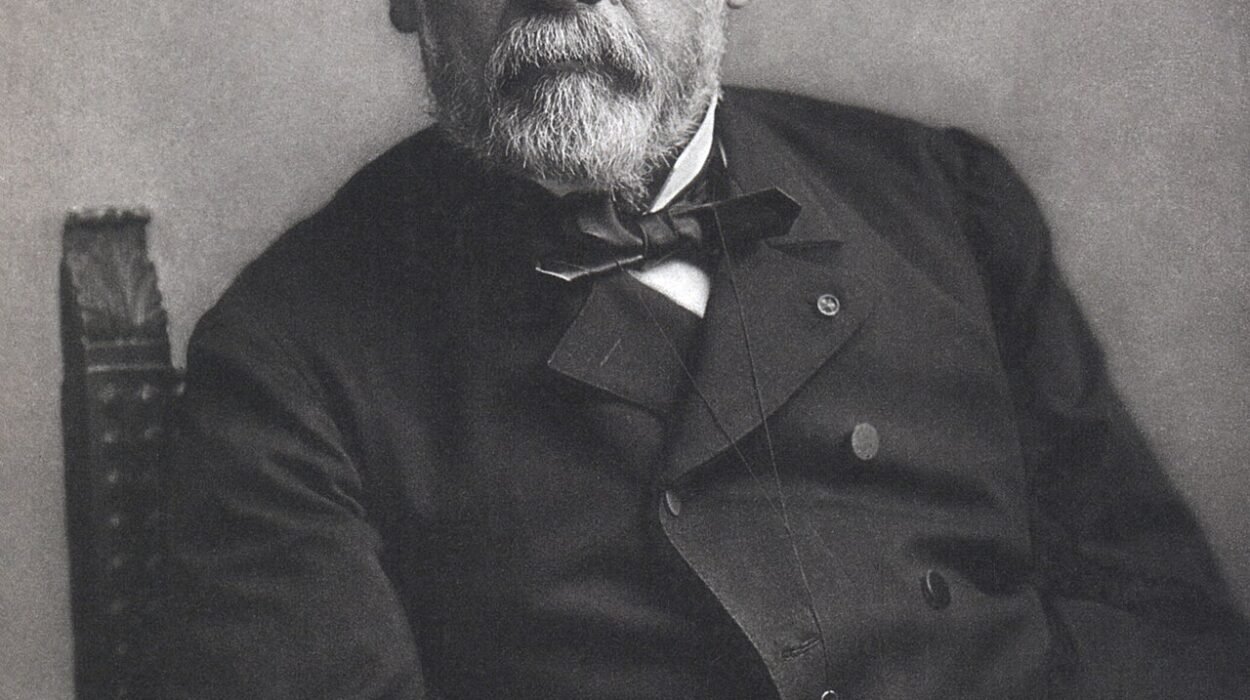

Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) was a French artist and inventor who is best known for developing the daguerreotype, the first commercially successful photographic process. A skilled painter and theater designer, Daguerre initially gained fame for his work in dioramas, but his collaboration with inventor Nicéphore Niépce in the 1820s led to groundbreaking advancements in photography. After Niépce’s death, Daguerre continued their work and, in 1839, introduced the daguerreotype to the world. This process produced highly detailed images on silver-plated copper sheets and quickly became popular for portraiture and landscape photography. The invention of the daguerreotype marked a pivotal moment in the history of visual arts, transforming the way people captured and perceived the world around them. Daguerre’s contribution to photography earned him recognition as one of the pioneers of the medium, cementing his place in the annals of art and technology.

Early Life and Formative Years

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was born on November 18, 1787, in the small town of Cormeilles-en-Parisis, France. He was born into a modest family, with his father serving as a clerk in a local office. From a young age, Daguerre showed a natural inclination towards art, with a particular fascination for drawing and painting. His talents were nurtured despite the limited resources available to his family, and by his teenage years, he was already recognized for his artistic abilities.

