The glory of ancient Rome has long captivated the imagination of historians, archaeologists, and lovers of the past. But behind that glory lies an older, far more mysterious civilization—one that built the foundation upon which Rome was raised. These were the Etruscans, a people whose language, customs, and rise to power remain shrouded in mystery, despite their profound influence on the ancient world.

When we think of Italy before Rome, the mind often draws a blank. Yet centuries before Romulus and Remus were said to have suckled at the wolf’s teat, Etruscan city-states flourished across the central Italian landscape, their wealth glimmering in gold, their art alive with vivid emotion, and their religious rites steeped in mysticism. Who were these enigmatic people? Where did they come from? And why, after centuries of dominance, did they vanish so completely into the folds of Roman history?

To explore the Etruscans is to venture into a world half-remembered, a lost civilization that left behind elaborate tombs, cryptic inscriptions, and a cultural legacy woven into the fabric of Roman identity. This is the story of the Etruscans—Rome’s mysterious predecessors.

The Land of Etruria

Long before Italy was unified under Roman banners, the land of Etruria stretched across a swath of central Italy, encompassing parts of what we now call Tuscany, Lazio, and Umbria. It was a fertile region dotted with hills, rivers, and natural resources that gave rise to thriving cities and prosperous trade networks.

By the 8th century BCE, Etruscan city-states were already well-established, forming a loose confederation of powerful urban centers. Among these were names that would later become familiar through Roman eyes: Tarquinia, Veii, Clusium, Vulci, and Cerveteri. These cities operated independently but shared a common language, religious practices, and artistic traditions.

The Etruscans excelled in engineering and urban planning. Their cities were laid out with organized streets and built with stone structures far ahead of their time. Even their drainage and sanitation systems foreshadowed the advanced infrastructure that Rome would one day perfect.

Yet despite their accomplishments, the Etruscans have left us little in the way of self-description. Most of what we know comes not from their own words but from the Romans and Greeks, whose accounts often mingled admiration with hostility.

The Question of Origins

Perhaps the greatest mystery surrounding the Etruscans is their origin. Ancient historians debated this question fiercely. Herodotus claimed they were immigrants from Lydia in Asia Minor, driven by famine to sail west and settle in Italy. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian living in Rome, disputed this, arguing they were indigenous to the Italian peninsula.

Modern archaeology and linguistics have added layers to the debate rather than settled it. The Etruscan language is unlike any other Indo-European tongue. It shares no clear relation to Latin, Greek, or even the older Italic languages. It seems to have no linguistic cousins at all—only scattered similarities with a few pre-Indo-European languages spoken in the distant past.

Genetic studies of ancient Etruscan remains reveal a population similar to other prehistoric Italians, suggesting a long-standing local origin. Yet cultural similarities to eastern Mediterranean civilizations remain tantalizing.

The most likely truth? The Etruscans may have emerged from a fusion of indigenous peoples and seafaring migrants, shaped by trade and contact with civilizations like the Greeks and Phoenicians. Whatever their origin, they became distinctly Etruscan—mysterious, innovative, and uniquely themselves.

