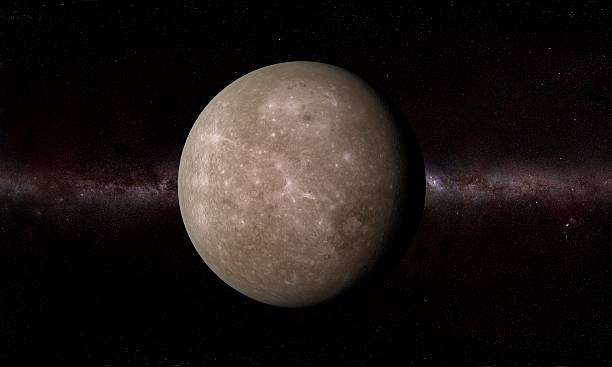

Mercury, the smallest and innermost planet in our solar system, lives in a realm of extremes. It orbits so close to the Sun that from its surface, the star blazes more than three times larger and seven times brighter than it appears from Earth. It is a world of blistering heat and freezing darkness, a planet of paradoxes—ancient, scarred, and yet still whispering secrets we have only just begun to hear.

Though it circles the Sun faster than any other planet, Mercury hides many mysteries beneath its silence. For centuries, it was an enigma glimpsed only briefly in the twilight skies—too close to the Sun to study easily, too small and secretive to yield its nature without effort. Even today, with spacecraft and telescopes peering closer than ever, Mercury defies expectations. It is not merely a scorched rock, as once imagined, but a complex and dynamic world, shaped by cosmic violence, magnetic power, and time itself.

The Elusive Wanderer

Mercury was known to ancient civilizations long before telescopes revealed the details of planets. The Sumerians, Babylonians, and Greeks all noticed a bright “wandering star” that appeared briefly at dawn or dusk, never straying far from the Sun. To the ancient Greeks, it seemed to be two different objects—Apollo, the morning star, and Hermes, the evening one—until they realized both were the same celestial body.

The Romans later named it Mercury, after their swift messenger god, for its rapid journey across the sky. The name fits perfectly. Mercury races around the Sun in just 88 Earth days, completing more than four orbits in a single Earth year. Yet despite its speed, it rotates slowly, taking 59 Earth days to spin once on its axis. This strange rhythm—called a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance—means Mercury experiences a day (sunrise to sunrise) lasting 176 Earth days.

For ancient astronomers, Mercury was mysterious because it was elusive; for modern scientists, it remains mysterious because it breaks so many of our expectations about how planets should behave.

A Surface Forged by Fire and Fury

At first glance, Mercury looks like the Moon—gray, cratered, and seemingly lifeless. But this resemblance hides a far more dramatic history. Mercury’s surface tells a tale of ancient violence and slow geological transformation.

Billions of years ago, during the chaotic youth of the solar system, Mercury was bombarded by asteroids and comets. These impacts carved out enormous craters and basins, some stretching hundreds of kilometers across. The most spectacular of these is the Caloris Basin, a colossal scar roughly 1,550 kilometers wide—one of the largest impact basins in the entire solar system. The force of the impact that created it was so immense that it sent shockwaves around the planet, raising chaotic hills and ridges on the opposite side.

But Mercury is not just a frozen graveyard of craters. After the great impacts, vast plains of lava welled up from its interior, flooding lowlands and burying ancient scars. These volcanic plains cover large portions of the planet, hinting at a time when Mercury was far more geologically active. Today, the volcanoes are silent, but their shapes—smooth, round vents surrounded by frozen lava—tell us that this small world once burned with inner fire.

The planet’s surface temperature swings are some of the most extreme in the solar system. During the day, the Sun’s fierce glare heats Mercury’s surface to about 430°C (800°F), hot enough to melt lead. But when night falls, the lack of an atmosphere allows the heat to vanish into space, plunging temperatures to –180°C (–290°F). This brutal contrast, a difference of over 600 degrees Celsius, makes Mercury both one of the hottest and coldest worlds in our cosmic neighborhood.

The Great Shrinking Planet

One of Mercury’s most fascinating mysteries is that it appears to be shrinking. Across its surface, enormous cliffs—called lobate scarps—cut through craters and plains, stretching for hundreds of kilometers and rising up to several kilometers high. These cliffs are signs that the planet’s interior has cooled and contracted over time, causing its crust to buckle and fold like a wrinkled orange.

This global contraction is unique. No other planet shows evidence of such widespread shrinking. Scientists estimate that Mercury’s diameter has decreased by about 14 kilometers (9 miles) since its formation. It is as though the planet has been slowly pulling itself inward for billions of years, its once-molten heart turning solid and drawing its skin tighter.

