In the vast, wind-scoured heart of Central Asia, a quiet revolution in archaeological understanding is underway. Beneath the raw and timeless landscape of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, a team of researchers is peeling back the layers of deep prehistory, revealing stories buried in stone and sand for over ten thousand years. It is here, in a remote corner known as Tsakhiurtyn Hundi—more evocatively dubbed Flint Valley—that humanity’s distant footsteps are beginning to echo more clearly than ever before.

About 700 kilometers south of Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, nestled within the rocky embrace of the Arts Bogdyn Nuruu massif, Flint Valley might seem, at first glance, like just another lonely outpost in a sprawling and ancient land. But for archaeologists, the valley is a living archive, a natural repository of ancient life, industry, and ingenuity. It was at the turn of the 21st century that a joint expedition of Mongolian, Russian, and American scientists first began to suspect the true significance of this place. Scattered across the valley floor were thousands of chipped stone fragments—flakes, blades, cores—testimony to an era when human survival depended on the subtle artistry of stone toolmaking. The valley takes its name from the abundance of flint—a critical raw material that prehistoric people transformed into knives, scrapers, arrowheads, and more.

Despite the valley’s obvious importance, research at the site had, until recently, been surprisingly limited. Much of the knowledge of Mongolia’s prehistory still rests on scattered surveys and the occasional excavation. But a new chapter began to unfold thanks to the dedicated work of Dr. Przemysław Bobrowski and his colleagues, whose project, funded by the National Science Centre of Poland, has cast fresh light on this enigmatic region. Their mission? To untangle the complex history of human occupation in and around Tsakhiurtyn Hundi over the last several hundred thousand years, through environmental reconstruction, radiocarbon dating, and material culture analysis.

The task began with old-fashioned legwork: an exhaustive survey of the surrounding landscape. Teams scanned the ground for telltale signs of habitation—flake scatters, hearths, and pottery shards. What they found were not isolated occurrences, but a network of sites clustered around the shores of ancient paleolakes—long-vanished bodies of water that once dotted the desert’s arid expanse. These lakes, some located several kilometers south of the Arts Bogdyn Nuruu massif, once served as magnets for human life, drawing hunter-gatherer groups who depended on water and game.