In pursuit of greater opportunities, Daguerre moved to Paris as a young man. Paris, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was a bustling hub of artistic and intellectual activity, offering Daguerre the perfect environment to develop his skills. He initially worked as an apprentice to an architect, which provided him with a solid foundation in the principles of design and perspective. This experience was crucial for his later work in theater and photography.

Daguerre’s passion for art led him to study under the renowned stage designer Pierre Prévost, where he developed a keen interest in scenic painting and set design. His work in theater design allowed him to experiment with light and illusion, foreshadowing his later contributions to photography. By the time he reached his mid-twenties, Daguerre had established himself as a talented scene painter, known for his ability to create realistic and captivating images on stage.

Despite his growing success in the arts, Daguerre was not content to limit himself to traditional forms of expression. The scientific advancements of his time, particularly in the fields of optics and chemistry, intrigued him. He became increasingly interested in the idea of capturing images permanently, a challenge that would occupy much of his later life. The convergence of his artistic talents and scientific curiosity would ultimately lead to his groundbreaking contributions to the world of photography.

The Diorama: A Theatrical Innovation

Before his revolutionary work in photography, Louis Daguerre achieved significant fame through his invention of the diorama, a form of entertainment that combined art, science, and theater. The diorama was a large-scale display that used painted scenes, lighting effects, and mechanical devices to create a realistic illusion of movement and change. Audiences were captivated by the diorama’s ability to depict natural phenomena, historical events, and exotic landscapes with astonishing realism.

Daguerre developed the diorama in the early 1820s, drawing on his experience as a scene painter and his understanding of optics. The diorama consisted of a large, translucent painting, typically measuring about 22 feet high and 70 feet wide. These paintings were mounted on a frame and could be viewed from different angles. The key to the diorama’s success was the use of carefully controlled lighting, which allowed Daguerre to simulate changes in time, weather, and atmosphere. For example, by adjusting the light sources, Daguerre could make a scene transition from day to night, or from clear skies to a thunderstorm.

The diorama became an instant success when it debuted in Paris in 1822. Audiences were amazed by the lifelike quality of the scenes and the dramatic effects created by the changing light. The diorama’s popularity quickly spread, and Daguerre opened diorama theaters in other cities, including London. The revenue generated from these theaters provided Daguerre with financial security and allowed him to continue his artistic and scientific pursuits.

The diorama was not only a commercial success but also an important step in Daguerre’s journey towards photography. The techniques he developed for creating and manipulating light in the diorama would later prove invaluable in his experiments with capturing images. The diorama’s emphasis on realism and the illusion of depth also reflected Daguerre’s growing interest in finding a way to permanently capture the world around him. This fascination with realism would eventually lead him to invent the daguerreotype, a process that revolutionized visual representation.

The Partnership with Nicéphore Niépce

Louis Daguerre’s pursuit of a method to permanently capture images led him to collaborate with another pioneering figure, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Niépce was a French inventor who had been experimenting with early forms of photography since the 1810s. In 1826, Niépce created the first known permanent photograph using a process he called “heliography,” which involved exposing a bitumen-coated plate to light for several hours.

Daguerre learned of Niépce’s work in 1826 and was immediately intrigued by the possibilities it presented. Although Niépce’s heliographs were a remarkable achievement, they were not yet practical for widespread use due to the lengthy exposure times and the poor quality of the images. Daguerre recognized the potential for improvement and saw an opportunity to combine his artistic skills with Niépce’s scientific knowledge.

In 1829, Daguerre and Niépce entered into a formal partnership, with the goal of refining and improving the photographic process. Over the next few years, the two men worked together to experiment with different chemicals and techniques, trying to find a way to reduce exposure times and improve image clarity. While their collaboration was fruitful, progress was slow, and the process remained complex and unpredictable.

Tragically, Niépce passed away in 1833, leaving Daguerre to continue their work alone. Although Daguerre was deeply affected by the loss of his partner, he remained determined to fulfill their shared goal. Drawing on the knowledge he had gained from Niépce, Daguerre continued to experiment with various materials and processes. His persistence paid off in 1837 when he made a breakthrough that would change the course of history.

