Among all the questions that humanity has ever asked, few are as haunting—or as beautiful—as this: Are we alone? For centuries, humans have gazed at the night sky and wondered whether distant stars host other worlds like our own, worlds warmed by suns, bathed in water, and perhaps alive. This ancient curiosity has evolved into one of the greatest scientific quests of our time—the search for life beyond Earth.

Central to this search is a concept both simple and profound: the habitable zone, often called the Goldilocks Zone. It is the region around a star where conditions are “just right” for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface—not too hot, not too cold. Water, as far as we know, is the essential medium of life, the cradle in which chemistry becomes biology. Thus, the habitable zone marks the cosmic sweet spot where life as we understand it might flourish.

But the habitable zone is not a rigid boundary—it is a tapestry woven from light, heat, chemistry, and time. As our understanding of planets and stars deepens, we have learned that this zone can shift, stretch, and even exist in surprising places. It extends beyond the warmth of sunlight, into icy moons and hidden oceans, powered by tides and chemistry rather than starlight.

In exploring the habitable zone, we are not merely tracing circles around stars. We are tracing the contours of possibility itself—the delicate balance that allows worlds to awaken.

The Origins of the Idea

The concept of a habitable zone is older than modern astronomy. Ancient philosophers speculated that other worlds might exist, each with their own suns and inhabitants. Yet it was not until the scientific revolution that the idea took on measurable form.

In the 17th century, Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei shattered the medieval notion of an Earth-centered cosmos. The universe, they showed, was vast and filled with stars like our Sun. As telescopes improved, scientists began to suspect that many of these stars could host planets of their own.

The modern idea of a habitable zone emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, as astronomers and biologists sought to define the limits of life. They realized that for life to thrive, a planet must orbit within a range of distances where water remains liquid. If too close to the star, water evaporates into vapor; too far, it freezes into ice. Between these extremes lies the narrow band where oceans can exist—a potential oasis in the cosmic desert.

Carl Sagan, one of the most eloquent voices of modern science, often spoke of this balance. “Somewhere,” he wrote, “something incredible is waiting to be known.” The habitable zone became the stage on which that incredible possibility might unfold.

The Science of “Just Right”

To understand the habitable zone, we must first understand the interplay of energy between a star and its planet. A star radiates heat and light, warming its surroundings. The intensity of that radiation diminishes with distance, following a simple law of physics—the inverse square law.

The habitable zone, then, depends primarily on two factors: the star’s luminosity and the planet’s atmosphere. A more luminous star pushes its habitable zone farther out; a dimmer star draws it inward. Earth, for instance, occupies a perfect position around our Sun—roughly 150 million kilometers away—where the average temperature allows water to flow and clouds to form.

Yet distance alone does not determine habitability. A planet’s atmosphere acts as a thermal blanket, trapping heat through the greenhouse effect. Without it, Earth would be a frozen wasteland, with an average temperature below -15°C. With too much greenhouse gas, however, the planet overheats, as happened on Venus, where temperatures soar above 460°C.

Thus, habitability is a dance between star and atmosphere—a balance of radiation, reflection, and retention. The habitable zone is not a fixed distance but a dynamic range, shifting as stars age and planets evolve.

The Goldilocks Paradox

The “Goldilocks Zone” is an appealing metaphor, but reality is far more complex than a single ring around a star. A planet’s ability to support life depends on many intertwined variables—its mass, composition, magnetic field, rotation, and even the chemistry of its rocks and oceans.

Consider Mars and Venus, Earth’s closest neighbors. Both lie near the edges of the Sun’s habitable zone, yet both are hostile to life as we know it. Mars, small and geologically quiet, lost most of its atmosphere and surface water billions of years ago. Venus, with a thick carbon dioxide envelope, suffers from a runaway greenhouse effect that transformed it into an inferno.

Earth alone sits at the delicate intersection of conditions that sustain life—a stable orbit, protective magnetic field, moderate greenhouse effect, and active geology that recycles carbon through plate tectonics. This balance is so intricate that even small changes could have rendered our planet barren.

