Far beyond the shimmering orbits of the major planets, past the realm of gas giants and icy moons, there lies a small, distant world cloaked in twilight. Pluto, once celebrated as the ninth planet of our Solar System, has become a symbol of both scientific humility and human affection—a tiny world that captured the imagination of generations and refused to vanish quietly into obscurity.

Discovered in 1930, Pluto was long hailed as the mysterious frontier of our cosmic family—the lonely guardian of the outer darkness. Children memorized its name in planetary lists, astronomers debated its origins, and poets saw in it the cold heart of the unknown. Then, in 2006, it was officially demoted to the status of a “dwarf planet,” a reclassification that sparked outrage, grief, and even humor.

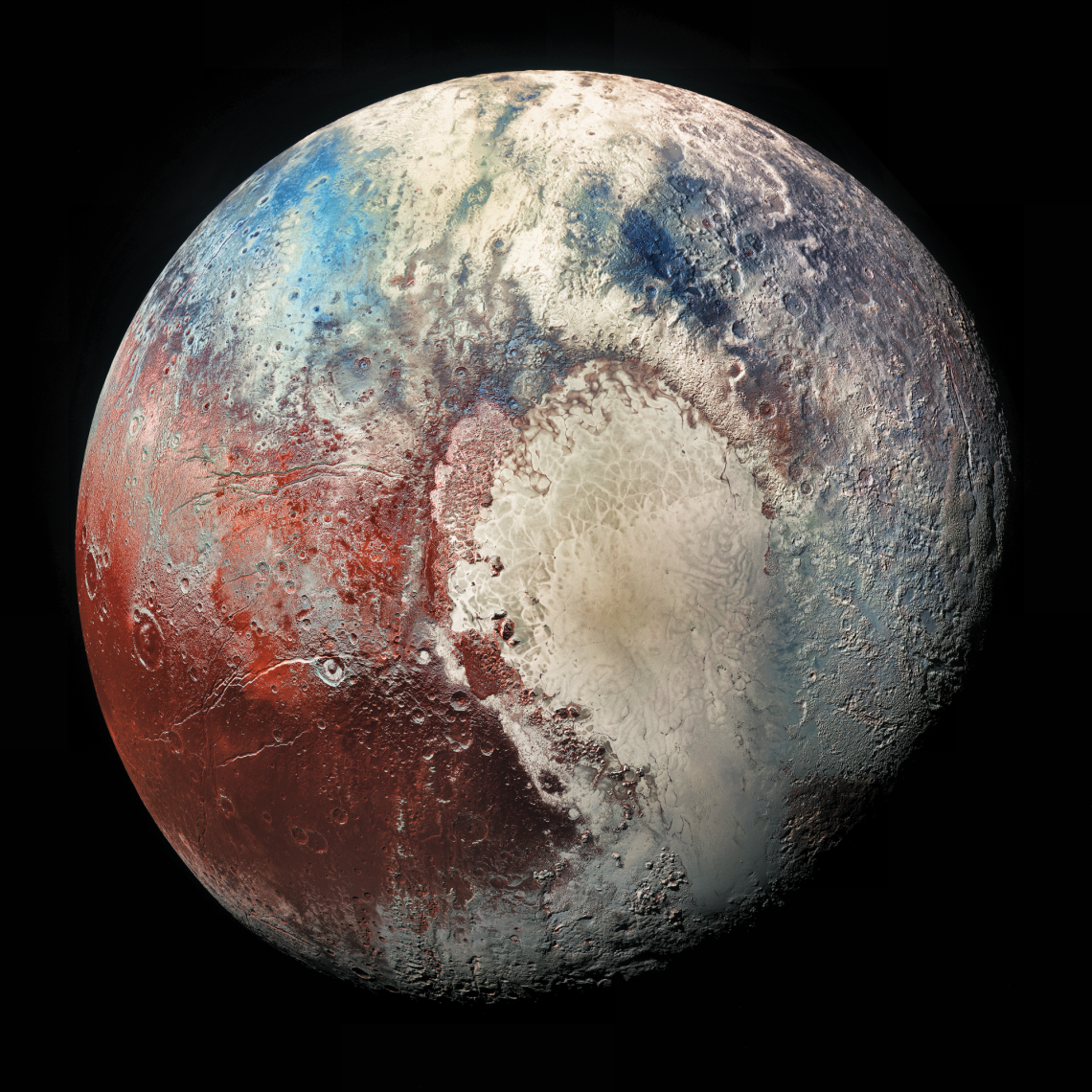

But Pluto’s story did not end there. With the arrival of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft in 2015, humanity glimpsed this remote world up close for the first time—and discovered something astonishing. Pluto, it turned out, was not a barren rock, but a vibrant, dynamic world of ice mountains, frozen plains, and blue hazy skies. It was not the end of its story, but the beginning of a new one.

Pluto may have lost its title, but it never lost our hearts.

The Search for the Ninth Planet

Pluto’s discovery was born out of obsession, persistence, and the human need to complete patterns. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, astronomers noticed irregularities in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune that suggested the presence of another massive planet beyond them. They called it “Planet X.”

The search consumed the imagination of Percival Lowell, a wealthy American astronomer who had already gained fame for claiming to see canals on Mars. From his observatory in Arizona, Lowell spent years scanning the skies, convinced that a hidden planet was tugging at the outer giants with its gravity. Though he died in 1916 without success, his observatory continued his quest.

Fourteen years later, a young Kansas farm boy named Clyde Tombaugh was hired to continue Lowell’s work. With tireless patience, Tombaugh compared pairs of photographic plates of the same star fields, looking for any faint object that shifted position. On February 18, 1930, he found it—a tiny moving dot against the fixed stars.

