In the heart of ancient Greek mythology, where gods walked among mortals and divine wrath shaped the fates of humankind, there exists a story unlike any other—a story that pierces the soul with its beauty and tragedy. It is the tale of Niobe, a queen whose pride led to unspeakable loss, whose grief became eternal, and whose tears turned into stone.

The myth of Niobe is more than just an ancient legend; it is a mirror reflecting the eternal human struggle between arrogance and humility, joy and despair, life and loss. Her name has become synonymous with mourning itself, and her tale has resonated through centuries as a poetic warning against the dangers of hubris—the fatal overconfidence that offends both gods and destiny.

But Niobe’s story is not simply about punishment. It is about love so fierce it defies even death. It is about a mother’s unbearable grief transformed into immortal sorrow. It is about the fragile boundary between human pride and divine order—a boundary that, once crossed, leaves only silence and stone.

The Queen of Thebes

Long before her tears became legend, Niobe was a queen of power and grace. She ruled the city of Thebes alongside her husband, King Amphion, one of the sons of Zeus and a man gifted with music so divine that stones themselves moved to form the walls of the city. Together, they were a royal pair unmatched in beauty and influence.

Niobe was not born to obscurity. She was the daughter of Tantalus, the king of Lydia, who himself was the son of Zeus. Thus, she shared divine blood—a lineage that pulsed with both pride and peril. From her earliest years, Niobe carried herself as one destined for greatness. Her beauty was said to rival that of the goddesses themselves, and her confidence radiated like sunlight on marble.

Thebes thrived under her reign. The people adored her, the courtiers praised her wisdom, and artists sang of her splendor. She bore many children—some say six, others say twelve. The exact number varies with each retelling, but what remains constant is that her children were the jewels of her heart. They were the living proof of her power, her vitality, and her divine favor.

Niobe’s love for her children was immense, but so too was her pride. In their faces, she saw not only beauty but a reflection of herself. Her motherhood became her crown, her children her living trophies. And in that pride, the first shadow of her tragedy began to fall.

The Festival of the Goddess

One fateful day, Thebes prepared to honor the goddess Leto—the mother of the twin deities Apollo and Artemis. A grand festival was declared. The city gathered to offer sacrifices and prayers to the goddess, whose motherhood symbolized devotion and divine virtue.

But Niobe watched the proceedings with growing resentment. Why, she wondered, should her people worship a goddess who had only two children when she herself had so many? Why should mortals kneel to a deity whose motherhood paled beside her own?

As the citizens of Thebes brought offerings to Leto’s temple, Niobe could no longer contain her scorn. She rose in the midst of the festival, her voice sharp with pride, and addressed the people.

“Why honor a goddess you cannot even see,” she declared, “when a living queen stands before you—a mother far more blessed? I, Niobe, have given birth to many children. My beauty surpasses Leto’s; my lineage is royal and divine. Shall I bow before her? No. I am greater. Let the people of Thebes honor me, not her.”

Her words rippled through the crowd like a storm wind. Some gasped, some fell silent, and others trembled at her audacity. To insult a goddess was no small matter in the ancient world. The gods were not forgiving, and Leto, though gentle, was the mother of the most formidable twins in Olympus—Apollo, god of the Sun, and Artemis, goddess of the Moon.

Niobe, blinded by pride, had set herself against the heavens.

The Wrath of Leto

When word of Niobe’s blasphemy reached Mount Olympus, Leto’s heart was pierced with indignation. She had endured humiliation before—wandering the earth to find a place to give birth to her divine children—but never had a mortal dared to mock her motherhood.

With quiet sorrow that soon turned to divine rage, Leto summoned her children. “Apollo, my son of light, and Artemis, my daughter of the hunt,” she said, “shall we allow this mortal queen to boast at my expense? Shall the pride of flesh defy the gods?”

The twins, radiant and merciless, nodded. To insult their mother was to invite divine retribution.

Descending from Olympus in a blaze of golden and silver light, Apollo and Artemis reached Thebes as silent avengers. The city lay unaware of the fate about to unfold. Niobe’s children played and laughed in the palace courtyards, the sun glinting on their hair—the same sun that would soon witness their end.

The Slaughter of Innocence

Apollo drew his bow, and the air quivered with divine wrath. One by one, his arrows found their marks among Niobe’s sons. The boys, full of life and laughter moments before, fell like blossoms cut by an invisible hand. Artemis followed, her arrows swift and silent, striking Niobe’s daughters as they cried out in terror.

The palace became a place of wailing and despair. Servants fled in panic; the city trembled under the weight of divine fury.

Niobe rushed through the chaos, screaming for her children, her cries echoing like thunder. One after another, she saw them fall—her pride transformed into unbearable loss. Some versions of the tale say one or two were spared; others say all perished. But in every telling, Niobe’s world shattered in that moment.

