Long before humans learned to write or build cities, an ancient world thrived with creatures of colossal size and mysterious nature. Their bones lie buried beneath layers of time, their stories fragmented but evocative—whispers of titanic beings that once roamed Earth. From the towering dinosaurs of the Mesozoic to the shaggy mammoths and fierce saber-toothed cats of the Ice Age, the giants of prehistory are more than just fossils; they are keys to understanding evolution, extinction, and the planet’s ever-changing landscapes.

But not all prehistoric giants are well understood. Some provoke questions still unanswered. Why did so many species evolve to such monstrous sizes? How did they live, move, and interact with their environments? And why did they vanish, leaving behind only bones and mystery?

This is the story of the enigmatic giants of prehistory—a journey through epochs, continents, and scientific revolutions. It’s a story not just of animals, but of our own evolving understanding of life and deep time.

The Dinosaur Colossi: Masters of the Mesozoic

When most people think of prehistoric giants, they picture dinosaurs—and for good reason. Dinosaurs are the undisputed monarchs of prehistory, dominating the Earth for more than 160 million years, from the late Triassic through the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Some of these creatures reached sizes unmatched by any land animals before or since.

Among the most awe-inspiring of these giants was Argentinosaurus, a titanosaur sauropod whose length may have exceeded 100 feet and whose weight was comparable to 10 African elephants. Its neck alone stretched longer than a city bus. Its bones, discovered in Argentina, suggest an animal so large that it may have faced challenges simply supporting its own bulk.

Equally astonishing was Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, perhaps the longest carnivorous dinosaur ever discovered—longer even than Tyrannosaurus rex. Unlike most theropods, Spinosaurus may have been semi-aquatic, using its crocodile-like snout and sail-like back ridge to dominate Cretaceous waterways.

But these giants were not uniformly monstrous. There was incredible diversity: duck-billed hadrosaurs, armored ankylosaurs, horned ceratopsians, and the ever-iconic T. rex—a predator whose bite force is unmatched in the fossil record. The Mesozoic Era was a symphony of giants, each adapted to a niche in a complex, often brutal prehistoric world.

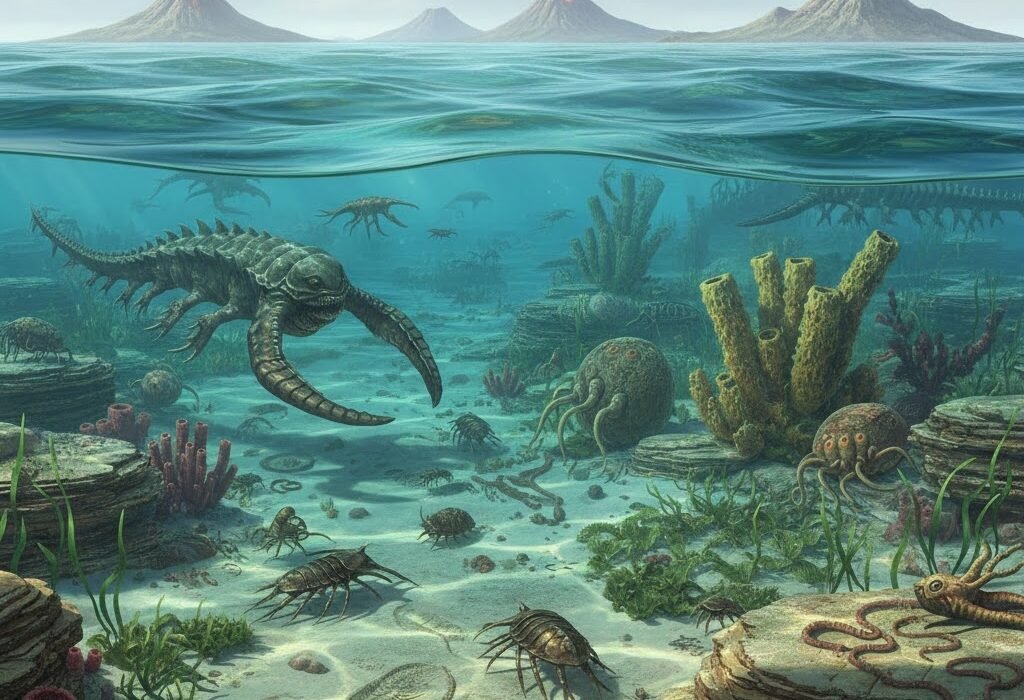

Life Before Dinosaurs: The Forgotten Titans of the Paleozoic

Long before the first dinosaur took its thunderous step, the Earth was already home to giants—some of them eerily alien by today’s standards. The Paleozoic Era (spanning from roughly 541 to 252 million years ago) saw the rise of enormous invertebrates and early vertebrates, living in oceans, forests, and swamps vastly different from modern ecosystems.

