What came before the universe? It is perhaps the most haunting question in all of science—a question that lingers at the border between physics and philosophy, where imagination and mathematics meet. For as long as humans have stared into the night sky, we have wondered about the beginning. How did something arise from nothing? Did time itself have a starting point, or does existence stretch eternally backward into an infinite past?

Modern physics, with all its power and precision, faces its limits at this frontier. The universe, according to our best models, began 13.8 billion years ago in an event we call the Big Bang—a moment when space, time, matter, and energy all emerged from an unimaginably dense and hot state. But the Big Bang is not just a moment of creation; it is a wall of understanding, a boundary beyond which our equations break down.

When cosmologists try to peer before this moment, they find themselves confronting the concept of “nothingness.” Yet even the word “nothing” is deceptive. In physics, nothingness is rarely absolute. What we call “nothing” often hides deep structure—fields, fluctuations, and potential waiting to burst into reality. The physics of nothingness, then, is not a study of emptiness but of the profound and fertile void from which everything came.

To explore what existed before the universe, we must ask what we mean by “before,” by “existence,” and by “nothing.” These are not just philosophical puzzles—they are the deepest questions science can ask.

The Birth of the Universe

The modern story of the universe begins with the Big Bang, a term coined half in jest by astronomer Fred Hoyle in the mid-20th century. Despite the name, it was not an explosion in space but an expansion of space itself. Everything—the galaxies, stars, planets, and even the fabric of time—was once compressed into an incredibly small, hot, and dense state.

In the first fractions of a second after this beginning, the universe underwent an extraordinary transformation. It inflated faster than the speed of light, cooling as it expanded. Energy condensed into particles, particles formed atoms, and atoms clumped into stars and galaxies. From that seething plasma, structure emerged.

But the Big Bang theory describes only the evolution of the universe after its birth—it says little about how it began or what came before. As we trace the cosmic clock backward, time itself becomes uncertain. At around (10^{-43}) seconds after the Big Bang, known as the Planck time, gravity and quantum mechanics collide. Our current theories—general relativity and quantum physics—can no longer be reconciled. This moment marks the veil beyond which physics cannot yet see.

So what, if anything, existed “before” the Big Bang? Was there truly nothing, or something we cannot yet define?

The Problem of “Before”

When we speak of “before,” we assume time exists as a continuous line stretching infinitely in both directions. But in the context of the universe’s origin, time itself may have been born alongside space and matter.

According to general relativity, time is not separate from space—it is part of a single fabric known as space-time, shaped by mass and energy. In this view, the Big Bang is not an explosion in preexisting time but the origin of time. Asking what happened before the Big Bang is like asking what lies north of the North Pole. The question dissolves because the concept of “before” loses meaning when time itself does not yet exist.

This interpretation suggests that the universe is not an event in time, but the creation of time. From the perspective of physics, the Big Bang may not be the beginning of everything, but rather a boundary beyond which time cannot extend. However, not all physicists accept this as the final word. Several theories propose that the Big Bang was not the absolute beginning but a transition—one phase in a larger cosmic cycle.

The Quantum Seeds of Reality

In the quantum realm, emptiness is never truly empty. Even in what we call a perfect vacuum, tiny fluctuations in energy constantly appear and vanish. These ephemeral events, known as quantum fluctuations, arise from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which states that energy and time cannot both be precisely defined. In other words, “nothing” cannot stay perfectly still—it seethes with potential.

This idea has profound implications for the origin of the universe. Some cosmologists propose that the universe itself could have emerged from a quantum fluctuation—a moment when the vacuum’s latent energy spontaneously gave birth to space and time. In this scenario, the universe did not require a “before” or an external cause; it arose naturally from the laws of quantum physics.

This concept, sometimes called quantum creation, was explored by physicists such as Edward Tryon, Stephen Hawking, and Alexander Vilenkin. In 1973, Tryon suggested that the universe might be a “quantum fluctuation of nothing.” Hawking later developed models where the universe could spontaneously appear with no boundary or singularity, describing the cosmos as “self-contained.”

