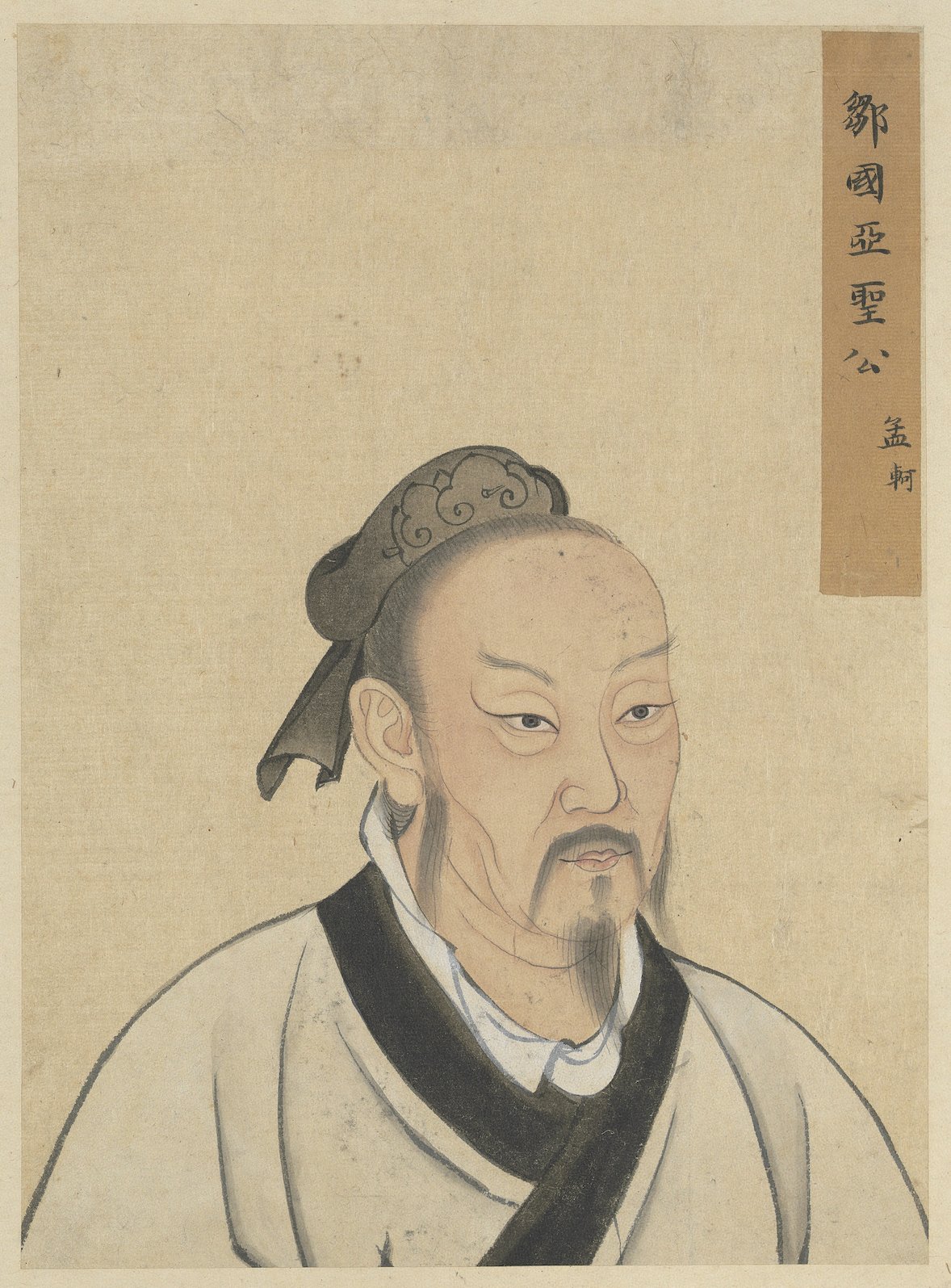

Mencius (c. 372–289 BCE) was a Chinese philosopher and a key figure in Confucianism, often regarded as the most significant follower of Confucius. Born Meng Ke in the state of Zou during the Warring States period, Mencius expanded on Confucian thought, emphasizing the inherent goodness of human nature and the importance of righteous governance. He argued that people are born with an innate sense of morality and that a just ruler must cultivate this virtue through benevolent leadership and moral example. Mencius’s ideas on the role of government, ethics, and education are captured in the collection of texts known as the Mencius. His philosophical contributions deeply influenced Chinese thought, particularly in shaping Confucian ideals regarding human nature, politics, and social responsibility. Mencius is celebrated for his belief in the potential for self-improvement and the ethical responsibilities of leaders and individuals.

