Deep in the historical mist that envelops the ancient Mediterranean world lies a forgotten people—a civilization that once flourished on the edge of the known world, then vanished so thoroughly that even their name sounds mythical. The Tartessians were among the first advanced cultures of Western Europe, emerging in the fertile lands of southern Iberia where the Atlantic meets the Mediterranean. They traded with Phoenicians, mined vast riches of silver and gold, and left behind cryptic ruins and tantalizing clues.

Were they a kingdom of seafarers who challenged the Phoenicians? A cradle of lost wisdom that once inspired Greek legends? Or merely a footnote in the grand narrative of history?

The story of Tartessos is part archaeology, part mythology, and part detective mystery. As we unravel the secrets of the Tartessians, we travel across sunbaked plains, into burial mounds, and through the ancient trade routes of the Mediterranean. Join us as we piece together a civilization that once shimmered like gold on the horizon of antiquity—and then disappeared without a trace.

The First Glimmers: Where Was Tartessos?

The name “Tartessos” first appears in the writings of Greek historians like Herodotus, who described it as a prosperous kingdom located beyond the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar). It was said to be a land rich in metals, particularly silver and gold, and home to a powerful king named Arganthonios who ruled for 80 years. Herodotus even claimed that Tartessians had diplomatic contact with Greeks as early as the 7th century BCE.

But these classical texts were vague. They spoke of a land at the edge of the world—mysterious, wealthy, and remote. Archaeologists eventually turned their attention to the region around the Guadalquivir River in southwestern Spain. Here, in the modern provinces of Huelva, Cádiz, and Seville, a trove of archaeological findings has painted a fascinating, if fragmented, picture.

This area was indeed a center of metalworking and trade from at least the 9th century BCE. The Tartessians likely occupied this region—where the Atlantic tide rolls inland—and built cities that buzzed with life, industry, and innovation. Yet no capital city has ever been found. Tartessos may have been a network of urban centers, connected by trade and culture, rather than a single metropolis.

A Land of Silver and Song: The Economy of Tartessos

The lifeblood of Tartessos was metal. The Iberian Peninsula has long been rich in natural resources—particularly in the Río Tinto area, which held massive reserves of silver, copper, and gold. The Tartessians mined these metals with remarkable skill and traded them with far-off cultures. Their silver may have ended up in Phoenician temples or Greek coinage.

Tartessians were not only miners but also skilled artisans. Gold jewelry, intricate silverwork, and ceremonial items—many found in burial sites—testify to their craftsmanship. Objects such as the “Treasure of El Carambolo,” a collection of gold artifacts discovered near Seville in 1958, speak to a society that combined wealth with ritual significance.

But Tartessos was more than just a mining economy. They raised livestock, cultivated olives and grapes, and developed a vibrant agricultural base. Their strategic location allowed them to act as intermediaries between the Atlantic and Mediterranean trade networks. They exported tin and silver and imported luxury items like glass, ivory, and ceramics.

This economic dynamism fueled urbanization. Tartessian settlements, such as those excavated at Huelva and Casas del Turuñuelo, reveal structured cities with temples, large buildings, and clear evidence of social hierarchy.

Voices in Stone: Language and Writing

One of the most tantalizing mysteries of Tartessos is its language. Archaeologists have discovered inscriptions in what is now called the “Tartessian script”—a semi-syllabic writing system etched onto stone and ceramics. It bears some resemblance to the scripts used by the Iberians and possibly even the Phoenicians.

However, the Tartessian language remains undeciphered. We can read the script phonetically, but we don’t know what it means. The inscriptions offer names and fragments, but not full stories or records. Unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs or Sumerian cuneiform, there is no Rosetta Stone for Tartessos—no bilingual text to crack the code.

This linguistic enigma deepens the mystery. Who were the Tartessians? What myths, poems, and prayers did they record? Some scholars suggest they spoke a pre-Indo-European language, related neither to Basque nor Celtic tongues. Others believe they may have adopted aspects of Phoenician or Greek vocabulary. Until we can fully translate their inscriptions, the Tartessian voice remains hauntingly silent.

Gods of Sea and Stone: Religion and Belief

Although we know little of Tartessian theology, archaeological evidence reveals a rich spiritual world. Shrines, offerings, and burial customs suggest a belief in life after death and reverence for divine forces. Animal sacrifices were practiced, and gold artifacts often had ceremonial purposes.

The influence of Phoenician religion is unmistakable. As early as 800 BCE, Phoenician traders were active along the Iberian coast, and they brought with them gods like Melqart and Astarte. Tartessian temples sometimes resemble Phoenician architecture, and some artifacts bear Semitic inscriptions or symbols. Yet the Tartessians likely maintained their own pantheon—blending indigenous beliefs with foreign ones in a unique syncretism.

One of the most mysterious finds is the idol discovered at Cancho Roano, a religious complex with altars, murals, and evidence of ritual destruction. The site may have been a temple or a palace, destroyed by fire in a dramatic act of closure. Why was it burned? Was it a sacrificial act, a political upheaval, or an apocalyptic event?

Religion in Tartessos, like much else about this civilization, invites more questions than answers. Their gods have no names, and their myths are lost—but the remnants they left behind hint at a culture deeply rooted in ritual and symbolism.

The Golden King: Arganthonios and the Greek Connection

Among the few Tartessians named in historical sources, one stands out: King Arganthonios. Herodotus claims he ruled for 80 years—perhaps a poetic exaggeration, or a reference to dynastic continuity. He is described as welcoming to Greek visitors, especially the Phocaeans, whom he offered gold to build walls around their city of Phocaea (in modern Turkey).

