Before there were nations, borders, or written language, there were stories. Around flickering fires and under ancient stars, early humans told tales—of gods and monsters, creation and destruction, heroes and tricksters. These myths were not mere entertainment; they were blueprints of belief, culture, and identity. Yet, astonishingly, many of these myths echo across vast distances. Civilizations separated by oceans or millennia often share similar legends. Why do so many cultures have a great flood myth? Why do trickster gods appear in Africa, the Americas, and Scandinavia? How did stories spread so far and wide in times when travel was difficult and slow?

This article explores one of the most fascinating phenomena in human history—the transmission of myth across borders and civilizations. It is a story of migration, trade, conquest, memory, and imagination. A story that shows how myth is not confined by geography, but instead flows like a river—changing shape, absorbing local colors, and yet retaining a universal rhythm.

The Nature of Myth: Beyond Fiction and Fantasy

To understand how myths spread, we must first understand what a myth is. Contrary to popular belief, myths are not simply false stories. They are symbolic narratives that encode a culture’s values, fears, hopes, and explanations of the world. A myth tells not just what happened, but why it matters. It answers questions that science could not, or had not yet answered: Why does the sun rise? Where do we go after death? Why do people suffer?

Myths often emerge spontaneously within a culture, shaped by local landscapes, events, and worldviews. But they are also remarkably portable. They can leap across regions, languages, and belief systems. And once planted in a new cultural soil, they bloom anew—sometimes subtly altered, sometimes wildly transformed, but always rooted in deep psychological and social needs.

Oral Traditions and the Power of Memory

Long before the invention of writing, myths were preserved through oral tradition. Skilled storytellers memorized epic tales, sometimes thousands of lines long, and recited them at gatherings, festivals, or sacred ceremonies. These oral traditions were highly fluid. Every retelling might introduce a new detail, drop an outdated one, or adapt to the audience. This flexibility allowed myths to evolve naturally over time and space.

When tribes migrated, they took their stories with them. A hunter-gatherer band relocating due to climate change might bring along the legend of a sky-god or an ancestral animal. As they encountered new peoples, stories were exchanged like gifts. The merging of traditions enriched both sides. Myths spread not only because they were memorable—but because they were adaptable.

Migration: Carrying the Mythic Fire

Human history is a history of movement. From the earliest out-of-Africa migrations to the peopling of the Americas, from the Indo-European dispersals to the Silk Road caravans, people have moved—and with them, myths.

Take the Indo-Europeans, for example. This vast language family—spanning Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, Celtic, Persian, and many modern tongues—likely originated from a common source thousands of years ago. Alongside language, these ancient peoples carried myths of thunder gods, cosmic battles, and world trees. Scholars have traced similarities between the Indian god Indra and the Norse god Thor, or between the Rigveda’s sacred cow and the Greek myth of Io. These parallels are not coincidental. They are remnants of shared cultural ancestry.

Similarly, the Bantu migrations across sub-Saharan Africa carried origin myths and trickster tales—like that of Anansi the spider—that later crossed the Atlantic with enslaved Africans, taking root in Caribbean and African-American folklore.

Migration allows myth to travel not just across geography, but through generations. A story born in one land can be reborn in another—different in name, familiar in soul.

Trade Routes: Highways of Ideas

Trade was not merely the exchange of goods—it was the exchange of ideas, beliefs, and myths. Along trade routes, merchants carried silks, spices, and silver, but they also brought stories. Ports, caravanserais, and markets were melting pots of culture. In these hubs, Egyptian merchants could share tales with Phoenician sailors, and Arab traders could hear Buddhist legends from Indian monks.

The Silk Road is a prime example. Stretching from China to the Mediterranean, it was a corridor of mythic transmission. Buddhist stories traveled westward to influence Gnostic and Christian texts. Zoroastrian ideas merged with Mesopotamian cosmologies. Even distant Celtic and Chinese myths show surprising overlaps, likely due to long chains of indirect transmission.

Maritime trade also played a role. Indonesian sailors brought Hindu epics to Southeast Asia, where they were adapted into local myths. The Ramayana, originally Indian, became deeply embedded in Javanese, Thai, and Cambodian cultures—illustrating how myth can be both imported and indigenized.

Conquest and Empire: The Sword and the Scroll

Empires often imposed political control, but they also triggered cultural exchange—sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental. Conquerors brought their gods, epics, and rituals. The Romans, for instance, absorbed Greek mythology almost wholesale, changing names but preserving the core narratives. Jupiter was Zeus, Venus was Aphrodite, Mars was Ares.

