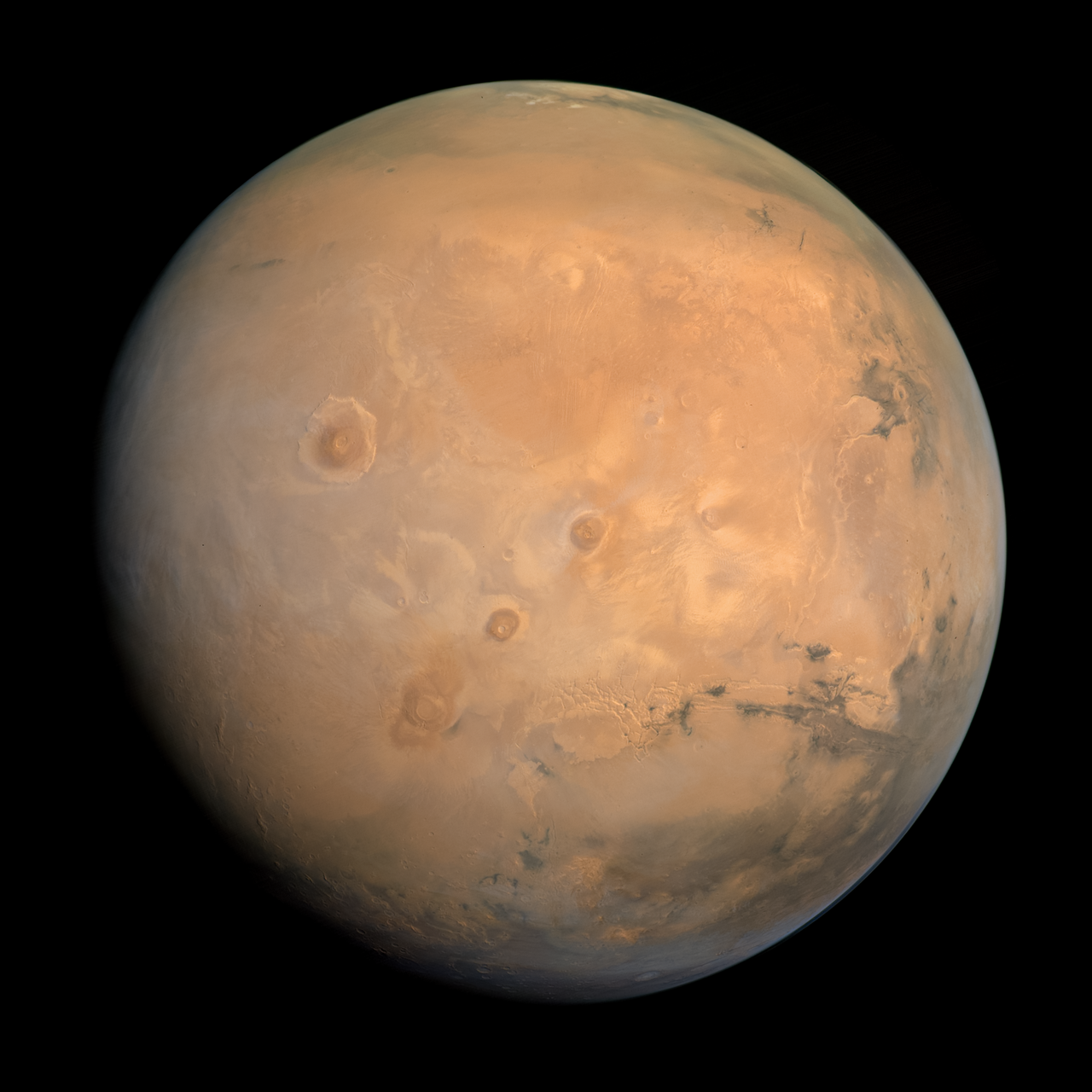

For as long as humans have gazed upward, Mars has stared back—a rusty ember glowing against the black velvet of night. To ancient eyes, it was a wandering star that burned with the color of blood and fire. The Babylonians named it Nergal, the god of war. The Romans saw Mars, their divine warrior. Its crimson hue stirred the imagination of every civilization that looked skyward, evoking awe, fear, and fascination in equal measure.

But Mars is no god. It is a real world, the fourth planet from the Sun, circling the same star that warms Earth, yet existing in a vastly different realm. It is smaller, colder, and lonelier—a desert of dust and rock, carved by ancient rivers that have long since vanished. And yet, despite its desolation, Mars has become humanity’s greatest dream. It is the frontier that calls to us—the next step in our cosmic journey, the place where we might one day plant our flag, build our homes, and extend the story of life beyond Earth.

