In the silent immensity of the Milky Way, far beyond the comforting warmth of stars, drift worlds without suns—planets cast adrift, wandering the galactic dark. These are the rogue planets, cosmic orphans exiled from the systems that once birthed them. They do not circle any star, nor do they bask in the glow of any dawn. Instead, they travel endlessly through interstellar space, cold, dark, and alone.

To imagine such a world is to confront both awe and melancholy. A rogue planet, floating in eternal night, seems almost a poetic contradiction—a planet without a home, a world without a sky. Yet these lonely wanderers are not rare. Astronomers now believe that for every star in our galaxy, there may be several rogue planets roaming free, outnumbering the visible worlds bound to suns. The Milky Way may contain billions, perhaps even trillions, of these unseen drifters.

They are ghosts of creation, relics of celestial violence and chaos. Some were born around stars but were flung away by gravitational battles. Others may have formed alone, in isolation, from collapsing clouds of gas too small to ignite into stars. Though they travel in darkness, they are not forgotten—because even without light, they carry within them the secrets of how planets and systems are born.

The Discovery of Worlds Without Suns

The idea of a planet wandering through space without a star once seemed like fantasy. Before the 20th century, planets were defined by their relationship to stars—they were the celestial companions of suns, bound by gravity and illuminated by their light. The notion of a planet unbound from any star defied imagination, for how could such a body exist, and how could it be seen?

That changed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, when astronomers began detecting the first hints of these dark wanderers. Using techniques such as gravitational microlensing—where the gravity of a planet bends and magnifies the light of a distant background star—scientists were able to infer the presence of unseen masses drifting through space.

One of the most groundbreaking discoveries came in 2011, when researchers from the MOA and OGLE collaborations announced evidence for a population of free-floating planets roughly the size of Jupiter. The study suggested that there might be at least as many rogue planets as there are stars in the Milky Way. Since then, advances in infrared astronomy, particularly through instruments like NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, have continued to reveal the shadows of these solitary worlds.

Each discovery challenges our understanding of what a planet truly is. A rogue planet has no orbit to define it, no sunlight to reveal it, and yet it remains a planet in every sense—a body formed from cosmic dust and gas, shaped by gravity, and sculpted by the same forces that gave birth to our own world.

The Making of a Drifter

Rogue planets emerge from the same chaotic dance that forms stars and solar systems. In the swirling disks of gas and dust surrounding newborn stars, countless planetary embryos compete for material. Some grow massive enough to dominate their surroundings, while others are perturbed, scattered, or consumed.

In this cosmic turmoil, a planet can easily be cast out. A close gravitational encounter with a larger planet or passing star can hurl a smaller world beyond the gravitational reach of its parent sun. Once ejected, the planet continues moving in the direction it was flung, bound by nothing but the faint gravitational pull of the galaxy itself.

Other rogue planets may never have known the warmth of a star at all. In dense regions of molecular clouds, small pockets of gas can collapse under their own gravity, forming planet-sized objects directly—essentially failed stars. These are often referred to as “sub-brown dwarfs,” bodies too small to ignite fusion but massive enough to hold themselves together. They form independently, born into solitude rather than exile.

The distinction between these two origins—ejected planets and isolated formations—is more than academic. It reflects two paths to planetary existence: one marked by violence and loss, the other by isolation from the beginning. Either way, the result is the same—a world adrift, fated to wander the galactic dark forever.

Life in Eternal Night

At first glance, a rogue planet seems utterly inhospitable. Without a star, there is no sunlight, no warmth, no seasons. The surface would be frozen, the atmosphere, if any, condensed into ice. Such a world would appear lifeless, its frozen plains stretching beneath a black sky unbroken by dawn.

Yet, as with so many assumptions in science, the truth may be far more complex—and far more fascinating. Beneath their icy shells, rogue planets may harbor warmth born not of sunlight, but of their own internal energy.

Even without stellar heat, a planet’s interior can remain warm for billions of years due to radioactive decay and residual heat from formation. If the planet is massive enough to retain a thick atmosphere of hydrogen, it could trap this internal heat, creating a surface temperature suitable for liquid water. Models suggest that a large, Jupiter-sized rogue planet with a dense atmosphere could maintain oceans beneath perpetual cloud cover—even while drifting through interstellar space.