Vilenkin expanded this view with the idea of quantum tunneling from nothing. In quantum mechanics, particles can sometimes pass through energy barriers that would be impossible classically. Similarly, the entire universe could have “tunneled” into existence from a state of absolute nothingness—a timeless, spaceless quantum vacuum governed by probabilistic laws.

In this picture, nothingness is not a void but a kind of quantum potential—a field of possibilities from which the universe could spontaneously arise.

The Inflationary Universe

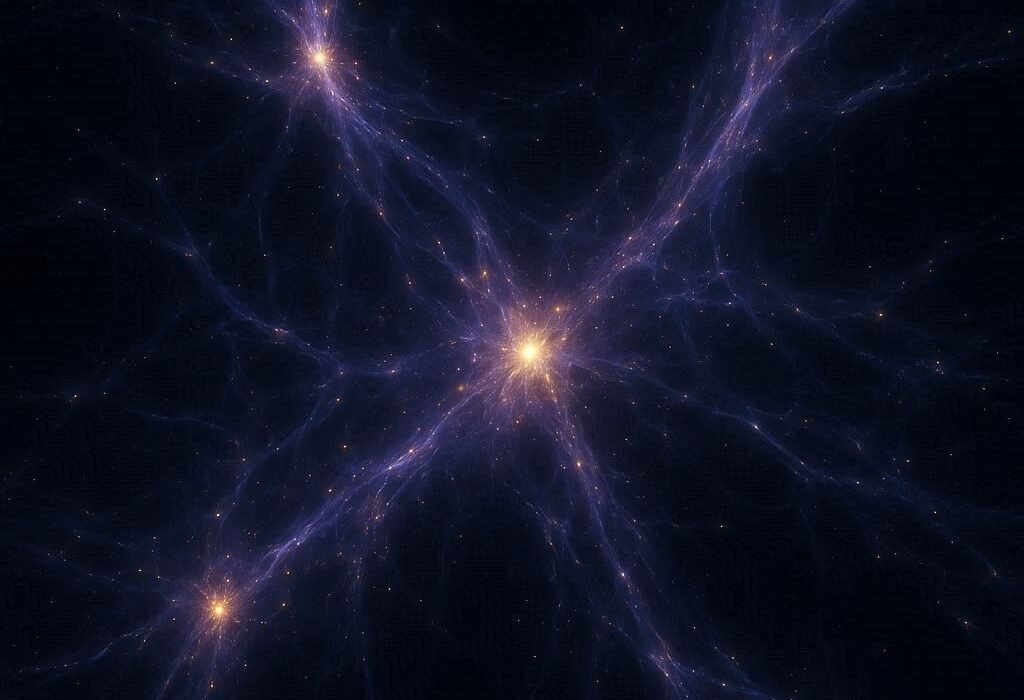

A critical development in modern cosmology was the theory of cosmic inflation, proposed by Alan Guth in 1980. Inflation explains why the universe appears uniform and flat on large scales. It posits that, in the tiniest fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe underwent a period of exponential expansion driven by a high-energy field known as the inflaton.

This inflationary period smoothed out irregularities and set the stage for the large-scale structure we see today. Tiny quantum fluctuations during inflation were stretched across cosmic distances, later becoming the seeds of galaxies. In this sense, the universe’s grand structure—clusters, stars, and planets—emerged from quantum ripples in an early vacuum.

Inflation also deepens the mystery of the beginning. Some versions of the theory suggest that inflation never completely ends. Instead, it continues eternally in some regions, creating a multiverse—a vast cosmic sea in which countless “bubble universes” like ours are constantly forming. If true, our universe might be just one bubble in an infinite froth of creation.

In this eternal inflation model, there may never have been a singular “beginning.” Instead, universes continually bud from an underlying quantum vacuum that has always existed. The question “what came before?” might thus be replaced by “what lies beyond?”

The Multiverse Hypothesis

The idea of a multiverse—the existence of many universes beyond our own—has become one of the most provocative and controversial ideas in modern physics. While it sounds like science fiction, it arises naturally from inflationary theory and quantum cosmology.