The paradox of the habitable zone, then, is that being “in the zone” is not always enough. A planet must not only lie within the right distance but also possess the right internal and atmospheric properties. The more we learn about exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars—the more we realize how rare and precious that balance might be.

Stars and Their Zones

Not all stars are created equal, and their differences profoundly shape the nature of their habitable zones.

Massive, hot stars—those of spectral types O, B, and A—shine brightly but live briefly. Their habitable zones lie far out, but their lifespans are so short (a few million years) that life would scarcely have time to evolve. Smaller, cooler stars—like K and M dwarfs—live for trillions of years, offering stability but posing other challenges.

M-dwarf stars, the most common in the galaxy, have habitable zones so close that planets orbit in mere days or weeks. This proximity often leads to tidal locking, where one side of the planet perpetually faces the star while the other remains in darkness. Moreover, M-dwarfs are prone to intense stellar flares, which can strip atmospheres and sterilize surfaces.

Yet even here, hope persists. A thick atmosphere or ocean could distribute heat and shield against radiation, allowing life to survive in twilight regions between day and night. In such worlds, eternal sunsets might illuminate alien seas—worlds neither day nor night, but something in between.

For Sun-like stars, the habitable zone stretches roughly from 0.95 to 1.7 astronomical units (AU), where one AU is the distance from Earth to the Sun. For cooler red dwarfs, it may lie at just 0.1 AU, while for hotter stars, it extends several AU outward. These zones shift over time as stars evolve, gradually brightening and altering the climates of their planets.

Planetary Conditions and the Role of Water

Liquid water is the cornerstone of habitability, not because it is the only solvent possible, but because it is unmatched in its versatility. Water dissolves a vast array of molecules, facilitates chemical reactions, and provides stability across a wide temperature range. It acts as a medium where atoms can mingle and self-organize into the building blocks of life.

A planet within the habitable zone must therefore be able to maintain surface pressure and temperature that allow water to remain liquid. Too little atmospheric pressure, and water boils away; too much, and it may exist only as superheated vapor. The balance depends on both gravity and composition.

Earth’s oceans, covering more than 70 percent of its surface, moderate temperature fluctuations and drive the carbon cycle that regulates climate. Planets lacking such stabilizing systems may oscillate between freezing and boiling extremes.

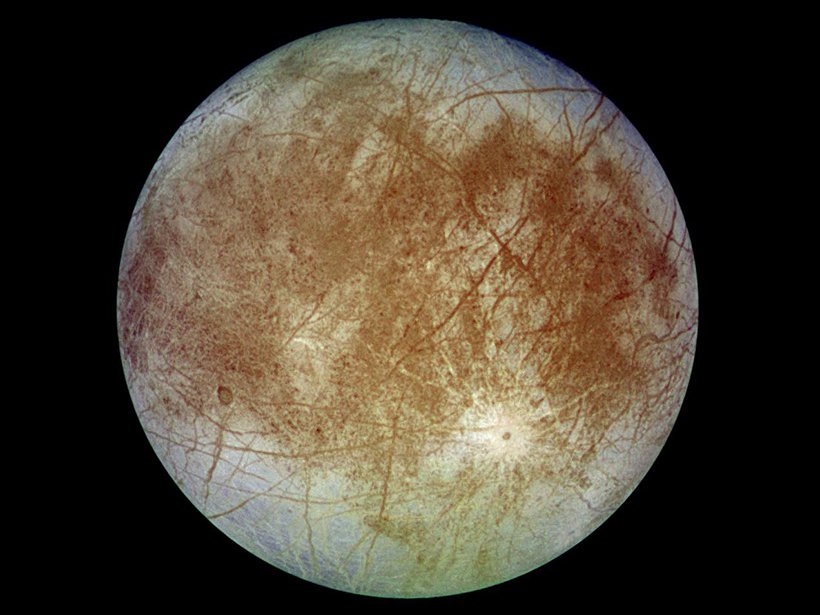

However, recent discoveries suggest that water—and perhaps life—might not require surface oceans at all. Moons like Europa and Enceladus, far outside the Sun’s traditional habitable zone, harbor subsurface oceans kept liquid by tidal heating. This revelation has expanded the definition of habitability beyond sunlight, into realms warmed by internal energy.

