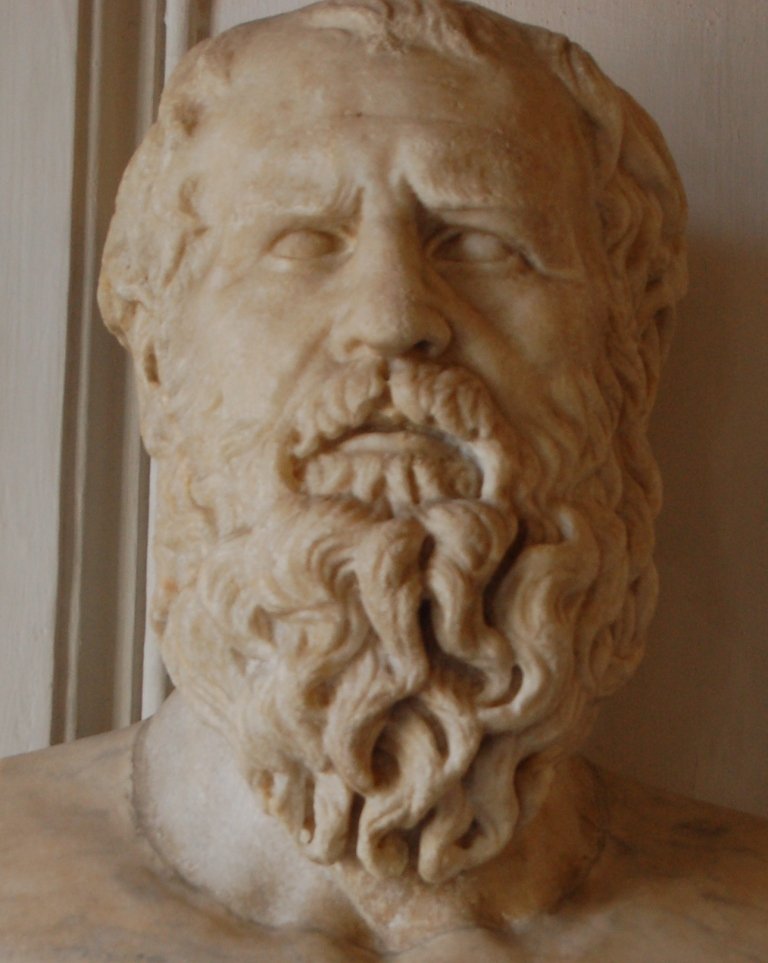

Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 535–475 BCE) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher known for his doctrine of change, encapsulated in the famous phrase, “You cannot step into the same river twice.” He believed that the fundamental nature of reality is constant flux, where everything is in a state of perpetual change. Heraclitus saw fire as the primary element symbolizing transformation, and he emphasized the unity of opposites, arguing that contradictions drive the world’s dynamic balance. Often called “The Obscure” for his cryptic and paradoxical style, Heraclitus challenged the conventional views of his time, rejecting both the notion of a static world and simplistic dualities. His ideas significantly influenced later philosophers, particularly the Stoics and even modern thinkers, as they explored the nature of reality, change, and the interconnectedness of opposites. Despite the fragmentary nature of his surviving work, Heraclitus remains a central figure in Western philosophy.

Early Life and Historical Context

Heraclitus of Ephesus, born around 535 BCE in the prosperous and culturally rich city of Ephesus in Ionia, stands as one of the most enigmatic and profound pre-Socratic philosophers. Ephesus, situated on the western coast of modern-day Turkey, was a significant center for trade, learning, and culture in ancient Greece. The city was home to the magnificent Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, symbolizing its affluence and importance.

Little is known about Heraclitus’ early life and personal background, and what we do know comes largely from later sources that reflect on his philosophy. Unlike many of his contemporaries who hailed from prominent aristocratic families, Heraclitus’ background is less well-documented. However, it is believed that he came from an aristocratic family himself, though he famously rejected political power in favor of intellectual pursuits. Tradition suggests that he was offered the position of Basileus (king or ruler) of Ephesus but turned it down to live a life of contemplation and solitude. This decision aligns with his disdain for the masses and his belief that true wisdom was not to be found in popular opinion but in deep reflection on the nature of the cosmos.

