Long before the first cities rose, before written language, before even the earliest human footsteps pressed into soft earth, the planet was alive in ways that now feel almost unreal. Forests stretched farther than imagination, seas teemed with creatures stranger than myths, and continents drifted through climates so extreme they reshaped life itself. This was the prehistoric world, a vast and ancient stage where life experimented endlessly, producing forms so alien that they feel like dreams rather than ancestors.

And yet, most of that world is gone.

Not merely changed, not gently transformed, but erased. Entire ecosystems vanished without leaving written records, songs, or monuments. Their stories survive only as fragments trapped in stone, chemical signatures in rock layers, and faint genetic echoes carried by modern life. The prehistoric world did not end in a single moment. It faded through a series of catastrophes, slow declines, sudden extinctions, and profound transformations that reshaped Earth again and again.

To understand this vanished world is to confront a truth that is both humbling and unsettling: extinction is the rule, survival the exception. The planet we know today is not the natural endpoint of history but a temporary arrangement in an ongoing cycle of creation and loss.

The Deep Time Before Memory

Prehistory stretches so far back that ordinary language struggles to contain it. Millions of years blur into each other, and even a thousand years becomes an insignificant blink. Earth itself is more than four and a half billion years old, and life appeared relatively early in that immense timeline. For most of its existence, life remained microscopic, invisible to the naked eye yet powerful enough to reshape the planet’s atmosphere and oceans.

These earliest organisms transformed Earth in silence. They produced oxygen, altered ocean chemistry, and laid the foundation for complex life. There were no witnesses, no predators stalking prey, no forests whispering in the wind. And yet, without this invisible prehistoric world, nothing that followed would have been possible.

As time passed, life diversified. Simple cells merged into complex ones. Multicellular organisms emerged, experimenting with form and function. Soft-bodied creatures filled ancient seas, many of them leaving no fossils behind. Entire branches of life appeared and vanished before bones or shells ever evolved. Their existence is inferred only through chemical traces and subtle distortions in ancient rocks.

This is the first vanished world, one erased almost completely, known only through indirect clues. It reminds us that what we know of prehistory is not a full record but a scattered archive, with most pages missing.

The Rise of Ancient Seas and Lost Oceans

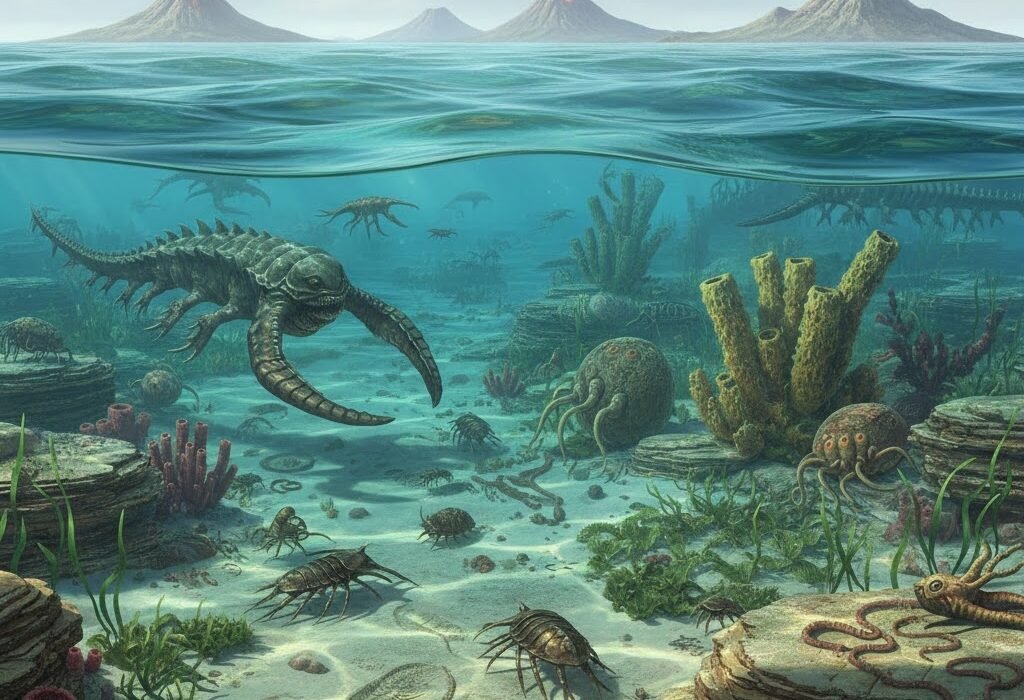

When complex life finally exploded into visible abundance, it did so in the oceans. The seas of the prehistoric world were nothing like those of today. They were warmer, chemically different, and filled with creatures that defy modern classification.

During the Cambrian period, life underwent a dramatic expansion. Animals with hard shells, segmented bodies, compound eyes, and unfamiliar anatomies appeared in a geological instant. Many of these creatures belonged to evolutionary experiments that would not last. They thrived briefly, then disappeared, leaving behind fossils that look like visitors from another planet.

