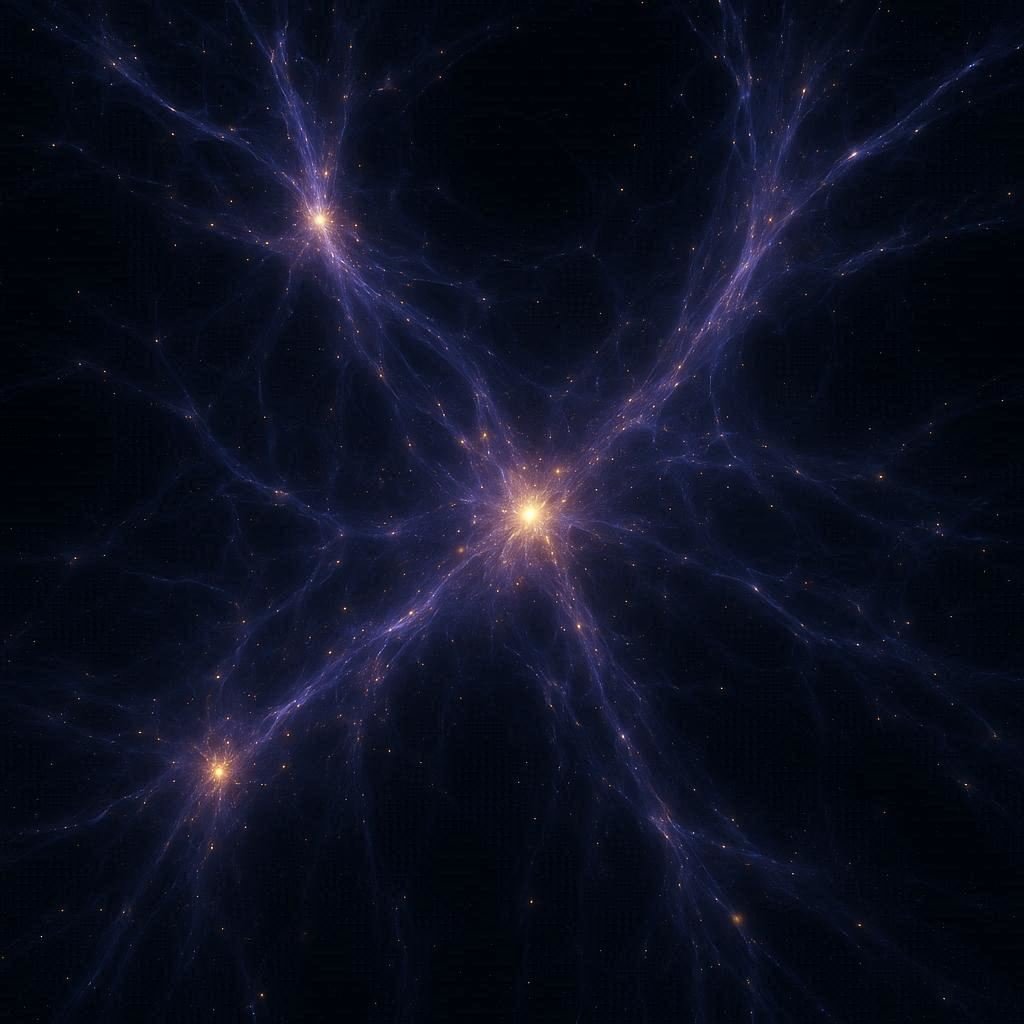

When we gaze up at the night sky, we see points of light scattered like diamonds on black velvet—beautiful, distant, and seemingly random. Yet what appears as chaos to the naked eye hides an astonishing order. Beyond the stars, beyond the Milky Way, and beyond even the clusters of galaxies we can see through telescopes, the universe reveals a breathtaking tapestry—a vast, interconnected cosmic web made of filaments, voids, and superclusters.

This immense architecture is the hidden skeleton of the cosmos, the largest structure ever discovered, stretching billions of light-years across. It is where gravity and time weave the raw material of creation into intricate patterns, where galaxies form along invisible threads, and where empty spaces between them hold mysteries as deep as the stars themselves.

The story of the cosmic web is not just about galaxies and matter. It is about the profound beauty of order emerging from chaos, about the universe sculpting itself from the afterglow of the Big Bang, and about humanity’s quest to understand a structure so immense that it dwarfs everything we know.