But the flow went both ways. Local deities were often integrated into imperial pantheons. In Egypt, when Alexander the Great established the Hellenistic city of Alexandria, Greek and Egyptian myths blended. Isis became associated with Demeter; Serapis was a fusion of Osiris and Greek deities.

Christianity, too, spread through empire but adapted itself along the way. Pagan festivals were transformed into Christian holidays. Saints inherited the traits of older gods. In Mexico, the Virgin of Guadalupe echoes earlier Aztec goddesses like Tonantzin. This syncretism shows that myth is not easily erased—it morphs.

Conquest can destroy libraries and temples, but it also creates bridges between myths. Even as languages fall silent, stories whisper their way into new tongues.

Common Human Experience: Why Some Myths Arise Everywhere

Not all similarities in myth result from transmission. Some myths arise independently in multiple cultures because they reflect universal human experiences. Flood myths are found from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica. Why? Because floods are a common and terrifying natural disaster. To ancient people, a flood could seem like divine punishment or cosmic cleansing.

Likewise, many cultures have myths about the sun and moon chasing each other, the underworld journey of a hero, or a world created from chaos. These motifs may reflect psychological archetypes—a term made famous by Carl Jung. According to Jung, humans share a collective unconscious filled with symbolic patterns. These archetypes manifest in myths, dreams, and art.

So, when distant cultures dream of sky gods or mother earths, it’s not always due to contact. Sometimes it’s because the human brain, shaped by evolution, tends to generate similar narratives in response to similar existential questions.

Storytellers, Scribes, and Shamans: Carriers of the Myth

Certain individuals have always played a key role in spreading myth. The bard who recites epics in a king’s court. The shaman who chants ancestral tales. The monk who copies manuscripts in candlelight. These cultural transmitters keep myths alive, modify them, and pass them on.

In ancient Mesopotamia, scribes recorded the Epic of Gilgamesh—a story so powerful it influenced later Greek and biblical texts. In India, rishis memorized the Vedas and passed them down orally with astounding precision. In West Africa, griots preserved genealogies and legends through song and rhythm.

These storytellers were not mere entertainers—they were custodians of cultural memory. As they traveled or were invited to new courts and regions, they seeded myths across borders, often subtly altering them to suit new audiences.

