Among all the planets in our Solar System, none wears its majesty more visibly than Saturn. Its luminous rings stretch across hundreds of thousands of kilometers, shimmering like the celestial crown of a cosmic monarch. Yet what truly completes that crown—what makes Saturn not merely beautiful but wondrous—are its moons. Over 140 confirmed moons orbit this gas giant, each one unique, mysterious, and scientifically profound. Together they form a miniature solar system, a grand orchestra of icy worlds, rocky fragments, and dynamic forces playing in harmony around a golden sphere.

The moons of Saturn are more than companions; they are storytellers. They carry within their orbits the history of the Solar System’s formation, the clues to life’s potential beyond Earth, and the evidence of cosmic processes that continue to shape worlds in the outer dark. Some are frozen wastelands, others volcanic infernos, and a few harbor oceans of liquid water beneath their icy crusts—perhaps the most promising abodes for life beyond our home planet.

To study Saturn’s moons is to explore a gallery of nature’s finest artistry. From the dazzling reflectivity of Enceladus to the haze-wrapped mystery of Titan, from the tumbling chaos of Hyperion to the shepherd moons that sculpt Saturn’s rings, each world is a gem—a distinct jewel in the cosmic crown.

The Formation of Saturn’s Moons

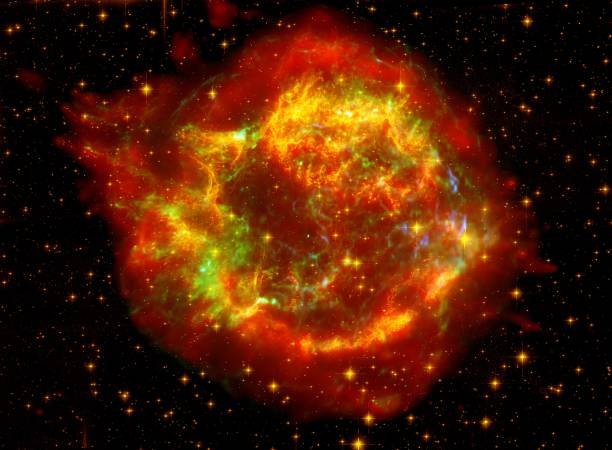

The story of Saturn’s moons begins in the earliest epoch of the Solar System, roughly 4.5 billion years ago. As the young Sun ignited and the planets coalesced from a swirling disk of gas and dust, Saturn—being one of the giant planets—became encircled by a smaller disk of its own. Within this circumplanetary disk, ice and rock collided, merged, and accreted to form moons, much as planets formed around the Sun.

Some of Saturn’s moons likely formed alongside the planet itself, while others were captured later. Irregular satellites, those with highly inclined or eccentric orbits, may be ancient asteroids or Kuiper Belt objects snared by Saturn’s immense gravity. These captured bodies tell of a Solar System filled with motion and exchange, where even massive worlds borrow from their surroundings.

Over billions of years, tidal forces, collisions, and gravitational resonances have reshaped Saturn’s moon system. Moons merged, others fractured, and some became locked in synchronous orbits. The result is the complex hierarchy we see today—a family of worlds orbiting a gas giant that itself orbits the Sun, a cosmic nesting doll of motion and energy.

Titan: The Misty Giant

Dominating Saturn’s retinue is Titan, its largest moon and one of the most intriguing worlds in the Solar System. Titan is larger than the planet Mercury and second only to Jupiter’s Ganymede in size. Yet what truly distinguishes it is its thick, orange atmosphere—a shroud of nitrogen and methane that gives Titan the appearance of a frozen, alien Earth.

Titan’s atmosphere, first detected by Earth-based telescopes and later explored in detail by the Cassini-Huygens mission, is both ancient and active. It is composed mostly of nitrogen (like Earth’s) but contains a significant amount of methane, which continuously breaks down under sunlight. To maintain this methane, Titan must possess reservoirs replenishing it—perhaps through cryovolcanism or subsurface processes.

Beneath its hazy skies lies a landscape of astonishing diversity. The Huygens probe, which landed on Titan in 2005, revealed river channels, pebbles of ice, and plains of frozen hydrocarbons. Cassini’s radar images later uncovered vast lakes and seas of liquid methane and ethane near the poles—bodies of liquid that behave much like Earth’s water, sculpting valleys and coasts. Clouds drift across Titan’s skies, and methane rain falls to the surface. It is, in a sense, the only other place in the Solar System where a liquid cycle—analogous to our water cycle—actively shapes the terrain.