The Cosmic Blueprint

To truly grasp the hidden structure of the cosmos, we must step back—far back. Imagine zooming out from Earth until our planet vanishes, then the Sun, then the entire Milky Way. As we pull farther away, millions of other galaxies come into view, forming clusters that gather like cosmic cities connected by faint bridges of light. These bridges—thin, luminous tendrils of galaxies and dark matter—are known as filaments. Between them lie vast, silent voids—immense regions of near emptiness stretching hundreds of millions of light-years wide.

When seen from this grand perspective, the universe looks like a colossal spiderweb or a network of glowing neurons. The galaxies are not sprinkled evenly through space; they align along these filaments, drawn together by the invisible hand of gravity acting on dark matter.

The existence of this structure was not always known. For centuries, humans believed the universe was static and uniform. Even after Edwin Hubble discovered in the 1920s that the universe was expanding and filled with galaxies, most astronomers imagined them distributed more or less evenly. But as telescopes grew stronger and sky surveys mapped more galaxies, a new picture emerged—one that revealed astonishing cosmic patterns.

The Discovery of the Cosmic Web

The realization that the universe has structure on the largest scales came only in the late 20th century. In the 1970s and 1980s, astronomers began conducting massive redshift surveys—projects that measured how far away thousands of galaxies were and where they were located in three-dimensional space. When the data was plotted, the results were stunning.

Galaxies were not scattered randomly at all. Instead, they appeared to form walls, filaments, and clusters surrounding enormous empty voids. The universe resembled a frothy foam, like bubbles clustering together—dense walls of galaxies surrounding hollow regions of space.

One of the most famous early maps was the CfA Redshift Survey, which revealed the so-called “Great Wall,” an immense structure of galaxies stretching over 500 million light-years. Later surveys uncovered even larger features, such as the Sloan Great Wall and the Hercules–Corona Borealis Great Wall—structures so vast they challenge our understanding of cosmic scale.

The more we looked, the clearer it became: the universe is a web, and galaxies are its shining nodes. What we once thought of as the void between stars is, in truth, filled with patterns so vast and elegant that they redefine our sense of existence.

The Birth of Structure from the Big Bang

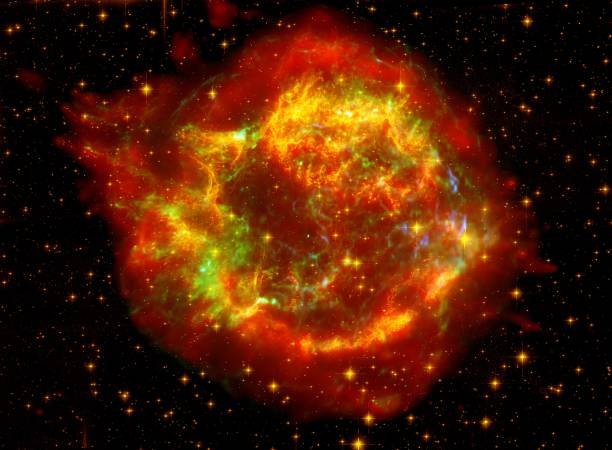

How did this intricate cosmic web come into being? The answer lies in the very beginning of time—in the first moments after the Big Bang.

Roughly 13.8 billion years ago, the universe was a hot, dense sea of energy. Tiny quantum fluctuations—microscopic ripples in that early plasma—were stretched across space as the universe expanded. These minute irregularities in density, one part in a hundred thousand, became the seeds of all cosmic structure.

As the universe cooled, gravity began to amplify those ripples. Slightly denser regions pulled in more matter, becoming even denser over time. Hydrogen and helium gas flowed toward these gravitational wells, forming vast sheets and filaments of matter. The empty regions between them—areas where matter was scarce—expanded into the immense cosmic voids we see today.

Billions of years later, these filaments became the highways of creation, channels along which gas flowed to form galaxies and stars. The cosmic web, in a sense, is the frozen memory of those ancient quantum fluctuations—patterns etched into the fabric of space-time itself.

Dark Matter: The Invisible Sculptor

The visible universe—the stars, planets, gas, and dust—accounts for less than 5% of all cosmic matter. The rest is mostly dark matter, a mysterious substance that neither emits nor absorbs light but exerts gravity nonetheless.

