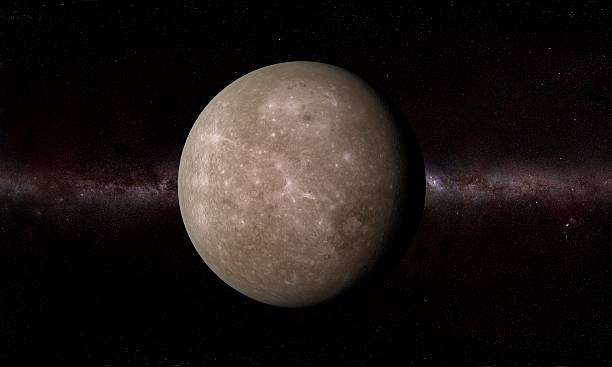

In the far reaches of our solar system, beyond the comforting warmth of the Sun and the familiar orbit of Saturn, lies a planet often shrouded in mystery—Uranus. It drifts through the cosmic night like a pale turquoise ghost, faint and distant, its secrets half-lost in the cold vacuum of space. While Jupiter and Saturn flaunt their majestic rings and well-known moons, Uranus remains quiet, almost secretive. Yet orbiting this frozen world is a family of moons unlike any other—enigmatic, haunting, and filled with strange beauty.

The moons of Uranus are not mere rocks in the void; they are worlds with stories written in ice and shadow. Each carries echoes of cosmic drama—of collisions, frozen oceans, and geologic scars that hint at a dynamic past. Some are named after Shakespearean spirits and heroines, others after poetic figures from Alexander Pope’s imagination. Together, they form a celestial theater circling a planet tipped on its side, performing an eternal play under the dim light of a distant Sun.

These moons—twenty-seven known so far—are among the least explored in the solar system. Yet their mysteries could help us understand not only Uranus itself but also the story of planetary systems across the cosmos.

A Tilted World and Its Eccentric Family

Uranus stands apart from every other planet in the solar system. Its axis of rotation is tilted at a staggering 98 degrees—essentially, it rolls through space on its side. This unique orientation gives the planet and its moons bizarre seasonal cycles: for decades at a time, one hemisphere bathes in unending sunlight while the other endures a long, frigid night.

This tilt likely resulted from a colossal collision early in Uranus’s history—an impact so violent that it could have reshaped the entire system. The same cataclysm that toppled Uranus may also have given birth to its moons or altered their orbits dramatically. Unlike the regular, equatorial moons of Jupiter or Saturn, Uranus’s satellites follow the planet’s tilted equator, revolving in harmony with its peculiar orientation.

This strange geometry makes the Uranian system feel almost alien. From the perspective of an observer on one of its moons, the Sun would rise and set in places that defy logic, tracing arcs across the sky that shift unpredictably over the course of Uranus’s long 84-year orbit around the Sun.

The Discovery of the Invisible Companions

When Uranus was first discovered by William Herschel in 1781, it became the first planet found with a telescope—a turning point in human astronomy. Just a few years later, in 1787, Herschel also discovered the first two Uranian moons: Titania and Oberon. They were faint, but unmistakably there, orbiting their distant parent like tiny sparks in the dark.

For nearly fifty years, these two were the only known moons of Uranus. Then, in 1851, astronomer William Lassell found two more—Ariel and Umbriel—doubling the planet’s known family. Much later, in 1948, Gerard Kuiper discovered Miranda, a smaller and closer moon with a fractured, patchwork surface.

For over a century, those five were all we knew. Then, in 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft swept past Uranus, becoming the first—and so far only—probe to visit the planet. What it revealed transformed our understanding. Voyager 2 discovered ten additional small moons, intricate rings, and a system more complex and alive than anyone had imagined.

Since then, advances in telescopes—especially the Hubble Space Telescope and large ground-based observatories—have revealed twelve more moons, bringing the total to twenty-seven. Each discovery has deepened the enigma, hinting at a system shaped by violence and mystery.

The Five Major Moons: Shakespeare’s Frozen Ensemble

Among Uranus’s twenty-seven moons, five stand out as the largest and most prominent—Titania, Oberon, Ariel, Umbriel, and Miranda. They are the pillars of the Uranian system, and their names, drawn from Shakespeare and Pope, evoke stories of beauty, mischief, and tragedy. Yet their real stories, written in rock and ice, are stranger still.