Pluto had been discovered. The world rejoiced.

Naming a New World

The new planet needed a name. Suggestions poured in from around the world—Minerva, Cronus, Atlas—but the winning name came from an unexpected source: an eleven-year-old girl in England named Venetia Burney. Fascinated by mythology, she suggested “Pluto,” after the Roman god of the underworld, ruler of the cold, dark realm below.

The name was perfect. It honored both the planet’s dim, distant nature and the initials of Percival Lowell—PL. When the name was announced, it resonated across cultures and generations. The god of the underworld had found his home among the stars.

Pluto soon took root in the popular imagination. It was the mysterious planet of the frontier, the embodiment of the unknown, and a symbol of human curiosity reaching its limits.

The Mysterious World Beyond Neptune

In the decades following its discovery, Pluto remained a puzzle. Astronomers could barely glimpse it, and its faint light revealed little. At nearly 6 billion kilometers from the Sun, it was so distant that even the largest telescopes showed only a point of light.

Initial estimates suggested that Pluto was larger than Earth’s Moon, perhaps even rivaling Mars. But as technology improved, its estimated size kept shrinking. By the late 20th century, it became clear that Pluto was much smaller than originally thought—only about 2,376 kilometers across, or roughly one-sixth the width of Earth.

This was no mighty planet, but a world of modest size. Its orbit, too, was strange—highly elliptical and tilted at a 17-degree angle to the plane of the Solar System. Sometimes, Pluto even came closer to the Sun than Neptune. It was as if the tiny world refused to follow the rules of the planetary order.

Pluto was already an oddball, but even greater surprises were waiting.

The Discovery of Charon: Pluto’s Giant Companion

In 1978, American astronomer James Christy was studying photographic plates of Pluto when he noticed something peculiar. The planet seemed to bulge and elongate in a regular pattern, as if something were orbiting it. Christy had discovered Pluto’s largest moon, Charon.

Charon was not a mere satellite—it was enormous, nearly half the size of Pluto itself. Together, the two formed what some astronomers call a “binary planet” system, orbiting a common center of gravity that lies between them in space.