Her arrogance had summoned a storm she could not escape.

She stood among the bodies of her children, drenched in grief, her heart hollowed by her own folly. The gods had shown her the price of hubris—not through her own death, but through the destruction of everything she loved.

The Mother’s Lament

When the slaughter ended, the world grew still. The once-proud queen of Thebes was now a mother surrounded by lifeless forms. Her tears fell endlessly, soaking the earth beneath her feet. Her voice rose in wails that reached the heavens themselves—a sound of such sorrow that even the gods turned away.

“Cruel gods,” she cried, “take my life too! Why should I live when my children are gone? You have punished me beyond measure—turn me to stone if you must, but do not leave me to weep forever!”

Her words, heavy with anguish, carried a strange power. Whether out of pity or as a final act of punishment, the gods answered her plea. Her body grew cold and heavy. Her heartbeat slowed. Her skin hardened like marble.

Before long, Niobe was no longer flesh and blood. She became a statue—frozen in eternal mourning, her head bowed, her eyes forever weeping.

Yet even in stone, her grief did not end. From her petrified eyes, water flowed unceasingly. Her tears, they say, formed a small stream that ran down the slopes of Mount Sipylus, in her native land of Lydia.

To this day, travelers speak of a rock formation resembling a woman’s face, streaked with the traces of flowing water. They call it the Weeping Rock of Niobe.

The Symbol of Hubris

The Greeks, who saw divinity and moral lesson in every myth, regarded Niobe’s story as a profound warning. Her tragedy was not merely personal—it was cosmic, illustrating the sacred balance between mortals and gods.

Hubris, the sin of excessive pride, was one of the gravest offenses in Greek thought. It was the belief that a human could rival the divine, that one could stand above fate itself. Those who committed hubris invited nemesis—the inevitable punishment that restored order to the universe.

Niobe’s downfall thus became a timeless symbol of this principle. Her beauty, her power, her children—all the gifts that should have inspired gratitude—became the very instruments of her ruin.

Through her, the Greeks learned that even the greatest mortal must bow to humility. Pride blinds; reverence restores sight. Niobe’s transformation into stone was both punishment and redemption—a reminder that even in tragedy, there is a kind of immortality.

A Mother’s Grief Beyond Time

Yet to reduce Niobe’s story to a mere moral fable is to miss its deepest resonance. Beneath the lesson of hubris lies the raw, human agony of loss. Her story endures not because she defied the gods, but because she loved her children with a passion that transcends myth.

Her transformation into stone is not just divine retribution—it is the embodiment of grief itself. When words fail, when sorrow consumes the soul, one becomes motionless, hollow, numb. Niobe’s petrification is a poetic metaphor for that state of absolute despair.

The ancients believed her tears still flowed because true sorrow never ends—it merely changes form. Even when turned to stone, the heart can still remember, still ache, still weep.

Artists, poets, and sculptors across the centuries have been drawn to Niobe’s image. In her, they see not arrogance but the unbearable cost of love and loss. Her face has appeared in marble statues, in Renaissance paintings, in symphonies and poems—each capturing a different shade of her eternal mourning.

She is not simply a warning; she is an emblem of compassion, of the human capacity to feel so deeply that even death cannot silence it.

The Landscape of Memory

In western Turkey, near Mount Sipylus, a strange rock formation gazes over the valley. Locals call it the Niobe Rock. To some, it looks like a woman’s face turned toward the heavens, her eyes streaked by the flow of spring water. Scientists will tell you it is a natural formation, sculpted by wind and erosion over millennia.

But those who stand before it in the fading light of sunset often feel something different—a stillness, a sadness, a haunting sense of presence. The myth lives on in that silence. The mountain itself seems to remember.

For the ancient Greeks, landscape and myth were inseparable. Mountains were not mere stones; they were monuments of memory, sacred echoes of divine stories. The Weeping Rock of Niobe thus became more than a geological curiosity—it was a shrine to eternal emotion, a bridge between myth and the physical world.

Generations of travelers, poets, and pilgrims came to the site. Some offered flowers; others simply listened to the trickle of water and imagined it as the endless tears of a queen who once defied heaven.