Heraclitus lived during a period of immense change in the Greek world. The 6th century BCE was marked by the rise of city-states (poleis), the establishment of democratic forms of government in some regions, and significant advancements in art, science, and philosophy. Ionian thinkers were pioneering natural philosophy, questioning the nature of existence, and seeking explanations for the cosmos that went beyond the traditional mythological narratives. Figures like Thales, Anaximander, and Pythagoras were exploring new ideas about the world, setting the stage for Heraclitus’ radical contributions to philosophy.

Heraclitus is often referred to as “the Obscure” or “the Dark” due to the cryptic and paradoxical nature of his writings. His work is characterized by brief, aphoristic statements that leave much room for interpretation. Unlike other pre-Socratic philosophers who wrote systematic treatises or poems, Heraclitus’ surviving fragments are more enigmatic, often challenging readers to delve into the deeper meaning behind his words. This style reflects his belief that true understanding requires active engagement and cannot be easily handed down in simple terms.

Heraclitus’ only known work, traditionally titled On Nature (though this title may be later speculation), is lost to history, with only about 130 fragments surviving, preserved mainly by later philosophers and writers such as Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. These fragments offer a glimpse into his profound and often perplexing thoughts on the nature of reality, the cosmos, and human existence.

While Heraclitus was critical of the masses and dismissed the common beliefs of his time, his philosophy was deeply concerned with the underlying principles of the universe. His most famous doctrine, the idea that “everything flows” or “everything changes” (panta rhei), reflects his belief in the constant flux and impermanence of all things. This concept would go on to influence not only later Greek philosophy but also many other schools of thought throughout history.

Heraclitus’ disdain for the common people was evident in his critiques of popular religion and his belief that most people failed to grasp the deeper truths of the cosmos. He famously criticized Homer, the great epic poet of Greece, and expressed contempt for the worship of deities like Dionysus and the mysteries surrounding such cults. For Heraclitus, the truth lay not in the stories of gods and heroes but in the rational order of the universe, which he called the Logos.

The Logos, a central concept in Heraclitus’ thought, refers to the rational structure of the cosmos, the underlying principle that governs all things. While the exact meaning of the term is debated, it can be understood as a kind of universal law or reason that holds the universe together, despite its constant state of flux. Heraclitus believed that this Logos was accessible to human reason, though few people truly understood it. His disdain for human ignorance and his belief in the superiority of intellectual contemplation over the beliefs of the masses set him apart from many of his contemporaries and contributed to his reputation as a solitary and somewhat misanthropic figure.

Heraclitus’ views were not widely accepted during his lifetime, and he was often misunderstood or dismissed by his peers. However, his influence on later philosophical thought cannot be overstated. His ideas about change, opposites, and the Logos would resonate with philosophers for centuries to come, influencing schools of thought such as Stoicism, and later, existentialism and modern physics.

Heraclitus’ Philosophical Ideas: The Logos and the Doctrine of Flux

At the heart of Heraclitus’ philosophy is the concept of the Logos, which can be translated as “reason,” “word,” or “principle.” For Heraclitus, the Logos represents the rational order of the cosmos, the fundamental law that governs all things, and the underlying unity behind the apparent chaos of the world. While many pre-Socratic philosophers sought to explain the world in terms of a single substance (such as water, air, or fire), Heraclitus took a different approach. He believed that the essence of the universe could not be reduced to a single material element, but rather, it was defined by constant change and transformation.

Heraclitus’ famous doctrine of panta rhei, or “everything flows,” encapsulates his belief that change is the only constant in the universe. He famously stated, “You cannot step into the same river twice,” illustrating the idea that the world is in a state of continuous flux, where nothing remains the same for even a moment. The river may appear the same, but the water is always flowing, always changing. For Heraclitus, this constant state of becoming is the fundamental nature of reality. Stability, in his view, is an illusion.

