Hidden among the rugged canyons and sun-scorched sands of southern Jordan lies one of the most mesmerizing remnants of the ancient world—a city carved into rose-colored cliffs, known today as Petra. Revered for its architectural grandeur and wrapped in layers of mystery, Petra is not just a ruin—it is a riddle, a ghost of a civilization that once flourished against all odds in the desert.

Often called the “Rose City” for the color of the stone from which it was carved, Petra is more than a dazzling facade. Beneath its ornate tombs and majestic temples lies a tale of ingenuity, wealth, politics, trade, religion, and survival. It is a city that was lost for centuries—abandoned, forgotten by the Western world, and shrouded in myth—until its rediscovery in the 19th century brought its legacy back to life.

But who built Petra? Why did it disappear? And what secrets does it still keep, buried beneath layers of rock and time? To understand Petra is to journey not just into the past, but into the heart of a lost civilization whose brilliance still echoes through the stones they left behind.

The Nabataeans: Architects of the Impossible

Petra was not the creation of an empire like Rome or Egypt. It was the masterwork of a lesser-known people called the Nabataeans. These Arab traders appeared in historical records around the 4th century BCE, though their roots likely extend further into prehistory. They were nomads who learned to tame the desert, using it not as an obstacle but as a defense.

At a time when vast empires relied on rivers and fertile valleys, the Nabataeans turned the barren terrain of Jordan into a thriving trade nexus. They built Petra in a narrow valley surrounded by towering cliffs, accessible only through narrow passageways like the Siq—a dramatic gorge that snakes through the rock and emerges before the iconic Treasury.

The Nabataeans’ true genius lay in their understanding of water. In a place where rainfall was rare, they developed sophisticated systems of dams, aqueducts, and cisterns to collect and store water. This enabled them to build a city where others saw only wilderness. Petra bloomed with life—lush gardens, public baths, and bustling marketplaces—fed by water systems so advanced they still function in parts today.

Petra’s Place in the Ancient World

By the 1st century BCE, Petra was a cosmopolitan city and the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom. It was a hub of commerce connecting Arabia, Egypt, the Levant, and the Mediterranean. Incense, spices, silk, gold, ivory, and textiles flowed through Petra, making the Nabataeans incredibly wealthy.

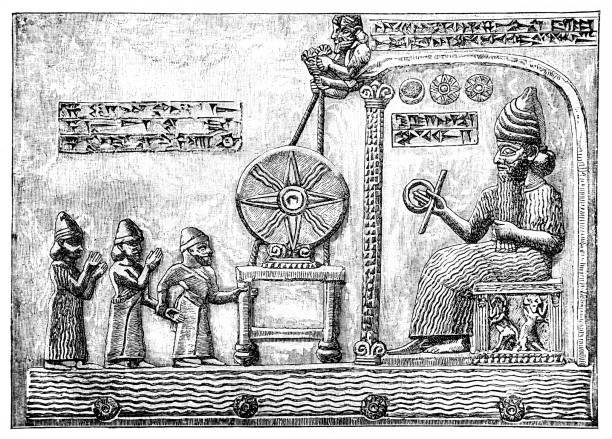

This prosperity is reflected in Petra’s architecture. While the Nabataeans had their own traditions, they eagerly adopted and adapted styles from the Hellenistic and Roman worlds. Their facades feature Greek columns, Egyptian obelisks, and Assyrian carvings—all harmonized into a style that is uniquely Petraean.

The most iconic of Petra’s structures is Al-Khazneh, or “The Treasury.” Rising nearly 40 meters high, this majestic tomb—though originally misnamed by local Bedouins who believed it held treasures—shows a stunning synthesis of Greek artistry and Nabataean symbolism. But it is only one of hundreds of tombs, temples, theaters, and houses carved into the rock.

Petra was more than a religious or funerary site—it was a living city. At its peak, it may have housed as many as 30,000 people, supported by agriculture, trade, and industry. It even had an amphitheater that could seat 8,500 spectators—larger than the population of many Roman towns.

The Fall of Petra

Great cities rise, and great cities fall. Petra’s decline was gradual but inevitable. In 106 CE, the Roman Empire annexed the Nabataean Kingdom, and while Petra continued to thrive for some time, the dynamics of trade began to shift. New maritime routes bypassed Petra, diminishing its strategic importance.

Nature dealt a cruel blow as well. A series of powerful earthquakes in the 4th and 6th centuries CE damaged much of the city’s infrastructure, particularly its water systems. Without water, Petra could not survive. By the time of the early Islamic period, the city was largely abandoned, known only to nomads and local tribes who protected its secrets.

For the Western world, Petra faded into legend. The exact location of the city was lost, whispered in traveler’s tales and ancient writings, until its rediscovery centuries later.

