Long before the temples of marble gleamed beneath the sun, before philosophers debated truth in Athens or soldiers stood proud at Thermopylae, there was an age when gods still walked among mortals. It was an era when courage was not just admired—it was divine currency. The Greeks called it The Heroic Age, a golden time that bridged heaven and earth, myth and history, dream and memory.

This age was not merely a chapter in mythology—it was the heartbeat of Greek imagination. The stories born from this era shaped the soul of a civilization that would one day give birth to Western thought. Heroes strode the world with divine blood in their veins and destiny burning in their hearts. They fought monsters that embodied chaos and built kingdoms that became legend. Every tale was a mirror reflecting human passion, ambition, and the eternal longing to transcend mortality.

The Heroic Age of Greece was not just about strength or conquest—it was about meaning. It asked what it means to be human in a world touched by the divine, and whether greatness is born from favor of the gods or the fire within one’s soul.

When Gods Ruled from Olympus

In the beginning, the world was ruled by the Olympian gods—immortal, radiant, and yet deeply human in their emotions. From their golden thrones upon Mount Olympus, Zeus and his divine kin watched over the affairs of mortals, intervening when whim or passion demanded it.

Zeus, the thunder-wielding king of the gods, was the arbiter of justice and order, but also the father of heroes. Through unions—sometimes gentle, sometimes forceful—with mortal women, he sired many of the demigods who would shape the Heroic Age. Hera, his queen, was the goddess of marriage but also the tormentor of Zeus’s mortal offspring, driving many heroes toward their tragic fates.

Athena, goddess of wisdom and war, became the divine patron of cunning and valor. Apollo’s music and prophecy guided kings, while Poseidon’s tempests tested the endurance of sailors and warriors alike. Even Aphrodite and Ares—love and war—seemed to conspire to stir the passions that gave rise to glory and ruin.

The Olympians were more than deities—they were the embodiment of human nature magnified to the scale of eternity. Their jealousies, loves, and rivalries echoed through the lives of mortals, binding heaven and earth in one great story.

The Blood of the Gods: Birth of the Demigods

The Heroic Age began when divine blood mingled with mortal flesh. These children of gods and humans were extraordinary—stronger, braver, and more ambitious than any ordinary man. Yet they also bore the burden of their dual nature, torn between the perfection of Olympus and the frailty of the earth.

From this sacred lineage came heroes like Heracles, Achilles, Perseus, and Helen of Troy—each a symbol of the heights and depths of the human spirit. They were destined for greatness, but greatness in Greece was never without tragedy.

To be heroic was to live intensely and die gloriously. The Greeks believed that the gods envied human mortality—for only mortals could seize fleeting beauty, love, and courage in the face of death. Thus, the Heroic Age was not about immortality—it was about earning remembrance.

Perseus: The Slayer of Monsters

Long before Troy’s walls were built, a young man named Perseus set out to challenge fate itself. Born of Danaë, who was imprisoned by her father King Acrisius to avoid a prophecy of doom, Perseus came into the world through divine intervention. Zeus appeared to Danaë as a shower of golden light, and from their union came the hero destined to change the world.

Cast into the sea as an infant, Perseus survived through the favor of the gods. When he came of age, he was tasked with an impossible quest: to slay Medusa, the monstrous Gorgon whose gaze turned men to stone. With Athena’s mirrored shield, Hermes’ winged sandals, and a sword forged by Hephaestus, Perseus embarked on his perilous journey.

In the cavern where shadows breathed and serpents hissed, Perseus crept upon Medusa as she slept. Using the shield to see her reflection, he struck with a single, perfect blow. From her blood sprang Pegasus, the winged horse, and the hero returned victorious.

But Perseus’ journey did not end with conquest. On his return, he saved Andromeda, a princess chained to a rock as sacrifice to a sea monster. His courage and love united them, and together they founded dynasties that would one day lead to heroes like Heracles.

Perseus’ story is not just of valor—it is the triumph of cleverness, faith, and divine aid over terror. It marks the first glimmer of human mastery over chaos, a theme that would echo throughout the Heroic Age.

Heracles: The Strength of Suffering

Among all the heroes, none was more celebrated—or more tormented—than Heracles, the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Alcmene. Even before his birth, Hera’s jealousy burned against him, and from his first breath, his life was a test of endurance.

Heracles’ strength was unmatched, yet his heart bore endless pain. Driven mad by Hera’s wrath, he killed his wife and children in a moment of divine madness. Stricken with horror and guilt, he sought purification through service to King Eurystheus, who imposed upon him twelve labors—impossible tasks meant to break his spirit.

He faced the Nemean Lion, whose hide no weapon could pierce; the Hydra, whose heads multiplied when severed; and the Augean Stables, which he cleansed by diverting rivers. He captured the Ceryneian Hind, the Erymanthian Boar, and the golden apples of the Hesperides. Each labor was more than a feat of strength—it was a journey of redemption.