Beneath Titan’s icy crust lies yet another wonder: a global ocean of water mixed with ammonia, hidden tens of kilometers below the surface. This ocean, kept warm by tidal heating, could harbor the chemistry essential for life. Titan is thus a world of paradoxes: alien yet familiar, frigid yet dynamic, and, perhaps, lifeless yet full of the ingredients life requires.

Enceladus: The Shining Moon of Secrets

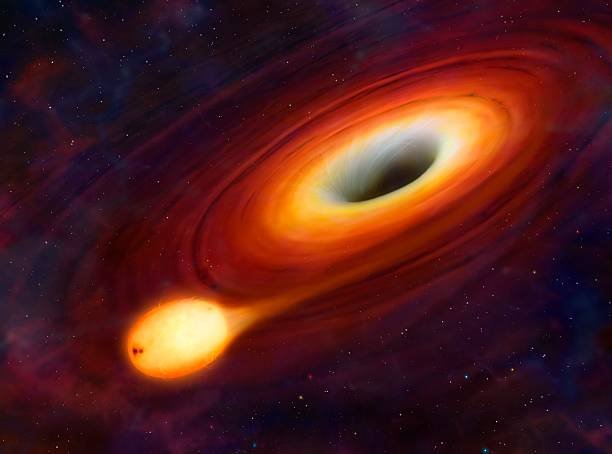

If Titan is Saturn’s most enigmatic moon, Enceladus is its most dazzling. Barely 500 kilometers across, this small, icy moon gleams with a brightness unmatched by any other object in the Solar System. Its surface reflects nearly all sunlight that strikes it—a clue to the fresh ice continually coating it.

In 2005, the Cassini spacecraft made a discovery that forever changed our understanding of where life might exist. Near Enceladus’s south pole, Cassini detected towering plumes of water vapor, ice particles, and organic molecules erupting from long fissures nicknamed “tiger stripes.” These geysers shoot material hundreds of kilometers into space, feeding Saturn’s faint E-ring and revealing the presence of a subsurface ocean beneath the crust.

The ocean beneath Enceladus’s icy shell is global, deep, and in contact with a rocky core. That contact is crucial—it means that hydrothermal vents, similar to those on Earth’s ocean floor, may exist there, releasing heat and minerals into the water. Cassini’s instruments found complex organic compounds in the plumes—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and even hints of molecular hydrogen, which serves as a potential energy source for microbial life.

In that discovery, Enceladus transformed from a frozen moon into one of the most promising locations for extraterrestrial life. Its geysers, like cosmic whispers, tell us that this small world is alive in a geological sense—and possibly in a biological one too. The search for life in Enceladus’s hidden ocean has become one of the defining quests of modern planetary science.

Mimas: The Death Star Moon

Of all Saturn’s moons, none has a more striking resemblance to science fiction than Mimas. With its enormous crater Herschel, spanning 130 kilometers across and nearly a third of the moon’s diameter, Mimas looks uncannily like the Death Star from Star Wars. Yet behind its cinematic appearance lies a world that continues to puzzle scientists.

Mimas is small and heavily cratered, suggesting an ancient and inactive surface. However, data from Cassini revealed an unexpected anomaly—its internal wobble implies that either Mimas has an elongated, icy core or possibly a subsurface ocean. If the latter is true, Mimas would join Enceladus and Titan as an ocean-bearing moon, an extraordinary finding given its small size and apparent lack of geological activity.

Mimas orbits just outside Saturn’s rings and plays a key role in shaping them. Its gravitational resonance helps maintain the structure of the Cassini Division, the dark gap separating Saturn’s A and B rings. In this way, Mimas acts as both sculptor and sentinel, subtly influencing the beauty that defines its parent planet.

Tethys: The Frozen Relic

Tethys, another of Saturn’s mid-sized moons, presents a world frozen in time. Its surface is bright, icy, and scarred by immense fractures and impact basins. The most striking feature is Ithaca Chasma, a canyon stretching over 2,000 kilometers—nearly three-quarters of the moon’s circumference. This colossal rift likely formed when Tethys’s interior froze and expanded, cracking the crust apart.

The giant crater Odysseus, with a diameter of 400 kilometers, dominates one hemisphere, giving the moon a battered appearance. Tethys’s density suggests it is composed mostly of water ice with only a small fraction of rock. With no atmosphere and little geological activity, it stands as a frozen monument to the early Solar System—a place where the story of impacts and formation remains etched into every ridge and crater.