Early Life

Mencius was born around 372 BCE in the small state of Zou, located in what is now modern-day Shandong Province. His personal name was Meng Ke (孟軻), and he hailed from a family that valued education and moral cultivation. Little is known about his father, who died when Mencius was young, leaving him to be raised by his mother, Zhang (仉氏). Mencius’ mother has become an emblematic figure in Chinese culture, revered for her dedication to her son’s education and moral upbringing.

The story of Mencius’ mother moving her family three times to find a suitable environment for her son’s upbringing is legendary in Chinese folklore. Initially, the family lived near a cemetery, but Zhang moved after noticing Mencius imitating funeral rites in his play. Their next home was near a marketplace, but Zhang again relocated when she observed Mencius mimicking the traders’ haggling. Finally, they settled near a school, where Mencius began to imitate the scholars and their rituals. This story highlights Zhang’s commitment to providing an environment conducive to her son’s moral and intellectual growth. Mencius himself later emphasized the importance of environment in shaping character, a principle that was undoubtedly influenced by his early experiences.

Philosophical Background

To fully appreciate Mencius’ contributions, it is essential to understand the broader philosophical landscape of his time. Mencius lived during the Warring States period, a time of political fragmentation and intellectual flourishing. This era saw the rise of various philosophical schools, each offering different solutions to the moral and political chaos of the time.

Confucianism, founded by Confucius (Kongzi, 551–479 BCE), was one of the leading schools of thought. Confucius emphasized the importance of ritual (li), benevolence (ren), and the cultivation of virtuous character as the foundation of a harmonious society. However, Confucianism faced competition from other philosophical schools, such as Daoism, which advocated for a return to natural simplicity, and Legalism, which promoted strict laws and harsh punishments to maintain order.

Mencius entered this intellectual milieu as a staunch defender and elaborator of Confucian thought. He sought to deepen and expand upon Confucius’ teachings, particularly in response to the challenges posed by rival schools of thought. His most significant philosophical contribution was his theory of human nature, which he used to argue for the inherent goodness of human beings and the potential for moral cultivation.

Teachings and Philosophy

Human Nature (Ren Xing)

One of Mencius’ most famous and influential ideas is his belief in the innate goodness of human nature. He argued that all humans are born with the capacity for benevolence (ren), righteousness (yi), propriety (li), and wisdom (zhi). These four virtues, which Mencius referred to as the “Four Beginnings” or “Four Sprouts” (si duan), are the foundation of moral development.

Mencius illustrated this idea with the famous example of a child falling into a well. He argued that anyone witnessing such an event would instinctively feel a sense of alarm and compassion, regardless of personal interest. This instinctive reaction, Mencius claimed, is evidence of the innate goodness of human nature. The Four Beginnings, while present in all people, require cultivation and refinement through education, self-reflection, and proper moral guidance.

Mencius’ theory of human nature stood in contrast to the views of other philosophers of his time, particularly the Legalist thinker Xunzi (荀子), who argued that human nature is inherently selfish and evil, requiring strict external control through laws and institutions. Mencius, on the other hand, believed that moral cultivation and virtuous leadership could nurture and bring out the best in people, leading to a harmonious and just society.

The Role of Government and Leadership

Mencius extended his views on human nature to his political philosophy, arguing that a just and benevolent government is essential for the moral and material well-being of the people. He believed that rulers should govern with virtue and compassion, acting as moral exemplars for their subjects. Mencius often emphasized the concept of the “Mandate of Heaven” (Tianming), which he interpreted as a moral standard that rulers must uphold to maintain their legitimacy. If a ruler fails to govern justly and loses the people’s trust, he argued, the Mandate of Heaven could be revoked, justifying rebellion or the removal of the ruler.

Mencius was a strong advocate for the welfare of the common people. He believed that the primary responsibility of a ruler was to ensure the well-being of his subjects by providing for their basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter. He famously stated that “the people are the most important element in a nation; the spirits of the land and grain come next; the ruler is the least important.” This emphasis on the people’s welfare was a radical departure from the more authoritarian views of other philosophers, particularly the Legalists, who prioritized state power and control over individual well-being.

Mencius also emphasized the importance of education and moral development for both rulers and subjects. He believed that a well-educated and morally cultivated population was essential for a stable and prosperous society. To this end, he advocated for the establishment of schools and the promotion of Confucian values as the foundation of education.