Charon transformed our understanding of Pluto. Its discovery allowed astronomers to measure Pluto’s mass accurately for the first time—revealing that it was far smaller than expected, only about 0.2% the mass of Earth. This realization set in motion decades of debate about whether Pluto truly deserved its planetary status.

But Charon also made Pluto more fascinating. It was as if this distant world had a companion—a silent partner sharing its lonely journey at the edge of the Sun’s reach.

The Icy Heart of the Kuiper Belt

In the 1990s, astronomers began discovering other icy bodies beyond Neptune—small, frozen worlds orbiting in a vast region known as the Kuiper Belt. Pluto was not alone. There were thousands of these icy remnants, relics from the early Solar System.

The Kuiper Belt changed everything. It revealed that Pluto was not the last planet of the Solar System, but the first known member of a whole new class of objects. Some of these newly discovered bodies, like Eris, were nearly the same size as Pluto—or even slightly larger.

This discovery forced a difficult question: if Pluto was a planet, then shouldn’t Eris and others like it be planets too? And if not, was Pluto truly special—or simply one among many icy dwarfs drifting in the outer darkness?

The Great Demotion

In August 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) convened in Prague to decide Pluto’s fate. After intense debate, they redefined what it means to be a planet. According to the new definition, a planet must meet three criteria:

- It must orbit the Sun.

- It must be massive enough for its gravity to make it roughly spherical.

- It must have “cleared its orbit” of other debris.

Pluto satisfied the first two—but not the third. It shares its orbital neighborhood with many Kuiper Belt objects. Thus, Pluto was officially reclassified as a dwarf planet.

The decision was logical from a scientific standpoint, but emotionally devastating. Pluto had been part of our lives for 76 years. The public reaction was immediate and fierce. Headlines screamed “Pluto Demoted!” Children’s textbooks became outdated overnight. Some scientists protested the decision, arguing that it was premature and arbitrary.

In classrooms, protests took the form of doodles and chants: Bring back Pluto!

A Planet by Any Other Name

To many, Pluto will always be the ninth planet. The debate continues even today, with astronomers, philosophers, and the public divided over whether the IAU’s definition makes sense. After all, the term “planet” is a human concept—a label, not a law of nature.

In the years since its demotion, some planetary scientists have argued for restoring Pluto’s status, suggesting that the “cleared orbit” rule is too restrictive. Even Earth shares its orbit with countless asteroids and debris, they note.

Regardless of its official title, Pluto remains every bit as complex and captivating as the larger planets. Its reclassification has not diminished its mystery; if anything, it has made it more compelling.

The controversy over Pluto’s identity reflects something profound about humanity: our tendency to project emotion onto the cosmos. We didn’t just lose a planet—we lost a piece of our story.

The Journey of New Horizons

For decades, Pluto remained a distant blur—until NASA launched New Horizons in 2006, the same year it was demoted. The timing was poetic: as Pluto lost its planetary crown, a spacecraft was already en route to restore its glory in another way.

Traveling at nearly 58,000 kilometers per hour, New Horizons became one of the fastest spacecraft ever launched. It took more than nine years to reach its destination. As it sped toward Pluto, the anticipation built to a global crescendo. For the first time in human history, we would see this enigmatic world up close.

On July 14, 2015, New Horizons made its historic flyby. The images it sent back changed everything.

Pluto was no longer a point of light—it was a world. A real, living world, with mountains, valleys, plains, and a beating geological heart.

The Heart of Pluto

The most striking feature revealed by New Horizons was a vast, heart-shaped plain near Pluto’s equator, later named Tombaugh Regio, in honor of its discoverer. One half of the heart, called Sputnik Planitia, is a frozen basin filled with nitrogen ice. It gleams like polished marble under the distant sunlight.

This heart became the symbol of Pluto’s resilience—a literal reminder that the “lost planet” still had heart, both scientifically and metaphorically. But beyond its poetic beauty, Sputnik Planitia also held clues to Pluto’s dynamic nature.