Tethys also shares a fascinating orbital relationship with two tiny moons, Telesto and Calypso, which occupy its leading and trailing Lagrange points. These co-orbital companions illustrate the delicate gravitational balances that can exist in planetary systems, like beads following the same cosmic thread.

Dione: The Moon of Ghostly Cliffs

Dione is a world of contrasts. Its leading hemisphere is dark and cratered, while its trailing side gleams with bright streaks—long, icy cliffs called “wispy terrain.” These fractures are immense scarps where the crust has been pulled apart, possibly by tectonic forces or past subsurface activity.

Cassini’s observations revealed evidence of a tenuous atmosphere, composed mostly of oxygen ions generated by sunlight and charged particles striking the icy surface. More intriguingly, hints of subsurface activity suggest that Dione, like Enceladus, may harbor a buried ocean. Gravity measurements indicate that beneath its frozen crust lies a layer of liquid water, perhaps a relic of ancient heat still trapped within.

In many ways, Dione may represent an intermediate stage between a geologically dead world like Tethys and an active one like Enceladus. It is a moon that whispers of past vitality, now frozen into silence, yet still holding the memory of motion beneath its crust.

Rhea: The Ghost Moon

Rhea, the second-largest of Saturn’s moons, drifts through space like a pale ghost. Composed mostly of water ice and a small fraction of rock, it has a density barely higher than that of pure ice. Its surface is a record of impacts stretching back billions of years, suggesting that geological processes have long since ceased.

Cassini discovered that Rhea might have a tenuous ring system—the first such feature ever suggested around a moon—though later evidence remains inconclusive. More confirmed, however, is its extremely thin atmosphere of oxygen and carbon dioxide, produced by the interaction of sunlight and charged particles with surface ice.

Rhea’s simplicity belies its importance. As a largely unaltered body, it preserves the conditions of the early outer Solar System. Studying its composition and cratering provides insight into the bombardment history that shaped all icy worlds, from Europa to Pluto.

Iapetus: The Two-Faced Moon

Among Saturn’s moons, Iapetus stands apart for its haunting duality. One hemisphere is as dark as coal, while the other gleams with bright ice. This yin-yang world, discovered by Giovanni Cassini in 1671, has puzzled astronomers for centuries.

The dark material likely originates from the outer irregular moon Phoebe. Dust from Phoebe, spiraling inward, coats Iapetus’s leading side as it sweeps through space. Sunlight then warms the dark surface, causing ice to sublimate and redeposit on the colder, brighter hemisphere—a self-amplifying cycle that accentuates the contrast.

But Iapetus’s mysteries do not end there. A massive ridge runs along its equator, stretching 1,300 kilometers and rising up to 20 kilometers high. This equatorial wall gives Iapetus a walnut-like shape and may be the remains of an ancient ring system that collapsed onto the surface, or the frozen scars of early rotational bulging.

From its distant orbit, nearly 3.5 million kilometers from Saturn, Iapetus watches the planet like a quiet sentinel. Its dual nature—half dark, half light—embodies the beauty and strangeness that define Saturn’s realm.

The Shepherd Moons and the Rings

Saturn’s rings, shimmering bands of ice and rock, owe their order and grace to the influence of small moons known as “shepherds.” These moons—Prometheus, Pandora, Atlas, and others—orbit within or near the rings, using their gravity to confine and sculpt the ring edges.

Prometheus and Pandora, for instance, flank the narrow F ring, their repeated gravitational tugs shaping its braids and kinks. Atlas and Pan, both shaped like flying saucers due to ring material accreting at their equators, maintain gaps in the rings and provide clues to how moons and rings evolve together.

These interactions illustrate a cosmic dance of precision. The rings and moons exchange angular momentum, creating waves, wakes, and boundaries that ripple through the icy particles. What appears from Earth as serene and still is, in reality, a dynamic, living system—a symphony of gravity and motion.

Hyperion: The Chaotic Sponge

No moon in the Solar System behaves quite like Hyperion. Irregularly shaped and filled with deep craters, it resembles a floating sponge or pumice stone. Its porous structure makes it one of the least dense moons known, suggesting it is a loose collection of ice and rock barely held together by gravity.

Hyperion’s rotation is chaotic—it does not spin steadily but tumbles unpredictably as it orbits Saturn. This unique behavior arises from its irregular shape and the gravitational influence of Titan, which constantly perturbs its motion. To an observer on Hyperion, the Sun and Saturn would rise and set in random patterns, creating an utterly alien sense of time.