A Civilization of Splendor

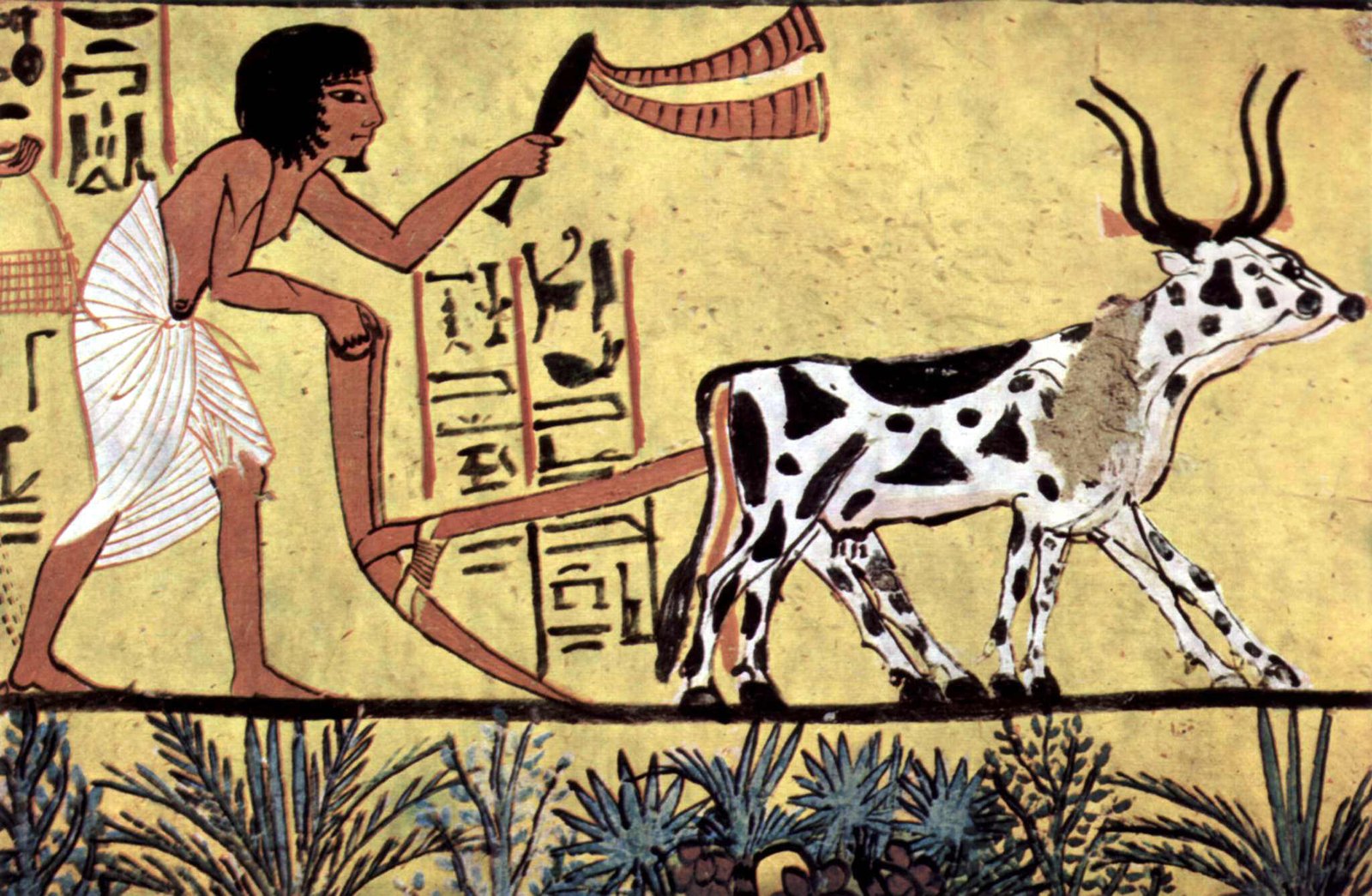

If Rome was a lion, aggressive and expansionist, Etruria was a peacock—ornate, refined, and expressive. The Etruscans delighted in art, luxury, and ceremony. Their tombs, carved into hillsides or built as above-ground mounds, are filled with frescoes that depict banquets, music, dancing, and scenes of the afterlife.

These tombs serve as time capsules. In places like Tarquinia and Cerveteri, we find vast necropolises that mirror the cities of the living. Inside are vivid murals painted in colors that have somehow survived the centuries—scenes that show Etruscans reclining on couches, clinking wine cups, and playing lyres. There’s a striking sense of joy in these depictions, a zest for life and an awareness of death.

The Etruscans were also master metalworkers. Their gold jewelry is so delicate and intricate that modern techniques struggle to replicate it. They worked in bronze and iron, forged armor and weapons, crafted statues, and created elaborate ceremonial objects.

And then there were the mirrors—polished bronze discs engraved with mythological scenes, often of Greek origin but interpreted through Etruscan eyes. These mirrors were more than tools for vanity; they were portals into a cosmology shaped by mystery and introspection.

A Language Lost

Few aspects of Etruscan culture frustrate scholars more than their language. It remains only partially deciphered. While we can read the letters—they used a script adapted from the Greek alphabet—the meanings of many words elude us.

Inscriptions appear on tombs, urns, amulets, and ceremonial items. But without a Rosetta Stone equivalent, the language remains an enigma. The longest known Etruscan text, the “Liber Linteus,” was found in an unexpected place: Egypt. Strips of linen bearing Etruscan writing had been used to wrap a mummy, preserved by accident.

Despite centuries of study, the Etruscan vocabulary remains largely a puzzle. We can identify names, titles, and religious phrases, but not much else. It is as if their voice echoes through time—but only in fragments.

