In the heart of Greek mythology, where gods and mortals entwine in tales of glory and ruin, few symbols radiate as much awe and terror as the Aegis. This legendary shield, said to belong to Zeus—the father of gods and men—was no ordinary weapon of defense. It was a manifestation of divine authority, a beacon of cosmic power, and a symbol of the gods’ unchallenged supremacy. To see the Aegis was not merely to face a shield; it was to stand before the raw force of Olympus itself.

The myths whisper of its brilliance, its terrifying visage adorned with the head of Medusa, and its uncanny ability to instill panic in armies and silence in kings. The Aegis was more than an object—it was a concept. It embodied divine protection, overwhelming fear, and the unbreakable authority of Zeus and Athena. Its story weaves together religion, symbolism, and history, offering us a window into how the ancients imagined the ultimate expression of power.

The Origins of the Aegis

The word “aegis” (aigis in Greek) carries with it a mystery. Its roots are debated among scholars. Some trace it to the Greek word aix, meaning “goat,” suggesting a connection to a mythical goat’s skin, perhaps from the divine goat Amalthea who nursed the infant Zeus. Others see its origin in pre-Hellenic or even Near Eastern traditions, where protective hides and shields symbolized divine power.

According to myth, the Aegis was not forged by human hands but was crafted in the heart of divinity. It was sometimes described as the skin of a divine goat, sometimes as a bronze shield, and sometimes as a storm-cloud enveloping Zeus’s will. In Homer’s Iliad, it is a shimmering object of war, blazing like lightning, shaking the very earth when Zeus wielded it. In Hesiod’s works, it is a symbol of storm and wrath.

Its most striking feature was the Gorgon’s head—the face of Medusa, slain by Perseus and placed upon the shield to petrify all who dared to gaze upon it. Thus, the Aegis was not merely defensive; it was a weapon of psychological and supernatural destruction.

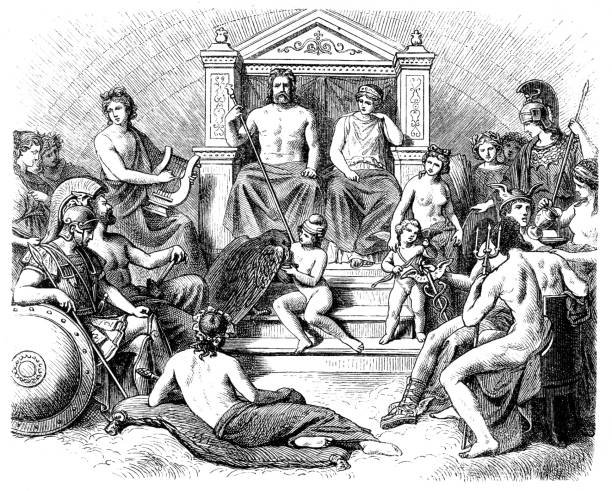

Zeus and the Supreme Authority

Zeus, as the wielder of the thunderbolt, already embodied the cosmic forces of order, law, and justice. Yet the Aegis enhanced his presence. When Zeus shook the Aegis, storms thundered, armies scattered, and the very air seemed to tremble. It was more than a tool—it was a cosmic amplifier of fear and authority.

Homer describes moments in the Trojan War when Zeus unleashes the Aegis. The battlefield shifts instantly—warriors are paralyzed, gods themselves turn their gaze, and mortals cower in awe. It represented the divine right of Zeus to command the heavens, the earth, and the fate of mortals.

In essence, the Aegis was Zeus’s assertion that his reign was supreme. Just as the thunderbolt symbolized his destructive might, the Aegis symbolized his unchallengeable sovereignty. It was the shield that no god or mortal could defy.

Athena and the Borrowed Power

Though the Aegis was first associated with Zeus, it was often wielded by his daughter Athena, goddess of wisdom and war. Unlike her father, Athena’s use of the Aegis reflected not only raw power but also strategy and cunning.

In art, Athena is almost always depicted with the Aegis draped across her shoulders or held as a shield. Its surface bore the Gorgon’s head, sometimes framed by serpents, radiating an aura of dread. For Athena, the Aegis was a symbol of protective might, shielding cities and heroes under her favor. Yet it was also an emblem of intimidation, scattering her enemies before a single glance.

The fact that Zeus entrusted the Aegis to Athena reflects her unique place among the Olympians. She was not only a warrior but also the embodiment of divine intellect and justice. In her hands, the Aegis became not only a weapon but also a symbol of the protective bond between gods and mortals. Cities under Athena’s patronage believed the Aegis shielded them from ruin. In war, generals prayed for its invisible protection.

Thus, the Aegis became as much Athena’s as it was Zeus’s, a shared emblem of authority passed between father and daughter.

The Gorgon’s Face: Terror Encapsulated

No feature of the Aegis was more fearsome than the Gorgon’s head. The Gorgons were monstrous sisters, with snakes for hair, whose very gaze could turn mortals to stone. Medusa, the most famous, was slain by the hero Perseus, who, using a mirrored shield, avoided her gaze and severed her head.

But Medusa’s death did not end her terror. Her head, still retaining its petrifying power, became an object of supernatural dread. Zeus placed it upon the Aegis, ensuring that his enemies not only faced the divine will of Olympus but also the paralyzing fear of the Gorgon’s stare.

The symbolism here is profound. The Gorgon represented chaos, primal fear, and death. By mounting it on the Aegis, Zeus—and by extension, Athena—demonstrated their mastery over chaos, turning terror itself into a weapon. The gods did not simply wield power; they wielded fear.