Mars is not just a planet. It is a mirror of our own hopes and fears, a stage upon which we project the oldest human question: Are we alone?

The Red Planet’s Allure

Seen through a telescope, Mars is unmistakable—a disk tinted in deep orange and ochre, with dark patches and shifting white caps at its poles. It is the only planet whose surface features are visible from Earth, and this visibility has fueled centuries of speculation.

In the 19th century, astronomers like Giovanni Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell believed they saw long, straight lines crossing Mars’s surface. Lowell called them “canals” and suggested they were the work of intelligent beings—perhaps a dying civilization struggling to irrigate its desert world. Though later proven false, the idea gripped the public imagination and gave rise to endless tales of Martians, from H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds to Ray Bradbury’s haunting The Martian Chronicles.

But even after science stripped away the fantasy of canals and cities, the fascination with Mars endured. It remained a world tantalizingly Earth-like, a place that could almost, almost support life. And as spacecraft began to visit the Red Planet, what they revealed was even more compelling than fiction—a world once shaped by rivers, lakes, and perhaps even oceans, frozen now in time, waiting for us to uncover its secrets.

A Small, Dying World

Mars orbits the Sun at an average distance of about 228 million kilometers, roughly one and a half times farther than Earth. It is only about half the size of our planet, with a diameter of 6,779 kilometers, and its gravity is just 38% of Earth’s. If you weigh 60 kilograms on Earth, you’d weigh barely 23 kilograms on Mars.

This smaller size has shaped the planet’s destiny. With less mass, Mars could not hold on to a thick atmosphere. Over billions of years, the solar wind stripped away much of its air, leaving a thin, ghostly envelope of carbon dioxide—less than 1% the density of Earth’s atmosphere at sea level. Without that protective blanket, heat escapes easily into space, and the surface freezes.

Today, average temperatures hover around –63°C, though at the equator on a sunny day they can briefly rise to near 20°C before plunging to –100°C at night. Dust storms, sometimes covering the entire planet, sweep across the barren plains. The sky glows a faint butterscotch color, tinged red by fine dust suspended in the air.

Mars is a frozen desert, a graveyard of what might have been. Yet the very fact that it once had rivers and valleys tells us it was not always this way. Once, long ago, Mars may have been alive.

The Evidence of Ancient Water

If you could stand on Mars and look to the horizon, you might see something familiar—valleys carved like the channels of ancient rivers, dry deltas spreading into what was once a lakebed, and layers of sediment that speak of water long gone.

Spacecraft like Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Curiosity have shown us that billions of years ago, Mars had flowing water on its surface. Channels like Vallis Marineris—the largest canyon system in the solar system, stretching more than 4,000 kilometers—bear the unmistakable scars of erosion. Crater basins show signs of having once been filled with lakes. Even minerals on the surface, such as clays and sulfates, can form only in the presence of liquid water.

Scientists believe that early Mars had a thicker atmosphere, perhaps supported by volcanic activity that released carbon dioxide and water vapor. With that denser air, the planet could have had a climate warm enough to sustain rivers and maybe even shallow seas.

Then, something changed. The planet’s magnetic field, once generated by its molten core, faded. Without this shield, the solar wind stripped away the atmosphere. The pressure dropped, the water evaporated, and the surface froze. Mars dried out and died slowly—a once-blue world turned to rust.

The Rusted Surface and the Blood-Red Sky

Mars owes its signature color to the iron oxide—rust—that covers its surface. Billions of years of chemical reactions between the planet’s iron-rich rocks and oxygen have painted the world in shades of red, orange, and brown. When sunlight scatters through its dusty atmosphere, the sky itself glows pink or even a faint orange-red, giving Mars its haunting, otherworldly hue.

The dust that coats Mars is fine as talcum powder and clings to everything. During planet-wide storms, it can rise kilometers high, dimming sunlight for weeks. In 2018, such a storm enveloped the entire planet, silencing NASA’s Opportunity rover after 15 years of exploration. The rover’s final message, sent before its solar panels were buried in dust, broke hearts around the world: “My battery is low and it’s getting dark.”

That message captured the loneliness of Mars—the endless quiet of a world without wind, water, or life as we know it. Yet it also reminded us of the enduring human drive to reach across that emptiness.

The Search for Life

Of all the planets in the solar system, Mars has always seemed the most likely to host life. Not the green-skinned Martians of old science fiction, but microbes—tiny, resilient organisms that might once have thrived in its ancient lakes and rivers.