The discovery of these scarps, first revealed by spacecraft images, tells a story of a world still changing long after its birth. Mercury may seem inert, but its scars are fresh enough that contraction could still be occurring today—a reminder that even the smallest planet can still reshape itself in silence.

The Mystery of the Giant Core

Perhaps the most puzzling feature of Mercury lies deep within: its enormous metallic core. For such a small planet, Mercury has an astonishingly large and dense interior. Nearly 85% of its radius is taken up by an iron-rich core, leaving only a thin mantle and crust. This makes Mercury the densest planet in the solar system after Earth.

But why is its core so large? There are several competing theories. One suggests that Mercury once had a thicker mantle, which was blasted away by a massive collision early in its history. Another proposes that the intense heat and radiation from the young Sun vaporized much of Mercury’s lighter materials, leaving behind a dense metallic remnant. A third idea is that Mercury formed in a region of the solar nebula where only heavy, metal-rich materials could condense.

Whatever the cause, Mercury’s overgrown core is not just a curiosity—it’s a window into the solar system’s violent origins. It also holds another surprise: it is at least partially molten. This molten metal powers Mercury’s magnetic field, an unexpected feature for such a small and supposedly “dead” planet.

The Enigma of Mercury’s Magnetic Field

When NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft flew past Mercury in 1974, scientists were astonished to discover that the planet had a global magnetic field. Until then, they believed only large, geologically active planets like Earth could sustain one.

Mercury’s magnetic field is weak—about 1% the strength of Earth’s—but it is real and dynamic. It suggests that despite its size, Mercury’s core remains partly liquid and convecting, generating a magnetic dynamo. How this is possible, given the planet’s small size and age, remains a question that continues to puzzle scientists.

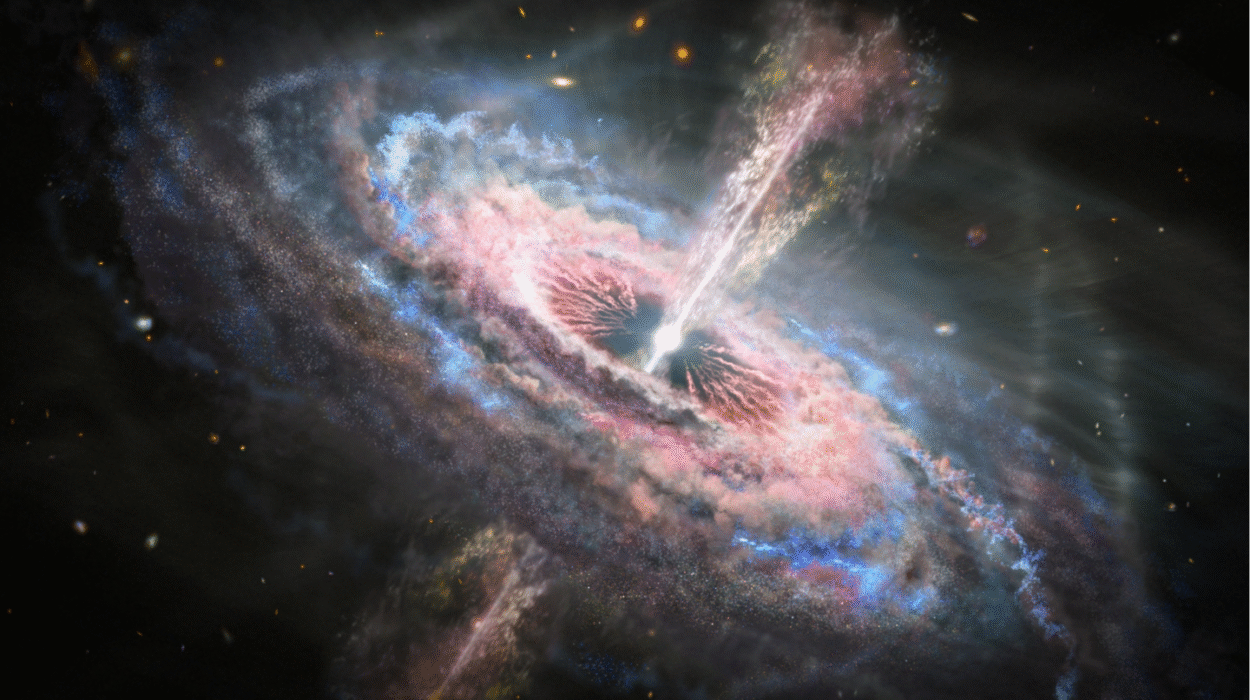

Moreover, Mercury’s magnetic field interacts with the solar wind—the stream of charged particles from the Sun—in fascinating ways. This interaction creates a miniature magnetosphere, similar in shape to Earth’s but far more volatile. Solar storms can compress it dramatically, causing bursts of energetic particles to rain down on Mercury’s surface.