In the Carboniferous Period, dense, oxygen-rich atmospheres allowed insects to reach grotesque proportions. Meganeura, a dragonfly-like insect with a wingspan of more than two feet, soared through primordial forests, while Arthropleura, a colossal millipede relative, crawled across the ground measuring up to 8.5 feet in length. These invertebrate giants would be impossible in today’s lower-oxygen world.

Meanwhile, the Devonian Period—often called the “Age of Fishes”—hosted aquatic titans like Dunkleosteus, a prehistoric armored fish that could grow over 30 feet long. Its jawbones, more like blades than teeth, could slice through flesh and bone with tremendous force.

And in the late Permian, before the dawn of dinosaurs, there were therapsids and archosauriforms—early relatives of mammals and reptiles. Among them was Dimetrodon, often mistaken for a dinosaur, which sported a sail-like fin on its back and was one of the dominant predators of its time.

These creatures may not dominate pop culture like dinosaurs, but they were evolutionary trailblazers—pioneers of land conquest and respiratory innovation. Their fossilized remains are rare treasures, telling stories from a world long buried.

The Rise of the Mammalian Giants: Titans of the Cenozoic

The extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs around 66 million years ago paved the way for a new class of giants—mammals. The Cenozoic Era, stretching from the Paleocene to today, saw mammals rise from small, rodent-like survivors to the rulers of vast continents. Freed from dinosaur competition, they evolved into forms both strange and staggering.

One of the earliest post-dinosaur giants was Paraceratherium, a hornless rhinoceros relative and possibly the largest land mammal ever. Towering up to 16 feet at the shoulder and weighing as much as 20 tons, this browsing herbivore roamed the Oligocene plains of Central Asia. Its sheer size challenged the boundaries of mammalian biology.

In South America, isolated for millions of years, evolution went wild. Megatherium, the giant ground sloth, grew as large as modern elephants and lumbered through forests on massive limbs, feeding on foliage. Its cousins, some capable of bipedal rearing, were protected by thick hide and claws as long as scythes.

In the Arctic tundras and grassy steppe of the Ice Age, the most famous of mammalian giants emerged: the woolly mammoth. Covered in thick fur, with long, spiraling tusks and a hump of fat for energy storage, Mammuthus primigenius was a cold-weather marvel. It shared its world with other megafauna like the woolly rhinoceros, cave bears, and saber-toothed cats (Smilodon), whose fanged grins remain iconic.

These mammals were not just physically impressive—they also reflected the climatic upheavals of the Pleistocene epoch. Ice sheets expanded and receded, shaping migration, survival, and, eventually, extinction.

Aquatic Giants: Leviathans of the Deep

While land giants roamed forests and plains, the oceans teemed with their own massive denizens—some of which still exist today. Prehistoric seas hosted creatures so massive and strange that even the largest dinosaurs might seem dwarfed by comparison.

In the late Jurassic, the oceans were patrolled by marine reptiles like Liopleurodon, a pliosaur possibly exceeding 40 feet in length. Its powerful flippers and massive jaws made it a top predator in the aquatic food web.

Later, in the Cretaceous, Mosasaurus—a massive marine lizard and relative of modern snakes—reigned supreme. With a body as long as a city bus and a mouth full of conical teeth, it was immortalized in popular culture after its appearance in “Jurassic World.”

Even after the age of reptiles, the oceans remained home to giants. In the Miocene, Livyatan melvillei, an ancient sperm whale, competed with Megalodon, the largest shark to ever live. This 60-foot behemoth had jaws wide enough to swallow a grown human whole and teeth the size of bananas. Megalodon dominated oceans until it vanished mysteriously around 3.6 million years ago—its extinction a puzzle still debated.

Today’s blue whale, the largest animal ever to exist, is a living descendant of this legacy. At up to 100 feet long and weighing over 180 tons, it dwarfs even the largest dinosaurs, reminding us that nature’s capacity for gigantism did not die with the past.

The Mystery of Gigantism: Why So Big?

What drove so many prehistoric creatures to such incredible sizes? This question has perplexed scientists for centuries. Gigantism is not a random occurrence—it reflects evolutionary pressures and ecological opportunities.

In dinosaurs, gigantism may have evolved due to the advantages of bulk for digestion (especially in herbivorous sauropods), defense, or reproductive success. Their hollow bones and efficient air-sac systems allowed them to grow massive without collapsing under their own weight.