Every robotic mission to Mars has carried with it one central question: Was there ever life here?

NASA’s Viking landers in the 1970s were the first to directly test Martian soil for biological activity. The results were ambiguous—some hinted at chemical reactions resembling metabolism, others contradicted them. The mystery remained unresolved.

In 1996, excitement surged again when scientists studying a Martian meteorite found in Antarctica—known as ALH84001—claimed to have discovered fossilized microbial life. The rock contained strange, worm-like shapes that some believed were microscopic fossils. Later analysis cast doubt on the claim, but the question lingered.

Modern missions like Curiosity, Perseverance, and the European ExoMars program continue the search, not for living organisms but for the chemical signatures they might have left behind. Perseverance, which landed in Jezero Crater in 2021, is exploring what was once an ancient river delta—a place where water, minerals, and organic molecules may have mingled billions of years ago. It is collecting samples that, someday, could be returned to Earth for definitive analysis.

If we find even the faintest trace that life once existed on Mars, it will mean that life is not a miracle of Earth alone—but a natural outcome of the universe’s chemistry.

The Mountains, Canyons, and Frozen Poles

Mars is a planet of extremes. Its landscapes dwarf anything found on Earth, both in scale and in silence.

Towering above all is Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system. It rises 21.9 kilometers high—nearly three times the height of Mount Everest—and spans 600 kilometers across. Its slopes are so gradual that if you stood on them, you might not even realize you were climbing a mountain. The volcano’s immense size suggests that Mars once had volcanic activity lasting for millions of years, fueled by a hot mantle beneath its crust.

To the east lies Valles Marineris, a canyon system that makes Earth’s Grand Canyon look like a scratch in the sand. It stretches a distance equal to the width of the United States and plunges seven kilometers deep. Some scientists believe it began as a crack in the crust, widened by erosion from ancient water or volcanic activity.

At the poles, gleaming ice caps glisten beneath the thin sunlight. These caps are made of water ice layered with frozen carbon dioxide—dry ice—that sublimates into gas during the warmer season, creating thin clouds and wispy frost. Beneath these polar layers lies a record of the planet’s climate, frozen in time, waiting to be read like pages of an ancient diary.

The Sound and Silence of Mars

The first time humans heard the wind of another world was in 2019, when NASA’s InSight lander recorded faint vibrations passing over the Martian surface. The sound was eerie—soft gusts whispering through a barren landscape that had been silent for billions of years.

That sound, simple as it was, struck a chord deep within us. It reminded us that Mars is not a dead rock in the void—it is a world with its own weather, its own heartbeat of seismic tremors, its own rhythm of dust and wind.

InSight also detected marsquakes—subtle rumbles from beneath the surface that reveal the planet’s internal structure. These quakes tell us that Mars, though cold, is not entirely still. Its crust shifts, its mantle stirs faintly, and its heart still beats with the echoes of ancient fire.

The Challenge of Reaching Mars

Getting to Mars is hard—brutally hard. The distance from Earth varies between 55 and 400 million kilometers, depending on the planets’ positions. Every mission must launch during narrow windows when the alignment is favorable, a journey that takes between six and nine months.

Spacecraft must survive intense radiation, navigate with pinpoint precision, and enter Mars’s thin atmosphere at tremendous speed. The air is too thin to slow a spacecraft easily but thick enough to generate heat from friction. Landing safely is a delicate ballet of engineering.

NASA engineers call it “seven minutes of terror”—the time it takes for a probe to descend through the atmosphere, deploy parachutes, fire retrorockets, and (hopefully) touch down safely. Radio signals take 11 minutes to travel from Mars to Earth, so the entire landing must be automated.

Out of dozens of missions, nearly half have failed. Yet each success brings us closer to mastering the art of reaching—and eventually living on—this distant world.

The Human Dream of Mars

For generations, Mars has been the dream destination of explorers, writers, and visionaries. Wernher von Braun, the father of rocket science, imagined a fleet of ships traveling there in the 1950s. In the 21st century, entrepreneurs like Elon Musk have reignited that dream, envisioning human colonies on the Red Planet.

The motivation is more than curiosity. Mars offers humanity a chance to become a multi-planetary species—to ensure our survival beyond Earth’s fragile cradle. If we can live on Mars, we prove that life can adapt beyond its birthplace.

But the challenges are immense. Mars’s atmosphere is unbreathable, its radiation levels deadly, and its temperature hostile. Any colony would need airtight habitats, renewable energy, and a sustainable food supply. Water must be extracted from underground ice, and oxygen from the carbon dioxide-rich air.