If inflation is eternal, each bubble universe can have different physical properties, constants, or even dimensions. Some may collapse in an instant; others may give rise to long-lived, stable universes like ours. In this view, the Big Bang was simply our local birth within a much larger cosmic landscape.

The multiverse could also explain the apparent fine-tuning of our universe. The physical constants—such as the strength of gravity, the charge of the electron, and the cosmological constant—seem precisely balanced to allow for the existence of stars, planets, and life. In an infinite multiverse, all possible combinations of constants occur somewhere. We find ourselves in a universe compatible with life simply because such universes are the only ones in which observers can exist—a concept known as the anthropic principle.

While direct evidence for the multiverse remains elusive, the idea reframes the question of “before the universe.” Perhaps there was no absolute beginning—only transitions between countless universes emerging and dissolving in the quantum foam of existence.

The Universe from Nothing

The phrase “a universe from nothing” gained public attention through the work of physicist Lawrence Krauss, who argued that the laws of quantum physics make creation without a creator possible. In this framework, “nothing” refers not to absolute emptiness but to a state without particles, fields, or classical space-time. Even in such a state, quantum laws persist, allowing fluctuations to give rise to universes.

However, this interpretation provokes both scientific and philosophical debate. Critics note that quantum laws themselves constitute “something”—a mathematical framework, not true nothingness. If the universe arose from the laws of physics, one might ask: where did those laws come from? Were they eternal, or did they, too, emerge from a deeper reality?

In this sense, the physics of nothingness confronts a paradox: every attempt to explain existence in terms of prior conditions seems to push the question back one level further. If the universe arose from the quantum vacuum, what gave rise to that vacuum? If time began at the Big Bang, what determined the laws governing that event? The mystery of nothingness may never be fully dissolved because the concept itself resists absolute definition.

Time Before Time

If time began with the Big Bang, what does it mean to talk about “before”? Some theories propose that time did not begin abruptly but transitioned smoothly from a prior state.

One such model is the Hartle-Hawking no-boundary proposal, developed by Stephen Hawking and James Hartle in the 1980s. They suggested that, at the earliest moments of the universe, time may have behaved like a spatial dimension. Instead of a sharp beginning, time “curved” smoothly into space, eliminating the singularity. In this view, the universe is finite but has no boundary—like the surface of a sphere that has no edge. Asking what happened before the Big Bang would be as meaningless as asking what lies beyond the edge of a globe.

Other approaches, such as loop quantum cosmology, suggest that the Big Bang was actually a “Big Bounce.” According to this idea, a previous universe collapsed under gravity, reaching an extremely dense state before rebounding into expansion. In such models, the universe could be cyclic, oscillating eternally through phases of contraction and expansion.

These theories offer a striking possibility: that “before the universe” was not nothing, but another universe, another cycle, another beat in an infinite cosmic rhythm.

The Energy Balance of Creation

One of the great insights of modern cosmology is that the total energy of the universe may be zero. Matter and radiation contribute positive energy, while gravity contributes negative energy. When these balance perfectly, the universe can exist without violating conservation laws.

This concept provides a possible mechanism for creation from nothing. If the total energy of the universe is zero, then it could emerge spontaneously, just as particle-antiparticle pairs appear briefly in quantum fields. The universe, in this view, is a vast self-balancing fluctuation—a cosmic loan from the void that requires no repayment.

Alan Guth and others have described this as “the ultimate free lunch.” The laws of physics, by their very nature, may allow universes to appear without external cause. What we call “nothing” could be the seedbed of infinite creation.

The Nature of the Vacuum

In classical physics, a vacuum is empty space devoid of matter. But in quantum field theory, even empty space teems with activity. The vacuum is a dynamic entity filled with fluctuating fields and virtual particles that pop in and out of existence.

This quantum vacuum has measurable effects. It gives rise to the Casimir effect, where two uncharged metal plates placed close together experience a force due to changes in vacuum energy. It also contributes to the cosmological constant—the mysterious energy driving the accelerated expansion of the universe, often referred to as dark energy.