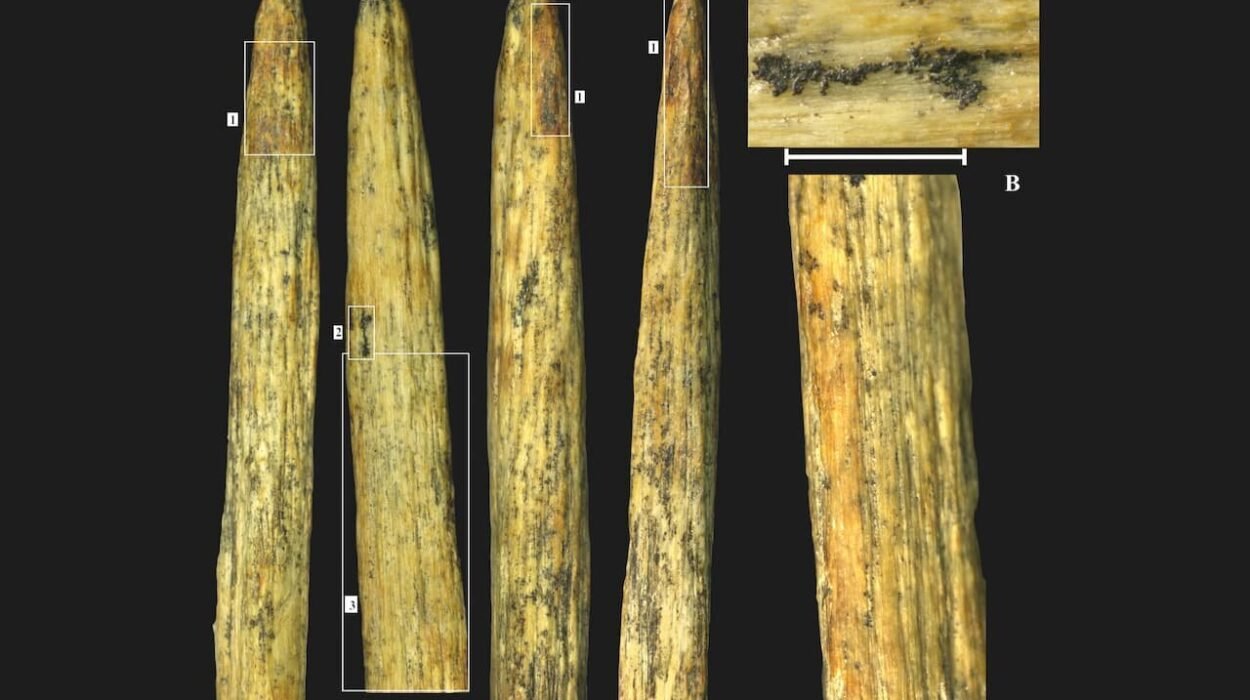

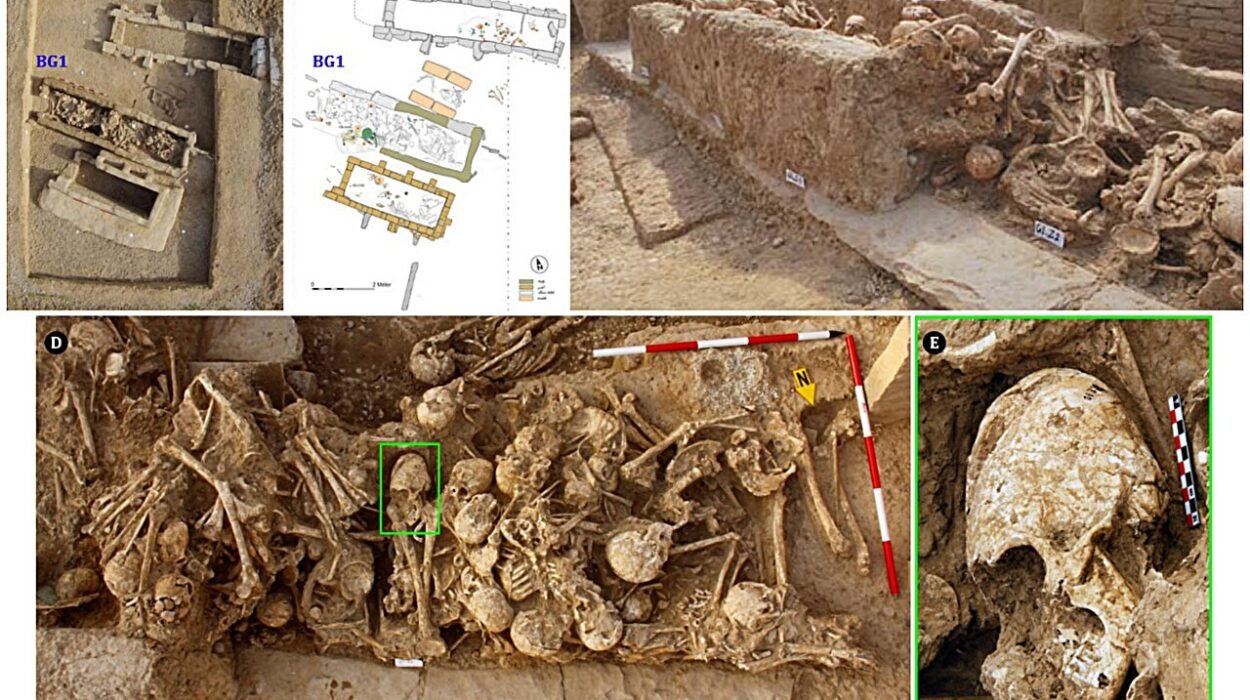

Among the paleolakes studied, one stood out: Baruun Khuree, known in the team’s records as Lake V. It became the focal point of their excavation campaign and the heart of one of the most surprising discoveries in recent Mongolian archaeology. At three different sites along the former lakeshore—FV 133, FV 134A, and FV 139—the team unearthed a remarkable array of artifacts: chipped stone tools, pieces of pottery, and, most curiously, fragments of ostrich eggshells, some shaped into beads and pendants.

The presence of ostrich eggshells in Mongolia may seem improbable today, but it is in fact a key indicator of a once very different ecological reality. The species in question, Struthio anderssoni, or the East Asian ostrich, roamed China and Mongolia during the Pleistocene and early Holocene. These flightless giants vanished from the region long ago, but their durable eggshells, resistant to the ravages of time, remain. To archaeologists, they are more than curiosities. They represent symbolic behavior, personal adornment, and even possibly trade or long-distance movement.