Titania: The Queen of the Ice Realm

Titania, the largest moon of Uranus, reigns as its icy queen. Measuring 1,578 kilometers in diameter, it is the eighth largest moon in the solar system—smaller than Earth’s Moon but larger than Pluto. Its surface gleams with frozen water mixed with dark organic compounds, and it is crisscrossed by massive fault valleys, some stretching hundreds of kilometers.

These vast canyons suggest that Titania once expanded as its interior froze, cracking its crust open. This implies that beneath its surface, there may once have been, or perhaps still is, a subsurface ocean. If so, Titania could harbor one of the outer solar system’s many hidden seas—a cold, dark ocean trapped beneath kilometers of ice.

Its landscape is ancient but not static. Craters overlap faults, indicating a complex history of impact and internal activity. Scientists believe Titania’s interior may still contain enough radioactive decay heat to maintain pockets of liquid water deep below—a tantalizing possibility for the presence of exotic forms of life.

Oberon: The Shadowed King

Farther out orbits Oberon, the second-largest moon of Uranus and the outermost of the major five. It is a world of darkness—its surface among the blackest in the solar system, absorbing nearly all sunlight that touches it. Craters blanket its face, hinting at an ancient, unchanging world battered by countless impacts over billions of years.

Yet Oberon is not entirely lifeless. Some of its largest craters have bright central peaks, where impacts may have exposed fresher ice from beneath. There are also hints of cryovolcanism—ice volcanoes that may once have erupted water mixed with ammonia or methane, freezing instantly in the frigid vacuum.

Oberon’s isolation and dark beauty make it a haunting world. It orbits nearly 600,000 kilometers from Uranus, where the planet’s pale blue disk would appear small but bright in its sky—a lonely sunlit ghost presiding over a frozen kingdom.

Ariel: The Bright and Restless Spirit

Closer to Uranus lies Ariel, perhaps the most fascinating of the major moons. It is the brightest and most geologically youthful of them all, its surface shaped by flowing ice, cliffs, and deep canyons. Ariel appears to have been active in the relatively recent past—at least by cosmic standards.

Voyager 2 revealed vast fault systems and smooth plains that suggest cryovolcanic resurfacing. Some valleys appear to have been carved by liquid flows—likely water mixed with other volatile compounds that erupted from beneath. Ariel’s youthful surface could indicate that internal heating, possibly from tidal forces caused by Uranus’s gravity, once kept its interior warm enough for geological activity.

Of all Uranus’s moons, Ariel is the one that most resembles a miniature Earth in terms of tectonic and erosional processes. Its bright, clean ice reflects sunlight efficiently, making it stand out against Uranus’s dim glow like a radiant silver spark.

Umbriel: The Dark and Silent Moon

If Ariel is light and renewal, Umbriel is shadow and stillness. Its surface is darker than any of the major moons, covered in ancient craters and mysterious dark material that absorbs sunlight. Umbriel seems to have been geologically dead for billions of years—a preserved relic of Uranus’s early history.

Yet it has one curious feature: a bright ring surrounding a crater named Wunda, a splash of light on an otherwise pitch-dark world. Scientists aren’t sure what caused it—it may be a deposit of frost or ice thrown up by an impact. This solitary bright mark gives Umbriel an eerie appearance, like an eye staring from the darkness of the outer solar system.

Miranda: The Broken World

Of all Uranus’s moons, none is as strange as Miranda. It is small—only about 470 kilometers across—but it is one of the most bizarrely scarred bodies in the solar system. Voyager 2’s images revealed vast cliffs, canyons, and patchwork terrains that look almost artificial.

Miranda’s surface appears to have been shattered and reassembled multiple times. Some regions rise 20 kilometers above others—enormous cliffs dwarfing anything on Earth. The most famous of these, Verona Rupes, may be the tallest known cliff in the solar system, plunging more than 10 kilometers into shadow.

What caused such devastation? Some scientists believe Miranda was torn apart by impacts or tidal forces and later reassembled by gravity. Others think internal heating caused partial melting and refreezing, warping its crust into the strange jigsaw we see today.