The smooth, uncratered surface suggested that the ice plain is relatively young, geologically speaking. Convection cells of slowly moving nitrogen ice—driven by heat from Pluto’s interior—are continually renewing the surface. This means Pluto is still active, long after it should have frozen solid.

Underneath that icy heart, scientists suspect an ocean of liquid water may still exist, insulated by layers of rock and ice. A hidden ocean—on a world once thought dead—rewrote our understanding of small planets.

Mountains of Ice and Skies of Blue

Pluto’s landscape astonished scientists. Towering mountains of water ice rise as high as 4,000 meters, their peaks coated with frozen nitrogen and methane. Water ice on Pluto is so cold that it behaves like stone. The mountains stand like frozen fortresses under a dim Sun, their slopes bathed in a faint reddish light reflected from the surface.

Above them, a thin but dynamic atmosphere rises hundreds of kilometers high. New Horizons revealed delicate layers of haze glowing blue in the sunlight. This haze is formed by sunlight breaking apart methane molecules, which then recombine into complex hydrocarbons called tholins—organic compounds that settle onto the surface, giving Pluto its reddish hue.

That blue haze—soft, ethereal, and unexpected—gave Pluto a touch of familiar beauty. In the deep cold of space, beneath a distant Sun, there exists a sky that glows with a shade of blue.

The Dance of Pluto and Charon

Pluto and Charon are forever locked in a cosmic waltz. Each shows the same face to the other, a phenomenon known as tidal locking. From Pluto’s surface, Charon never rises or sets—it hangs fixed in the same spot in the sky, always watching.

Their gravitational embrace is so strong that it affects Pluto’s shape and even its interior. The two worlds orbit their common center of mass every 6.4 Earth days, like dancers circling a point in empty space.

Charon itself is a world of wonders—its surface marked by massive chasms and canyons far deeper than the Grand Canyon. Some of these fractures may have formed as Charon’s interior froze and expanded, cracking its crust apart.

Together, Pluto and Charon form one of the most intriguing binary systems in the Solar System—a reminder that companionship can exist even in the loneliest corners of space.

The Family of Pluto

Pluto is not entirely alone in its orbit. It is accompanied by four smaller moons—Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra—each discovered between 2005 and 2012. These moons orbit in a complex, resonant dance, their paths stabilized by the gravitational influence of both Pluto and Charon.

Nix and Hydra, in particular, are irregularly shaped and surprisingly bright, reflecting more sunlight than expected. Their chaotic rotations—tumbling unpredictably in space—suggest that the gravitational interactions among the moons are intricate and ongoing.

This miniature moon system makes Pluto even more planet-like, with its own little solar system circling in frozen harmony.

The Secrets Beneath the Surface

Perhaps the greatest surprise of New Horizons was the discovery that Pluto is still geologically active. Despite being small and far from the Sun, its surface shows signs of movement, renewal, and internal heat.

The source of this heat remains mysterious. Some scientists believe it comes from the slow decay of radioactive elements in Pluto’s rocky core. Others propose that Pluto retains leftover heat from its formation or that tidal interactions with Charon once stirred its interior.

Whatever the cause, Pluto’s vitality challenges the old assumption that small worlds are dead worlds. Beneath its frozen crust may lie an ocean of liquid water—kept from freezing by pressure and antifreeze-like chemicals.

If that ocean exists, it raises profound questions. Could it harbor life, perhaps microbial organisms surviving in the dark, under kilometers of ice? The possibility is remote but tantalizing.

The Color of Cold

Pluto’s colors are not uniform. Some regions are pale and icy; others are tinted orange, red, or brown. These variations come from the chemical reactions between sunlight and the surface ices, which create tholins—complex organic molecules that darken with exposure.

These tholins are also found on Titan, Neptune’s moon Triton, and even comets—suggesting a shared chemistry among distant, icy bodies. The reddish hues of Pluto’s surface may therefore tell an ancient story about the chemistry of the early Solar System, when complex organics first formed in the cold.