Rediscovery and Western Awe

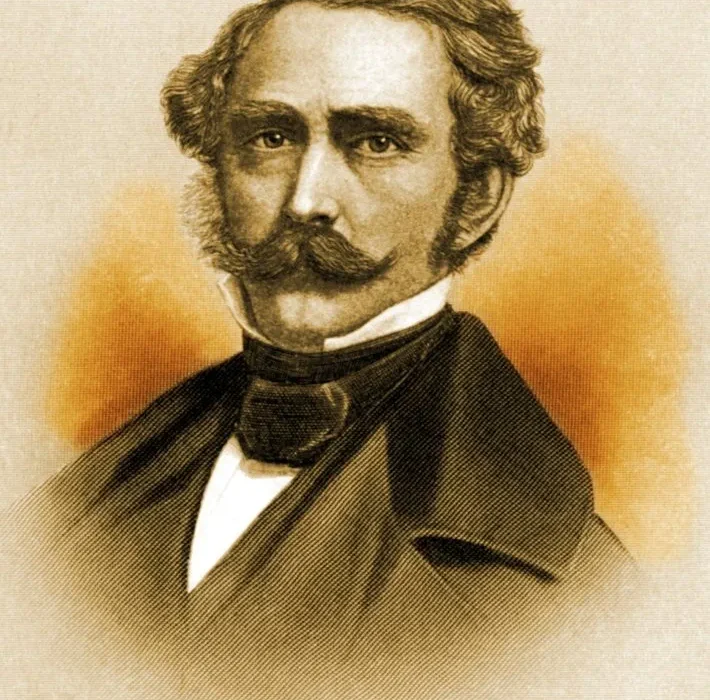

In 1812, a young Swiss explorer named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt ventured into the deserts of Jordan, disguised as a Muslim scholar. He had heard rumors of a hidden city in the cliffs and convinced a guide to take him to a sacred site. Burckhardt became the first European to lay eyes on Petra in centuries, describing its grandeur with awe and astonishment.

His writings electrified Europe. Artists and archaeologists followed in his footsteps, inspired by romantic visions of a lost city. Petra captured the imagination of the West, becoming the epitome of exotic antiquity and mysterious beauty. In the centuries since, Petra has been excavated, studied, photographed, and inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

And yet, even with modern exploration, much of Petra remains buried or unexplored. It is estimated that only 15–20% of the city has been uncovered. The rest lies beneath layers of sand and stone, waiting for future discoveries.

The Language of Stone: Tombs and Temples

Petra’s most remarkable feature is its rock-cut architecture—structures chiseled directly into sandstone cliffs. Unlike other ancient cities that built up with bricks and stone blocks, the Nabataeans carved their city into the very fabric of the landscape.

The facades are stunning in their detail. Some, like the Monastery (Ad Deir), are massive and imposing, with steps leading up to a mountaintop perch. Others are delicate and ornamental, with friezes and columns that echo Greco-Roman styles. Many are tombs, for the Nabataeans practiced elaborate burial rituals. But some served religious, administrative, or social purposes.

Deep inside these monuments, there are chambers that once held bodies, altars, offerings, or gatherings. The interiors are often simple, in stark contrast to the intricate exteriors. But this contrast may be symbolic—emphasizing the grandeur of death or the transition to the afterlife.

Temples like Qasr al-Bint and the Great Temple speak to Petra’s spiritual significance. Worship here was likely complex, involving local deities like Dushara and al-Uzza, alongside imported gods from the Hellenistic world. The blend of religious traditions in Petra suggests a tolerant and cosmopolitan culture.

Engineering Marvels in the Desert

To appreciate Petra is to admire not just its beauty, but its engineering brilliance. The Nabataeans were master builders who adapted to the desert in astonishing ways.

Their water system was a triumph. Channels carved into rock, ceramic pipes, and underground cisterns channeled and stored rainwater from the surrounding mountains. Dams and flood barriers controlled the seasonal torrents that rushed through the Siq, protecting the city and replenishing its reservoirs.

Their roads were equally impressive. Petra was linked to a vast trade network, and the Nabataeans built and maintained caravan routes that stretched across Arabia. They offered security, rest stops, and provisions to traveling merchants—turning Petra into a desert oasis of commerce.

Even their construction methods were advanced. They used scaffolding, levers, and chisels to carve monuments with precision. They understood the rock’s strengths and weaknesses, aligning their facades with natural lines in the stone to prevent collapse. Centuries later, their work still stands as a testament to ancient engineering.

Secrets Still Buried

Despite over two centuries of exploration, Petra still guards its secrets. Many of its chambers and tombs remain unexcavated. Ground-penetrating radar has revealed entire neighborhoods and markets buried under the sand. What lies beneath could reshape our understanding of Nabataean society.

Even Petra’s origins are unclear. Some scholars believe it was inhabited long before the Nabataeans arrived, possibly by Edomites or other ancient tribes. Others suspect hidden crypts, treasure chambers, or sacred texts lie within Petra’s deeper reaches.

New technologies—like drone mapping, 3D modeling, and lidar scanning—are helping archaeologists uncover the city’s past without disturbing its fragile environment. But each answer raises new questions. What was life like for ordinary Petraeans? How did they govern themselves? What were their beliefs, their stories, their dreams?

Petra is a puzzle still missing many of its pieces.

Petra in Modern Times

Today, Petra is Jordan’s crown jewel and one of the most visited archaeological sites in the world. Over a million tourists make the pilgrimage each year, drawn by its majesty and mystery. Its image has appeared in films, books, video games, and popular culture—perhaps most famously in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.”

But this fame comes at a cost. Tourism, weathering, and time threaten Petra’s fragile structures. The sandstone erodes under wind and water, and the constant flow of visitors accelerates decay. Conservation efforts are underway, led by UNESCO and Jordanian authorities, to protect Petra for future generations.

The local Bedouin communities—once guardians of the lost city—are now its guides, entrepreneurs, and storytellers. Their traditions and knowledge enrich the Petra experience, offering insights that no textbook can provide.

Petra is not just a relic; it is a living connection between past and present.

A Legacy of Wonder

The secrets of Petra are not only in its tombs and temples but in its enduring power to inspire. It is a place that challenges our understanding of ancient civilizations. How did a desert people create such splendor? How did they thrive where others would perish? And why does this city, lost and found again, still speak so powerfully to us today?

Petra is more than a city. It is a symbol—of human resilience, of artistic vision, of cultural fusion. It is a monument not only to what was but to what is possible. In every carving, in every stone stairway leading into the cliffs, Petra whispers its story to those who listen.

It is the echo of an ancient people who tamed the desert, carved beauty from stone, and built a legacy that even time could not erase.