Earth today feels familiar to us. Forests, oceans, insects, birds, mammals, and humans form a world that seems stable and recognizable. Yet this familiarity is an illusion created by a very brief moment in deep time. For most of Earth’s history, the planet was ruled by life forms so strange that, if encountered today, they would appear almost alien. Long before humans, before mammals, before even trees, the planet belonged to organisms with unfamiliar bodies, unfamiliar metabolisms, and unfamiliar ways of interacting with their environment. These beings dominated Earth for millions, sometimes hundreds of millions of years, shaping the planet’s atmosphere, oceans, and geology in ways that still define the world we inhabit.

Understanding these ancient life forms is not merely an exercise in curiosity. It is a way of understanding how life evolves, how ecosystems transform, and how fragile dominance can be. The fossil record tells a story of repeated rise and fall, where no group remains supreme forever. What follows is a scientifically grounded exploration of the strange organisms that once ruled Earth, reconstructed from rocks, fossils, chemical signatures, and modern evolutionary biology.

A World Before Familiar Life

For nearly the first three billion years of Earth’s history, complex animals did not exist at all. The planet was dominated by microscopic life, organisms that would be invisible to the naked eye yet immensely powerful in their collective impact. Bacteria and archaea were the original rulers of Earth, and in many ways, they still are. These microorganisms formed vast microbial mats, altered the chemistry of the oceans, and transformed the atmosphere itself.

Among the most influential were cyanobacteria, often misleadingly called blue-green algae. These organisms developed oxygenic photosynthesis, a process that releases oxygen as a byproduct. Over immense spans of time, this oxygen accumulated in the atmosphere during an event known as the Great Oxidation Event, fundamentally changing Earth’s environment. Oxygen was toxic to many early life forms, driving mass extinctions among anaerobic organisms, while simultaneously enabling the evolution of more complex life.

This microbial world was strange not because it was simple, but because it operated according to rules unfamiliar to modern animals. Many early organisms used chemical energy rather than sunlight, thriving near hydrothermal vents or within mineral-rich sediments. Life did not need eyes, limbs, or nervous systems to dominate the planet. It needed only chemistry, adaptability, and time.

The Ediacaran Enigma

Around 575 million years ago, Earth witnessed the appearance of some of the most enigmatic life forms ever discovered. The Ediacaran biota, named after the Ediacara Hills of Australia where they were first identified, represent the earliest known large, multicellular organisms. These creatures do not fit neatly into any modern animal group, and their biology remains the subject of active scientific debate.

Ediacaran organisms were soft-bodied and often exhibited fractal or quilted patterns. Some were shaped like discs anchored to the seafloor, others resembled elongated leaves or branching networks. They lacked obvious mouths, limbs, or sensory organs. Many appear to have absorbed nutrients directly from seawater, rather than feeding in the ways familiar to modern animals.

For tens of millions of years, these organisms dominated shallow marine ecosystems across the globe. Fossils have been found on multiple continents, indicating that they were widespread and ecologically successful. Yet most of them vanished before or during the Cambrian Period, leaving no direct descendants. Their extinction may have been driven by environmental changes, the evolution of predation, or competition from emerging animal groups.

The Ediacaran world reminds us that dominance does not require aggression or complexity as we define it today. These organisms flourished in a stable environment that favored passive, surface-dwelling life. When conditions changed, their strange forms were no longer viable.

The Cambrian Explosion and Experimental Bodies

The Cambrian Period, beginning around 541 million years ago, marks one of the most dramatic transitions in the history of life. Over a relatively short geological interval, an extraordinary diversity of animal forms appeared. This event, known as the Cambrian explosion, produced creatures with hard shells, jointed limbs, complex eyes, and active modes of life.

Many Cambrian animals are startlingly strange by modern standards. Anomalocaris, one of the top predators of its time, had large compound eyes, spiny grasping appendages, and a circular mouth lined with sharp plates. Hallucigenia, once reconstructed upside down due to its bizarre anatomy, possessed long spines along its back and tentacle-like legs beneath its body. Opabinia featured five eyes and a flexible proboscis ending in a claw.

These organisms represent an era of evolutionary experimentation. Body plans were being tested in countless variations, many of which did not survive beyond the Cambrian. While some lineages gave rise to modern groups such as arthropods, mollusks, and chordates, others disappeared entirely, leaving only fossils as evidence of their existence.

The Cambrian seas were dynamic, competitive environments where vision, mobility, and predation reshaped ecosystems. Life was no longer confined to passive existence on the seafloor. It moved, hunted, defended itself, and altered the evolutionary trajectory of the planet.