Beyond the Classic Habitable Zone

The traditional habitable zone focuses on surface conditions, but nature is rarely confined to simple boundaries. In recent years, scientists have proposed a broader, more nuanced view—one that includes “extended habitable zones” and “alternative biospheres.”

In icy moons of the outer solar system, such as Europa, Ganymede, Enceladus, and Titan, gravitational interactions with their parent planets generate internal heat. Beneath their frozen crusts lie oceans of liquid water, potentially rich in organic chemistry. Jets of vapor erupt from Enceladus’s south pole, hinting at hydrothermal activity similar to Earth’s deep-sea vents—places where life thrives without sunlight.

Even rogue planets, drifting through interstellar space without a star, might harbor life if they retain thick hydrogen atmospheres or internal heat from radioactive decay. In such worlds, life would exist in perpetual night, warmed from within rather than without.

The concept of habitability, then, is evolving. It is no longer a simple circle around a star but a spectrum of environments where energy, chemistry, and time intersect to create possibility.

The Search for Other Earths

With the advent of powerful space telescopes, humanity has entered an era of discovery unparalleled in history. The Kepler Space Telescope, launched in 2009, revolutionized our understanding of planetary abundance. It revealed that planets are common—perhaps more numerous than stars—and that many orbit within their stars’ habitable zones.

Among these discoveries are tantalizing candidates: Kepler-186f, Kepler-452b, and TRAPPIST-1e, to name a few. These worlds vary in size, orbit, and stellar type, but each offers a glimpse of what might be possible. The TRAPPIST-1 system, for instance, hosts seven Earth-sized planets, three of which lie within the habitable zone of a dim red dwarf.

However, identifying a planet in the habitable zone does not guarantee that it is habitable. Astronomers must also determine whether it has an atmosphere, what that atmosphere is made of, and whether it can sustain liquid water. This requires studying the faint light that passes through or reflects from the planet’s atmosphere—a technique known as spectroscopy.

In the coming decades, missions like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the upcoming Habitable Worlds Observatory will analyze the atmospheres of exoplanets in unprecedented detail. They will search for “biosignatures”—molecules such as oxygen, methane, and ozone that could indicate biological activity.

The Fragility of Habitability

The habitable zone is not a static paradise but a fleeting balance. Stars evolve, brightening over time, slowly pushing their habitable zones outward. Planets that are habitable today may become sterile tomorrow.

Earth itself will one day leave the Sun’s habitable zone. In about a billion years, as the Sun brightens, rising temperatures will evaporate Earth’s oceans, stripping its atmosphere and sterilizing its surface. Life may retreat underground or perish entirely. In the distant future, our once-blue planet will resemble Venus—hot, dry, and lifeless.

This cosmic fragility underscores how rare and transient habitability may be. Life depends not only on where a planet is, but when it is there. The habitable zone is a moving target, a window that opens briefly in cosmic time.

The Role of Planetary Systems

Planets do not exist in isolation. Their habitability depends on the architecture of their entire solar system—the presence of gas giants, asteroid belts, and orbital resonances. Jupiter, for example, has acted as both protector and destroyer for Earth. Its gravity deflects comets that might otherwise strike us, yet it may also have destabilized early planetary orbits.

Moons can also enhance habitability. Earth’s large Moon stabilizes the planet’s axial tilt, preventing extreme climate swings. Without it, Earth might experience chaotic seasons that could hinder the evolution of complex life.

Similarly, the presence of plate tectonics, magnetic fields, and volcanic recycling is crucial. These processes regulate atmosphere and temperature, shield life from radiation, and maintain a balance of gases. A habitable planet is not merely located in the right place—it must stay habitable through self-regulating feedback loops.

Redefining Life

As our exploration continues, we must confront a profound question: what if life does not require Earth-like conditions at all?