The Logos, in this context, represents the unifying principle that governs the process of change. While everything in the universe is in flux, the Logos ensures that this change occurs according to a rational order. Heraclitus believed that the Logos was accessible to human reason, and that understanding it was the key to grasping the true nature of the cosmos. However, he also lamented that most people failed to recognize or comprehend the Logos, instead being distracted by the sensory appearances of the world.

In Heraclitus’ view, the world is characterized by a dynamic interplay of opposites. He believed that all things come into being through a process of tension and conflict between opposing forces. For example, day and night, life and death, war and peace, all exist in a state of balance and interdependence. Heraclitus expressed this idea in the famous fragment, “War is the father of all things,” suggesting that conflict and struggle are essential to the creation and maintenance of the cosmos.

This emphasis on opposites is closely related to Heraclitus’ concept of the unity of contraries. He believed that opposites are not merely conflicting forces, but rather, they are fundamentally connected and necessary for each other’s existence. For example, without darkness, there would be no concept of light; without cold, there would be no heat. This unity of opposites is another manifestation of the Logos, the underlying principle that brings harmony and order to the apparent chaos of the world.

Heraclitus’ ideas about change and the Logos stand in stark contrast to the philosophy of Parmenides, a contemporary pre-Socratic philosopher who argued that change was an illusion and that reality was fundamentally unchanging. While Parmenides believed that the senses deceived us into thinking that the world was in a state of flux, Heraclitus embraced change as the very essence of existence. This philosophical tension between Heraclitus and Parmenides would later influence the development of Greek philosophy, particularly in the work of Plato and Aristotle.

Heraclitus’ doctrine of flux also has implications for his views on knowledge and wisdom. Since the world is constantly changing, he believed that knowledge must also be dynamic and adaptable. He criticized those who sought certainty and fixed truths, arguing that true wisdom lies in understanding the ever-changing nature of the cosmos. This perspective would later resonate with the philosophy of existentialism, which also emphasizes the fluid and uncertain nature of human existence.

Despite the importance of the Logos in Heraclitus’ thought, he remained deeply pessimistic about the ability of most people to grasp this fundamental truth. He criticized the masses for their ignorance and complacency, believing that they were too focused on the superficial aspects of the world to see the deeper reality beneath. Heraclitus famously declared, “The waking have one common world, but the sleeping turn aside each into a world of his own.” For him, most people lived in a state of metaphorical sleep, unaware of the Logos and the true nature of the universe.

Heraclitus on Opposites: The Unity of Contraries

A crucial aspect of Heraclitus’ philosophy is his focus on opposites and the concept of the unity of contraries. For Heraclitus, the world is not merely a collection of isolated events or things but is characterized by a dynamic tension between opposing forces. This interplay of opposites, far from being a source of disorder, is central to the harmony and structure of the cosmos.

Heraclitus expressed this idea through several famous fragments, one of which states, “War is the father of all things.” This statement, provocative as it is, encapsulates his belief that conflict and opposition are essential to creation and transformation. In Heraclitus’ view, all things come into being through strife. It is the tension between opposites that drives the process of becoming. Without conflict, there would be no movement, no change, and thus no life.

This concept of tension and opposition as creative forces is present throughout Heraclitus’ fragments. He famously remarked that “The way up and the way down are one and the same,” suggesting that opposites are not merely different from one another but are intimately connected, even identical in some sense. The process of becoming involves a continual movement between opposites, and it is through this movement that the world is sustained.

Heraclitus extended this idea to all aspects of life and the universe. For example, he saw health and disease, life and death, and waking and sleeping as interdependent states. One cannot exist without the other. In another fragment, he wrote, “The hidden harmony is better than the obvious,” indicating that while opposites may appear to be in conflict, there is a deeper unity that binds them together. This hidden harmony is the Logos—the rational order that governs the cosmos.

Heraclitus’ focus on opposites can be understood as a challenge to conventional thinking. In traditional Greek thought, opposites were often seen as mutually exclusive—light and darkness, good and evil, life and death were considered distinct and irreconcilable. However, Heraclitus viewed these dichotomies as artificial divisions imposed by human perception. He believed that reality is more complex and interconnected than it appears on the surface, and that true understanding requires seeing beyond the apparent contradictions to grasp the underlying unity.