In Heracles, the Greeks saw the essence of the human struggle: to endure suffering and rise again. His labors symbolized the cleansing of the soul through toil, courage, and perseverance. When his mortal body finally perished in flames, Zeus lifted him to Olympus, granting him immortality. Heracles became both god and man—an eternal bridge between pain and glory.

Theseus: The Founder of Civilization

While Heracles embodied brute strength, Theseus represented intellect, justice, and the power of civilization. The son of King Aegeus and Aethra, Theseus grew up unaware of his royal blood until he lifted a buried stone to retrieve his father’s sword and sandals—a test of lineage and destiny.

His most famous feat was his journey to Crete to slay the Minotaur, a monstrous creature imprisoned in the Labyrinth by King Minos. With the help of Ariadne, who loved him and gave him a thread to find his way back, Theseus entered the maze and faced the beast. His victory over the Minotaur was more than a triumph of courage—it symbolized the victory of order over chaos, of reason over instinct.

Theseus’ legacy extended beyond his heroic deeds. He unified the scattered villages of Attica into the great city of Athens, laying the foundation for democracy and civic unity. He was both warrior and statesman—a symbol of humanity’s evolution from myth to reason.

Jason and the Argonauts: The Voyage of Brotherhood

No tale of the Heroic Age captures the spirit of adventure quite like that of Jason and the Argonauts. Jason, the rightful heir to the throne of Iolcus, was sent by his uncle Pelias to retrieve the Golden Fleece—a treasure guarded in a distant land at the edge of the world.

He assembled a crew of heroes—the Argonauts—each a legend in his own right: Heracles, Orpheus, Atalanta, Castor, and Pollux among them. Their ship, the Argo, was a vessel of destiny, and their journey became a symbol of human unity in the face of impossible odds.

With the aid of the sorceress Medea, who fell in love with him, Jason overcame trials that tested both his courage and his heart. He yoked fire-breathing bulls, sowed dragon’s teeth that sprouted into warriors, and claimed the fleece guarded by a sleepless serpent.

But triumph carried a curse. Medea’s love turned to vengeance when Jason betrayed her, and their tragedy became a haunting reminder that heroism often walks hand in hand with betrayal and loss.

The voyage of the Argo remains a metaphor for every human journey—a quest for something precious, a struggle against chaos, and a lesson that even victory can demand a heavy price.

Achilles and the Rage of Troy

Of all the heroes, none burned brighter—or died younger—than Achilles. The son of Peleus and the sea goddess Thetis, Achilles was destined to be the greatest warrior of his age. Yet fate offered him a cruel choice: a long, obscure life or a short life crowned with eternal glory.

He chose glory.

When Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, was taken from Sparta to Troy, the Greek kingdoms united to bring her back. Achilles sailed with them, his armor gleaming like fire, his wrath unmatched. In the long war that followed, he became both savior and destroyer.

His story, immortalized in Homer’s Iliad, is not one of triumph but of tragedy. Achilles’ fury against Agamemnon, who dishonored him, withdrew his strength from the battlefield and cost countless lives. Only when his beloved friend Patroclus was slain did Achilles return, his grief transforming into vengeance.

He faced Hector, the noble defender of Troy, and slew him in a duel that echoed through eternity. Yet even in victory, Achilles’ heart was broken. Soon after, an arrow guided by Apollo struck his heel—the only mortal part of him—and he fell, fulfilling his fate.

Achilles’ story is the very soul of the Heroic Age: the defiance of death, the pursuit of eternal remembrance, and the understanding that glory and doom are intertwined.

Odysseus: The Wanderer of Many Wiles

Where Achilles embodied passion, Odysseus embodied intellect. The king of Ithaca was known not for brute strength but for cunning and eloquence. In the Trojan War, his mind proved as deadly as any sword—he conceived the idea of the wooden horse that led to Troy’s downfall.

Yet his true legend began after the war, in his ten-year journey home—a voyage chronicled in Homer’s Odyssey. Odysseus faced storms, monsters, and temptations that tested not only his survival but his soul.

He blinded the Cyclops Polyphemus, resisted the Sirens’ deadly songs, and descended into the underworld itself. His encounters with Circe, Calypso, and the wrath of Poseidon turned his voyage into a profound odyssey of endurance and transformation.

When he finally returned to Ithaca, weary and disguised as a beggar, he found his home overrun by suitors vying for his wife Penelope. With quiet precision, he reclaimed his throne and his life.

Odysseus’ tale speaks to the endurance of human will. His journey is every person’s journey—the search for home, meaning, and identity in a world of endless trials.

Helen: The Beauty That Launched a Thousand Ships

In the tapestry of myths, Helen of Troy stands as both muse and mystery. Daughter of Zeus and Leda, she was said to be the most beautiful woman who ever lived. Her beauty was not just physical—it was a force of destiny.

When Paris, prince of Troy, chose Aphrodite as the fairest goddess, he was granted Helen’s love as his reward. But Helen was already married to Menelaus, king of Sparta. Her abduction—or elopement—ignited the greatest war the ancient world had ever known.