Miranda’s grotesque beauty makes it one of the most compelling worlds in the solar system—a place where geology tells a story of destruction, rebirth, and survival against impossible odds.

The Lesser Moons: A Chorus of Shadows

Beyond the major five, Uranus hosts a collection of smaller moons that form a rich and varied ensemble. Some hug close to the planet, orbiting within or near its faint ring system; others roam farther out, tracing wide, irregular paths through the planet’s gravitational field.

Many of the inner moons—such as Cordelia, Ophelia, Portia, Juliet, Rosalind, Belinda, and Puck—are irregularly shaped, battered by impacts, and likely fragments of larger bodies that broke apart long ago. They are locked in delicate gravitational resonances that help maintain Uranus’s ring structure, shepherding particles and keeping the thin rings stable.

Puck, the largest of these inner moons, is about 160 kilometers wide and riddled with craters. Its gray, dark surface suggests a composition of water ice mixed with carbon-rich material. Puck’s orbit sits just outside Uranus’s main ring system, making it a bridge between the inner and outer moons.

Farther out, the irregular moons tell another story. These outer satellites—like Sycorax, Caliban, Prospero, and Setebos—follow eccentric, inclined, and often retrograde orbits, meaning they move in the opposite direction of Uranus’s rotation. These odd trajectories suggest that they were not born alongside Uranus but were captured long ago from the surrounding region of the solar nebula.

Each of these moons may once have been an independent object wandering through space until Uranus’s gravity pulled it into orbit, trapping it in an eternal dance around the tilted planet.

A System Born of Chaos

How did this peculiar family come to be? The leading theory is that Uranus suffered a massive collision early in its history—a blow so immense it knocked the planet onto its side and reshaped its surroundings. Such an event would have vaporized or ejected any original moons, leaving debris that later coalesced into the ones we see today.

This scenario explains the uniform tilt of Uranus’s moons and rings—they all orbit in the plane of Uranus’s equator, which itself is tilted nearly perpendicular to the Sun. It also accounts for the relatively low mass of the moon system compared to those of Jupiter and Saturn; much of the original material may have been lost during the collision.

If this theory is true, then every moon of Uranus is a child of catastrophe—born from destruction, sculpted by gravity, and frozen in silence. They are relics of an ancient upheaval, still circling the planet that once turned over in the cosmic dark.

The Enigma of Subsurface Oceans

Recent studies have revived an intriguing idea: that several of Uranus’s moons might harbor subsurface oceans beneath their icy crusts. Data from Voyager 2, combined with new modeling, suggest that Titania, Oberon, Ariel, and possibly Umbriel could have layers of liquid water trapped beneath kilometers of ice.

Though the Sun’s heat is weak at Uranus’s distance, internal heating from radioactive decay or past tidal flexing could keep these oceans from freezing entirely. If true, these hidden seas might be chemically rich, containing ammonia and salts that lower the freezing point of water.

Such environments could be potential habitats for microbial life, similar to what scientists suspect may exist on Europa or Enceladus. The possibility that even distant, frozen moons could conceal living oceans beneath their surfaces deepens the mystery of the Uranian system.

Voyager 2: A Fleeting Visit to the Unknown

In January 1986, Voyager 2 became humanity’s lone emissary to Uranus. It flew within 81,500 kilometers of the planet, capturing the first close-up images of its moons. For just a few days, the veil of mystery lifted.

The spacecraft revealed a planet of serene blue-green beauty and moons that defied expectation. It showed Miranda’s shattered face, Ariel’s bright canyons, and Titania’s deep faults. But the encounter was brief—too brief. After its flyby, Voyager 2 continued on toward Neptune, leaving Uranus and its moons in darkness once again.

Those few days of data remain our only detailed glimpse of the Uranian system. In the decades since, no spacecraft has returned. The images and measurements from Voyager 2 still serve as our window into these faraway worlds—snapshots frozen in time.

The Case for Return

Today, planetary scientists are calling for a new mission to Uranus. With modern technology, we could finally study its atmosphere, magnetic field, and moons in unprecedented detail. The 2023 U.S. National Academies’ Decadal Survey identified a Uranus orbiter and probe as the top priority for the next large planetary mission.