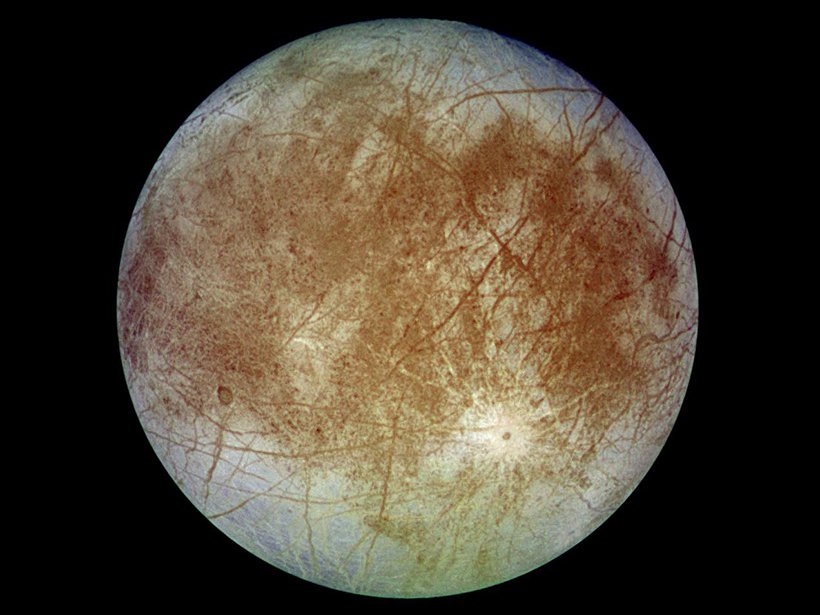

Smaller, Earth-sized rogue planets might also sustain subsurface oceans, much like the icy moons Europa and Enceladus within our own Solar System. Beneath kilometers of ice, geothermal heat could keep liquid water stable, perhaps even nurturing microbial life. In such hidden oceans, life could thrive in total darkness, powered not by sunlight, but by chemical reactions and hydrothermal vents—much like the ecosystems found in Earth’s deep oceans.

This possibility has profound implications for astrobiology. If life can exist on rogue planets, it may mean that life is not limited to the cozy zones around stars. Instead, it might arise anywhere water, chemistry, and energy coincide—even in the endless night between the stars.

The Search for the Invisible

Detecting rogue planets is among the greatest challenges in modern astronomy. Deprived of starlight, they are nearly invisible against the blackness of space. Yet the ingenuity of astronomers continues to uncover their presence through indirect means.

Gravitational microlensing remains the most powerful tool. When a rogue planet passes in front of a distant star, its gravity briefly bends and magnifies the star’s light, creating a distinct signature. By observing these fleeting events, astronomers can estimate the mass and distance of the intervening planet. The larger the planet, the stronger the lensing effect.

Infrared observations also play a crucial role. Young rogue planets, still warm from their formation, emit faint infrared radiation that can be detected by sensitive instruments. Telescopes like the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have identified several isolated objects that blur the line between large planets and small brown dwarfs.

Future missions promise even greater insight. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope will enable more precise microlensing surveys and deeper infrared imaging. With these tools, astronomers hope to map the hidden population of rogue planets across the galaxy and uncover their origins, diversity, and abundance.