In this way, Pluto serves as a time capsule—a frozen memory of the materials that once drifted through the newborn Solar System, waiting to become planets, moons, and eventually, life.

The Coldest Sunlight

At Pluto’s distance, the Sun is only a bright star in the sky, 1,600 times fainter than it appears from Earth. Yet that faint sunlight still gives rise to a day and night cycle, casting long shadows across icy mountains and illuminating the heart-shaped plains.

A “day” on Pluto lasts about 6.4 Earth days—the same as its rotation period. Its seasons last for decades, and its orbit carries it from 4.4 to 7.4 billion kilometers from the Sun. As it moves closer, parts of its frozen surface sublimate, forming a thin atmosphere. As it moves farther away, that atmosphere freezes and falls as snow.

Pluto breathes in frozen rhythm—a world whose seasons unfold over human lifetimes.

The Emotional Legacy of a Lost Planet

Why do people care so deeply about Pluto? After all, it’s a frozen ball of rock and ice, smaller than our Moon and invisible to the naked eye. And yet, its story resonates.

Perhaps it’s because Pluto represents something deeply human—the outsider, the underdog, the misunderstood soul that still shines brightly. It reminds us that small does not mean insignificant. That distance does not erase belonging.

When New Horizons sent back that first close-up photo—the heart-shaped region gleaming in the darkness—it felt as though Pluto was smiling back at us, saying: You may have forgotten me, but I never forgot you.

It was one of the most emotional moments in modern astronomy, a reminder that science is not just about data and classification, but about connection.

Beyond Pluto: The Frontier Continues

After its encounter, New Horizons continued deeper into the Kuiper Belt, flying past another object known as Arrokoth (previously nicknamed Ultima Thule) in 2019. This contact binary—two icy lobes fused together—offered a glimpse into the building blocks of planets.

Through Pluto and its neighbors, scientists are piecing together the story of how the Solar System formed—how small icy bodies like these merged, collided, and evolved over billions of years. Pluto is not just a footnote in that story; it is a crucial chapter.

The Meaning of Pluto

In many ways, Pluto embodies the dual nature of discovery. It is a scientific object—measurable, classifiable, analyzed with data. But it is also a symbol, a reminder of how deeply humans invest emotion into exploration.

Pluto teaches us that the universe is not bound by our definitions. It doesn’t care what we call a “planet.” It simply exists, endlessly complex and endlessly surprising.

The debates about Pluto’s status reveal as much about us as they do about the cosmos. We seek order, but the universe resists simplicity. We crave belonging, but the cosmos is vast and indifferent. Yet we keep exploring, because to understand the unknown is to understand ourselves.

The Planet That Refused to Be Forgotten

Pluto may no longer hold the title of the ninth planet, but in every other way, it remains part of our Solar System’s heart. It is the lost world that found a way to return, the silent wanderer that spoke volumes through a single image of light and ice.

Its demotion did not diminish it—it transformed it. Pluto has become a symbol of resilience, of the enduring power of curiosity, and of the beauty hidden in the smallest corners of creation.

Every time we look at that heart-shaped plain, we are reminded that wonder cannot be defined by categories.

Pluto still orbits, still gleams faintly in the Sun’s farthest light, and still carries its secrets through the endless dark.

The Eternal Journey

As the years pass, Pluto continues its long journey around the Sun—a single orbit lasting 248 Earth years. It will return to its current position in the year 2178, long after all who first debated its status are gone. Yet it will still be there, faithful as ever, gliding through the quiet beyond Neptune.

Perhaps one day, new explorers—human or robotic—will return to Pluto’s skies, to study its mountains and oceans, to listen for the whispers of its atmosphere. And when they do, they will not just be studying a distant world—they will be paying homage to a legend.

Pluto is proof that discovery is not about power or prestige, but about wonder. That even the smallest worlds can inspire the greatest stories.

And so, at the far edge of sunlight, where day fades into eternal night, Pluto continues to shine—a tiny, stubborn flame against the cosmic cold.

The lost planet that refused to be forgotten.