This delicate balance between the planet’s weak field and the Sun’s ferocious power makes Mercury a living laboratory for understanding how magnetic fields evolve in extreme conditions.

A Thin Veil of Exosphere

Mercury has no true atmosphere—its gravity is too weak, and the Sun’s heat too intense, to hold one. Yet it does possess a tenuous “exosphere,” a thin veil of atoms that hover briefly above its surface before escaping into space. This exosphere is constantly replenished by several processes: solar radiation knocking atoms loose, micrometeorite impacts ejecting material, and gases released from the planet’s crust.

The main components of this ghostly exosphere are oxygen, sodium, hydrogen, helium, and potassium. Sodium, in particular, gives Mercury a faint yellowish glow when viewed in certain wavelengths of light. Though invisible to the naked eye, this exosphere is a fragile halo—part of a delicate dance between Mercury’s surface and the solar wind.

This dynamic, ever-changing envelope provides crucial clues about how the Sun shapes and strips the atmospheres of rocky planets. It also helps scientists understand how space weather interacts with airless worlds—a question relevant not just to Mercury, but to the Moon, asteroids, and even exoplanets orbiting close to other stars.

The Polar Ice Mystery

It may sound impossible that a planet scorched by the Sun could harbor ice—but Mercury does. Near its poles, inside deep craters where sunlight never reaches, radar observations have revealed bright, reflective patches consistent with frozen water.

These icy deposits likely come from ancient comet impacts or from water molecules carried by micrometeorites. Because Mercury’s rotational axis is nearly upright—tilted only about 0.03 degrees—its polar craters remain in perpetual shadow, forming natural freezers that trap ice for billions of years.

The discovery of ice on Mercury has profound implications. It shows that even in the most hostile environments, the universe preserves pockets of stability and possibility. It also raises intriguing questions about how water moves around airless bodies and whether similar cold traps might exist elsewhere, including on the Moon and other rocky planets.

The Dance of Heat and Shadow

Standing on Mercury would be a surreal experience. The sky would be black even at noon, for its thin exosphere cannot scatter sunlight into blue. The Sun would loom immense and dazzling, its light so intense that shadows would appear knife-sharp and almost solid.

If you stood at the equator at dawn, you would witness a sight unlike any other in the solar system. Because of Mercury’s strange rotation and orbit, the Sun would rise, pause, set again briefly, and then rise once more—performing a celestial dance in slow motion. The heat would climb until the ground beneath you could melt tin, then fall away into deadly cold as night returned.

This alternating inferno and frost gives Mercury a character unlike any other planet. It is a world ruled not by gentle seasons, but by relentless extremes—a world where time and temperature bend in strange ways, and where the Sun itself seems to play tricks on the horizon.

The Challenges of Exploration

Exploring Mercury is one of the greatest technical challenges in planetary science. Its proximity to the Sun makes it a difficult target. Spacecraft approaching Mercury must fight the Sun’s powerful gravity, requiring enormous amounts of energy to slow down and enter orbit. Additionally, the intense heat near the Sun poses serious risks to instruments and equipment.

The first spacecraft to visit Mercury was NASA’s Mariner 10, which flew by three times in 1974–75, capturing humanity’s first close-up images of the planet. For over three decades after that, Mercury remained largely unexplored, until NASA’s MESSENGER mission (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) arrived in 2011.

MESSENGER orbited Mercury for four years, mapping its entire surface and revealing stunning details about its geology, composition, and magnetism. It discovered volcanic vents, measured the planet’s exosphere, and confirmed the presence of polar ice. Its data transformed our understanding of Mercury from a simple rocky world into a dynamic, evolving planet.

Currently, the European-Japanese mission BepiColombo, launched in 2018, is on its way to Mercury. It is expected to arrive in 2026, carrying two orbiters that will study the planet’s magnetic field, surface chemistry, and interaction with the solar wind in even greater detail. BepiColombo’s mission represents the next great leap in unveiling Mercury’s enduring secrets.

Mercury and the Story of the Solar System

Mercury’s importance goes beyond its own mysteries. It is a time capsule from the earliest days of the solar system. Because it formed so close to the Sun, its composition and structure hold vital clues about how planets coalesced from the solar nebula.

By studying Mercury, scientists hope to answer fundamental questions: Why did the inner planets become rocky while the outer ones grew into gas giants? How did solar radiation influence planetary formation? What role did collisions play in shaping planetary interiors?

Mercury’s dense core and thin crust offer a window into these ancient processes. They may reveal how materials were distributed in the early solar system and how heat and magnetism affected planetary evolution. In this sense, Mercury is not just a planet—it is a living fossil, preserving the fingerprints of creation itself.

A Planet of Paradoxes

Everything about Mercury seems to defy expectation. It is small, yet dense. Barren, yet geologically complex. Close to the Sun, yet host to ice. It spins slowly but races around its orbit. It has no true atmosphere but boasts a magnetic field.