This idea of the unity of opposites was revolutionary in Greek philosophy and had a profound influence on later thinkers. It challenged the conventional wisdom of the time, which often sought to categorize and separate different aspects of the world. Instead, Heraclitus proposed that opposites are not only connected but necessary for each other’s existence. This idea would later resonate with the Stoics, who saw the world as governed by a rational order that encompasses all things, including opposites.

One of the clearest examples of Heraclitus’ doctrine of opposites is found in his reflections on the nature of life and death. He saw life and death as part of the same process, rather than distinct or opposing states. In one fragment, he wrote, “The path of ascent and descent is one and the same,” suggesting that birth and death are two aspects of the same journey. This cyclical view of existence challenges the conventional notion of life as a linear progression from birth to death. For Heraclitus, life is a constant process of transformation, and death is not an end but a part of this ongoing flux.

Another striking example is his view on health and disease. Heraclitus observed that health exists only in relation to disease—without the experience of illness, we would have no concept of health. This interdependence of opposites underscores his belief that opposites are not in opposition to each other in a destructive sense, but rather in a productive one. It is through the tension between opposites that the world is created and sustained.

Heraclitus also applied this concept to ethics and human behavior. He believed that good and evil, like other opposites, are interconnected and that moral values are relative rather than absolute. This perspective can be seen in his statement, “Good and evil are one.” For Heraclitus, what is considered good or evil depends on context and perspective. Just as light and darkness are part of the same continuum, so too are good and evil part of the same reality. This relativistic view of morality was controversial in his time and remains a topic of debate among philosophers today.

Heraclitus’ focus on the unity of opposites extends to his views on human nature and knowledge. He believed that understanding comes from recognizing the interconnectedness of all things. In one fragment, he wrote, “Men do not understand how that which is at variance with itself agrees with itself. It is a harmony of opposites, like that of the bow and the lyre.” This metaphor of the bow and lyre illustrates how tension and opposition can produce harmony. Just as a bowstring must be taut to shoot an arrow, and the strings of a lyre must be tuned to create music, so too does the tension between opposites create the harmony of the cosmos.

Heraclitus’ emphasis on opposites also reveals his view of the human condition. He saw human beings as caught in the tension between opposing forces, both within themselves and in the world around them. For Heraclitus, wisdom comes from recognizing and embracing this tension, rather than seeking to escape it. He believed that most people are unaware of the deeper reality of the world and are trapped in their limited perspectives. True wisdom, for Heraclitus, lies in seeing beyond the superficial appearances of things to grasp the underlying unity of opposites.

Heraclitus’ Views on Knowledge and Wisdom

Heraclitus’ views on knowledge and wisdom reveal his deep skepticism about the capacity of most people to understand the true nature of reality. He believed that while knowledge is attainable, it requires a special kind of insight that goes beyond ordinary perception and conventional wisdom. Heraclitus often criticized those who relied on sensory experience and popular opinion, arguing that such approaches failed to grasp the deeper truths of the cosmos.

Central to Heraclitus’ philosophy is the idea that wisdom is not simply the accumulation of facts or information but a profound understanding of the underlying order of the universe—the Logos. For Heraclitus, true wisdom involves recognizing the constant flux and transformation of all things and seeing the unity of opposites that underpins the apparent chaos of the world. This kind of understanding requires a shift in perspective, one that moves beyond the superficial and engages with the deeper reality of the cosmos.

Heraclitus was critical of those who claimed to possess knowledge but lacked this deeper insight. In one famous fragment, he wrote, “Much learning does not teach understanding.” This statement reflects his belief that intellectual pursuits alone do not lead to wisdom. He was particularly critical of the traditional education system of his time, which emphasized rote learning and the memorization of facts. For Heraclitus, true knowledge comes not from the accumulation of information but from a deep engagement with the Logos and an understanding of the interconnectedness of all things.