It is dark matter that forms the invisible scaffolding of the cosmic web. In the early universe, it was dark matter that began to clump under gravity, forming dense knots and filaments. Ordinary matter, made of atoms, followed this invisible framework, cooling and condensing to form galaxies where dark matter was most concentrated.

Computer simulations, such as the Millennium Simulation and the Illustris Project, have vividly shown how dark matter shapes the universe. When scientists feed the laws of physics and the initial conditions of the Big Bang into these simulations, a web of filaments and voids naturally emerges—remarkably similar to what astronomers observe.

The conclusion is both humbling and exhilarating: we are living in a universe whose grand design is guided by something we cannot see, touch, or measure directly. Dark matter, silent and unseen, is the cosmic sculptor behind the galaxies, the architect of structure, and the unseen hand that pulls the universe into form.

Filaments: The Highways of the Universe

If galaxies are the cities of the cosmos, then filaments are the intergalactic highways connecting them. These filaments are immense strands of dark matter and gas, often hundreds of millions of light-years long and several million light-years wide. Along these vast tendrils, galaxies form and cluster, pulled together by the shared gravity of the filament.

Astronomers have begun to detect these filaments directly, not just through galaxies but through the faint glow of intergalactic gas. Using powerful instruments like the Keck Observatory and the Very Large Telescope, scientists have observed hydrogen gas illuminated by distant quasars—massive black holes whose light reveals the otherwise invisible filaments.

These cosmic bridges are not static. Matter flows along them toward the densest regions—superclusters and galaxy clusters—where gravity is strongest. In this way, filaments act as the veins of the universe, channeling the raw material of stars and galaxies into larger cosmic structures.

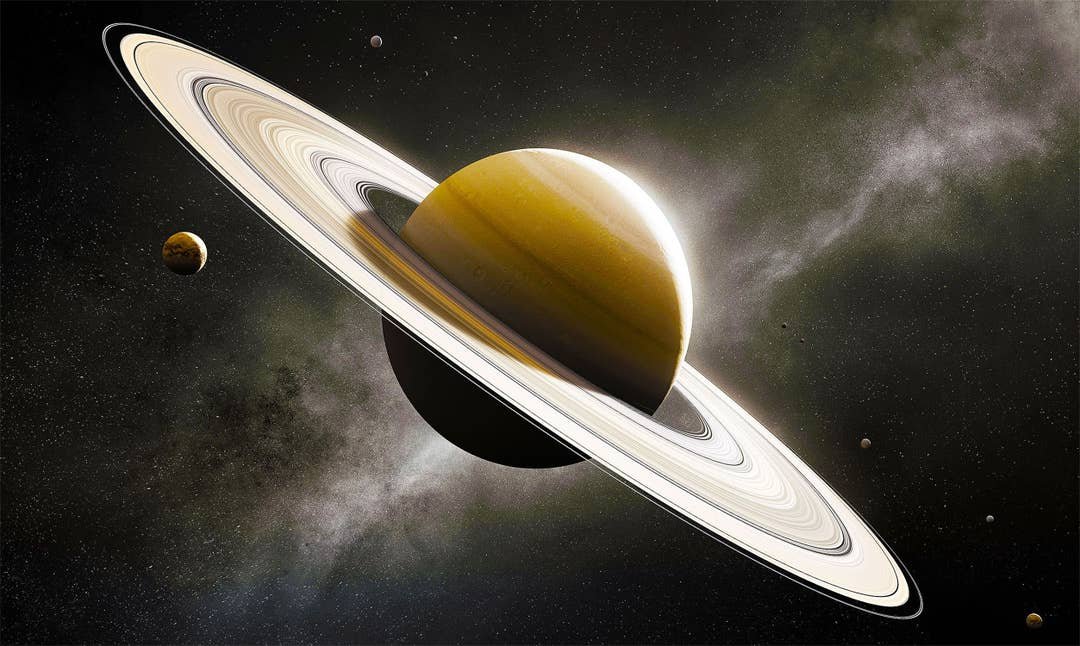

Even our own Milky Way is not isolated. It resides within a filament of the cosmic web, slowly drifting toward a massive supercluster known as Laniakea—a grand gravitational basin encompassing hundreds of thousands of galaxies.

Voids: The Silent Heart of the Cosmos

Between the glowing filaments lie vast voids—regions where galaxies are scarce and the density of matter is astonishingly low. These cosmic voids are the great silences of the universe, immense expanses of near-nothingness spanning hundreds of millions of light-years.