Scientists and engineers are already testing technologies for terraforming—slowly altering Mars’s environment to make it more Earth-like. Though such a feat may take centuries, even small steps, like warming the atmosphere or thickening it enough to allow liquid water, could transform the planet into a second home for humanity.

The Robots That Paved the Way

Before humans ever set foot on Mars, robots became our eyes, ears, and hands on the red frontier. From the first flybys of Mariner 4 in 1965 to the landings of Viking, Pathfinder, Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, InSight, and Perseverance, each mission has extended our understanding of the planet.

These machines are more than metal—they are emissaries of our collective curiosity. The rovers that trundle across the Martian plains carry pieces of human ingenuity and emotion. Spirit and Opportunity survived far longer than expected, exploring craters and plains for years. When Opportunity finally went silent, people around the world mourned it as though it were a living being.

Curiosity continues to climb the slopes of Mount Sharp, analyzing rocks for signs of past habitability. Perseverance collects samples and even carries a small helicopter—Ingenuity—which achieved the first powered flight on another planet, a milestone that echoed humanity’s first flight on Earth.

Each rover leaves behind a trail of tracks in the dust—footprints of humanity’s presence on a world we have not yet walked upon.

The Red Frontier and Our Future

Mars is not only a scientific goal but a psychological one. It represents the eternal human drive to explore, to push beyond horizons. The same spirit that led ancient sailors to cross oceans now compels us to cross interplanetary space.

A future Mars colony would be humanity’s boldest experiment—testing whether we can build a new civilization under alien skies. The settlers who go there will face isolation, hardship, and the constant awareness that survival depends on fragile machinery and teamwork. Yet they will also carry the greatest adventure ever undertaken.

In time, their children might call Mars home. They will grow up beneath pink skies, with two small moons—Phobos and Deimos—drifting overhead. They will look up at Earth as a distant blue star and read in their history lessons about the ancestors who dared to reach across space to give life a second home.

The Moons of Mars

Phobos and Deimos, the two moons of Mars, are tiny and irregular, like captured asteroids. Phobos, the larger of the two, orbits so close to the planet that it rises and sets twice each Martian day. Deimos, smaller and farther away, drifts lazily across the sky like a pale pebble.

Phobos is doomed. It is gradually spiraling inward, pulled by Mars’s gravity. In 50 million years, it will either crash into the planet or break apart, forming a temporary ring around Mars—a reminder that even moons are mortal.

These small companions, though unremarkable compared to our Moon, are treasures for exploration. They could one day serve as waystations or sources of material for human missions to the Martian surface.

The Echo of Ancient Life

Perhaps the most haunting question Mars poses is whether life ever truly began there. Meteorites from Mars that have landed on Earth contain traces of organic molecules—carbon-based building blocks of life. They don’t prove life existed, but they hint that the chemistry of life is not unique to Earth.

Some scientists speculate that life might have originated on Mars and later spread to Earth via meteorites ejected by asteroid impacts—a concept known as panspermia. If true, then we are, in a sense, Martians ourselves.

Finding fossilized microbes or even active microbial life in underground aquifers on Mars would change everything. It would tell us that the universe is fertile, that life is not a miracle but a rule.

The Spirit of Discovery

Mars embodies the best of humanity—the courage to dream, to fail, and to try again. Every mission is a testament to our determination to reach beyond what seems possible. It is a scientific pursuit, yes, but also a deeply emotional one.

When a rover lands safely, the cheers that erupt in control rooms are not just for data—they are for the triumph of human spirit over distance, silence, and time.

We explore Mars not merely to find life, but to understand life—to see how fragile and precious it truly is.

The Red Reflection

In the end, Mars is more than a planet. It is a reflection of ourselves—a reminder that even in desolation, there is beauty; even in failure, there is hope. It shows us what could become of Earth if we do not cherish our own fragile atmosphere. And it reminds us that we are capable of extraordinary things when guided by curiosity and courage.

When future generations stand on the dusty plains of Mars and gaze up at the faint blue dot of Earth in their sky, they will feel what our ancestors felt when they looked at Mars from afar—a sense of wonder and belonging to something vast and mysterious.

The Red Frontier is not just out there—it is within us. It is the dream that drives us to reach for new worlds, to overcome limits, and to ensure that the flame of life continues to burn, wherever it may travel.

Mars awaits, silent and patient, a world of rust and memory, fire and frost. It has waited for billions of years for us to arrive. And now, as our machines roam its surface and our dreams draw ever nearer, the red planet stands as the next chapter in the human story—an unfinished page written in dust, waiting for our footprints to complete it.