer. He participated in various expeditions, including the conquest of Panama, where he served under the command of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European to see the Pacific Ocean from the New World. It was during this time that Pizarro first heard rumors of a wealthy empire to the south, which would eventually lead him to the fabled land of the Incas.

Pizarro’s determination to pursue his ambitions was matched by his ruthlessness and cunning. Unlike other conquistadors who sought royal approval before embarking on their expeditions, Pizarro often took matters into his own hands. His ability to navigate the treacherous waters of colonial politics, coupled with his fierce determination, set the stage for his later conquests. These traits would prove essential as he set his sights on the riches of the Inca Empire, a civilization that was, at the time, one of the most advanced in the world.

The First Expeditions to South America

Pizarro’s first significant expedition to South America began in 1524 when he partnered with Diego de Almagro and Hernando de Luque. The trio aimed to explore the lands south of Panama, where they believed vast wealth awaited. Their initial expedition, however, was fraught with difficulties. They faced hostile terrain, severe weather conditions, and resistance from indigenous populations. The journey proved to be more challenging than they had anticipated, and the expedition was forced to return to Panama with little to show for their efforts.

Undeterred, Pizarro organized a second expedition in 1526. This time, he ventured further south, reaching the northern coast of present-day Peru. Here, he encountered the first signs of the Inca Empire, a civilization that boasted immense wealth and a sophisticated social structure. Despite the hardships of the journey, including skirmishes with hostile tribes and the harsh Andean environment, Pizarro’s resolve only grew stronger. The sight of Inca gold and the stories of a vast empire fueled his ambition to conquer these lands.

The second expedition also faced significant challenges, including the loss of several men to disease and the harsh conditions of the coastal desert. However, Pizarro’s perseverance paid off when he reached the island of Gallo, where he famously drew a line in the sand and challenged his men to cross it if they were willing to follow him to the riches of Peru. Although many chose to return to Panama, thirteen men, known as “The Famous Thirteen,” stayed with Pizarro, committing to the pursuit of the Inca Empire.

Upon returning to Panama, Pizarro sought support from the Spanish crown to legitimize his expedition and secure the resources needed for a full-scale conquest. He traveled to Spain in 1528, where he met with King Charles I and Queen Isabella. Impressed by Pizarro’s determination and the potential wealth of the Inca Empire, the crown granted him the authority to lead the conquest of Peru. This royal backing was a turning point in Pizarro’s career, providing him with the legitimacy and resources necessary to embark on what would become one of the most significant conquests in the history of the Americas.

The Conquest of the Inca Empire

In 1531, Francisco Pizarro set sail from Panama with a small force of approximately 180 men, including his brothers, to begin the conquest of the Inca Empire. The journey southward was perilous, but Pizarro’s previous expeditions had prepared him for the challenges ahead. By the time he reached the Inca heartland, the empire was embroiled in a civil war between two brothers, Atahualpa and Huáscar, who were vying for control of the throne. Pizarro quickly recognized the opportunity to exploit this internal conflict to his advantage.

Pizarro and his men arrived in the town of Cajamarca in November 1532, where they arranged a meeting with Atahualpa, who had emerged as the victor in the civil war. The meeting was a trap; Pizarro and his men ambushed the Inca forces, capturing Atahualpa and massacring thousands of his warriors. Despite being vastly outnumbered, the Spanish soldiers, armed with superior weaponry and aided by their horses, easily overwhelmed the Inca forces. The capture of Atahualpa marked a decisive moment in the conquest of the Inca Empire.

Atahualpa, now a prisoner, attempted to ransom himself by offering Pizarro a room filled with gold and silver. Pizarro agreed to the ransom, and over the next few months, vast amounts of treasure were delivered to the Spanish. However, once the ransom was paid, Pizarro reneged on his promise to release Atahualpa. Fearing that the Inca emperor might rally his people against the Spanish, Pizarro ordered his execution in 1533, an act that effectively decapitated the leadership of the Inca Empire and paved the way for the Spanish conquest.

Following Atahualpa’s death, Pizarro marched on the Inca capital of Cusco, which fell to the Spanish in 1533. The conquest of Cusco symbolized the collapse of the Inca Empire, but Pizarro’s work was far from over. Resistance from Inca loyalists continued for years, leading to prolonged military campaigns. Despite these challenges, Pizarro established a new capital at Lima in 1535, which became the center of Spanish colonial power in South America. Lima, known as “The City of Kings,” was strategically located on the coast, allowing for better communication and trade with Spain.

The conquest of the Inca Empire is one of the most significant events in the history of the Americas. It marked the beginning of Spanish dominance in South America and the eventual establishment of the Viceroyalty of Peru. However, it also brought about the collapse of one of the most advanced civilizations in the world, leading to centuries of exploitation and oppression of the indigenous populations. Pizarro’s role in this conquest has made him a controversial figure, celebrated for his achievements by some and condemned for his brutal tactics by others.