The Greeks besieged Troy for ten long years, not merely for Helen but for honor, pride, and fate itself. To the ancients, Helen symbolized the power of beauty and desire—the forces that could move nations and topple kings. Yet she was also a victim of divine manipulation, a pawn in the endless games of gods and men.

Her story endures because it captures a universal truth: that beauty and destruction, love and ruin, often spring from the same source.

The Fall of Troy: End of the Heroic Age

The fall of Troy marked the twilight of the Heroic Age. The city’s walls, built by Poseidon himself, fell not to might but to cunning—the Trojan Horse, a symbol of human ingenuity and deceit.

As the Greeks stormed the city, fires rose to the heavens, and the cries of both victors and vanquished filled the night. Priam, king of Troy, was slain before his altar. Aeneas, guided by the gods, fled to found a new destiny that would one day give birth to Rome.

The gods themselves turned away from the world of men, their golden age fading into memory. The heroes who survived returned home to find their kingdoms broken, their hearts weary. The great generation was gone, leaving only stories—songs sung by poets who preserved their names for eternity.

The Legacy of the Heroic Age

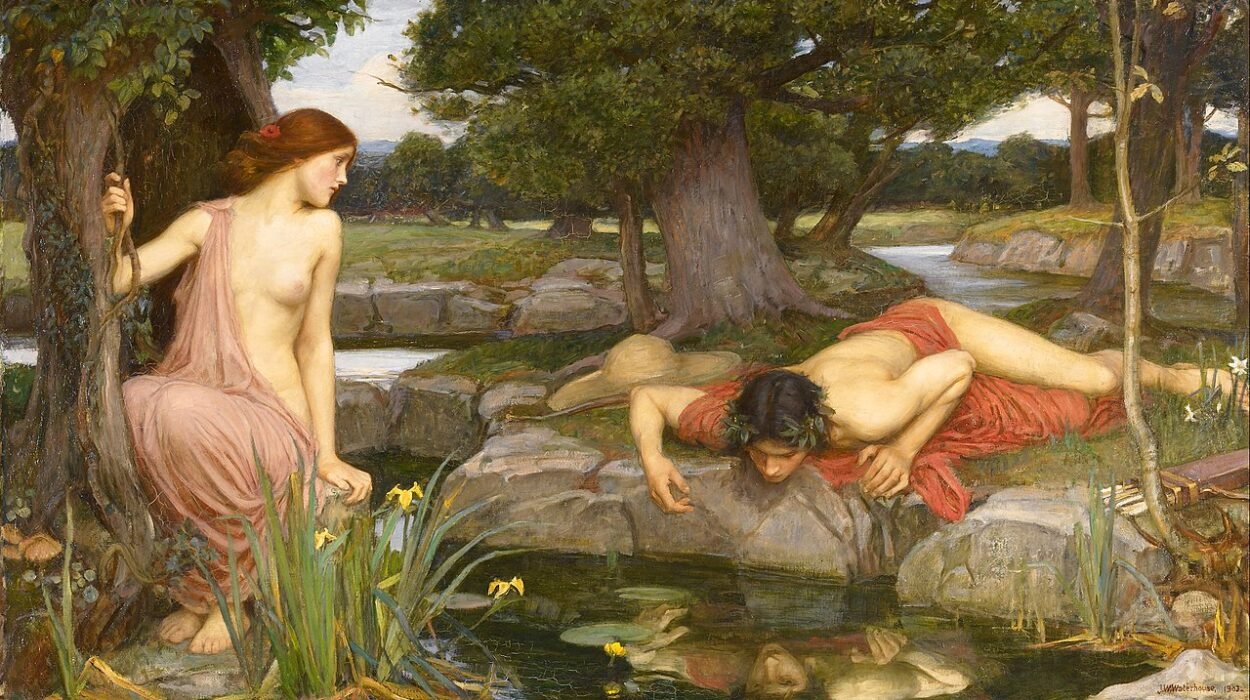

Though centuries have passed, the Heroic Age remains immortal. Its myths are not relics—they are living truths that continue to shape art, literature, and philosophy. From Homer’s epics to modern cinema, these stories endure because they speak to something timeless: the struggle between destiny and choice, pride and humility, mortality and immortality.

The Greeks believed that to die with glory was to achieve a kind of eternal life. Through their myths, they granted their heroes that immortality. Heracles, Achilles, Odysseus, and all who dared to dream beyond the mortal span still live in our imagination.

Physics may describe the universe’s laws, but mythology describes its soul. The Heroic Age of Greece was that bridge between both—a realm where gods shaped men, and men, in turn, defined the divine.

The Eternal Fire

The Heroic Age may have ended in ashes, but its flame has never died. It burns in every act of courage, in every dream that defies limitation, in every soul that reaches for something beyond itself.

For though the gods may have retreated to myth, the hero endures. The Heroic Age lives on wherever the human heart dares to confront the impossible, to struggle, to love, and to rise again.

And perhaps that is the truest meaning of all: that we, too, are children of that age—forever seeking the divine within ourselves, forever striving to turn our brief mortal spark into something worthy of legend.