The Scale of Solitude

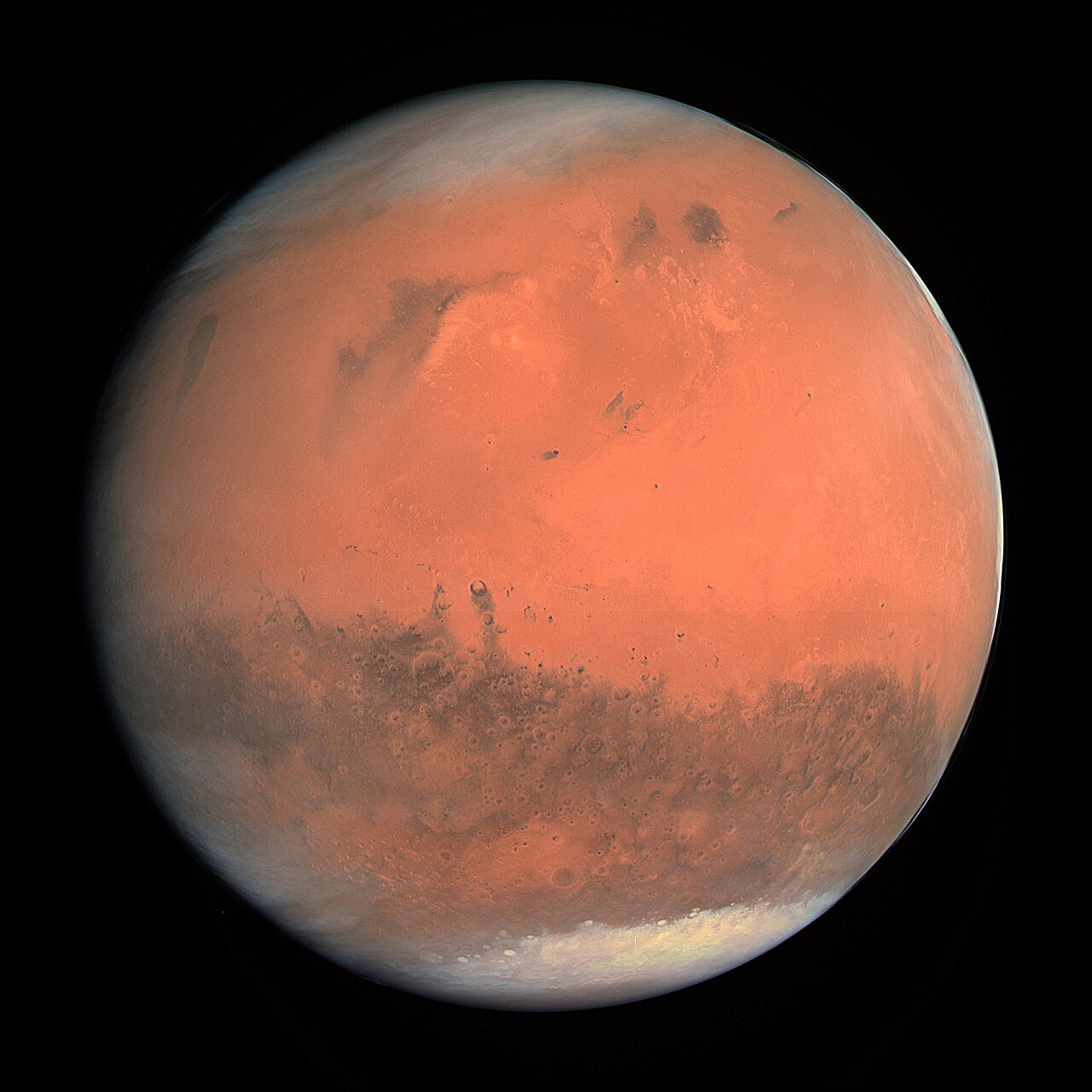

The numbers are staggering. Estimates suggest that there may be hundreds of billions of rogue planets drifting through the Milky Way—perhaps more than the stars themselves. Some may be as small as Mars; others, as massive as Jupiter or even larger. A few may have moons of their own, frozen companions orbiting a frozen master, all adrift together in the void.

This realization transforms our picture of the galaxy. Between the shining constellations we see at night lies a vast unseen archipelago of worlds—cold, silent, and unlit. The space between stars, once thought empty, may in fact be filled with these planetary nomads, each carrying its own history, chemistry, and potential.

Some scientists speculate that rogue planets might occasionally pass close to other stars, briefly illuminated as they traverse foreign systems. A few may even be captured by new suns, finding a second chance at belonging. Others may drift forever, tracing orbits not around stars, but around the galactic center—a slow pilgrimage through eternity.

