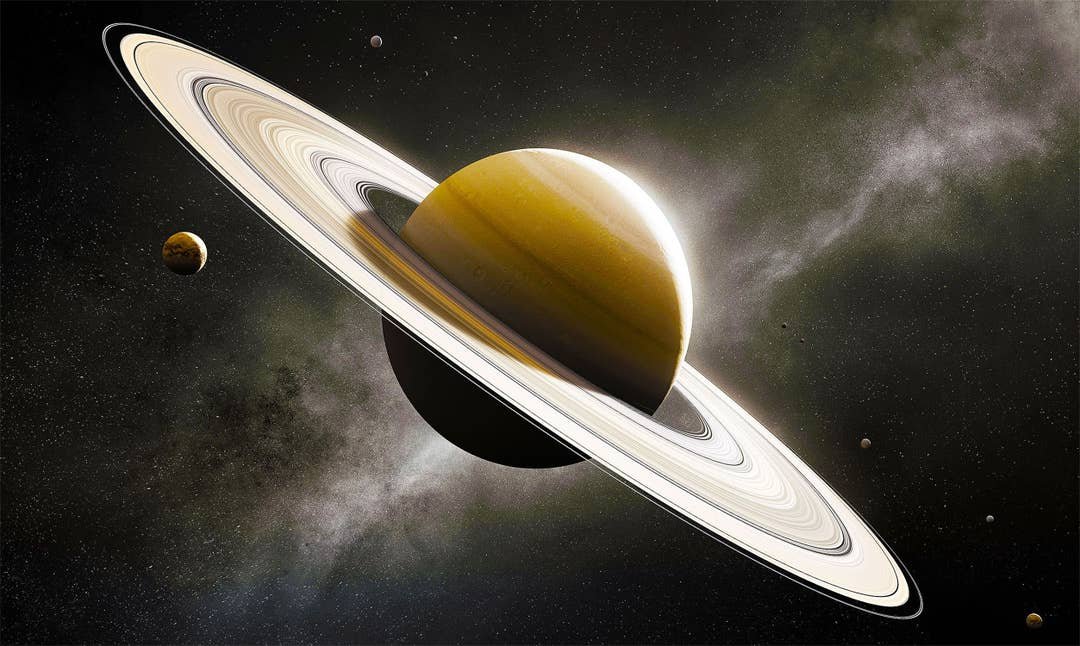

Among the eight planets that orbit our Sun, none is more paradoxical than Venus. Named for the Roman goddess of love and beauty, it shines brighter than any star in the night sky, a beacon of golden light that has inspired awe and fascination since the dawn of human civilization. Yet beneath its radiant appearance lies a world of searing heat, crushing pressure, and relentless storms—a planet that is, in truth, more hellish than heavenly.

But even beyond its infernal surface, Venus defies expectations in a far more perplexing way: it spins backward. Unlike Earth, Mars, or most of the other planets in the Solar System, Venus rotates from east to west. On Venus, the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east, taking nearly 243 Earth days to complete a single rotation. This slow, retrograde spin makes Venus the most enigmatic of all the terrestrial planets, and its strange behavior continues to baffle astronomers and planetary scientists alike.

The mystery of Venus’ backward spin is not just a curiosity—it is a window into the chaotic history of our Solar System. It hints at ancient cataclysms, hidden internal dynamics, and the subtle but powerful influence of gravitational tides. Understanding why Venus turns the wrong way forces us to confront deeper questions about planetary evolution, the nature of motion itself, and the delicate cosmic dance that shapes every world we know.

The Twin That Isn’t

At first glance, Venus and Earth appear to be twins. They are nearly the same size, mass, and density. Both orbit relatively close to the Sun, within what astronomers once called the “habitable zone.” In the early days of astronomy, Venus was imagined as a lush world, perhaps covered in tropical oceans or dense jungles beneath its bright clouds. For centuries, scientists believed it might even harbor life.

That illusion was shattered when the first space probes visited in the 1960s and 1970s. The Soviet Venera missions and NASA’s Mariner spacecraft revealed a world of extremes. Venus’ surface temperature averages 465 degrees Celsius—hot enough to melt lead—and its atmosphere is thick with carbon dioxide, cloaked in clouds of sulfuric acid. The air pressure at the surface is ninety times that of Earth’s, equivalent to being a kilometer beneath the ocean.

And yet, for all these differences, Venus’ similarity to Earth makes its peculiar spin even more intriguing. How could two planets born from the same cosmic disk, forged from similar materials, end up so profoundly different—not only in environment but in the very direction of their rotation? To understand this, we must first look at how planets spin in the first place.