The Four Beginnings and Moral Cultivation

Mencius’ concept of the Four Beginnings is central to his philosophy of moral cultivation. He believed that these innate virtues—benevolence, righteousness, propriety, and wisdom—were like seeds that could grow and flourish if properly nurtured. The process of moral cultivation, according to Mencius, involves self-reflection, learning from the examples of virtuous people, and practicing ethical behavior in daily life.

Mencius also introduced the idea of “extending one’s heart” (tui xin), which involves expanding one’s natural feelings of compassion and empathy beyond one’s immediate family and social circle to encompass all of humanity. This process of moral expansion, he argued, leads to the development of universal benevolence and the cultivation of a truly virtuous character.

Mencius’ emphasis on moral cultivation and self-improvement resonated with many Confucian scholars and became a central theme in later Confucian thought. His belief in the potential for moral growth and the importance of nurturing one’s innate virtues has had a lasting impact on East Asian ethics and education.

Political Activity

Mencius was not only a philosopher but also an active political figure who sought to apply his ideas in the real world. Like Confucius before him, Mencius traveled across various states, offering his services as an advisor to rulers and advocating for his vision of benevolent governance.

During his travels, Mencius encountered several rulers, including King Hui of Liang (梁惠王) and King Xuan of Qi (齊宣王). He sought to persuade them to adopt Confucian principles of governance, emphasizing the importance of ruling with virtue and compassion. Mencius argued that a ruler who governed justly and cared for the welfare of his people would gain their loyalty and support, leading to a strong and stable state.

However, Mencius’ political career was not without challenges. The Warring States period was a time of intense competition and conflict between rival states, and many rulers were more interested in military conquest and power than in moral governance. Despite his best efforts, Mencius often found his advice ignored or rejected by rulers who prioritized short-term gains over long-term moral principles.

One of Mencius’ most famous encounters was with King Xuan of Qi, who was interested in hearing Mencius’ views but ultimately found them impractical for the turbulent political climate of the time. Mencius urged the king to reduce taxes, provide for the people’s welfare, and govern with compassion, but the king was reluctant to implement these reforms. This encounter highlights the tension between Mencius’ idealism and the harsh realities of the Warring States period.

Despite these setbacks, Mencius remained committed to his principles and continued to advocate for benevolent governance. He believed that even if his ideas were not immediately adopted, they would eventually gain acceptance as people recognized the long-term benefits of virtuous leadership.

Major Works

The Mencius, also known as the Mengzi, is the primary text that records Mencius’ teachings and dialogues. The text is organized into seven books, each containing a series of conversations and debates between Mencius and various rulers, scholars, and other figures. The Mencius is written in a dialogic style, similar to the Analects of Confucius, and is considered one of the “Four Books” (Sishu) that form the core of Confucian education.

The Mencius covers a wide range of topics, including human nature, moral cultivation, government, and education. One of the central themes of the text is the idea of “extending one’s heart” (tui xin), which is closely linked to the Four Beginnings. Mencius repeatedly emphasizes that human nature, though inherently good, requires careful cultivation. Through his conversations and debates in the Mencius, he provides insights on how individuals and rulers alike can nurture and expand their innate moral capacities to create a harmonious society.

Some of the most notable passages in the Mencius include:

- The Child and the Well: As previously mentioned, this is one of Mencius’ most famous illustrations. He argues that the instinctive reaction to save a child about to fall into a well is evidence of the inherent goodness of human nature, which manifests as compassion.

- The Ox Mountain Parable: Mencius uses the story of Ox Mountain, once lush but now barren due to continuous deforestation, as a metaphor for human nature. Just as the mountain’s original beauty was destroyed by external forces, human nature can be corrupted by negative influences. However, Mencius argues that just as the mountain could regain its beauty if left to regenerate, human nature can be restored through proper moral cultivation.

- Debates on Governance: The Mencius records various debates between Mencius and the rulers he sought to advise. In these dialogues, Mencius often challenges the rulers on their policies, advocating for the well-being of the people and the importance of moral governance. For example, in his discussions with King Hui of Liang, Mencius argues that a ruler who is just and benevolent will naturally gain the allegiance of his people, as opposed to one who rules through fear and coercion.

- The Doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven: Mencius elaborates on the Confucian concept of the Mandate of Heaven, asserting that the moral legitimacy of a ruler is contingent on his virtue and ability to care for the people. If a ruler loses the Mandate of Heaven by failing to govern justly, it is not only the right but also the duty of the people to overthrow him. This idea became a powerful justification for rebellion against tyrannical rulers in Chinese history.

The Mencius is more than just a philosophical text; it is a record of Mencius’ intellectual and moral struggles as he sought to apply his ideals in a world that often seemed indifferent or hostile to them. His dialogues reflect his deep conviction in the possibility of moral progress, both for individuals and for society as a whole.