Cassini’s close flybys revealed that Hyperion’s surface is covered in dark, reddish material similar to that found on Iapetus, perhaps the product of organic molecules altered by radiation. Though lifeless and fragile, Hyperion stands as a reminder that even chaos can be beautiful in the vast order of the cosmos.

Phoebe and the Irregular Moons

Far beyond the main group of Saturn’s moons lies Phoebe, a dark, distant world thought to be a captured object from the Kuiper Belt. Its retrograde orbit—moving opposite to Saturn’s rotation—sets it apart from the regular moons, as do its heavily cratered surface and ancient composition.

Phoebe is a remnant of the early Solar System, a fossil from the time when icy planetesimals roamed freely. Its carbon-rich material and density suggest it formed in the outer reaches, far from the Sun, before being drawn into Saturn’s gravitational domain.

Phoebe also contributes dust that migrates inward, coating Iapetus’s leading hemisphere and creating its famous dark face. Thus, even from its remote orbit, Phoebe influences the appearance of its inner kin—a testament to the far-reaching interconnectedness of Saturn’s system.

A Laboratory for Planetary Science

The Saturnian system is a microcosm of planetary processes. Within its domain, scientists study everything from atmospheric dynamics to cryovolcanism, from magnetic interactions to orbital resonance. Each moon provides a case study in how environment, composition, and gravitational context shape celestial bodies.

Enceladus and Titan, with their subsurface oceans and complex chemistry, inform the search for life elsewhere. The shepherd moons reveal how gravity structures planetary rings and how new moons might form. Even the smallest fragments hold clues to the processes that sculpted the early Solar System.

The Cassini-Huygens mission, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, revolutionized our understanding of these worlds. It mapped surfaces, analyzed atmospheres, flew through plumes, and captured vistas of stunning beauty. Its data continue to yield discoveries, ensuring that Saturn’s moons remain vibrant subjects of study long after the spacecraft’s final plunge into the planet’s atmosphere.

The Potential for Life

Among all the moons of Saturn, two stand out as potential homes for life—Enceladus and Titan. Both possess liquid water, energy sources, and organic molecules, the essential ingredients for biology as we know it.

On Enceladus, hydrothermal vents at the ocean floor may provide the warmth and chemistry to sustain microbial ecosystems akin to those near Earth’s black smokers. On Titan, prebiotic chemistry driven by sunlight and cosmic rays could be producing complex organic molecules, perhaps leading to exotic life based not on water, but on methane and ethane.

Future missions, such as NASA’s Dragonfly drone to Titan and proposed sample-return missions to Enceladus, will seek to answer one of humanity’s most profound questions: Are we alone, or does life thrive in the cold shadows of Saturn’s moons?

The Eternal Allure of Saturn’s Realm

To stand on one of Saturn’s moons and gaze upward would be to witness a spectacle beyond imagination. The planet’s golden globe would dominate the sky, its rings arching overhead in broad, gleaming bands. Sunlight, dim and golden, would filter through the haze or reflect off the ice. In such a sky, beauty and silence would intertwine, and the human mind would confront both awe and humility.

The moons of Saturn are more than astronomical bodies—they are expressions of the universe’s creativity. Each one reveals a facet of cosmic artistry: the organic mists of Titan, the icy fountains of Enceladus, the fractured cliffs of Dione, the two-toned mask of Iapetus. Together they form not merely a collection, but a symphony—a planetary system rich with diversity and meaning.

Jewels in the Cosmic Crown

Saturn’s moons remind us that the universe is not uniform but abundant, not still but dynamic. They are the jewels in the planet’s crown, shimmering across the cold reaches of space, each one a story written in ice and stone.

Through them, we glimpse the forces that shaped not only Saturn but all planetary systems—the collisions, the chemistry, the tides, and the time that turn chaos into cosmos. They invite us to wonder, to explore, and to dream of other worlds where oceans lie beneath frozen shells, where skies rain methane, and where sunlight glows faintly on landscapes that have never known life.

And perhaps, one day, when human explorers set foot upon those distant shores—beneath the pale light of Saturn’s rings—they will look up and see the planet gleaming above them, encircled by its myriad moons. In that moment, they will know they stand not in isolation but within the vast and intricate beauty of creation itself—the cosmic crown of Saturn, glittering eternally in the dark.