The Origins of Planetary Rotation

The Solar System was born from a vast, rotating cloud of gas and dust some 4.6 billion years ago. As this nebula collapsed under gravity, it spun faster—just as a skater spins faster by pulling in their arms. Within this spinning disk, material clumped together to form the Sun and, eventually, the planets.

Because the entire system rotated in the same direction, the newly formed planets inherited that motion. Most of them, including Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, spin in what astronomers call prograde rotation—they turn in the same direction as their orbit around the Sun, from west to east. This gives the Sun its familiar path across the sky: rising in the east and setting in the west.

In theory, all planets should have kept this inherited spin. Yet reality is far more chaotic. Collisions between young worlds, tidal forces from the Sun, and the redistribution of mass within planets can drastically alter their rotation. Uranus, for instance, is tipped almost on its side, spinning like a rolling ball. Venus, however, took an even stranger path—it turned backward altogether.

The Slowest Day in the Solar System

Venus’ day is longer than its year. It takes 243 Earth days to complete one rotation, while its orbit around the Sun lasts only 225 Earth days. And unlike every other planet except Uranus, Venus spins in the opposite direction.

To grasp how unusual this is, imagine standing on the surface of Venus. The Sun would crawl slowly across the sky, taking 117 Earth days to complete its journey from one horizon to the other. But it would do so in reverse—rising in the west and setting in the east. Between one sunrise and the next, nearly four Earth months would pass, under a sky thick with yellowish haze and a dim twilight caused by the perpetual clouds.

Even stranger, Venus’ spin is nearly perfectly synchronized with its orbit. The same side of the planet tends to face Earth whenever Venus is closest to us, as though the two worlds are locked in a slow cosmic waltz. This resonance hints that Venus’ rotation is shaped not just by ancient impacts, but also by the subtle gravitational pull of our planet and the Sun.

The Cataclysm Hypothesis

One of the earliest explanations for Venus’ backward spin involved a massive collision. In the chaotic early Solar System, collisions between planet-sized bodies were common. Earth itself is thought to have endured such an impact when a Mars-sized object struck it, ejecting material that coalesced into the Moon.

Perhaps Venus experienced something similar—but with a twist. A glancing collision could have dramatically slowed its rotation or even reversed it. A sufficiently large impact might have tilted Venus so far that it effectively flipped upside down, giving the illusion of backward rotation.

However, this explanation faces difficulties. Venus shows little evidence of a massive impact in its current topography. Its surface is relatively young—less than a billion years old—due to extensive volcanic resurfacing. Any ancient scars may have been erased, but even so, simulations suggest that it would take more than one collision to reverse Venus’ spin entirely. The cataclysm hypothesis remains plausible, but not complete. Something else, subtler and more enduring, may have finished the job.

The Power of Tidal Forces

A more refined explanation lies in the quiet but persistent tug of gravity. The Sun exerts tidal forces on every planet, just as the Moon pulls on Earth’s oceans. Over eons, these tidal interactions can alter a planet’s rotation, gradually slowing it down or even reversing its direction.

Venus is particularly vulnerable to this effect because of its proximity to the Sun and its dense atmosphere. The thick clouds and high surface temperatures generate atmospheric tides—variations in pressure and motion caused by solar heating. These atmospheric tides act like invisible brakes, transferring angular momentum between the atmosphere and the planet’s solid body.

In the case of Venus, these tides may have slowed its initial prograde spin until the rotation nearly stopped. Once the planet’s rotation rate dropped below a certain threshold, the combined gravitational and atmospheric effects could have nudged it into retrograde motion. In essence, Venus may not have been born spinning backward—it may have been turned that way gradually by the subtle hand of the Sun.

This theory, known as tidal despinning, is supported by numerical models. They show that a dense, slowly rotating atmosphere can amplify tidal friction, especially if the planet’s rotation period resonates with its orbital motion. Over billions of years, such interactions can lead to the peculiar state we see today—a slow, backward spin locked in near-synchrony with the planet’s orbit.

A World in Balance

Venus’ current rotation is extraordinarily stable. It appears to have reached an equilibrium between opposing forces—the gravitational pull of the Sun and the thermal tides of its atmosphere. The Sun’s gravity tends to slow the rotation, while the thick atmosphere, heated by solar radiation, pushes in the opposite direction.

This balance may explain why Venus’ rotation rate is not perfectly constant but fluctuates slightly over time. Observations from radar mapping missions such as NASA’s Magellan and the European Space Agency’s Venus Express have shown that the planet’s day length varies by a few minutes from decade to decade. These variations are likely caused by interactions between the solid surface, the dense atmosphere, and the tidal forces of the Sun.