Heraclitus’ disdain for conventional wisdom extended to the religious and moral beliefs of his contemporaries. He criticized the common religious practices of his time, which he saw as based on superstition and a misunderstanding of the divine. Heraclitus believed that the gods were not distant, anthropomorphic beings who intervened in human affairs, but rather expressions of the underlying order of the universe. In one fragment, he wrote, “The wise is one alone, unwilling and willing to be called by the name of Zeus.” This statement suggests that the divine is not a personal deity but a manifestation of the Logos, the rational principle that governs all things.

Heraclitus also rejected the moral absolutism that was common in Greek thought. He believed that ethical values are relative and that what is considered good or evil depends on context and perspective. This relativistic view of morality is closely tied to his doctrine of opposites. Just as light and darkness are part of the same continuum, so too are good and evil part of the same reality. Heraclitus saw moral distinctions as artificial constructs that fail to capture the complexity of the world.

In contrast to the popular religious and moral beliefs of his time, Heraclitus advocated for a kind of philosophical wisdom that seeks to understand the deeper truths of the cosmos. He believed that this wisdom was accessible to those who were willing to engage in deep reflection and contemplation. However, he also recognized that this kind of understanding was rare. In one fragment, he lamented, “Eyes and ears are poor witnesses for men if their souls do not understand.” This statement reflects his belief that most people are trapped in their limited perceptions and fail to grasp the deeper reality of the world.

Heraclitus’ emphasis on the importance of understanding the Logos is closely related to his views on the nature of the self. He believed that true knowledge requires self-knowledge and that understanding the Logos involves understanding one’s own nature. In one fragment, he wrote, “I searched myself.” This statement suggests that the path to wisdom begins with introspection and self-examination. For Heraclitus, the self is not a fixed entity but is in a constant state of flux, just like the rest of the cosmos. Understanding the self requires recognizing this dynamic nature and embracing the tension between opposites that defines human existence.

Heraclitus’ exploration of self-knowledge goes beyond mere introspection and touches on his broader philosophical principles. He believed that understanding oneself is intertwined with understanding the cosmos because both the individual and the universe are governed by the same underlying principle, the Logos. In this sense, self-knowledge is not just about personal awareness but about recognizing one’s place within the larger order of the universe. This reflects his view that human beings are part of the ongoing flux and transformation that characterizes all existence.

In his fragment “I searched myself,” Heraclitus suggests that wisdom begins with an inward journey. However, this search is not for a static, unchanging essence but for an understanding of one’s own dynamic nature. Just as the river is constantly changing, so too is the self. Heraclitus believed that the self is defined by its constant becoming, its perpetual movement between opposites. To know oneself, therefore, is to recognize this continual process of change and to embrace the tension and conflict that are inherent in existence.

Heraclitus’ views on knowledge and wisdom are closely tied to his belief in the unity of opposites. He saw the pursuit of wisdom as a process of coming to terms with the contradictions and tensions that define both the self and the world. This process involves seeing beyond the surface appearances of things to grasp the deeper reality that underlies them. For Heraclitus, true wisdom is about recognizing the interconnectedness of all things and understanding that opposites are not mutually exclusive but are part of the same reality.

This approach to wisdom is reflected in his critique of conventional knowledge. Heraclitus believed that most people are content with superficial understanding and fail to grasp the deeper truths of the cosmos. In one fragment, he wrote, “The many live as though they have a private understanding,” criticizing the tendency of people to create their own limited interpretations of the world, disconnected from the Logos. For Heraclitus, true knowledge requires moving beyond individual perspectives and aligning oneself with the rational order of the universe.

Heraclitus also emphasized the importance of constant questioning and inquiry in the pursuit of wisdom. He believed that wisdom is not a fixed state that one can achieve, but a continuous process of learning and adapting to the ever-changing nature of the world. In this sense, wisdom for Heraclitus is dynamic, just like the universe itself. It involves an ongoing engagement with the flux and transformation that characterize existence, rather than a search for unchanging truths.

Heraclitus’ views on knowledge and wisdom have had a lasting impact on the history of philosophy. His emphasis on the limitations of sensory perception and the need for deeper understanding influenced later thinkers such as Plato and the Stoics. Plato, in particular, was drawn to Heraclitus’ idea that the world of appearances is in a constant state of flux and that true knowledge lies in grasping the eternal truths that underlie this flux. The Stoics, on the other hand, were influenced by Heraclitus’ concept of the Logos and his belief that wisdom involves living in accordance with the rational order of the universe.