Governorship and Internal Conflicts

Following the successful conquest of the Inca Empire, Francisco Pizarro was appointed governor of the newly established Spanish territories in Peru. His governorship, however, was marked by internal conflicts and power struggles, particularly with his former ally, Diego de Almagro. The rivalry between Pizarro and Almagro stemmed from disputes over the division of the spoils of conquest and the boundaries of their respective territories.

In 1535, Pizarro founded the city of Lima, which he intended to be the administrative and political center of Spanish rule in South America. The city’s strategic location on the Pacific coast allowed for easier communication with Spain and facilitated the exploitation of the region’s resources. Lima quickly grew in importance, becoming the most significant city in the Spanish colonies in South America. However, Pizarro’s governorship was not without challenges. The initial years were marked by ongoing conflicts with remaining Inca forces and dissent among the Spanish settlers.

The most significant challenge to Pizarro’s authority came from Diego de Almagro, who believed he had been unfairly treated in the distribution of land and power. In 1537, Almagro seized Cusco, the former Inca capital, and declared himself its ruler. This act of defiance led to a civil war between Pizarro’s forces and those loyal to Almagro. The conflict culminated in the Battle of Las Salinas in 1538, where Pizarro’s forces emerged victorious. Almagro was captured and executed, effectively ending the civil war and solidifying Pizarro’s control over the region.

Despite his victory, Pizarro’s governorship continued to be plagued by unrest. The execution of Almagro did little to quell the tensions among the Spanish settlers, many of whom were dissatisfied with their share of the spoils. Moreover, Pizarro’s autocratic style of governance alienated many of his former allies, leading to growing discontent. This discontent eventually culminated in a conspiracy against Pizarro, led by the supporters of Almagro’s son, Diego de Almagro II.

In 1541, a group of conspirators, seeking revenge for Almagro’s execution, attacked Pizarro in his palace in Lima. Despite his advanced age, Pizarro fought bravely but was ultimately overpowered and killed. His death marked the end of his rule and the beginning of a period of instability in the Spanish territories in South America. The assassination of Francisco Pizarro on June 26, 1541, marked a dramatic end to his tumultuous rule in the Spanish territories of South America. The attack was orchestrated by supporters of Diego de Almagro II, the son of Pizarro’s former rival, Diego de Almagro. Almagro II sought to avenge his father’s death and reclaim what he believed was his rightful share of the spoils of conquest.

The conspirators, led by Almagro II and his allies, stormed Pizarro’s residence in Lima, overpowered his guards, and brutally assassinated him. Pizarro’s death was a violent culmination of the deep-seated rivalries and power struggles that had plagued his governorship. The conspirators, driven by personal vendettas and dissatisfaction with Pizarro’s rule, sought to restore the balance of power that had been disrupted by his conquests and governance.

In the aftermath of Pizarro’s assassination, the Spanish authorities in Peru faced a period of significant instability. The power vacuum left by his death led to further conflicts among the Spanish settlers, as various factions vied for control of the region. The political turmoil also attracted the attention of Spanish officials in Spain, who were concerned about the stability of their colonial holdings.

The Spanish Crown intervened to restore order in the region. In 1542, the Crown appointed a new governor, Blasco Núñez Vela, to replace Pizarro. Núñez Vela’s arrival marked the beginning of a series of reforms aimed at addressing the grievances of the settlers and restoring stability to the Spanish colonies. These reforms included efforts to resolve the disputes over land and wealth that had fueled the conflicts between Pizarro and his rivals.

Despite the efforts to stabilize the region, the legacy of Pizarro’s rule continued to influence the politics and society of colonial Peru. His conquests had laid the foundation for Spanish control over one of the richest regions in the New World, but they also set the stage for a complex and often violent struggle for power among the Spanish settlers.

Pizarro’s assassination and the subsequent power struggles highlighted the inherent instability and challenges of colonial governance. The conflicts that followed his death were a testament to the difficulties of managing a vast and diverse empire, especially one built on the exploitation of indigenous populations and the pursuit of personal ambitions.

Despite the controversies surrounding his rule, Francisco Pizarro’s impact on the history of South America is undeniable. His conquests reshaped the continent’s political and cultural landscape, leading to the establishment of Spanish colonial rule that would last for centuries. Pizarro’s legacy remains a subject of debate, with some viewing him as a brilliant and ambitious conqueror and others as a ruthless opportunist. His life and career continue to be studied and discussed as part of the broader history of European exploration and colonization in the Americas.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Francisco Pizarro’s legacy is a complex and contested subject in the annals of history. As the primary architect of the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, Pizarro is often remembered for his role in one of the most dramatic and consequential events of European colonialism in the Americas. His achievements, including the capture of the Inca emperor Atahualpa and the conquest of the vast Inca Empire, had profound and lasting effects on the history of South America.