Venus thus exists in a delicate dynamic equilibrium—a planet caught in a perpetual struggle between two immense influences. It is a cosmic balancing act, a slow dance that has lasted billions of years and will likely continue for billions more.

The Role of Atmospheric Superrotation

If Venus’ slow, retrograde spin seems strange, its atmosphere is stranger still. High above the surface, hurricane-force winds whip around the planet at speeds exceeding 350 kilometers per hour. This phenomenon, known as superrotation, means that the upper atmosphere circles the planet in just four Earth days—far faster than the planet itself turns.

The mechanism behind this superrotation remains one of the great puzzles in planetary science. It is driven by a combination of solar heating, planetary waves, and the transfer of angular momentum within the atmosphere. In effect, the dense, swirling air of Venus behaves like a separate entity, almost detached from the solid planet below.

Some researchers suggest that the superrotating atmosphere contributes to the planet’s unusual rotation. The exchange of angular momentum between the surface and atmosphere could influence Venus’ overall spin rate, creating a feedback loop that stabilizes its retrograde motion. The atmosphere, in this view, is not just a passive shell—it is an active participant in shaping the planet’s rotational destiny.

The Sun from the Surface of Venus

Imagining the Sun as seen from Venus offers a glimpse into the surreal nature of this world. Because of its slow and backward rotation, a solar day on Venus—the time from one sunrise to the next—lasts about 117 Earth days. The Sun would appear to rise faintly through the thick clouds in the west, drift slowly across a dim orange sky, and set in the east after two Earth months of daylight.

But the Sun’s light would never be direct. The dense atmosphere scatters and absorbs nearly all visible radiation, bathing the surface in an eerie twilight glow. Shadows would be diffuse, colors muted. The heat, however, would be relentless. Beneath the golden clouds, the temperature remains nearly constant day and night, as the thick atmosphere traps heat with astonishing efficiency.

This inversion of the familiar—where day and night blend into an eternal haze, and the Sun moves in reverse—captures the essence of Venus’ enigma. It is a world that reflects our own in form but distorts it in every possible way, a mirror turned backward in space and time.

Venus’ Geological Rebirth

The surface of Venus offers further clues to its mysterious history. Radar mapping by the Magellan spacecraft in the early 1990s revealed a world covered in volcanic plains, mountain ranges, and vast lava flows. Surprisingly, the entire surface appears geologically young—no older than 800 million years.

This suggests that Venus underwent a catastrophic resurfacing event in its past, during which intense volcanic activity erased almost all older features. Such a global transformation could have been triggered by internal heat buildup. Unlike Earth, Venus lacks plate tectonics to release internal energy gradually, so heat may have accumulated beneath the crust until it burst forth in planetwide eruptions.

If this event indeed occurred, it might also have influenced Venus’ rotation. The redistribution of mass across the planet could have altered its moment of inertia, subtly changing its spin rate and direction. Combined with tidal forces, such internal upheavals may have locked Venus into its current retrograde state.

The Clues Hidden in the Atmosphere

Venus’ thick atmosphere does more than smother the planet—it also preserves clues about its evolution. Composed primarily of carbon dioxide with traces of nitrogen and sulfur compounds, it contains isotopic ratios that suggest massive water loss in the distant past. Venus may once have possessed oceans, but they evaporated as a runaway greenhouse effect took hold.

As water vapor rose and dissociated under ultraviolet radiation, hydrogen escaped into space, leaving behind a dry, oxygen-depleted atmosphere. Without oceans to buffer the climate, the surface grew hotter, accelerating the cycle of greenhouse warming. Over time, the planet transformed from potentially habitable to utterly hostile.

This transformation may also have affected Venus’ rotation. Atmospheric escape and volcanic outgassing could have altered the distribution of mass and pressure across the planet, influencing how it interacts with solar tides. Thus, the planet’s climate, atmosphere, and spin are intertwined in a complex feedback system—a reminder that planetary behavior is never dictated by a single cause, but by the interplay of many.

Comparing Venus and Earth

If we could place Venus and Earth side by side, their similarities would be striking. Both are rocky, nearly the same size, and likely formed from similar material. Yet one world is a paradise for life, while the other is a furnace of death. What accounts for this divergence?

Part of the answer lies in their rotation. Earth’s relatively rapid spin creates a magnetic field that shields it from solar radiation, drives its weather systems, and helps maintain a stable climate. Venus, rotating slowly and backward, lacks such protection. Without a significant magnetic field, its atmosphere is bombarded by solar particles, which gradually strip away lighter elements and compounds.