Gods, Omens, and Sacred Rites

The Etruscans lived in a world saturated with signs and symbols. They believed the gods communicated through natural phenomena—lightning, bird flight, the entrails of sacrificed animals—and developed a complex system of divination to interpret the divine will.

Priests known as haruspices examined the livers of animals to discern omens. Bronze models of livers, like the famous “Liver of Piacenza,” show the names of gods and designated sectors used in these rites. Augurs read the skies and the behavior of birds to guide decisions in war and politics.

Their pantheon resembled those of the Greeks and Romans, but with unique local flavors. Tinia was the sky god, akin to Zeus or Jupiter. Uni, his consort, paralleled Hera or Juno. Menrva, the goddess of wisdom and war, prefigured the Roman Minerva.

Yet Etruscan religion was darker, more fatalistic. The afterlife was a shadowy realm, neither purely blissful nor entirely terrifying. Spirits of the dead—winged demons, benevolent guardians—were frequent subjects of tomb art, suggesting a belief in continued existence beyond death, if not eternal happiness.

A Political Mosaic

Unlike Rome, which built a centralized empire, Etruria was a patchwork of city-states. Each was politically independent, governed by kings or elected magistrates. While they shared language and religion, unity was rare and fleeting.

This lack of central authority was both a strength and a weakness. It allowed cities like Tarquinia and Veii to develop independently, nurturing artistic and economic rivalries. But it also made Etruria vulnerable to external threats—first from Greek colonists in the south, later from Rome.

Nevertheless, Etruscans played a major role in early Roman history. Several Roman kings, including the infamous Tarquin the Proud, were Etruscan. Rome’s early architecture, religion, and public rituals bear the clear imprint of Etruscan influence.

Conflict and Conquest

By the 5th century BCE, the tide began to turn. Greek colonies in southern Italy pushed north, challenging Etruscan naval dominance. Celtic tribes invaded from the north. But the greatest threat came from within Italy—from Rome.

Rome’s rise was meteoric. Once an obscure Latin settlement, it absorbed Etruscan customs and then turned against its mentors. The conquest of Veii in 396 BCE was a pivotal moment—Rome’s first major military victory and a devastating blow to Etruscan power.

Over the next century, Etruscan city-states fell one by one. Some tried to ally with Rome; others resisted fiercely. None succeeded. By the 1st century BCE, Etruria had been fully absorbed into the Roman Republic. The Etruscans, once masters of Italy, were now Roman citizens.

Legacy in Stone and Spirit

Though their independence faded, the Etruscans left a lasting legacy. Roman engineering, religion, political symbolism, and even social customs bore their mark. The Roman toga, the fasces (a bundle of rods symbolizing authority), and the triumphal procession all have Etruscan roots.

Rome inherited not just physical tools but a worldview. The Etruscan obsession with omens and the divine order influenced Roman state religion and political rituals. Etruscan artists, engineers, and seers continued to serve the Roman elite.

Even centuries later, emperors sought out Etruscan haruspices to interpret dreams and signs. Augustus himself took pride in restoring Etruscan temples, recognizing the foundational role they had played.

Rediscovery and Revival

For centuries, the Etruscans faded from memory. Their language unreadable, their cities buried, their identity consumed by the Roman colossus. But in the Renaissance, antiquarians and artists began unearthing Etruscan tombs and treasures. What they found reignited curiosity.

By the 19th and 20th centuries, systematic archaeology transformed our understanding of Etruria. Sites like Tarquinia, Cerveteri, and Volterra revealed a lost world of sophistication and depth.

And yet, the Etruscans remain elusive. Their language defies translation. Their myths are only partially known. Their story is fragmented—a mosaic with missing pieces. But this very mystery is what makes them so compelling. They challenge us to look beyond the grand narrative of Rome and see the shadowed grandeur of what came before.

Conclusion: Echoes from the Underworld

The Etruscans are gone, yet they whisper still. In the arches of Roman aqueducts, in the pages of Latin texts, in the rituals of ancient religion—they persist, not as conquerors, but as visionaries.

They remind us that history is not a straight line. It is a tapestry woven from many cultures, many voices, some louder than others. The Etruscans, though nearly silent, left their pattern woven deeply into the fabric of civilization.

Their story is one of brilliance and erasure, of cultural triumph and historical disappearance. But it is not a tragedy. For in the frescoes of their tombs, in the gold of their necklaces, and in the mysteries they left behind, the Etruscans endure—not as ghosts, but as ancestors of an idea: that even forgotten peoples shape the future.