If our universe emerged from such a vacuum, then nothingness itself is far from barren. It is a restless sea of potential, capable of birthing entire universes. In this sense, the vacuum is not the absence of reality but its deepest foundation—a kind of quantum womb from which space and time are born.

The Limits of Understanding

The question of what existed before the universe may ultimately lie beyond the reach of empirical science. The Big Bang marks the boundary where our physical theories break down. To go further, we need a unified theory that merges quantum mechanics and general relativity—a theory of quantum gravity.

Efforts such as string theory and loop quantum gravity aim to provide this unification. String theory envisions fundamental particles as tiny vibrating strings existing in higher-dimensional space, while loop quantum gravity suggests that space itself is quantized into discrete units. Both frameworks hint that the universe’s origin may involve geometry and energy at the Planck scale, far smaller than we can probe experimentally.

Even if such a theory were achieved, it might still leave the question of ultimate origin unresolved. The laws of physics can describe how the universe evolves, but they may not explain why those laws exist or why there is something rather than nothing. At some point, science meets the limits of explanation, where metaphysics begins.

The Philosophy of Nothingness

Throughout history, philosophers have grappled with the notion of nothing. In ancient Greece, Parmenides declared that “nothing cannot exist,” while Democritus envisioned a void that allows atoms to move. In the Middle Ages, theologians debated whether creation ex nihilo—from nothing—was logically possible.

In modern times, physics has redefined nothingness. It is not an absence of being, but a ground state of potential. Yet this raises profound questions about meaning. If the universe arose naturally from quantum laws, are those laws themselves eternal? If not, where did they come from? Can the laws of nature create themselves?

Some thinkers argue that our very notion of “nothing” may be flawed—that there is no such thing as absolute nothingness. Perhaps existence is fundamental and eternal, while “nothing” is a concept that only arises from the human mind. In this view, the universe did not come from nothing because there never was a true nothing to begin with.

Cycles, Echoes, and Endless Creation

Among the most captivating ideas in cosmology is that the universe may be cyclic—a pattern of birth, death, and rebirth extending forever. Ancient philosophies from India to Greece imagined such cycles, and modern physics has revived them in new forms.

In ekpyrotic and cyclic universe models, our cosmos may have emerged from the collision of higher-dimensional “branes”—membranes existing in a larger space. Each collision triggers a Big Bang, followed by expansion and eventual contraction, setting the stage for the next cycle.

Loop quantum cosmology offers a different picture, in which the universe contracts to a finite density and then rebounds—a Big Bounce instead of a singular beginning. In such scenarios, there was no absolute beginning, only eternal transformation. The cosmos, in its deepest nature, may be timeless—a self-renewing process without origin or end.

The Human Need to Know

Why do we ask what came before the universe? Perhaps because the question touches something primal—a longing to understand our place in the infinite. To contemplate nothingness is to confront the limits of knowledge, the edges of being. It reminds us that science, for all its triumphs, still operates within the boundaries of time and observation.

And yet, this search reveals something profound about human curiosity. We are creatures who can imagine the void, who can ask why there is something rather than nothing. In that act of questioning lies our connection to the universe itself. We are the cosmos made conscious, trying to remember its own beginning.

The Eternal Mystery

In the end, the physics of nothingness may never yield a final answer. Whether the universe arose from quantum fluctuations, from a previous cycle, or from some timeless state beyond comprehension, we remain embedded within it—unable to step outside and observe its birth.

What existed before the universe? Perhaps nothing. Perhaps everything. Perhaps something so different that our words fail to describe it.

But there is a deeper truth in our quest: that even if the universe had a beginning, the desire to understand it is itself eternal. Every atom in our bodies was forged in ancient stars, every thought a ripple of cosmic history. We are not separate from the universe’s origin—we are its unfolding story.

The physics of nothingness, then, is not about emptiness at all. It is about the infinite potential woven into the fabric of reality—the strange and wondrous fact that out of the quiet of the void came stars, galaxies, and minds capable of asking why.

To gaze into the mystery before time is to realize that nothingness may be the most profound something of all. And in that realization, we glimpse not an end to our questions, but their beginning—a spark of understanding rising, once more, from the silence that birthed the universe.