The two planets thus evolved along radically different paths. Earth remained dynamic and life-sustaining; Venus stagnated under a thickening atmosphere and rising heat. Its backward spin may not be the cause of its inhospitable conditions, but it is a symptom of the broader forces that shaped its destiny—a cosmic reminder that small differences in motion can lead to worlds apart in outcome.

Lessons from a Hellish World

Despite its hostility, Venus offers vital lessons for understanding planetary systems, including our own. Its runaway greenhouse effect provides a natural laboratory for studying climate change on a global scale. By examining how Venus’ atmosphere traps heat, scientists gain insight into the delicate balance that keeps Earth habitable—and how easily that balance could be lost.

Venus also demonstrates the profound influence of rotation on planetary behavior. A planet’s spin affects its climate, magnetic field, and even the possibility of life. Understanding why Venus spins backward helps scientists refine models of planetary formation, not just in our Solar System but in the thousands of exoplanets discovered around other stars.

Some of those distant worlds, like Venus, orbit close to their stars and may experience similar tidal forces, leading to slow or retrograde rotations. In that sense, Venus is a key to deciphering the diversity of planetary systems throughout the galaxy.

The Future of Venus Exploration

Though it has long been overshadowed by Mars in popular imagination, Venus is once again becoming a focus of exploration. In the coming decades, multiple missions aim to return to this enigmatic world. NASA’s VERITAS and DAVINCI+ missions will map its surface in unprecedented detail and analyze its atmosphere to uncover clues about its geological and climatic evolution. The European Space Agency’s EnVision mission will complement these efforts with radar imaging and atmospheric studies.

Together, these missions may finally reveal how Venus became the planet we see today—and perhaps, how its spin was shaped by billions of years of cosmic interplay. Some proposals even envision aerial explorers—balloons or airships that could float in the temperate upper atmosphere, where conditions are far more Earth-like. These floating observatories might one day pave the way for human exploration, transforming the “morning star” into the next frontier of discovery.

Venus as a Mirror for Humanity

In the glow of early dawn or twilight, Venus often appears as the brightest object in the sky, outshining every star. To the ancients, it was both the morning star and the evening star—a symbol of renewal, beauty, and constancy. Yet behind that serene light lies a story of transformation and turmoil.

Venus is a warning as well as a wonder. It shows how a planet that might once have been temperate can spiral into catastrophe under the influence of heat, atmosphere, and time. Its backward spin, though a mechanical detail, symbolizes the reversal of fortune—a world that turned against itself.

And yet, there is also poetry in its persistence. Despite its extremes, Venus remains one of the most stable and enduring worlds in the Solar System. Its thick atmosphere, its slow rotation, its timeless glow—they all speak of equilibrium, however harsh. Venus endures, spinning slowly and steadily against the cosmic tide.

The Cosmic Ballet

The Solar System is a dance of giants, each planet moving to its own rhythm yet bound by the same universal laws. Most twirl in unison, but Venus turns the other way—a solitary figure moving gracefully in reverse. Its defiance is not chaos but balance, a reminder that harmony in the cosmos often arises from diversity.

The backward spin of Venus challenges our assumptions about order and symmetry. It tells us that even in a universe governed by predictable laws, chance and complexity still reign. A single collision, a shift in pressure, or a tug from the Sun can change the fate of a world forever.

In the end, Venus’ retrograde rotation is more than an astronomical curiosity—it is a symbol of the unpredictable beauty of the cosmos. It teaches us that every planet carries its own story, shaped by time, chance, and the unseen forces of the universe.

The Eternal Mystery

The enigma of Venus’ backward spin remains one of the most fascinating puzzles in planetary science. We now understand much about how it may have occurred—through collisions, tidal forces, and atmospheric dynamics—but no single explanation tells the whole story. The truth may be a tapestry woven from all these threads, stretching back to the dawn of the Solar System.

As we continue to study Venus, we uncover not only the history of a planet but reflections of our own. Its surface, hidden beneath clouds, guards the memory of cosmic violence and transformation. Its slow rotation reminds us that time flows differently on every world, that the universe holds infinite variations on the theme of motion and light.

Venus, the goddess of love, the morning and evening star, remains a paradox—a world of fire veiled in beauty, turning slowly and silently in the opposite direction of all the rest. And as it shines in our sky, we are reminded that even in a universe of order, there is always room for mystery, wonder, and the unexpected grace of reversal.