In modern philosophy, Heraclitus’ views have resonated with existentialist thinkers who emphasize the fluid and contingent nature of human existence. Existentialists like Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger drew on Heraclitus’ ideas about the constant flux of the world and the need for individuals to create meaning in the face of this uncertainty. Nietzsche, in particular, admired Heraclitus for his rejection of absolute truths and his embrace of life’s contradictions.

Heraclitus’ insights into the nature of knowledge and wisdom continue to challenge and inspire philosophers today. His belief that wisdom involves recognizing the unity of opposites and embracing the constant flux of the world offers a profound and often unsettling view of reality. Yet, it is this very complexity and tension that makes Heraclitus’ philosophy so enduring and relevant. He reminds us that true understanding requires more than just surface-level knowledge—it demands a deep engagement with the ever-changing, interconnected nature of existence.

Influence and Legacy: Heraclitus in Later Philosophy

Heraclitus’ philosophy left a profound impact on the history of thought, influencing not only his contemporaries but also a wide range of later philosophical traditions. His ideas about flux, the unity of opposites, and the Logos resonated with thinkers from various schools, shaping the development of Western philosophy.

One of the earliest and most significant influences of Heraclitus can be seen in the works of Plato. While Plato was more closely associated with the philosophy of Parmenides—who posited that change is an illusion and that true reality is unchanging—he nevertheless engaged with Heraclitus’ ideas. In particular, Plato’s concept of the realm of Forms, where eternal and unchanging truths exist, can be seen as a response to Heraclitus’ emphasis on the flux of the material world. Plato acknowledged the changing nature of the physical world, but he sought to locate a deeper, unchanging reality behind it. This duality between the world of becoming (change) and the world of being (eternal truths) reflects an attempt to reconcile Heraclitus’ and Parmenides’ opposing views.

Aristotle, too, grappled with Heraclitus’ ideas, especially in his metaphysics. While Aristotle did not accept Heraclitus’ doctrine of perpetual flux in its entirety, he was influenced by the notion that change and development are fundamental aspects of reality. Aristotle’s concept of potentiality and actuality—the idea that all things have the potential to change and become something else—can be seen as an attempt to integrate Heraclitus’ insights into a more systematic philosophical framework.

Perhaps the most direct influence of Heraclitus can be found in the Stoic school of philosophy, which flourished in the Hellenistic period. The Stoics were deeply influenced by Heraclitus’ concept of the Logos, which they interpreted as the rational principle that pervades and organizes the cosmos. For the Stoics, living in accordance with the Logos was the key to achieving a virtuous and fulfilling life. They saw the Logos as not only governing the natural world but also providing a guide for human behavior. This idea of aligning oneself with the rational order of the universe became a central tenet of Stoic ethics.

The Stoics also drew on Heraclitus’ views on the unity of opposites, which they applied to their understanding of fate and providence. They believed that everything in the universe, including apparent opposites like pleasure and pain, good and evil, was part of a harmonious whole governed by the Logos. This Stoic interpretation of Heraclitus’ philosophy had a lasting influence on later Roman thinkers such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, who emphasized the importance of accepting the natural order of things and cultivating inner peace in the face of life’s challenges.

Heraclitus’ ideas also resonated with Neoplatonism, a later development in Greek philosophy that sought to synthesize Plato’s metaphysical ideas with more mystical and religious elements. Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, incorporated Heraclitus’ concept of the unity of opposites into his own philosophical system. For Plotinus, the One, or the ultimate source of all existence, transcends all dualities and opposites, yet it also generates the multiplicity of the world. This notion of a higher unity that encompasses all contradictions echoes Heraclitus’ belief in the underlying harmony of the cosmos.