Such a mission could carry radar and infrared instruments to peer through the darkness, mapping the moons, probing their compositions, and searching for signs of geological activity or hidden oceans. It could deploy a descent probe into Uranus’s atmosphere, exploring its winds, chemistry, and energy balance.

For the moons, high-resolution imaging and gravity measurements could answer long-standing questions: Are they active? Do they contain liquid water beneath their surfaces? And what can they tell us about how ice-rich worlds evolve in the outer solar system?

A return to Uranus would not just fill a gap in exploration—it would open an entirely new frontier in planetary science.

The Poetic Names and Their Meaning

The moons of Uranus are unique not only in their nature but also in their names. Unlike the mythological naming tradition for most planetary satellites, Uranus’s moons are named after characters from the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope.

This tradition began with Herschel’s son, John Herschel, who proposed the names Titania and Oberon (from A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and continued with later discoveries: Ariel and Umbriel (from Pope’s The Rape of the Lock and Shakespeare’s The Tempest), and Miranda (from The Tempest).

The smaller moons continue this literary lineage—Ophelia, Cordelia, Puck, Rosalind, Desdemona, Juliet, and others—each carrying echoes of human imagination into the depths of space. It is as if Uranus’s tilted kingdom is populated by ethereal spirits from our greatest stories, circling forever in the twilight of a distant sun.

These names give the Uranian system a strange poetic resonance. The moons seem like dreamlike characters in a cosmic play—frozen actors upon an interstellar stage, each with a tale of beauty, chaos, or sorrow written in ice.

The Silent Ballet of Shadows

Seen from afar, the Uranian system would appear as a delicate ballet of shadows. The planet’s turquoise glow casts a soft light on its satellites, which orbit along the tilted plane like dancers tracing ghostly ellipses. The faint rings add a halo of glittering dust, each particle reflecting a glint of the Sun’s pale light.

From the surface of Titania or Oberon, Uranus would dominate the sky—a massive, glowing sphere stretching dozens of degrees across the heavens. Its rings would appear as luminous arcs, and its other moons would drift like small lanterns against the eternal blackness.

In that alien night, the Sun would be no brighter than a pinpoint star, its warmth almost gone. The light that reaches these moons is faint, but it reveals their subtle beauty: ice plains gleaming faintly blue, cliffs casting shadows hundreds of kilometers long, and crater rims shining like ancient scars.

It is a landscape both silent and sacred—a frozen dream suspended at the edge of sunlight.

The Moons as Messengers

Though we have yet to return to Uranus, its moons already speak to us. They tell of a universe where even the most distant and forgotten places hold wonders. They remind us that life and beauty can emerge from chaos, and that even in the darkest corners of space, stories endure.

The Uranian moons are more than cold rocks—they are archives of cosmic history. Each carries clues about the formation of the outer planets, the migration of celestial bodies, and the forces that shape worlds both near and far.

By studying them, we learn not only about Uranus but also about the mechanisms that build—and sometimes destroy—planetary systems across the galaxy.

The Future of Discovery

The next generation of explorers may one day witness the Uranian moons up close. Future missions could orbit them, land upon their surfaces, or send probes to dive into their icy crusts. We might map their canyons in fine detail, study their internal oceans, and perhaps even detect chemical traces of life beneath the ice.

With each new discovery, the story of Uranus will unfold—not as a cold and forgotten world, but as a dynamic system of beauty and complexity. Its moons, once distant points of light, may become key chapters in the greater epic of our solar system.

A Realm of Ice, Shadow, and Wonder

The mysterious moons of Uranus are like whispers from another era—remnants of a time when our solar system was still forming, when chaos and creation danced side by side. They orbit a world that defies convention, a planet that turns its face to the Sun in a way no other does.

Titania’s canyons, Oberon’s shadows, Ariel’s bright plains, Umbriel’s darkness, and Miranda’s shattered cliffs—all are chapters in a story of ice and fire, silence and survival. Around Uranus, the night is eternal, yet the light of discovery still shines.

When we finally return to this distant kingdom, we may find not just the remnants of the past, but the keys to the future—lessons about resilience, transformation, and the enduring beauty of worlds that seem forgotten.

For even in the farthest reaches of the solar system, among the moons of Uranus, the universe still dreams—and waits for us to listen.