In the heart of Iran’s Zagros Mountains, beneath layers of earth steeped in forgotten centuries, archaeologists unearthed the story of a young girl whose head bore the unmistakable mark of an ancient cultural tradition—and whose life ended in sudden, violent tragedy. It is a haunting reminder that even in the deep past, beauty, identity, and death were often intimately entwined.

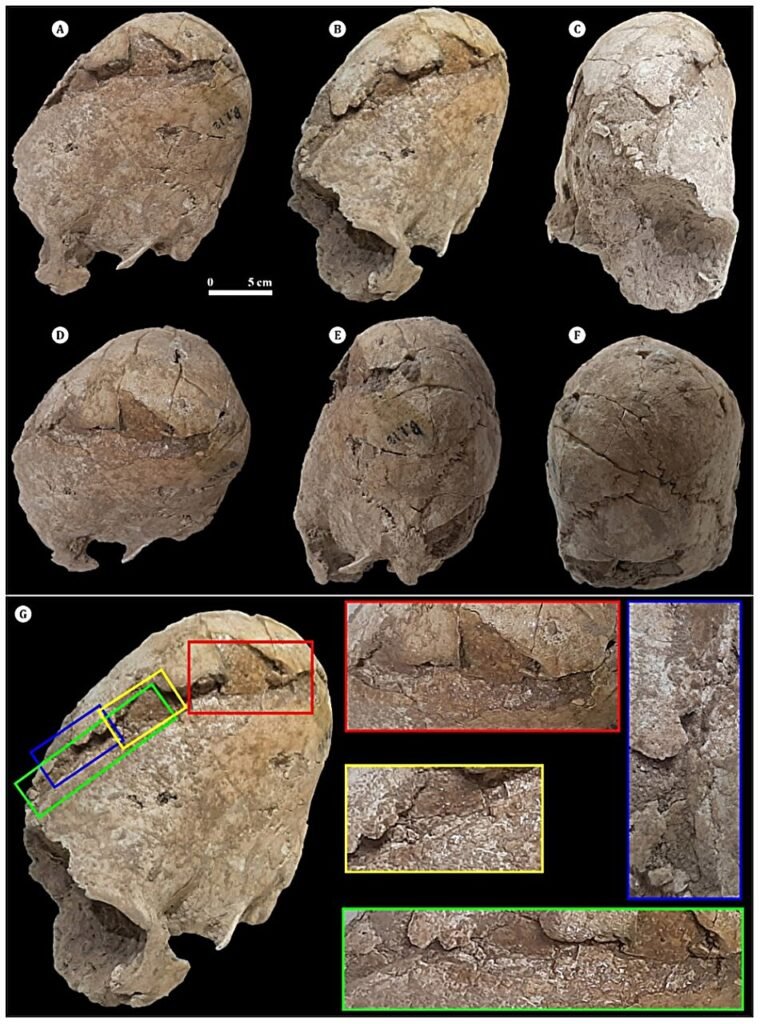

The discovery took place at Chega Sofla, an archaeological site in western Iran that has, for more than a decade, steadily peeled back the secrets of a 6,200-year-old cemetery. Among hundreds of skeletons buried in single and communal graves, one stood out: a solitary skull, fragile and distinctively shaped, emerging from the soil like a voice calling from another era.

The skull belonged to a girl under 20 years old. Her name is lost to time, but her story is now beginning to emerge thanks to researchers Mahdi Alirezazadeh and Hamed Vahdati Nasab. In their newly published paper in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, the pair detail the results of a forensic and cultural investigation that combines modern technology with historical inquiry. Their findings offer a glimpse not only into the customs of a long-lost civilization, but also into the personal suffering of one of its youngest members.