Niobe in Art and Literature

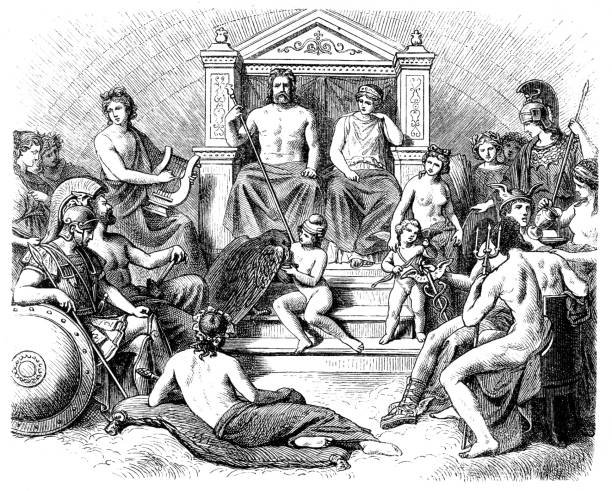

Niobe’s story captivated the imaginations of countless artists throughout history. In classical sculpture, she was depicted at the moment of her greatest despair—arms outstretched, eyes filled with terror, her children falling around her. The famous “Niobids” sculpture group, discovered in Rome and now housed in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, immortalizes that tragic instant. Each figure, carved from marble, captures the agony of divine punishment and human helplessness.

Poets too found in Niobe a muse of sorrow. Homer mentions her briefly in The Iliad, describing how even after death, she continued to weep for her children. Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, gave the most famous and haunting version of her tale—his verses dripping with empathy and awe.

In the Renaissance, Niobe became a symbol of maternal love and human vulnerability. Painters such as Richard Wilson and Jacques-Louis David depicted her as both sinner and saint—a figure who reminds humanity of its limits yet evokes infinite compassion.

Even in modern times, Niobe’s name echoes in literature, psychology, and philosophy. She is often invoked as a symbol of frozen grief, of the emotional paralysis that follows unbearable trauma. Her story transcends mythology—it enters the realm of universal human truth.

Between the Gods and the Human Heart

What makes Niobe’s myth so enduring is its dual nature—it exists both as divine allegory and human tragedy. On one level, it warns against pride; on another, it explores the deepest corners of emotion.

In Niobe’s pride, we see the human desire to be recognized, to be seen as worthy, even divine. She loved her children fiercely, but her love became a mirror for her ego. That tension between love and vanity, between gratitude and entitlement, is something timelessly human.

Her punishment, though cruel, reflects the ancient Greek vision of balance. The universe could not allow mortal arrogance to rival the gods. Yet even the gods showed mercy in the end—turning her not to ash, but to stone, and allowing her tears to flow forever.

In that act, the myth becomes almost compassionate. Niobe, the sinner, becomes sacred through suffering. Her grief transforms into something eternal, something that transcends her folly. She becomes not just a symbol of pride’s downfall, but of the endurance of the human heart.

The Eternal Weeping of the World

Niobe’s tears are not just her own. They are the tears of every mother who has lost a child, of every human who has watched love slip away. They are the world’s tears, crystallized into myth so that we might remember them.

In every age, humanity returns to Niobe when confronted with loss too great to bear. Her story offers no easy comfort—only the dignity of shared sorrow. She reminds us that grief, though unbearable, is also sacred; that love, though it can destroy, is also the most beautiful force we possess.

Her transformation into stone is not the end, but a kind of immortality. In her stillness, she becomes a monument to what it means to be human—to feel deeply, to err, to lose, to remember.

The mountain still weeps. The water still flows. The myth lives on because grief never truly ends—it only changes form.

The Legacy of Niobe

Thousands of years after the myth first echoed through Greek temples and marketplaces, Niobe remains alive in the collective imagination. Her name appears in poetry, art, psychology, and even astronomy. She is the eternal mourner, the symbol of love turned to loss, of pride turned to penitence.

Every age interprets her anew. To some, she is a warning against arrogance. To others, she is a saint of sorrow, a mother who suffered beyond endurance yet became one with nature itself. Some see her as a reflection of the human condition—the endless struggle between emotion and reason, between ambition and humility.

In her, we see that the line between divine and mortal, between triumph and tragedy, is razor-thin. One moment of pride can invite eternity of pain—but within that pain lies a strange kind of beauty, the beauty of feeling so profoundly that even stone must weep.

The Stone That Still Cries

If you ever find yourself near Mount Sipylus, stand before the Niobe Rock as the sun sets and the sky turns gold. Listen to the trickling water that slides down her stony cheeks. Feel the silence that surrounds her, the weight of centuries in her gaze.

You may not believe in gods or myths. You may tell yourself it is only erosion, only a coincidence of shape and shadow. But if you listen closely, you may hear something older than belief—a whisper of sorrow that belongs not to legend, but to life itself.

For Niobe’s story is not confined to ancient Greece. It lives wherever pride meets loss, wherever love turns to mourning, wherever the human heart breaks and still beats on.

She is the echo of every tragedy, the shadow behind every tear. She is the reminder that even in our lowest despair, there is something eternal—something that does not die, but endures in silence.

And so, as the last light fades, the mountain weeps again. The tears fall, softly, endlessly.

The queen is stone, but her sorrow is alive.

Niobe weeps, and through her, the world remembers what it means to be human.