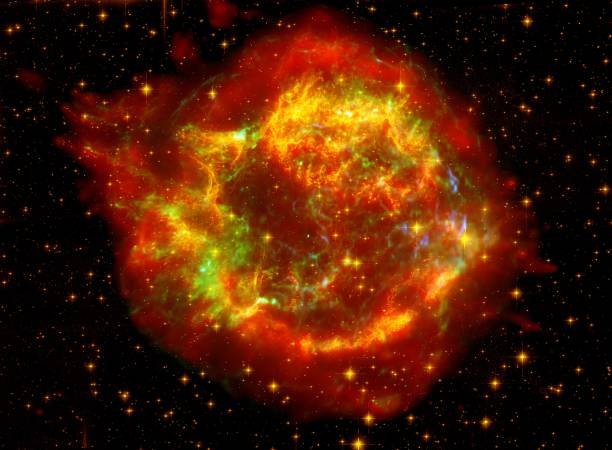

The Echo of Creation

Rogue planets remind us that planetary systems are not static, harmonious structures, but products of dynamic, often violent evolution. Our own Solar System likely ejected many such bodies in its youth. Simulations suggest that during the formation of the giant planets, gravitational interactions would have tossed numerous smaller worlds into interstellar space. Some of these may still wander between the stars, carrying fragments of our Solar System’s early history.

The discovery of rogue planets has also reshaped our understanding of cosmic formation. It suggests that planet-making is a universal process, not confined to the gentle nurturing of starlight. Even the raw materials of planets—gas, dust, and gravity—can assemble into worlds independently. This means that the ingredients for planetary creation are abundant, and the galaxy may be teeming not only with stars and systems, but with solitary worlds as well.

In this sense, rogue planets are fossils of cosmic evolution—remnants of ancient systems, their trajectories written in the invisible architecture of the Milky Way.

The Physics of Darkness

To exist without a sun is to face the harsh physics of interstellar space. Rogue planets must endure extreme cold, cosmic radiation, and isolation. The temperatures of their surfaces can drop to near absolute zero—around -270°C. Any atmosphere not bound tightly by gravity would freeze or evaporate into space, leaving a barren landscape of rock and ice.

Yet physical models reveal that some rogue planets might retain surprisingly dynamic interiors. The decay of radioactive elements such as uranium and thorium can generate geothermal heat. In massive planets, this heat, combined with thick hydrogen envelopes, can sustain internal pressures and temperatures sufficient to prevent complete freezing.

Moreover, a planet with a molten iron core could still produce a magnetic field, shielding its interior from cosmic radiation. This magnetic cocoon could preserve subsurface conditions favorable to chemistry and perhaps to life. The absence of sunlight does not mean the absence of activity. Even in the deep cosmic night, physics provides a faint pulse of energy—a spark of endurance against oblivion.

Rogue Planets and the Seeds of Life

One of the most fascinating ideas in modern astrobiology is that rogue planets may play a role in spreading life across the galaxy. The concept, known as panspermia, suggests that microorganisms could travel between worlds, carried by meteorites, comets, or planetary debris.

If a planet bearing life were ejected from its system, it might carry with it the building blocks of biology—frozen within ice or protected underground. As it drifts through interstellar space, collisions with other bodies or encounters with star systems could scatter this material further, potentially seeding new worlds.

This cosmic migration of life, though speculative, paints a powerful picture of interconnectedness. Life, once begun, may not be confined to a single world or star. The galaxy itself could be a living network, with rogue planets serving as silent couriers of biology—frozen arks adrift in an ocean of stars.

When a Rogue Passes Close

What would happen if a rogue planet passed through our Solar System? Astronomers have considered this possibility, though the odds are small. A massive rogue entering the outer Solar System could perturb the orbits of comets and asteroids, potentially sending some toward the inner planets. In extreme cases, a close encounter could destabilize orbits or even capture the rogue into a distant, eccentric trajectory.

Such events are rare on human timescales but common in cosmic history. The Milky Way’s crowded spiral arms occasionally bring stars—and their attendant planets—close enough to interact gravitationally. Over billions of years, countless planets have been traded, ejected, or captured, reshaping the architecture of entire systems.

If a rogue planet were ever captured by the Sun, it would become a new world within our family—a ghost from another system finding refuge in ours. The idea of such a visitor stirs both scientific and poetic fascination: a foreign world, ancient and alone, suddenly illuminated after eons in the dark.

The Instruments of Revelation

Our ability to find rogue planets continues to evolve with technology. Instruments that detect the faintest distortions in starlight or the weakest whispers of infrared radiation are opening windows into the invisible universe.