Ancient seas were ruled by predators with grasping appendages and circular mouths lined with teeth. Trilobites scuttled across seafloors, dominating for hundreds of millions of years before vanishing entirely. Reef systems formed from organisms unlike modern corals, only to collapse and be replaced by new reef builders again and again.

Whole ocean ecosystems rose and fell as sea levels changed and continents shifted. When seas retreated, marine life was stranded, suffocated, or forced to adapt. When oceans returned, they brought new conditions that favored different survivors. The prehistoric oceans were dynamic and unforgiving, places of constant change where dominance was always temporary.

Most of these ancient marine worlds are gone without a trace visible to casual observation. Their seabeds are now mountain ranges. Their coral cities crushed into limestone. Their inhabitants reduced to impressions in rock, if they survived at all.

The First Green Continents That No Longer Exist

For much of Earth’s history, land was barren. Then plants arrived, quietly transforming the planet. Early land plants were small and fragile, clinging to damp environments. Over time, they grew taller, stronger, and more complex, creating the first forests.

These prehistoric forests were unlike anything alive today. Towering club mosses and giant horsetails formed dense wetlands. Trees without flowers or seeds reproduced through spores, filling the air with clouds of reproductive dust. Insects grew to enormous sizes, supported by oxygen-rich air. Millipedes stretched longer than modern humans are tall.

These ecosystems reshaped Earth’s climate. Plants drew carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locked it into their tissues. When they died, many were buried rather than decomposed, eventually becoming coal. This process cooled the planet and altered global weather patterns.

And then, many of these forests disappeared.

Climate shifts dried wetlands. Ice ages advanced and retreated. Continents collided, raising mountains and draining lowlands. The once-dominant plant lineages dwindled, replaced by seed-bearing plants better suited to harsher conditions. The great coal forests collapsed, leaving behind vast deposits of fossilized carbon and little else.

What remains of these vanished green worlds are coal seams and scattered fossils, silent evidence of ecosystems that once stretched across continents.

When Life Conquered the Land and Paid the Price

Animals followed plants onto land, evolving lungs, limbs, and new ways of surviving outside water. Amphibians thrived first, followed by reptiles that no longer depended on moist environments for reproduction. This transition opened the door to an explosion of terrestrial life.

The prehistoric land was filled with creatures that no longer exist. Massive amphibians lurked in swamps. Early reptiles experimented with body plans that would later vanish. Some lineages grew dominant, only to be wiped out by environmental upheaval.

One of the defining features of prehistory is how often success led to extinction. Species adapted perfectly to specific conditions, becoming specialists. When those conditions changed, specialization became a liability. Those unable to adapt quickly enough disappeared.

These extinctions were not always sudden. Some unfolded over millions of years, a slow decline as habitats shrank and resources dwindled. Others were abrupt, triggered by volcanic eruptions, climate shocks, or sudden drops in oxygen levels.

The land itself was unstable. Continents drifted, merged, and split apart. Mountain ranges rose and eroded. Rivers changed course. The ground beneath prehistoric creatures was never truly permanent.

The Forgotten Ice Ages Before the Famous Ones

When people think of ice ages, they often imagine mammoths and glaciers creeping across northern lands. But Earth experienced multiple ice ages long before humans appeared, each one erasing vast portions of the prehistoric world.

Some ice ages were global, covering much of the planet in ice. Others were regional but still devastating. Ice locked up water, lowering sea levels and destroying coastal ecosystems. As glaciers advanced, they scraped landscapes clean, grinding forests, soils, and fossils into dust.

Life survived by retreating, adapting, or enduring in refuges near the equator or in deep oceans. When the ice retreated, the world that emerged was different. Species that had dominated before were often gone, replaced by those better suited to colder or more variable climates.

These cycles of freezing and thawing reshaped evolution. They favored resilience over dominance and flexibility over specialization. Entire prehistoric communities vanished beneath ice, leaving behind landscapes that would later be recolonized by new life.

The Great Extinctions That Reset the Planet

Several times in Earth’s history, life came close to collapse. These mass extinctions mark the most dramatic vanishing acts of the prehistoric world. They did not simply remove individual species but dismantled entire ecosystems.

One of the most devastating occurred at the end of the Permian period, when volcanic activity released enormous amounts of greenhouse gases. Oceans became acidic and oxygen-poor. Temperatures soared. An estimated ninety percent of marine species and seventy percent of land species vanished. Forests disappeared, and for millions of years, Earth was dominated by sparse, struggling life.

Another mass extinction ended the reign of the dinosaurs. A massive asteroid impact combined with volcanic activity triggered rapid climate change. Sunlight was blocked, temperatures dropped, and food chains collapsed. The dominant animals of the prehistoric world vanished, clearing ecological space for mammals to rise.

These extinctions were not merely destructive. They were creative in a cruel way. By wiping the slate clean, they allowed new forms of life to emerge. The world that followed was never the same as the one that vanished.

The Lost Giants of Prehistory

Among the most emotionally powerful losses of the prehistoric world are the giants. Massive animals once walked, swam, and flew across Earth. Some weighed more than modern airplanes. Others stretched longer than city buses.