Our definition of habitability is rooted in our own biology, but life elsewhere could be built on different foundations. Could it exist in methane lakes on Titan, or in the acidic clouds of Venus, or within the supercritical carbon dioxide oceans of an exoplanet? Some scientists speculate about “silicon-based” or “ammonia-based” life—forms that operate under entirely different chemistries.

If such life exists, it may not inhabit the classical habitable zone at all. It could thrive in environments we consider deadly, invisible to our Earth-centric expectations. Expanding our definition of habitability is therefore not just scientific necessity—it is an act of humility, acknowledging that life might be far more diverse than we can imagine.

The Philosophical Horizon

The search for habitable worlds is more than an astronomical pursuit—it is a philosophical odyssey. It forces us to confront questions about our place in the universe and the nature of life itself.

If we find other living worlds, even simple microbial ones, it will transform our understanding of existence. Life will no longer be a cosmic accident, but a common thread woven through the fabric of the cosmos. If, on the other hand, the universe proves silent and barren, the rarity of life will make Earth infinitely precious—a fragile oasis amid infinite darkness.

Either way, the search ennobles us. It reminds us that we are part of a vast and evolving cosmos, connected by the same laws of physics that shape distant suns. The habitable zone becomes not just a region in space, but a metaphor for balance, for the conditions that allow consciousness to emerge and ask these very questions.

The Future of Discovery

In the next century, the study of habitability will deepen beyond imagination. Telescopes will capture direct images of Earth-like planets, revealing oceans, continents, and perhaps even weather patterns. Space probes will explore the icy moons of our solar system, drilling through crusts to sample alien seas. Artificial intelligence will sift through billions of stars, searching for the faint whispers of biological chemistry.

Meanwhile, humans will extend our own habitable zone. Lunar bases, Martian colonies, and space habitats will teach us how to create self-sustaining ecosystems beyond Earth. In doing so, we will not only seek other habitable worlds—we will become architects of habitability ourselves.

The boundary between natural and artificial habitability will blur. We will learn that life is not confined to the zones drawn by nature but can expand those zones through innovation and adaptation. The cosmos will become, in a sense, more alive because we are here to explore it.

The Cosmic Perspective

When viewed through the lens of deep time, the habitable zone becomes a fleeting shimmer of balance amid the chaos of creation. Stars are born, blaze for eons, and die; planets form, evolve, and perish. In this grand cycle, the conditions for life are both fragile and miraculous.

And yet, against these odds, life arose on one small world orbiting a middle-aged star in a spiral arm of an ordinary galaxy. From that humble beginning emerged beings capable of understanding the physics of starlight, mapping invisible orbits, and dreaming of other shores. The search for habitable zones is, in truth, the search for ourselves—reflected across the universe.

In every star we study, we glimpse a possibility. In every exoplanet, we see a mirror of our own world. The habitable zone is the threshold between the known and the possible, the thin line between chemistry and consciousness.

The Eternal Quest

The habitable zone is not just a scientific construct—it is the symbol of life’s persistence. It embodies the universe’s capacity to nurture, to balance, to create. As we continue our search, we may find that the cosmos is teeming with worlds bathed in light and warmth, each with its own stories, oceans, and skies. Or we may find that life is rare, a singular flame flickering in the cosmic dark.

Either way, the journey is worth every effort, for in seeking other worlds, we rediscover our own. The quest for habitability reminds us that the Earth itself is a miracle—a world perfectly poised in its own fragile zone.

As long as there are minds to wonder and eyes to look upward, the question will endure. Somewhere, orbiting a distant sun, another blue world may be turning beneath familiar skies. And when we finally find it, we will understand that the universe has been waiting—not to reveal itself, but to remind us that we were part of it all along.

The habitable zone is not merely where life might exist—it is where life begins to imagine, to explore, and to dream. It is the threshold between silence and song, between darkness and the dawn of understanding. And as we continue to search the stars, we carry with us the light of that eternal dream: that somewhere out there, life is looking back.