The Age of Invertebrate Empires

Long before vertebrates rose to prominence, invertebrates ruled Earth’s oceans. Trilobites, arthropods with segmented bodies and hard exoskeletons, were among the most successful animals in Earth’s history. They appeared during the Cambrian and persisted for over 250 million years, surviving multiple mass extinctions before ultimately disappearing at the end of the Permian Period.

Trilobites exhibited remarkable diversity. Some were streamlined swimmers, others burrowed into sediment, and some developed elaborate spines and ornamentation. Their compound eyes, preserved in extraordinary detail in the fossil record, reveal sophisticated visual systems adapted to a wide range of environments.

Other invertebrate groups also dominated ancient seas. Brachiopods, superficially similar to clams but anatomically distinct, formed dense populations on the seafloor. Crinoids, relatives of starfish, rose on stalks like underwater flowers, filtering food from passing currents. Eurypterids, often called sea scorpions, included species that grew over two meters long and occupied top predator roles in coastal ecosystems.

These invertebrate empires shaped marine environments for hundreds of millions of years. Their rise and eventual decline underscore how dominance is always temporary, contingent on environmental stability and evolutionary flexibility.

When Fish Ruled the Waters

The Devonian Period, often called the Age of Fishes, saw vertebrates emerge as major players in Earth’s ecosystems. Jawless fish had existed earlier, but the evolution of jaws revolutionized feeding strategies and ecological interactions. Armored placoderms, some of which reached enormous sizes, became apex predators in ancient seas.

Placoderms such as Dunkleosteus possessed massive bony head shields and powerful jaws capable of crushing prey. Their success was built on anatomical innovation, yet they vanished entirely by the end of the Devonian. Other fish groups, including early sharks and bony fish, survived and diversified, eventually giving rise to all modern vertebrates.

During this period, fish also began exploring freshwater environments, rivers, and lakes. Some developed lobed fins with internal bone structures that allowed them to support their bodies in shallow water. These adaptations would later prove crucial for one of the most transformative events in evolutionary history: the colonization of land.

The First Rulers of the Land

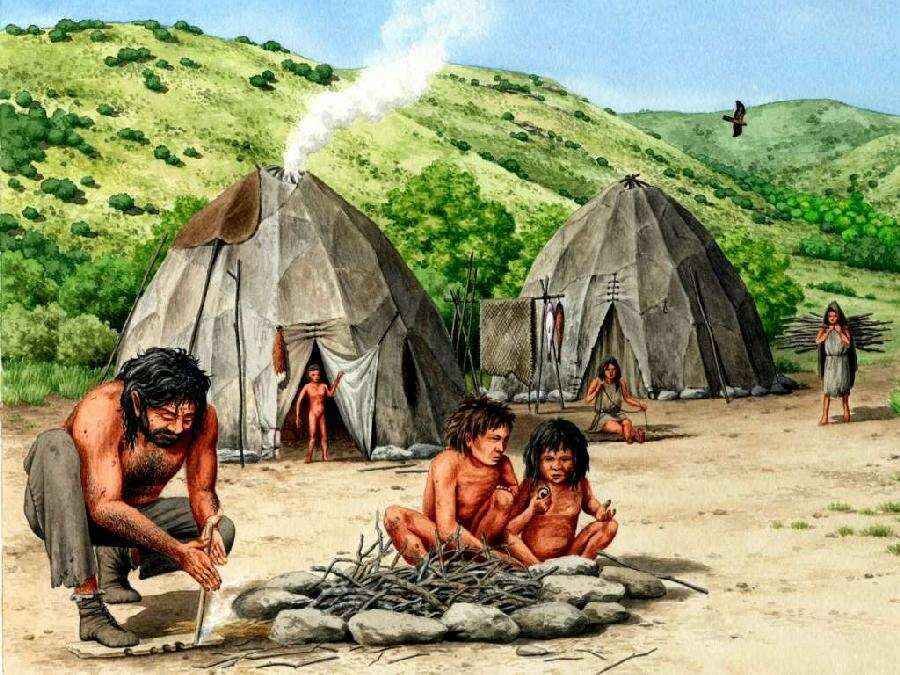

When vertebrates first ventured onto land, the terrestrial world was radically different from today. There were no flowering plants, no grasses, and no forests as we know them. Early land ecosystems were dominated by moss-like plants, ferns, and towering clubmosses. In this environment, amphibian-like tetrapods became the first vertebrate rulers of land.