Dinosaurs were only part of this story. Giant marine reptiles ruled ancient seas. Enormous insects buzzed through coal forests. Later, mammals grew to astonishing sizes, filling ecological roles left vacant by reptiles.

These giants were products of specific conditions. Warm climates, abundant resources, and evolutionary pressures favored size. When those conditions changed, gigantism became unsustainable. Large animals require large amounts of food and stable environments. When ecosystems fragmented or climates shifted, giants were often the first to fall.

Their disappearance reshaped ecosystems. Predation patterns changed. Vegetation grew differently. Smaller, more adaptable species took over. The world became quieter, less dominated by titanic forms.

What remains are bones embedded in rock and the human imagination struggling to comprehend creatures so vast.

The Vanished Sounds, Colors, and Behaviors

One of the most haunting aspects of the prehistoric world is what cannot be fossilized. Fossils preserve shape but not sound, color, or behavior. We will never hear the calls of extinct animals or see the true colors of ancient forests.

Many prehistoric creatures likely displayed vibrant patterns, used complex vocalizations, and engaged in social behaviors as rich as those of modern animals. Entire communication systems vanished without record. Courtship rituals, migration routes, and learned behaviors disappeared along with the species that practiced them.

Even when bones remain, much of the story is lost. Fossils are biased toward certain environments and organisms. Soft-bodied creatures, delicate plants, and entire ecosystems left little trace. The prehistoric world we reconstruct is incomplete, a shadow of what once existed.

This loss is not just scientific but emotional. It reminds us that most of Earth’s beauty existed only in its moment, unrecorded and unremembered.

How Climate Shaped the Disappearing World

Climate is one of the most powerful forces in prehistoric history. Shifts in temperature, rainfall, and atmospheric composition repeatedly redrew the map of life.

Warm periods allowed forests to spread into polar regions. Cold periods compressed life toward the equator. Changes in ocean circulation altered nutrient flows, triggering booms and collapses in marine ecosystems.

Unlike modern climate change, prehistoric climate shifts often unfolded over tens of thousands or millions of years. Yet even slow changes can be devastating when they cross critical thresholds. Species adapted to narrow ranges found themselves trapped between advancing deserts and retreating forests.

Climate change did not act alone. It interacted with volcanism, tectonics, and biological evolution. Together, these forces erased worlds and built new ones on their remains.

The Fragile Record of What Once Was

The prehistoric world vanished not only because life went extinct, but because the Earth itself is constantly recycling. Rocks melt, sediments compress, and tectonic plates subduct entire landscapes back into the mantle. Fossils are destroyed as often as they are created.

What we know of prehistory comes from rare moments when conditions were just right for preservation. A sudden burial. An anoxic seabed. A rapid mineralization. These moments captured fragments of ancient life and protected them through deep time.

This means that the prehistoric world we reconstruct is deeply incomplete. For every fossil found, countless organisms lived and died without trace. Entire ecosystems may have existed in environments that left no geological record.

The vanished world is larger than the known one, and much of it is permanently beyond recovery.

The Transition Toward a Familiar Earth

As prehistory moved closer to the present, ecosystems began to resemble those we recognize today. Flowering plants spread. Modern insect groups diversified. Mammals evolved into more familiar forms.

Yet even in this more recognizable world, loss continued. Many large mammals vanished near the end of the last ice age. Climate change and human activity likely combined to drive these extinctions. Mammoths, giant ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats disappeared, taking with them the last echoes of a truly prehistoric Earth.

The landscapes they shaped changed in their absence. Vegetation patterns shifted. Fire regimes altered. Ecosystems reorganized. The world humans inherited was already missing key players.

What the Vanished World Teaches Us

The prehistoric world that vanished without a trace offers lessons written in stone. It shows that life is resilient but not invincible. It demonstrates that dominance is temporary and that change is inevitable.

It also reveals the deep interconnectedness of life and environment. Climate, geology, and biology are inseparable. When one shifts, the others respond, sometimes with catastrophic consequences.

Perhaps most importantly, prehistory teaches humility. Humans are newcomers in a story billions of years old. The Earth has endured far greater upheavals than anything we have yet experienced, and it will continue long after we are gone.

Standing at the Edge of Another Vanishing World

Today, we live in a world shaped by the ghosts of prehistory. Coal forests power our cities. Ancient plankton forms the basis of fossil fuels. The bones of extinct giants fill museums, reminding us of what once was.

At the same time, we are witnessing changes that echo prehistoric patterns. Climate is shifting. Species are disappearing. Ecosystems are fragmenting. The difference is that this time, one species understands what is happening.

The prehistoric world vanished without knowing it was ending. We do not have that excuse.

To study the vanished worlds of the past is not merely to indulge curiosity. It is to recognize that the Earth has always been dynamic, always changing, and that loss is woven into the fabric of life. Whether the future holds another great vanishing depends, in part, on what we learn from the worlds that disappeared before us.

The prehistoric world is gone, but its story is still speaking, if we are willing to listen.