In addition to his influence on ancient philosophy, Heraclitus’ ideas have had a lasting impact on modern thought. The 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was particularly drawn to Heraclitus, whom he regarded as one of the greatest pre-Socratic thinkers. Nietzsche admired Heraclitus for his rejection of fixed truths and his embrace of life’s inherent contradictions. Nietzsche’s concept of the “eternal recurrence,” the idea that all events in the universe repeat themselves infinitely, can be seen as an extension of Heraclitus’ doctrine of perpetual flux.

Nietzsche also saw in Heraclitus a kindred spirit in his critique of conventional morality and religion. Like Heraclitus, Nietzsche believed that traditional moral values were based on a misunderstanding of the nature of existence. Both philosophers rejected the idea of absolute good and evil, instead emphasizing the creative power of conflict and opposition. Nietzsche’s philosophy of the “will to power,” which posits that life is driven by a fundamental force of creation and destruction, echoes Heraclitus’ belief in the generative power of strife.

Heraclitus’ influence extends beyond philosophy to the realm of science, particularly in modern physics. The idea that the universe is in a constant state of flux and transformation resonates with contemporary scientific theories about the dynamic nature of reality. Quantum mechanics, for example, reveals a world where particles are in constant motion, and where uncertainty and probability govern the behavior of matter at the smallest scales. In this sense, Heraclitus’ vision of a universe defined by change and transformation can be seen as a precursor to modern scientific understandings of the cosmos.

Heraclitus’ impact on existentialist thought is also significant. Existentialist philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre were drawn to Heraclitus’ emphasis on the fluid and contingent nature of existence. Heidegger, in particular, saw Heraclitus as a precursor to his own philosophy of being. He admired Heraclitus’ focus on the dynamic nature of existence and his critique of the conventional ways of understanding the world. For Heidegger, Heraclitus represented a way of thinking that was closer to the original experience of being, before it became obscured by abstract concepts and fixed categories.