On one hand, Pizarro is celebrated for his strategic acumen, leadership, and ability to capitalize on the internal divisions within the Inca Empire. His conquests brought enormous wealth to Spain and laid the groundwork for Spanish dominance in South America. The vast quantities of gold and silver extracted from the region significantly contributed to Spain’s economic power in the 16th century, bolstering its position as a global superpower. Pizarro’s establishment of Lima as the capital of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru was a key move that ensured Spanish control over the region and facilitated further colonization and exploitation.

On the other hand, Pizarro’s legacy is marred by the violence and brutality that characterized his conquests. The methods he employed, including ambushes, massacres, and the exploitation of internal conflicts, contributed to the downfall of one of the most sophisticated and advanced civilizations in the world. The impact of Pizarro’s actions on the indigenous populations of South America was devastating, leading to widespread suffering, displacement, and cultural disruption. The Spanish conquest led to the imposition of foreign rule, the spread of diseases that decimated indigenous populations, and the beginning of a colonial era marked by exploitation and oppression.

Historical assessments of Pizarro also reflect the broader debates about European colonization and its consequences. Some historians view him as a product of his time, a figure whose actions were driven by the norms and values of 16th-century Spain, where exploration and conquest were seen as means to achieve glory and wealth. Others critique him as an embodiment of the destructive impact of European imperialism on indigenous cultures and societies.

Pizarro’s life and career have been the subject of numerous historical studies, biographies, and interpretations. His role in the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire continues to be a topic of interest for scholars and educators, who examine his achievements and failures within the broader context of colonial history. His legacy is a reminder of the complex interplay between ambition, power, and human suffering that defined the era of European exploration and conquest.

In contemporary discussions, Pizarro’s legacy is often re-evaluated through the lens of indigenous perspectives and postcolonial scholarship. This approach seeks to highlight the experiences and voices of the indigenous peoples affected by the Spanish conquest, offering a more nuanced and critical view of Pizarro’s impact on South America. By examining his legacy from multiple angles, historians and scholars aim to provide a more comprehensive understanding of his place in history and the enduring consequences of his actions.

Final Years and Death

The final years of Francisco Pizarro’s life were marked by conflict, instability, and the consequences of his own actions. After his successful conquest of the Inca Empire and the establishment of Lima as the capital of Spanish Peru, Pizarro faced numerous challenges that would ultimately lead to his downfall.

In the years following the conquest, Pizarro continued to consolidate his control over the newly acquired territories. However, his governance was plagued by internal dissent and power struggles. The tensions between Pizarro and his former allies, particularly with Diego de Almagro, had far-reaching consequences. The disputes over land and resources led to a bitter rivalry that escalated into a civil war among the Spanish settlers.

The conflict between Pizarro and Almagro’s supporters came to a head in 1538 at the Battle of Las Salinas. Pizarro’s forces emerged victorious, leading to the capture and execution of Diego de Almagro. This victory solidified Pizarro’s control over the region but also intensified the rivalries and discontent among the Spanish colonists. The power struggles continued, contributing to a volatile political environment in the Spanish territories of South America.

Pizarro’s leadership was further challenged by his own increasingly autocratic style of governance. His decisions and actions alienated many of his former allies and created factions among the Spanish settlers. The dissatisfaction with his rule grew, and unrest became a common feature of his administration. The instability and conflict ultimately culminated in a conspiracy against Pizarro.

In 1541, a group of conspirators, including supporters of Diego de Almagro II, launched a coordinated attack on Pizarro’s residence in Lima. The assault was a brutal and violent event that resulted in Pizarro’s assassination. Despite his efforts to defend himself, Pizarro was overpowered and killed by the conspirators seeking revenge for the death of Diego de Almagro and the ongoing grievances against his rule.

Pizarro’s death marked the end of an era of Spanish dominance in Peru and ushered in a period of further instability and conflict. The assassination created a power vacuum that required intervention from the Spanish Crown. The subsequent arrival of a new governor, Blasco Núñez Vela, aimed to restore order and address the issues that had plagued Pizarro’s administration.

Despite the turbulent final years of his life, Francisco Pizarro’s impact on the history of South America remained significant. His conquests reshaped the political and cultural landscape of the continent, leading to the establishment of Spanish colonial rule and the transformation of the Inca Empire into a Spanish colony. Pizarro’s legacy, however, is complex and often controversial, reflecting both the achievements and the consequences of his actions in the New World.

The study of Pizarro’s final years provides valuable insights into the challenges and conflicts of early colonial governance. It also highlights the broader themes of ambition, power, and the human cost of conquest that defined the era of European exploration and colonization. Pizarro’s life and career continue to be examined and debated, offering a multifaceted view of one of history’s most influential and contentious figures.