Arganthonios may symbolize a period of intense Greek-Tartessian interaction. Greek pottery, jewelry, and weaponry have been found in Tartessian sites, suggesting strong ties. Greek stories of distant, wealthy kingdoms—like Atlantis, Hesperides, and the land of the Gorgons—may have drawn inspiration from the western frontier of Tartessos.

Was Arganthonios a historical king or a legendary amalgam? We may never know. But his name—meaning “the Silver One”—seems to embody the wealth and allure of Tartessos in the eyes of the ancient world.

Vanishing Act: The Sudden Disappearance of Tartessos

One of the greatest enigmas surrounding the Tartessians is their disappearance. Around 500 BCE, references to Tartessos vanish from the historical record. Archaeological evidence suggests that many Tartessian cities were abandoned or destroyed during this period.

Why did this happen? Theories abound. Some suggest natural disasters—earthquakes or floods from the shifting Guadalquivir River delta. Others propose political turmoil, possibly caused by the Carthaginians (Phoenician descendants) who rose to power in Iberia and may have crushed their Tartessian competitors. Still others suspect that Tartessos simply transformed, evolving into later Iberian cultures that lacked the same centralized identity.

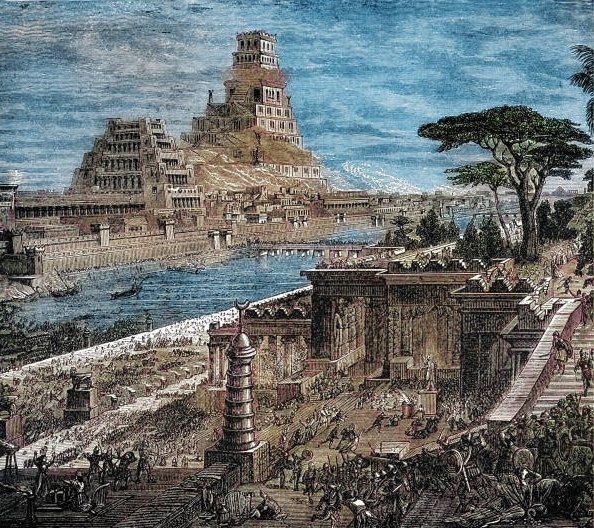

There is also the seductive theory that Tartessos was Atlantis, the fabled island described by Plato. While most scholars reject this idea, the parallels are tempting: a rich maritime culture destroyed suddenly, existing “beyond the Pillars of Hercules.”

Whatever the cause, the silence that followed Tartessos is haunting. A culture that once sparkled with gold and silver, that traded across the seas and built monumental structures, simply… disappeared. No written accounts, no epic tombs, no lingering dynasties. Just fragments.

Echoes in the Soil: Archaeological Rediscoveries

In recent decades, archaeology has begun to fill in the void. Excavations at sites like El Carambolo, Cancho Roano, and Casas del Turuñuelo have uncovered temples, tombs, and urban layouts. New radiocarbon dating and metallurgical analysis have linked these sites to the peak of Tartessian civilization between 850 and 550 BCE.

Casas del Turuñuelo, in particular, has offered unprecedented insight. Discovered in the 1990s and excavated more thoroughly in the 2010s, it includes a monumental building with staircases, painted walls, and a large animal sacrifice site with horses and cattle. It is one of the most elaborate pre-Roman constructions in Iberia.

These finds suggest that Tartessos was far from a primitive society. It was urbanized, hierarchical, ritualistic, and deeply embedded in the Mediterranean world. Yet despite these advances, Tartessos remains archaeologically elusive—no inscriptions explaining its fall, no capital city conclusively identified.

Tartessos in Myth and Memory

The memory of Tartessos lingers not just in artifacts but in stories. Ancient Greeks associated it with the mythical Garden of the Hesperides—a paradise where golden apples grew. Some equated it with Erytheia, the island of the giant Geryon. Others speculated it was a gateway to the afterlife, located at the western edge of the earth.

These myths, passed down through poets and philosophers, may preserve distorted memories of Tartessian glory. The image of a golden kingdom in the far west, lost to time, has universal appeal. It echoes in Arthurian Avalon, Norse Vinland, and of course, Plato’s Atlantis.

Modern writers and thinkers have drawn on Tartessos as well. In Spain, it holds a unique place in cultural imagination—a symbol of pre-Roman sophistication, Iberian pride, and historical mystery. Some fringe theories even claim it was visited by Egyptians or was part of a global ancient civilization. While these ideas lack solid evidence, they underscore the enduring allure of Tartessos.

Conclusion: The Enigma Endures

The Tartessians left no epic tales or written history. What survives are scattered clues—golden artifacts, shattered temples, and cryptic inscriptions—waiting to be deciphered. Their story is one of paradox: a civilization advanced enough to rival its Mediterranean neighbors, yet elusive enough to vanish almost entirely from memory.

What makes the Tartessians so compelling is not just what we know, but what we don’t. They stand as a mirror, reflecting the limits of our knowledge and the mysteries of our past. In a world driven by conquest and record-keeping, Tartessos remains a whisper—a glimmer of ancient brilliance caught in the dust of time.

Their secrets still lie beneath the fields of Andalusia, waiting for new generations of explorers, dreamers, and scientists to bring them back to light.