The partnership between Daguerre and Niépce was a pivotal moment in the development of photography. Niépce’s early experiments laid the foundation for the work that Daguerre would later complete, and together, they helped transform the dream of capturing images into a practical reality. The success of their collaboration demonstrated the power of combining artistic vision with scientific innovation, a combination that would define Daguerre’s legacy.

The Invention of the Daguerreotype

Louis Daguerre’s most significant achievement came in 1837 when he developed the daguerreotype, the first practical and commercially viable photographic process. The daguerreotype was a remarkable advancement over previous attempts at photography, offering unprecedented clarity, detail, and permanence. It marked the beginning of the modern era of photography and established Daguerre as one of the most important inventors of the 19th century.

The daguerreotype process involved several steps. First, a silver-plated copper sheet was polished to a mirror-like finish. The plate was then exposed to iodine vapor, which created a light-sensitive layer of silver iodide on the surface. Once prepared, the plate was placed in a camera and exposed to light for several minutes. After exposure, the plate was developed by exposing it to mercury vapor, which brought out the latent image. The final step involved fixing the image by immersing the plate in a solution of salt or sodium thiosulfate, which removed the remaining light-sensitive chemicals and made the image permanent.

The result was a highly detailed, positive image that could not be replicated—a unique artifact. Unlike previous photographic processes, the daguerreotype required much shorter exposure times, making it suitable for portrait photography. The level of detail captured by the daguerreotype was astonishing; viewers could see individual hairs, fabric textures, and even the reflections in a subject’s eyes.

Recognizing the significance of his invention, Daguerre sought to share it with the world. In 1839, he and Isidore Niépce (the son of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce) negotiated with the French government to present the daguerreotype as a “gift to the world.” In exchange, Daguerre and Isidore were granted lifetime pensions. On August 19, 1839, the daguerreotype was officially unveiled at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. The announcement was met with widespread acclaim, and news of the invention quickly spread across Europe and North America.

The daguerreotype was an instant success, ushering in a new era of visual culture. For the first time, people could capture and preserve accurate images of themselves, their loved ones, and their surroundings. The process became so popular that the 1840s and 1850s are often referred to as the “Daguerreian era.” Daguerre’s invention not only revolutionized art and science but also had profound social and cultural implications, shaping the way people viewed themselves and their world.

The Global Impact of the Daguerreotype

The introduction of the daguerreotype in 1839 had a profound impact on society, culture, and the arts. As the first practical method of photography, the daguerreotype quickly spread across Europe and North America, becoming a global phenomenon. Its influence extended far beyond the realm of science and technology, affecting how people perceived and interacted with the world around them.

One of the most significant effects of the daguerreotype was its democratization of portraiture. Before the invention of photography, having a portrait made was a privilege reserved for the wealthy, who could afford to commission a painter. The daguerreotype changed this by making portraiture accessible to a much broader segment of society. People from all walks of life could now have their likenesses captured, creating a visual record of individuals, families, and communities that had never existed before.

The daguerreotype also played a crucial role in documenting historical events and places. Early photographers used the process to capture images of wars, political events, urban landscapes Early photographers used the process to capture images of wars, political events, urban landscapes, and other scenes of historical significance. The Crimean War (1853-1856) was among the first conflicts to be extensively documented through photography, providing the public with an unprecedented visual account of the horrors of war. Similarly, daguerreotypes of political figures, public demonstrations, and notable landmarks offered a new way to record and disseminate information, making history more tangible and accessible to a wider audience.

The daguerreotype also had a profound impact on art and culture. Artists began to use photography as a tool for studying nature, human anatomy, and composition. The ability to capture and study details that the human eye might miss allowed artists to explore new levels of realism in their work. At the same time, the daguerreotype influenced the development of other artistic movements, such as realism and impressionism, by providing new ways of seeing and interpreting the world.