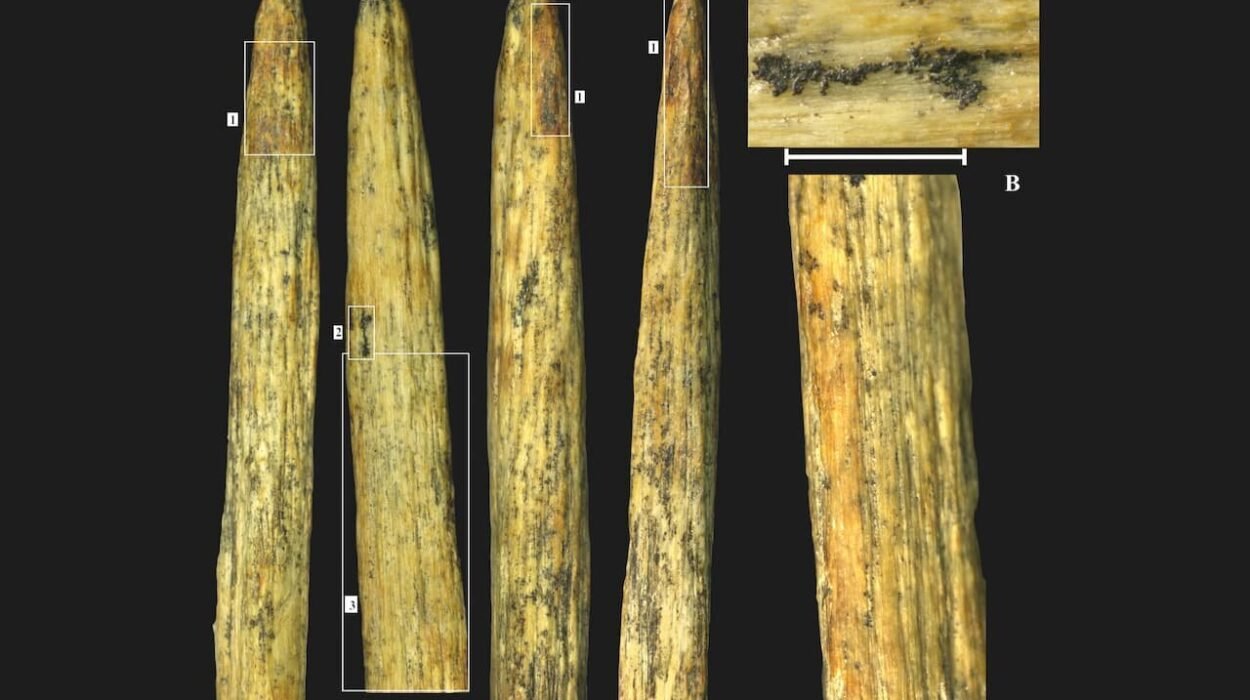

At first glance, the skull appeared unusual: elongated and cone-shaped, almost alien to the modern eye. But this was no accident of nature. The girl had undergone cranial modification, a deliberate and time-consuming process performed in many ancient cultures across the globe. In her case, it involved tightly wrapping her head with bandages or wooden boards during early childhood—when the bones of the skull were still soft and malleable. Over years, her head was reshaped into a tall, tapering form that was likely considered beautiful, noble, or spiritually significant by her people.

This practice wasn’t unique to Iran. From the Andean highlands of South America to the steppes of Central Asia, cranial modification has been found in civilizations separated by oceans and millennia. It was often used to signify social status, group identity, or aesthetic ideals. In many cultures, girls were more frequently subjected to the practice than boys—perhaps a clue to the role appearance played in defining their societal worth.

But while the reshaped skull may have once served as a badge of honor, it also came at a cost. CT scans performed by the researchers revealed that the bone structure of the girl’s skull was unnaturally thin—particularly at the crown. This fragility, they note, would have left her more vulnerable to trauma.

And trauma, tragically, was how she died.

The scans show a devastating fracture stretching from the front to the back of her skull. The break is clean, with no signs of healing—meaning the injury occurred at the moment of death. The force was blunt, broad, and likely deliberate. The researchers propose that a heavy-edged object was used—something wide enough to deliver a shattering blow without penetrating the skull. Given her reduced cranial thickness, the impact reached the brain with fatal consequences. She likely died instantly.

There is no way to know who struck her. Was it an act of war? A personal conflict? A ritual gone wrong? Her body offers no answers. In fact, her full skeleton has yet to be found. The grave where her skull was discovered is packed densely with other human remains, making it nearly impossible to trace the rest of her bones without disassembling the surrounding burials—a painstaking process archaeologists are approaching with caution.

The cemetery at Chega Sofla has already offered up remarkable finds. Among them is the oldest known brick tomb in the region—an architectural marvel that rewrites what we know about early construction in the ancient Near East. But it is this one young girl, anonymous and brutalized, who now captures the imagination of scientists and the public alike.

Her death, though rooted in the distant past, evokes chillingly modern questions: How do cultural ideals shape our physical bodies? At what point does tradition cross into harm? And how do we honor those who suffered silently beneath the weight of societal expectations?

In a world now flooded with debates about body image, gender roles, and historical violence, her story resonates far beyond the arid landscape of western Iran. She reminds us that the past is not just a place of abstract data and stone artifacts—it is a realm of lived experience, of real people whose joys, sorrows, and struggles echo into our own age.

Somewhere beneath the dust of Chega Sofla, the girl’s final resting place remains incomplete. But her legacy has taken root. Through science, patience, and empathy, she speaks again—not in words, but in the silent testimony of her bones.

And in that silence, we are listening.

More information: Mahdi Alirezazadeh et al, A Young Woman From the Fifth Millennium BCE in Chega Sofla Cemetery With a Modified and Hinge Fractured Cranium, Southwestern Iran, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oa.3415