Artistic Media: Myth Through Stone, Paint, and Song

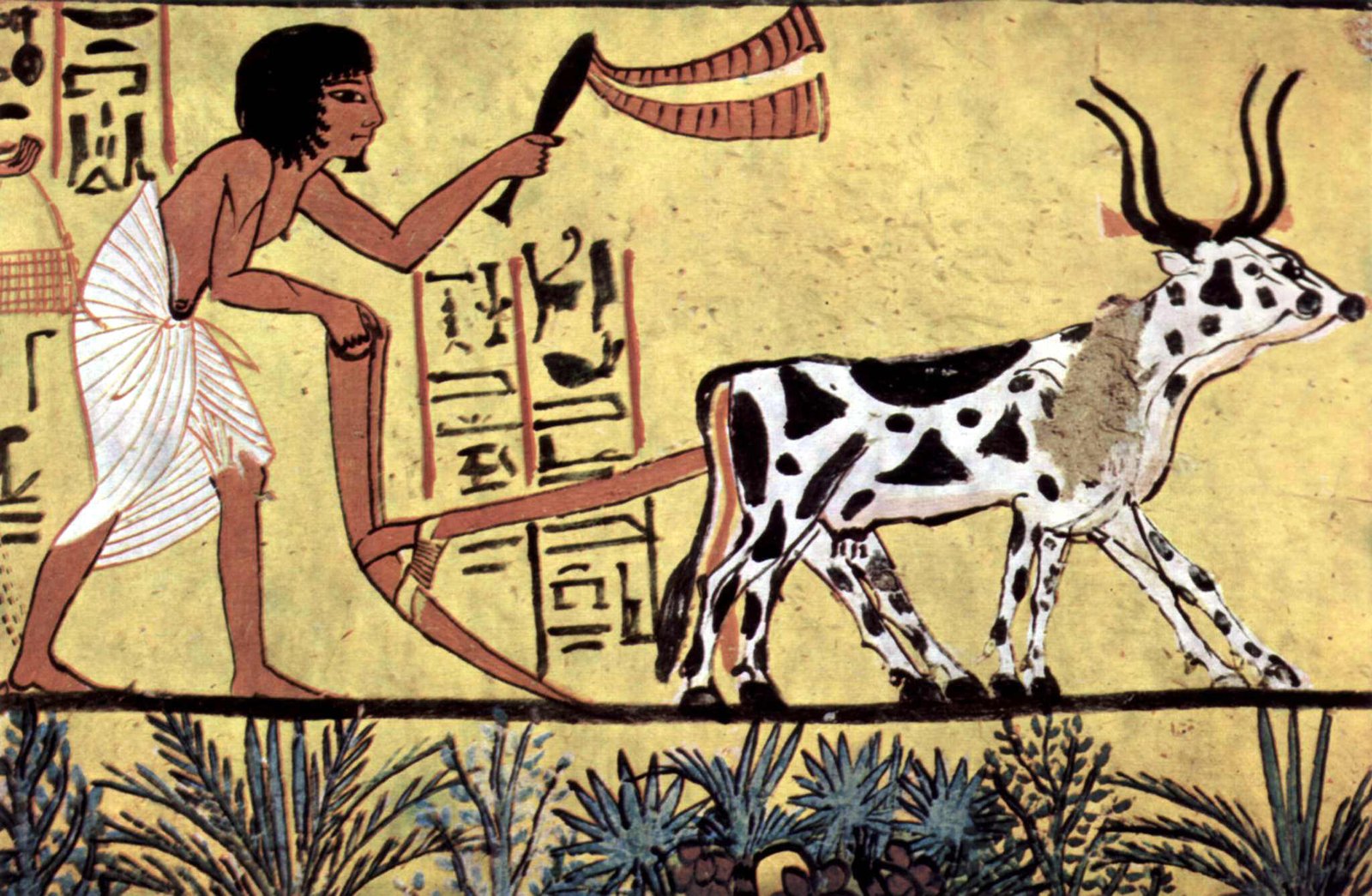

Myths don’t live only in words. They are etched in stone, painted on cave walls, woven into textiles, danced in rituals, and sung in lullabies. Artistic expression allows myth to spread without language barriers.

Consider the recurring image of the “Tree of Life,” found in Assyrian reliefs, Norse legends, and Mayan temples. Or the motif of the serpent, which appears as a protector in Chinese lore, a deceiver in the Bible, and a world-encircling force in Norse myth. These symbols transcend words and borders.

Pilgrims and artists carried these motifs from temple to temple, court to court. Stained glass windows told biblical stories to the illiterate. Balinese shadow puppets performed Hindu epics for village audiences. Art became a vector for myth, capable of crossing oceans.

Transformation Through Time: Myths in New Clothes

As myths travel, they change. A storm god in one culture may become a dragon slayer in another. A creation myth may absorb local geography. These transformations are not distortions—they are adaptations. They allow myths to survive by evolving.

The Norse god Odin, for instance, shares traits with the Vedic Varuna and the Celtic Lugh—wise, one-eyed, associated with magic and fate. The myth changes clothing but keeps its soul.

In medieval Europe, ancient pagan myths were Christianized. Fairy tales like Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty have ancient roots but were reshaped by oral transmission and literary retellings. Even modern media—movies, novels, video games—continue to adapt ancient myths for contemporary audiences.

In this way, myths are immortal. They survive by becoming new.

Modern Parallels: The Internet and the Revival of Myth

Today, myths travel faster than ever. The internet acts as a global campfire, connecting storytellers across continents. Revivals of Norse mythology in popular culture, anime inspired by Shinto legends, African folktales in graphic novels—these show that myth is alive and adaptive.

Even conspiracy theories and urban legends function as modern myths. They explain the unknown, enforce social values, or channel collective anxieties. Whether it’s Bigfoot or UFOs, Area 51 or Atlantis, these tales reflect age-old mythic structures.

The transmission of myth today mirrors the past—fluid, borderless, and deeply human.

Conclusion: Myths as the DNA of Humanity

How do myths spread across borders and civilizations? They travel through mouths and memories, across trade routes and seas, within the minds of migrants and the art of empires. They evolve in response to new landscapes but retain the heartbeat of the past. They arise from shared fears and dreams, born not just from contact, but from the deep wells of human consciousness.

Myths are not static relics of ancient times. They are living, breathing narratives that adapt to each generation. They are the DNA of culture, the spiritual maps of our ancestors, and the stories that make us human.

No matter where you are in the world, when you listen to a myth, you are not just hearing a story. You are touching a thread in the great web of human imagination—woven across borders, spun over millennia, and still whispering its truths today.