On a broader scale, the daguerreotype contributed to the rise of modern visual culture. It paved the way for the development of mass media, as photographs became an essential part of newspapers, magazines, and books. The ability to capture and share images had far-reaching implications for communication, education, and even propaganda. The daguerreotype’s impact can still be felt today, as photography continues to shape how we document, understand, and remember the world.

Legacy and Later Life

The success of the daguerreotype secured Louis Daguerre’s place in history as a pioneering figure in the development of photography. However, as the medium evolved, the daguerreotype eventually became obsolete, replaced by more advanced photographic techniques. Despite this, Daguerre’s contribution to the field was undeniable, and his name became synonymous with the birth of modern photography.

After the invention of the daguerreotype, Daguerre continued to work as an artist and inventor, though none of his subsequent projects achieved the same level of recognition. As photography gained popularity and new methods were developed, Daguerre’s influence began to wane, but he remained a respected figure in both scientific and artistic circles. In 1839, Daguerre was awarded a pension by the French government in recognition of his contributions to science and art. This pension allowed him to retire comfortably and focus on his remaining projects and personal interests.

During the later years of his life, Daguerre lived quietly in Bry-sur-Marne, a small village near Paris. His health began to decline, and he became less active in the public eye. Nevertheless, he continued to experiment with various ideas, though none reached the prominence of the daguerreotype. Despite the passage of time, Daguerre’s legacy as a visionary and innovator remained intact.

Louis Daguerre passed away on July 10, 1851, at the age of 63. He was buried in the local cemetery of Bry-sur-Marne, where a monument was erected in his honor. His death marked the end of an era, but his influence on photography and visual culture continued to resonate for generations. Daguerre’s work had laid the foundation for a new form of expression, one that would change how people recorded and remembered their lives.

The legacy of Louis Daguerre is evident in the continued evolution of photography. While the daguerreotype was eventually replaced by more advanced methods, its impact on art, science, and society was profound. Daguerre’s invention democratized image-making and set the stage for the development of the photographic industry, which would go on to revolutionize communication, journalism, and culture in the 20th and 21st centuries. Today, Daguerre is celebrated as one of the founding figures of photography, a man whose vision and determination opened up new possibilities for capturing and sharing the world.

The Evolution of Photography Post-Daguerre

While Louis Daguerre’s invention of the daguerreotype was groundbreaking, the field of photography continued to evolve rapidly after his death. The limitations of the daguerreotype—such as the inability to produce multiple copies of an image and the lengthy exposure times—spurred further experimentation and innovation. By the 1850s, the daguerreotype had begun to be eclipsed by new photographic processes that addressed its shortcomings.

One of the most significant of these was the calotype, developed by the English scientist William Henry Fox Talbot. Unlike the daguerreotype, which produced a unique, one-of-a-kind image on a metal plate, the calotype process involved creating a paper negative that could be used to make multiple positive prints. This development was revolutionary, as it allowed for the mass production of photographic images, something that the daguerreotype could not achieve. The calotype also required less exposure time, making it more practical for various applications.

Another major advancement came with the invention of the wet collodion process by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, the same year Daguerre passed away. The wet collodion process combined the clarity of the daguerreotype with the reproducibility of the calotype, offering photographers a new level of flexibility and quality. This process quickly became the dominant method of photography throughout the second half of the 19th century.

Despite the decline of the daguerreotype, Daguerre’s influence endured. His invention had set the stage for the rapid advancements that followed, and his name continued to be associated with the early history of photography. As photography became more accessible and widespread, it began to play a crucial role in documenting history, shaping public opinion, and influencing art and culture. Daguerre’s legacy lived on in the countless photographs that captured the changing world.

The evolution of photography after Daguerre demonstrates the dynamic nature of technological innovation. While Daguerre’s daguerreotype was eventually surpassed by more advanced processes, it remains a symbol of the ingenuity and creativity that define the history of photography. The journey from the daguerreotype to modern digital photography reflects the ongoing pursuit of better, faster, and more versatile ways to capture and share the world around us.