Even more important than the artifacts themselves were the results of the radiocarbon dating. Eleven new dates were secured from organic material at the Baruun Khuree sites. The data revealed two distinct periods of human occupation: an older horizon around 11,251–11,196 calibrated years before present (cal BP), and a younger phase dated to 10,620–10,535 cal BP. This firmly places these occupations within the very beginning of the Holocene epoch, the warm period following the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice sheets retreated and humans began to spread into new and more hospitable environments.

Such dates may appear, at first, like dry data points. But they carry profound implications. These Baruun Khuree sites now represent some of the earliest securely dated evidence for Holocene hunter-gatherers in the Mongolian Gobi. Long thought to be a marginal and sparsely inhabited environment, the desert is revealing itself as a place of continuity, adaptation, and resilience. Early humans were not merely surviving here—they were living, creating, and innovating.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the presence of pottery. Pottery is often associated with the Neolithic, with settled societies, agriculture, and food storage. In Mongolia, where the archaeological record of early ceramics is limited and scattered, the general consensus had placed the arrival of pottery around 9,600 cal BP. But the Baruun Khuree ceramics, found directly in hearth contexts associated with the older radiocarbon dates, upend this timeline completely. At nearly 11,200 years old, they are almost 2,000 years older than previously known Mongolian examples.

This shifts the narrative. Pottery did not trickle into Mongolia from agricultural centers over millennia; it arrived early, possibly through cultural exchange, migration, or parallel innovation. Intriguingly, these early Mongolian ceramics align chronologically with some of the earliest pottery traditions in northern China. While not identical in form or composition, the comparison suggests broader regional networks of knowledge and interaction during the terminal Pleistocene and early Holocene.

The Baruun Khuree pottery itself is distinctive. Typically gray to reddish in color, with a thickness of just 7–8 millimeters, it differs from later, better-known Mongolian ceramics. Its presence raises tantalizing questions. Who made it? Was it shaped by semi-nomadic groups who adopted the technology from neighbors, or by local populations experimenting with new ways to cook and store food? The answers remain elusive, but Dr. Bobrowski’s team is continuing detailed compositional and typological analysis to probe these mysteries further.

Equally fascinating is the discovery of ostrich eggshell jewelry. Beads and pendants fashioned from these fragments show a level of craftsmanship and aesthetic sense that speaks to more than utility. These objects tell of social signaling, identity, perhaps even spiritual beliefs. They are reminders that prehistoric life was not only about survival but also about meaning—about adornment, beauty, and expression.

In many ways, the Tsakhiurtyn Hundi project underscores how much remains to be discovered in the archaeology of Mongolia and Central Asia more broadly. While neighboring regions like China, Siberia, and the Eurasian Steppe have received considerable attention in the study of human prehistory, Mongolia has remained something of a blind spot—a vast land rich in sites, yet poor in detailed excavations and chronologically secure findings.

That is beginning to change. The work of Dr. Bobrowski and his colleagues illustrates how combining traditional fieldwork with modern analytical tools can transform stray flint chips and faded hearths into rich tapestries of human history. As more results emerge from the ongoing analyses of the Baruun Khuree artifacts—particularly the ceramic and ostrich eggshell pieces—a clearer picture will emerge not just of this single valley, but of a broader cultural and environmental story.

The Gobi Desert is not, and never was, a void. It was a corridor—a mosaic of lakes, grasslands, and mountains that beckoned to ancient peoples, offering refuge, opportunity, and perhaps even a sense of belonging. Its early Holocene inhabitants were neither primitive nor peripheral. They were innovators, artists, and survivors at a pivotal moment in human history when the world was warming, ecosystems were shifting, and humanity was learning how to live in new ways.

As the wind still scours the rocks of Flint Valley, it whispers secrets of the past to those who listen closely. And thanks to new research, the valley is finally speaking more clearly—one radiocarbon date, one flake of flint, one shard of pottery at a time.

More information: P. Bobrowski et al, The earliest Holocene wanderers through the Gobi Desert evidenced by the radiocarbon chronology of the lakeshore settlement near the Tsakhiurtyn Hondi, Mongolia, Radiocarbon (2025) DOI: 10.1017/RDC.2025.4