In mammals, large body size often correlates with cold environments (as per Bergmann’s Rule), where a lower surface-area-to-volume ratio helps conserve heat. The Ice Age mammoths are a prime example. Gigantism could also have offered protection from predators and enabled efficient travel across vast landscapes.

In insects of the Carboniferous, gigantism was facilitated by higher atmospheric oxygen levels. These insects rely on passive oxygen diffusion through their exoskeletons, which limits modern insect size. In a world with 35% atmospheric oxygen (compared to today’s 21%), they could grow far larger.

In the oceans, buoyancy neutralizes gravity, allowing massive sizes in marine animals. Gigantism in ocean predators like Megalodon or sperm whales was likely driven by prey abundance and migratory behavior.

Yet gigantism also comes at a cost—massive creatures need more food, have slower reproduction, and are more vulnerable to extinction when environments change. Many of the giants disappeared during periods of climatic upheaval or after human contact.

Giants in Myth and Imagination

Long before science explained fossils, ancient people encountered the bones of giants and sought to understand them through myth. Elephant skulls became cyclopses in Greek lore, while giant bones found in Asia inspired tales of dragons. In Native American cultures, fossilized mammoth remains were sometimes associated with great beasts or ancestral spirits.

The concept of giants is nearly universal in mythology: Norse frost giants, Hindu demons like the Rakshasa, and Biblical figures like the Nephilim. These stories may have roots in real paleontological discoveries—interpreted through the lens of cultural imagination.

Even today, prehistoric giants captivate the public. Museums showcase towering reconstructions, books and films dramatize their lives, and debates continue over their behavior and extinction. In a world that often feels mapped and measured, they offer a sense of mystery and majesty.

The Extinction of Giants: Climate, Catastrophe, and Humans

Perhaps the greatest mystery surrounding the prehistoric giants is not how they lived—but why they died. Extinctions have shaped life on Earth many times, and the disappearance of giants often coincides with environmental shifts and human expansion.

The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, 66 million years ago, is the most famous. A massive asteroid impact off the coast of modern-day Mexico caused wildfires, tsunamis, and a “nuclear winter” effect, dooming the non-avian dinosaurs and many other forms of life. Yet some creatures—birds, mammals, and crocodilians—survived and diversified.

In the more recent past, the end of the last Ice Age saw the extinction of many mammalian megafauna. As climates warmed and glaciers receded, habitats changed dramatically. But in many cases, these giants vanished shortly after humans arrived.

Were humans the primary cause of megafaunal extinction? It’s a complex debate. Some evidence supports overhunting by early humans—known as the “Blitzkrieg Hypothesis.” Other theories emphasize climate change or disease. In reality, it may have been a combination of pressures that proved too much for slow-reproducing giants to endure.

Their disappearance reshaped ecosystems and, in some places, left “ghosts”—trees that relied on now-extinct mammals for seed dispersal, or landscapes that seem oddly barren without their ancient engineers.

The Giants We Live With: Echoes of Prehistory

Though the great giants are gone, their legacy endures in the DNA of modern animals and in the very shape of our planet’s biosphere. Birds are living dinosaurs, direct descendants of theropods. Elephants, rhinos, and whales are echoes of the Cenozoic titans.

Modern conservation biology often draws upon paleontological insights. Understanding the extinction of past giants helps us protect endangered species today. Some scientists even propose “rewilding”—reintroducing species to restore ancient ecological roles once filled by megafauna.

Moreover, new technologies like CT scanning, 3D modeling, and ancient DNA analysis allow us to understand prehistoric giants more deeply than ever. We are no longer just guessing at their shape from bones; we are recreating their movements, studying their diseases, and even reconstructing their colors and social behavior.

Conclusion: The Timeless Allure of Ancient Giants

The giants of prehistory represent one of the most spectacular chapters in the history of life on Earth. They dominated their worlds, adapted to extremes, and shaped their environments in ways that still resonate today. Their bones are not just relics—they are monuments to evolution, survival, and the brutal poetry of natural history.

Their mystery is part of their charm. They are both known and unknowable, science and legend, fossil and myth. To study them is to glimpse not only the distant past but the future: a reminder of what life can become when nature’s hand deals out strength and scale in full measure.

And so we remain fascinated—not just because they were large, but because they were extraordinary. The enigmatic giants of prehistory challenge us to look backward with awe, forward with wisdom, and inward with humility, knowing that we are but recent arrivals in an ancient and wondrous saga.