The Aegis in War and Myth

Throughout Greek mythology, the Aegis appears as a decisive force. In Homer’s Iliad, it is described as “shining, fringed, awful to behold.” When Zeus brandishes it, the skies darken, thunder roars, and armies scatter in panic. It was less a shield than an instrument of divine intervention.

During the Trojan War, Athena used the Aegis to inspire her chosen warriors and terrify their foes. When she revealed the Gorgon’s face, the enemy was stricken with sudden dread, breaking the cohesion of even the strongest forces.

The Aegis was not only a symbol of protection but of psychological warfare. Ancient warfare was not only about swords and spears but also about morale. To face an army under the shadow of the Aegis was to face inevitable defeat, for how could mortals resist a terror drawn from the gods themselves?

The Aegis Beyond the Battlefield

Though often imagined in battle, the Aegis carried meanings that stretched far beyond war. It was invoked in prayers, carved into statues, and carried into ceremonies. For cities devoted to Athena, the Aegis represented divine guardianship. To be “under the Aegis” meant to be under the protection and authority of the gods.

Even in political life, the term endured. Greek city-states invoked the concept of the Aegis to legitimize authority, suggesting their laws and rulers were shielded by divine sanction. The shield thus transcended mythology, becoming part of cultural and political identity.

In art, the Aegis became an icon of divine presence. Sculptures and vases often depicted Athena with the Gorgon-emblazoned Aegis, reminding viewers of her dual role as protector and avenger. It was not just a weapon but a badge of divine legitimacy.

The Aegis and the Natural World

Some scholars interpret the Aegis as not only mythological but also symbolic of natural forces. Zeus was the god of the sky, thunder, and storms. The Aegis, described as a storm-cloud or a roaring wind, may have represented the natural terror of thunderstorms. When Zeus “shook the Aegis,” it was as though lightning split the sky and thunder rolled across the earth.

For ancient peoples, storms were terrifying yet awe-inspiring. They reminded mortals of their fragility and of the vast power of the divine. The Aegis captured this feeling, turning the storm into a weapon of the gods.

Similarly, the Gorgon’s face may have symbolized the destructive power of nature—unpredictable, deadly, and beyond human control. By placing it on the Aegis, Zeus symbolically tamed that chaos, embodying the belief that divine order triumphed over natural disorder.

The Aegis Across Cultures

While the Aegis is uniquely Greek in its mythology, the idea of a divine shield or protective cloak is not limited to Greece. In Near Eastern traditions, gods often carried protective emblems or radiant shields. Egyptian deities bore sacred symbols that repelled evil. Even in Norse mythology, Odin wielded weapons of divine authority, echoing the same archetype.

The Aegis, then, may be part of a broader human impulse to imagine divinity as both protective and terrifying. Across cultures, people turned their fears of nature, death, and chaos into symbols that reassured them of divine order. The Aegis is Greece’s version of this universal archetype—a shield of cosmic authority.

The Aegis in Philosophy and Later Thought

The power of the Aegis extended beyond mythology into philosophy and literature. To be “under the Aegis” became a metaphor for protection, authority, and influence. Even today, the word survives in modern language, used to signify patronage or guardianship.

Philosophers of antiquity often reflected on the deeper meaning of divine symbols. Was the Aegis merely a myth, or was it a metaphor for the natural and psychological power of the gods? Did it represent the authority of law and order over chaos? In these reflections, the Aegis transcended its mythic origins, becoming a tool for thinking about the human condition.

The Aegis in Art and Archaeology

Archaeological evidence shows that depictions of the Aegis were common throughout the ancient Greek world. Vases, reliefs, and sculptures present Athena draped with the Aegis, its serpentine fringe and central Gorgon head unmistakable. It became one of her defining attributes, inseparable from her iconography.

In some cases, fragments of armor or shields discovered in temples may have been offerings dedicated under the symbolic protection of the Aegis. Temples to Athena often included representations of the Gorgon, believed to ward off evil.

These artifacts remind us that for the Greeks, the Aegis was not just a story but a living symbol integrated into daily worship, art, and identity.

The Legacy of the Aegis

Though centuries have passed since the last Greek temple crumbled, the Aegis remains a powerful cultural symbol. It continues to appear in literature, art, and even modern political language. To say that something is done “under the aegis” is to say it is done under protection, sponsorship, or authority.

The shield of Zeus and Athena has thus transcended its mythological roots, finding new life in every era. It is a reminder that symbols, once born, never truly die. They evolve, just as cultures do, carrying fragments of ancient wisdom into new worlds.

The Aegis as Human Imagination

At its core, the Aegis is a product of human imagination. It is how the Greeks gave form to their deepest intuitions about power, fear, and protection. It is how they explained the terror of storms, the awe of divine presence, and the fragile hope of safety in a chaotic world.

The Aegis tells us as much about humanity as it does about the gods. It tells us that humans have always longed for protection against forces beyond their control. It tells us that we have always sought to embody authority in symbols, whether shields, crowns, or flags.

Most of all, it tells us that mythology is not merely about the past—it is about timeless truths, refracted through the imagination of cultures long gone but never forgotten.

The Eternal Shield

The Aegis of Zeus is more than a relic of ancient myth. It is an eternal shield that still casts its shadow across history, language, and imagination. To the Greeks, it was the embodiment of divine terror and protection. To us, it is a symbol of humanity’s need to understand and personify power.

When we read of Zeus shaking the Aegis and the world trembling in response, we are reminded of the awe humans have always felt before forces greater than themselves. When we see Athena cloaked in the Aegis, we glimpse the eternal dream of wisdom married to power, of protection married to justice.

The Aegis is not only the shield of Zeus. It is the shield of human imagination, forever reminding us that to be alive is to live in awe—of nature, of gods, of power, and of the enduring stories we tell to make sense of it all.