Legacy and Influence

Mencius’ influence on Chinese thought cannot be overstated. While he did not achieve widespread political success during his lifetime, his ideas eventually gained prominence and became a central component of Confucian philosophy. The Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), which established Confucianism as the state ideology, recognized Mencius as one of the most important interpreters of Confucius, and his works were included in the Confucian canon.

During the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), the Neo-Confucian movement, led by scholars like Zhu Xi (1130–1200 CE), further elevated Mencius’ status. Zhu Xi compiled the Four Books, which included the Mencius, the Analects, the Great Learning, and the Doctrine of the Mean. These texts became the core curriculum for the civil service examinations, which were the primary means of entry into the Chinese bureaucracy for over a thousand years. As a result, Mencius’ ideas became deeply ingrained in Chinese political and educational institutions.

Mencius’ emphasis on the innate goodness of human nature and the importance of moral cultivation has had a lasting impact on East Asian cultures, influencing not only China but also Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. His ideas have been integrated into various aspects of these societies, including their educational systems, ethical frameworks, and political philosophies.

In Korea, Mencius’ teachings were highly regarded by the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), which adopted Neo-Confucianism as its state ideology. Korean scholars like Yi Hwang (1501–1570) and Yi I (1536–1584) drew heavily on Mencius’ ideas in their own writings, further disseminating his influence across the Korean Peninsula.

In Japan, Mencius’ philosophy was studied by Confucian scholars during the Edo period (1603–1868) and contributed to the development of Japanese ethical and political thought. His ideas on moral cultivation and the role of the ruler in promoting the welfare of the people resonated with Japanese thinkers who sought to reconcile Confucianism with indigenous Japanese values.

Mencius in Modern Times

In the modern era, Mencius’ ideas continue to be relevant as scholars and political leaders grapple with issues of ethics, governance, and human rights. His belief in the inherent goodness of human nature and the potential for moral progress has inspired contemporary discussions on human rights and social justice. In particular, Mencius’ emphasis on the importance of benevolent leadership and the welfare of the people has been invoked in debates about the role of government in modern society.

In the 20th century, Chinese intellectuals such as Liang Qichao (1873–1929) and Hu Shi (1891–1962) engaged with Mencius’ ideas as they sought to modernize China and address the challenges of imperialism and internal strife. While some criticized Mencius for his perceived idealism and lack of practical solutions to China’s problems, others found in his philosophy a source of inspiration for reform and moral renewal.

Mencius’ influence can also be seen in the modern emphasis on education in East Asia. His belief in the importance of moral cultivation through education has contributed to the strong educational traditions in China, Korea, and Japan, where Confucian values continue to play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward learning and personal development.

In the West, Mencius’ ideas have been studied by scholars of Chinese philosophy and have been compared with Western philosophical traditions. Some have noted similarities between Mencius’ views on human nature and those of philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who also believed in the inherent goodness of humans. Others have explored the potential for dialogue between Mencius’ Confucianism and modern ethical theories, particularly in the context of global discussions on human rights and the common good.

Comparative Analysis with Western Philosophy

Mencius’ philosophy offers intriguing parallels and contrasts with various Western philosophical traditions. His belief in the innate goodness of human nature, for instance, finds some resonance with the ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau, who famously declared that “man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,” suggesting that society corrupts an originally pure human nature. However, while Rousseau saw the solution in returning to a more natural state, Mencius emphasized the importance of cultivating one’s moral potential within society, aligning more closely with the Confucian ideal of moral development through social engagement.

Mencius’ ideas also invite comparison with Aristotelian ethics. Both Mencius and Aristotle emphasize the importance of cultivating virtues through practice and education, though Mencius places a stronger emphasis on the inherent potential for virtue in all people, whereas Aristotle is more concerned with the role of rationality and habituation in the development of moral character.

Furthermore, Mencius’ political philosophy, with its emphasis on benevolent governance and the welfare of the people, can be compared with the social contract theories of Western philosophers like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. While Hobbes viewed human beings as naturally selfish and in need of a strong, authoritarian government to maintain order, Mencius believed that people are naturally inclined toward goodness and that rulers should govern by moral example rather than by force.

Mencius’ advocacy for the welfare of the people also resonates with modern democratic principles, particularly the idea that the legitimacy of a government depends on its ability to serve the interests of the people. However, unlike modern democratic theorists who argue for the participation of all citizens in government, Mencius placed more emphasis on the moral character of rulers and the importance of virtuous leadership.