These early tetrapods were often large, sprawling creatures that relied on moist environments to survive. Their life cycles remained tied to water, but they could hunt and move on land, opening vast new ecological opportunities. For tens of millions of years, they occupied dominant roles in terrestrial ecosystems.

Alongside them, enormous arthropods thrived. Giant millipedes over two meters long crawled through Carboniferous forests, while dragonfly-like insects with wingspans approaching seventy centimeters patrolled the skies. Elevated atmospheric oxygen levels likely enabled these extreme sizes, creating a world that would feel profoundly alien today.

The Rise of Reptilian Worlds

The evolution of the amniotic egg allowed vertebrates to break free from their dependence on water for reproduction. This innovation gave rise to reptiles and their relatives, which soon diversified and spread across the planet. During the Permian Period, synapsids, often called mammal-like reptiles, became the dominant land vertebrates.

These creatures included predators with saber-like teeth and herbivores with complex chewing mechanisms. Some synapsids developed upright postures and advanced metabolic features, foreshadowing later mammalian traits. For millions of years, they dominated terrestrial ecosystems.

This world came to an abrupt end during the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, the most severe extinction event in Earth’s history. Massive volcanic eruptions, climate instability, and oceanic anoxia eliminated an estimated ninety percent of marine species and seventy percent of terrestrial vertebrates. Dominant life forms vanished, clearing the stage for a new order.

Dinosaurs and the Reign of Reptilian Giants

In the aftermath of the Permian extinction, dinosaurs emerged as the most iconic rulers Earth has ever known. For over 160 million years, they dominated terrestrial ecosystems, evolving into an astonishing array of forms. Some were colossal herbivores with necks stretching over treetops, others were swift, intelligent predators with keen senses.

Dinosaurs were not the sluggish, cold-blooded creatures once imagined. Modern research indicates that many had high metabolic rates, complex behaviors, and, in some cases, feathers. They occupied nearly every ecological niche available on land, from burrowing species to apex predators.

Their dominance extended beyond land. Pterosaurs ruled the skies as the first vertebrates capable of powered flight, while marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs dominated the oceans. This was a truly reptilian world, diverse, dynamic, and globally distributed.

The end of the dinosaurs, caused by a massive asteroid impact combined with volcanic activity, once again demonstrated the fragility of dominance. A sudden environmental shock erased ruling lineages and reshaped the future of life.

The Age of Mammalian Ascendancy

With the disappearance of non-avian dinosaurs, mammals rapidly diversified. Once small, nocturnal creatures living in the shadows, mammals expanded into vacant ecological roles. Over millions of years, they evolved into forms ranging from tiny bats to massive terrestrial herbivores and fully aquatic whales.

This era saw the rise of strange mammalian giants. Mammoths roamed icy landscapes, saber-toothed cats stalked prey with elongated canines, and ground sloths grew as large as elephants. Many of these animals dominated their ecosystems until relatively recent times, disappearing only tens of thousands of years ago.

Although mammals are the current dominant large animals on land, their reign is geologically brief. Like all previous rulers, they exist within a dynamic system shaped by environmental change and extinction.

Lessons from Lost Worlds

The strange life forms that once dominated Earth reveal a fundamental truth about life’s history: there is no permanent ruling class. Dominance is shaped by innovation, environment, and chance. What seems inevitable in one era becomes impossible in another.

These ancient organisms were not evolutionary failures. They were successful within their own contexts, thriving for millions of years under conditions very different from today. Their disappearance does not diminish their significance. Instead, it highlights the contingent nature of evolution, where survival depends on both adaptation and circumstance.

By studying these lost worlds, physics, chemistry, geology, and biology converge to tell a unified story of Earth as a changing system. Fossils are not just remnants of the past; they are messages written in stone, reminding us that the present is temporary and that life, in all its strangeness, is endlessly inventive.

A Planet Shaped by Strangeness

Earth’s history is not a straight line leading inevitably to modern life. It is a branching, twisting narrative filled with experiments that succeeded, flourished, and vanished. The strange life forms that once dominated the planet were as real, as complex, and as alive as anything that exists today.

To understand them is to understand that our world is not the only possible outcome of evolution. It is one version among countless others that might have been. This realization expands our sense of wonder and deepens our appreciation for the fragile moment we now inhabit.

In the vast span of geological time, humanity occupies only an instant. The strange rulers of the past remind us that Earth does not belong to any single species forever. Life will continue to change, to adapt, and to surprise, long after today’s dominant forms have become fossils themselves.