Gravitational microlensing surveys such as OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) and MOA (Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics) have already revealed populations of Jupiter-mass rogues. The European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, which maps the positions of over a billion stars, may soon detect subtle motions indicating unseen planetary masses drifting nearby.

The upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to launch later this decade, will revolutionize this search. With its high-resolution wide-field imaging, it could detect Earth-sized rogue planets across the galaxy. For the first time, we may begin to measure not just their abundance, but their diversity—their sizes, compositions, and ages.

Meanwhile, infrared observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope will help us study the atmospheres of nearby free-floating worlds. Some young rogue planets still glow faintly from residual heat, allowing scientists to analyze their chemistry and temperature profiles. Through such observations, we may even glimpse weather systems—storms and winds—on planets that have never seen the light of a star.

The Philosophy of Solitude

Beyond science, rogue planets evoke deep philosophical reflection. They remind us of isolation, of exile, of the spaces between. A rogue planet is a symbol of endurance in solitude—a world that continues to exist even when severed from the warmth that gave it birth.

Yet their solitude is not emptiness; it is persistence. These planets drift for billions of years, untouched, carrying within them the memory of creation. They are monuments to the resilience of matter and motion—a cosmic testament that even in darkness, existence continues.

In a way, rogue planets mirror the human condition. We, too, are travelers through vast darkness, seeking meaning in an indifferent cosmos. Our Sun will one day fade, our world will change, yet life and consciousness may continue to wander, just as these planets do. The rogue planet is not merely a scientific object; it is a metaphor for survival, for the enduring journey of being.

A Hidden Universe Revealed

As our instruments grow more sensitive and our theories more refined, we are beginning to perceive the true shape of our galaxy—a realm not of empty space but of hidden worlds. Rogue planets fill the darkness between stars, transforming the cosmic void into a rich tapestry of unseen motion.

Somewhere out there, in the unlit corridors of the Milky Way, countless worlds drift silently. Some are frozen giants, others rocky spheres sheathed in ice. Some may still glow faintly from their birth. A few may even shelter warmth beneath their crusts, with seas where strange biochemistries stir in the dark.

The discovery of rogue planets expands the boundaries of what it means to be a “world.” It reminds us that a planet is not defined by its parent star, but by its own nature—its gravity, its chemistry, its potential to harbor life. Just as the universe creates diversity among the stars, it grants independence to its planets, scattering them like seeds across interstellar space.

The Legacy of the Wanderers

The story of rogue planets is still being written. We are only beginning to count them, to glimpse their shadows against the light of distant suns. Each detection adds another verse to the cosmic narrative—a story of formation, ejection, and endurance.

They are the wanderers, the exiles, the eternal travelers of the galaxy. They remind us that the universe is not orderly but dynamic, not predictable but alive with motion and transformation. Systems are born, worlds collide, and even planets can be cast into endless night—yet nothing is ever truly lost. Each rogue carries a fragment of its origin, a spark of the processes that shaped stars, systems, and life itself.

Perhaps one day, as our technology and curiosity advance, we will send probes to explore one of these dark worlds. Imagine a spacecraft, traveling for centuries through interstellar space, finally approaching a rogue planet. Its sensors detect warmth beneath an icy crust, perhaps even liquid oceans below. In that moment, we would realize that even in the void, the universe has not forsaken life—it has simply hidden it in unexpected places.

The Eternal Drift

The Milky Way spins silently, its stars orbiting the galactic center like bright islands in a cosmic sea. Between them, unseen, float the rogue planets—worlds without dawn, carrying the weight of time and solitude. They do not burn, but they endure. They do not shine, but they persist.

In their endless drift, they remind us that belonging is not defined by proximity to light, but by the gravity that holds us together. Even alone, they remain part of the greater structure, bound by the unseen pull of the galaxy’s heart.

One day, perhaps, we will follow them into the dark—not to escape the Sun, but to understand the fullness of the universe. And when we do, we may find that the void between stars is not empty at all, but filled with worlds still waiting to be known.

The rogue planets, drifting endlessly through the galaxy, are not lost. They are the quiet witnesses of creation, the keepers of cosmic memory. They are the proof that even in darkness, there are worlds—and where there are worlds, there may always be wonder.