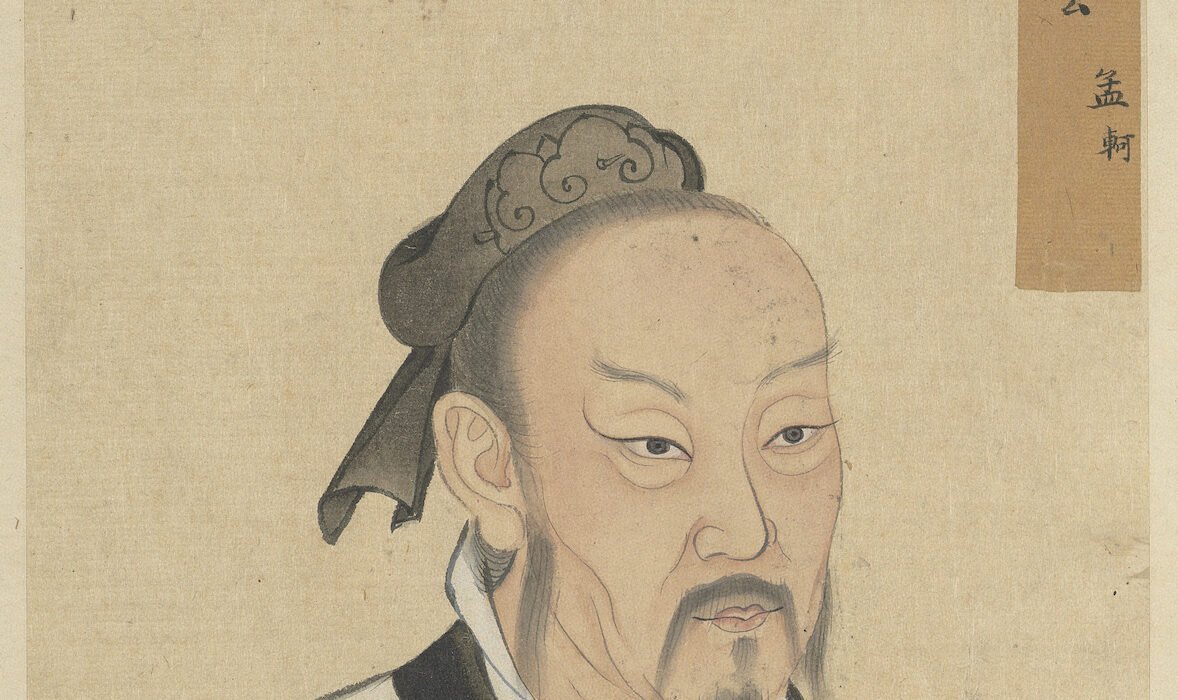

In the 20th century, Heraclitus’ ideas continued to influence a wide range of thinkers, from process philosophers like Alfred North Whitehead, who emphasized the dynamic and relational nature of reality, to deconstructionist thinkers like Jacques Derrida, who explored the instability and fluidity of meaning. Heraclitus’ belief in the fluidity and constant transformation of all things has permeated modern thought, influencing not only philosophy but also literature, art, and psychology. His idea that “everything flows” resonates with the modern understanding that change is an inherent and inescapable aspect of life. In particular, process philosophy, which focuses on becoming and change rather than static being, finds a precursor in Heraclitus’ work. Thinkers like Alfred North Whitehead have developed complex metaphysical systems based on the idea that reality is fundamentally characterized by process and change, rather than by enduring substances.

In literature, Heraclitus’ ideas have been echoed by writers who explore themes of impermanence, transformation, and the cyclical nature of existence. For example, the 20th-century novelist Virginia Woolf, with her stream-of-consciousness technique, reflects Heraclitus’ notion of flux in the way she portrays the inner lives of her characters. Her works often emphasize the transient nature of experience and the fluid boundaries between past, present, and future. This literary exploration of time and change can be seen as a reflection of Heraclitus’ belief that everything is in constant motion and that identity itself is something dynamic and evolving.

In the visual arts, Heraclitus’ influence is evident in movements that emphasize transformation and flux. The Cubist movement, for example, with its fragmented and shifting perspectives, can be seen as a visual representation of Heraclitus’ philosophy. Artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque sought to capture multiple viewpoints and the fluidity of time in their work, echoing Heraclitus’ notion that reality is not fixed but constantly changing. Similarly, the abstract expressionists, with their emphasis on process and the dynamic interplay of form and color, can be seen as engaging with the Heraclitean idea that the world is a place of constant flux and transformation.

In psychology, Heraclitus’ influence can be seen in the works of thinkers like Carl Jung, who explored the dynamic tension between opposites within the human psyche. Jung’s concept of the “shadow” and the integration of opposites in the process of individuation reflects Heraclitus’ idea that opposites are necessary for wholeness and that conflict and tension are essential to the process of becoming. Jung’s exploration of the unconscious mind and the interplay between conscious and unconscious forces in shaping the self can be seen as a psychological extension of Heraclitus’ belief in the unity of opposites and the dynamic nature of reality.

Heraclitus’ legacy also resonates in contemporary discussions about the nature of time and existence. Philosophers and scientists alike continue to grapple with the implications of his ideas about change, identity, and the fundamental nature of reality. In discussions about the nature of time, for example, Heraclitus’ idea that everything is in a state of flux challenges the notion of a static, linear progression of events. Instead, his philosophy suggests a more fluid and interconnected understanding of time, one that resonates with contemporary theories in both physics and philosophy.

Heraclitus’ belief that wisdom lies in recognizing the interconnectedness of all things and embracing the constant flux of the world offers a profound and often challenging perspective on life. His ideas encourage us to look beyond the surface of things, to question fixed categories and rigid boundaries, and to engage with the dynamic and ever-changing nature of reality. In this way, Heraclitus’ philosophy continues to inspire and challenge us, reminding us that the pursuit of wisdom is not about finding final answers but about embracing the complexity and fluidity of life itself.

Throughout history, Heraclitus’ philosophy has been a source of inspiration and a catalyst for intellectual exploration. His ideas about flux, opposites, and the Logos have left an indelible mark on the history of thought, influencing a wide range of disciplines from philosophy and science to art and literature. His legacy reminds us that the world is a place of constant change and that wisdom lies in embracing this reality rather than resisting it. In this sense, Heraclitus’ thought remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Greece, offering a timeless reflection on the nature of existence and the human condition.