Yet these voids are not entirely empty. They contain a thin mist of hydrogen gas, traces of dark matter, and the faint echo of the cosmic microwave background—the afterglow of the Big Bang. Some even harbor a few isolated galaxies, lonely wanderers adrift in the cosmic sea.

Voids are as crucial to the universe’s structure as the filaments themselves. They expand faster than the denser regions, pushing galaxies into walls and filaments like soap bubbles clustering together. The result is a delicate balance between gravity’s pull and the universe’s expansion—a dance that sculpts the cosmic web’s intricate geometry.

Studying these voids gives cosmologists clues about dark energy, the mysterious force driving the universe’s accelerated expansion. Because voids are sensitive to the rate at which space itself expands, they serve as natural laboratories for understanding the fate of the cosmos.

Superclusters: The Empires of Galaxies

Where filaments intersect, the universe forms its grandest structures: superclusters. These are immense gatherings of galaxy clusters—cosmic metropolises connected by filaments and surrounded by voids.

Our own Milky Way belongs to a smaller cluster called the Local Group, which, in turn, is part of the Virgo Supercluster. But this structure itself is only a small section of something much greater—the Laniakea Supercluster, an enormous region spanning 500 million light-years and containing about 100,000 galaxies.

Discovered in 2014 by astronomer R. Brent Tully and his team, Laniakea (meaning “immense heaven” in Hawaiian) redefined our cosmic address. Within it, galaxies flow like rivers along gravitational currents toward a central region known as the Great Attractor—a dense nexus of matter whose pull organizes the motion of galaxies over unimaginable distances.

Beyond Laniakea lie even larger structures, like the Shapley Supercluster and the Hercules–Corona Borealis Great Wall. The latter stretches over 10 billion light-years—so vast that light itself would take nearly the entire age of the universe to cross it. These behemoths challenge our understanding of cosmic uniformity, hinting that the universe may be even more complex and interconnected than we realize.

The Role of Gravity and Expansion

The cosmic web is a delicate interplay between two opposing forces: gravity and expansion. Gravity pulls matter together, forming clusters and filaments, while the expansion of the universe pushes matter apart, enlarging the voids between them.

In the early universe, gravity had the upper hand, allowing matter to collapse into the structures we see today. But over time, as dark energy began to dominate, the expansion accelerated, stretching space itself and widening the gaps between filaments.

This ongoing tension gives rise to the dynamic architecture of the cosmos—a universe forever caught between creation and dispersal, cohesion and dissolution. Each galaxy, cluster, and filament is a monument to this eternal struggle, frozen in time yet evolving with every heartbeat of cosmic expansion.

Seeing the Invisible: Mapping the Cosmic Web

How do we map something so immense and mostly invisible? Astronomers have developed ingenious ways to trace the cosmic web using both direct and indirect observations.

Galaxies act as luminous tracers, outlining the underlying dark matter skeleton. By mapping their positions and redshifts—the stretching of light caused by cosmic expansion—astronomers can reconstruct the three-dimensional structure of space.

Other techniques use the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the faint afterglow of the Big Bang. Tiny distortions in this ancient light reveal how matter was distributed in the early universe, allowing scientists to trace the seeds of today’s structures.

More recently, gravitational lensing—where light from distant galaxies bends around massive structures—has provided a direct view of dark matter’s distribution. These cosmic fingerprints allow us to visualize the otherwise invisible threads connecting galaxies across billions of light-years.

Each new map of the cosmic web is a revelation—a reminder that we live inside an intricate, evolving masterpiece.

The Universe as a Living Network

When scientists look at the large-scale structure of the universe, they are often struck by how much it resembles a living system. Computer visualizations of the cosmic web bear a haunting resemblance to the neural network of the human brain.

Both are complex, interconnected systems optimized for efficiency. In the brain, neurons connect through synapses to transmit information. In the universe, galaxies connect through filaments to transfer matter and energy. Remarkably, studies have shown that the distribution of galaxies and dark matter shares similar mathematical patterns to the distribution of neurons and synapses.

It is as if the universe itself has a kind of cosmic intelligence—a vast network of connections spanning across unimaginable distances. This does not mean the universe is literally conscious, but it does suggest that nature, from the smallest scale to the largest, follows similar principles of organization.

The cosmic web is, in a sense, the universe’s way of thinking—a self-organizing pattern through which matter, energy, and information flow.