These contradictions are what make Mercury so fascinating. It is a reminder that nature rarely fits neatly into human categories. The closer we look, the more it reveals its subtleties and surprises. Mercury’s mysteries challenge our understanding of how worlds form, how they evolve, and how they endure in the face of cosmic violence.

Mercury and the Language of Light

When we observe Mercury through telescopes, we see more than a small gray disk—we see time itself etched into stone. Each crater, ridge, and basin tells a chapter of the solar system’s history. Every beam of sunlight that glances off its metallic plains carries information about the earliest dawn of planetary creation.

Spectroscopic studies show that Mercury’s surface is rich in refractory elements—materials that can withstand high temperatures. This confirms that it formed in the Sun’s furnace, where only the toughest elements could survive. Yet it also shows traces of volatile substances, suggesting that even here, close to the inferno, the universe preserved a hint of its cooler, more distant origins.

Light, both visible and invisible, is the key to decoding Mercury’s secrets. By analyzing reflected sunlight and emitted infrared radiation, scientists can determine the composition, texture, and temperature of its surface. Through radio signals bouncing off its crust, they can measure its internal structure. Even Mercury’s faint magnetic whispers reveal stories about its liquid core and the slow evolution of its heart.

The Human Connection

Though distant and inhospitable, Mercury has long fascinated humanity. In astrology and mythology, it symbolizes intellect, communication, and swiftness—qualities drawn from its fleeting presence in the dawn and dusk skies. In science, it stands as a monument to endurance, surviving close to the Sun’s destructive power for billions of years.

Every mission that reaches Mercury is a triumph of ingenuity and curiosity. To send machines into such an unforgiving environment—where sunlight can melt metal and gravity threatens to pull everything sunward—is an act of courage and imagination. It speaks to the unyielding human desire to know, to explore, and to find beauty even in the harshest places.

When we look at Mercury, we are reminded of ourselves: small, fragile, yet unafraid to journey toward the fire.

The Eternal Messenger

Mercury remains, in every sense, a messenger. It carries information from the birth of the solar system, encoded in its rocks and metals. It speaks of cataclysms and survival, of ancient heat and enduring cold. It tells us that even in the Sun’s shadow, mystery thrives.

As BepiColombo approaches and future missions prepare to follow, we stand on the edge of discovery once more. Each new image, each new measurement, brings us closer to understanding how worlds are born, how they live, and how they die.

But Mercury’s greatest lesson may be something simpler: that the universe’s smallest worlds can hold the deepest truths.

The Planet That Shouldn’t Be

In many ways, Mercury challenges the very models we use to explain the solar system. According to conventional theories, such a small planet so close to the Sun should have lost its volatiles long ago and cooled into inert stone. Yet Mercury defies this. It holds traces of sulfur and potassium, elements that should have boiled away. It maintains a magnetic field that should have faded eons ago. Its core is still partially molten, and its surface is still subtly shifting.

Mercury’s existence reminds us that the cosmos is not a predictable machine but a living, evolving entity. Each world is an experiment in physics and chemistry, a unique outcome of cosmic chance and necessity.

In studying Mercury, we confront the limits of our own understanding. The closer we get to the Sun, the more the universe burns away our assumptions, leaving only truth—bright, stark, and beautiful.

A Beacon in the Solar Dawn

As the first planet from the Sun, Mercury stands as a sentinel at the solar gateway. It witnesses the full fury of the star’s energy, enduring where few worlds could. It is both ancient and alive, both simple and mysterious.

From Earth, we see it for only moments—low in the twilight, shimmering like a jewel on the horizon. Yet in those fleeting glimpses lies a story billions of years long, written in craters and cliffs, metal and magnetism.

Mercury’s mysteries continue to challenge us, but they also inspire us. They remind us that even the smallest world can hold vast significance. In the brilliance of the Sun’s light, Mercury stands not as a shadow, but as a symbol of resilience—a world that has survived fire and silence, still turning, still reflecting the dawn.

The Endless Quest

The journey to understand Mercury mirrors our own journey as a species. We seek answers in the face of mystery, we reach for light even when it blinds us, and we find meaning in the most desolate places.

Mercury teaches us that knowledge is born not from comfort, but from curiosity. That beauty endures even where nothing can live. That the universe, in all its grandeur, reveals its secrets one by one to those who dare to listen.

In the end, the mysteries of Mercury are also the mysteries of ourselves—the drive to explore, the courage to question, and the endless wonder that makes us human.

For as long as the Sun burns and planets circle its fire, Mercury will continue its swift and silent dance—a messenger forever reminding us that even in the closest orbit to the Sun, mystery is eternal, and discovery is without end.