The Hidden Beauty of Nothingness

In the silent vastness of cosmic voids lies an unexpected beauty. The emptiness is not a failure of creation but a necessary balance—a counterpoint that gives meaning to structure. Without the voids, the filaments could not exist; without darkness, light would lose its contrast.

These regions of “nothingness” are crucial to the evolution of galaxies. As voids expand, they push matter toward the filaments, fueling star formation and shaping the cosmic landscape. The voids are the breath between the notes of the universe’s symphony, the pauses that allow the melody of matter to be heard.

Even in their emptiness, they whisper stories of expansion, gravity, and time. In their silence, they remind us that absence can be as profound as presence.

The Universe in Motion

The cosmic web is not static—it is alive with motion. Galaxies stream along filaments toward superclusters, drawn by the gravitational pull of unseen masses. The entire structure evolves, stretching and shifting as the universe expands.

Superclusters themselves drift through the cosmic ocean, slowly merging or separating over billions of years. Some may one day form colossal “mega-structures,” while others will fade as dark energy continues to drive expansion.

Our own galaxy participates in this vast migration, gliding along gravitational currents toward the Great Attractor, and beyond it, perhaps toward the Shapley Supercluster. On cosmic scales, our motion is part of an intricate ballet—a slow, majestic dance choreographed by gravity itself.

The Enduring Mysteries

Despite decades of research, many questions remain. What exactly is dark matter made of? What role does dark energy play in shaping the cosmic web? Are there even larger structures beyond what we can observe—superwalls spanning unimaginable distances?

Some cosmologists wonder whether the cosmic web is the ultimate structure or just one layer in a grander hierarchy. Could our universe itself be a filament in a higher-dimensional multiverse? These questions push the boundaries of science and imagination alike.

Yet even as we explore, the cosmic web continues to expand, forever stretching beyond our reach. Its edges mark the horizon of our understanding—a horizon we chase but may never cross.

Our Place in the Cosmic Web

Amid all this immensity, where do we fit? The answer is humbling and uplifting all at once. We are tiny, yes—an infinitesimal spark within one galaxy among trillions. Yet we are also part of the grand design. The atoms in our bodies were forged in stars that lie along those very filaments. The light that reaches our eyes has traveled through the vast corridors of the cosmic web.

We are not outsiders looking at the universe—we are participants within it, woven from the same cosmic threads. Our existence, our thoughts, our very consciousness are the universe reflecting upon itself.

To study the cosmic web is to study our own origin—to see the pattern that birthed both galaxies and life. It is to glimpse the architecture of eternity and recognize that the same laws shaping galaxies also shaped us.

The Poetry of the Infinite

The hidden structure of the cosmos is more than a scientific revelation—it is a work of art. The filaments, voids, and superclusters form a cosmic poem written in the language of gravity and light.

Every filament is a sentence; every cluster, a word; every void, a pause in the rhythm of creation. The universe is not a cold machine but a living, breathing symphony—a vast and eternal masterpiece that invites us to wonder.

When we map the cosmic web, we are not just charting matter—we are tracing the veins of existence itself. We are learning how chaos gives birth to order, how emptiness gives rise to form, and how something as immense as the universe can emerge from a whisper in the quantum vacuum.

In the end, the cosmic web teaches us that everything is connected. The galaxies that twinkle billions of light-years away are not distant strangers but parts of a single, unified whole.

The same invisible filaments that bind the cosmos also bind us—to the stars, to time, and to the very fabric of being.

The Eternal Wonder

As we stand beneath the night sky, it is easy to feel small. Yet within that smallness lies something extraordinary—the capacity to understand the infinite.

Through physics, astronomy, and imagination, we have begun to unveil the universe’s hidden skeleton, to see the filaments of light and shadow that give structure to everything we know. And though our understanding is still incomplete, each discovery brings us closer to a profound truth: that we are living inside a masterpiece so vast that it defies comprehension, yet so elegant that it feels inevitable.

The cosmic web is not just a structure—it is a story. A story of birth and expansion, of gravity and light, of silence and creation. It is the universe’s greatest work of art—and we, as observers and participants, are both its subjects and its authors.

The filaments stretch. The voids expand. The galaxies dance. And through it all, one question endures—a question as infinite as the web itself:

What does it mean to be part of something so boundless, so ancient, and so beautiful?

To gaze into the cosmic web is to glimpse the face of eternity—and to realize that, somehow, it is looking back at us.