In the heart of Greek mythology lies a tale that is not merely about gods clashing for power, but about the very shift of an age. The Titanomachy, the war between the elder gods known as the Titans and their younger successors, the Olympians, is one of the most powerful and enduring stories of human imagination. It is not simply a myth about violence—it is a narrative about transition, destiny, and the eternal struggle between the old order and the new.

When ancient poets and storytellers spoke of this war, they were not only recounting battles between divine beings; they were articulating something much deeper about the cosmos, about history, and about the human condition itself. The Titanomachy was both a mythic drama and a metaphor for change, echoing the ways civilizations shift from one era to another, where youth challenges age, and renewal emerges from destruction.

To understand the Titanomachy is to step into the timeless world of Greek mythology, where gods embody forces of nature, human qualities, and cosmic principles. It is to witness a story that, though wrapped in myth, continues to resonate with every generation that confronts the inevitability of change.

The Titans: Children of the Primordial

Before the Olympians, before Zeus and his thunderbolt, before the temples and hymns, there were the Titans. They were not the first beings in creation—that honor belonged to Chaos, Gaia (Earth), Tartarus, and Eros—but they were among the most formidable. Born of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky), the Titans were colossal figures who embodied both the creative and destructive powers of the cosmos.

The Titans were twelve in their primary form: Oceanus, Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Tethys, and Cronus. Each represented elemental or conceptual forces—Hyperion was the Titan of heavenly light, Themis embodied divine law, Mnemosyne personified memory, and Oceanus was the endless stream that circled the world. They were vast, primal, and ancient, not human-like rulers but embodiments of existence itself.

Cronus, the youngest, would rise to dominance by overthrowing his father Uranus. But in doing so, he set in motion the cycle of generational conflict that would define the cosmos. The Titans were the rulers of the Golden Age, a time described by poets as one of peace and prosperity, when mortals lived in harmony with nature. Yet beneath this age of abundance was a tension, for power seized by force rarely rests peacefully.

The Rise of Cronus and the Prophecy of Doom

Cronus, cunning and ambitious, was not content to live under the shadow of Uranus. Encouraged by Gaia, who had grown resentful of Uranus for imprisoning some of her children—the fearsome Hecatoncheires (hundred-handed giants) and the Cyclopes—Cronus seized a sickle of adamant and ambushed his father. With a single act of violence, he castrated Uranus, separating Sky from Earth and declaring himself the new ruler of the cosmos.

This act of rebellion was both a triumph and a curse. From the blood of Uranus spilled upon the earth came the Furies, the Giants, and the ash-tree nymphs. From his severed flesh thrown into the sea arose Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty. The cosmos was forever changed.

Cronus married his sister Rhea, and together they ruled during what was remembered as a golden time. But a prophecy, born from the lips of Uranus and Gaia, shadowed his reign: just as he had overthrown his father, so too would one of his children overthrow him.

Terrified of this fate, Cronus turned to ruthless measures. As each child was born, he swallowed them whole. Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon—all were consumed by their father before they could draw their first breath of freedom. Only one child would escape his hunger, hidden by Rhea’s cunning and destined to fulfill the prophecy: Zeus.

The Birth of Zeus and the Spark of Rebellion

When Zeus was born, Rhea, desperate to save her child, sought help from Gaia. Together they devised a plan. Rhea wrapped a stone in swaddling clothes and gave it to Cronus, who, deceived, swallowed it whole. Meanwhile, the infant Zeus was carried to the island of Crete, where he was hidden in a cave on Mount Ida.

There, depending on the version of the myth, he was raised by nymphs, nourished by the goat Amalthea, and protected by the Curetes, warriors who clashed their shields and spears to drown out the cries of the infant god.

Zeus grew swiftly, nourished by destiny as much as by milk and honey. He became strong, cunning, and determined, embodying both the natural might of the storm and the cleverness of a strategist. When he reached maturity, he returned to confront his father.

With the help of Metis, the goddess of wisdom, Zeus tricked Cronus into drinking a potion that caused him to vomit up his swallowed children. From the depths of Cronus emerged Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon, fully grown and burning with anger. The siblings, united for the first time, declared war.

Thus began the Titanomachy—a war that shook heaven, earth, and the very foundations of the cosmos.

The Battlefield of the Cosmos

The Titanomachy was no ordinary war. It was a battle that spanned the breadth of creation itself, fought not with mortal weapons but with forces elemental and divine.

On one side stood the Titans, led by Cronus. Loyal to him were many of his siblings, beings of immense size and strength, embodiments of the ancient cosmic order. They fought to preserve their reign, believing themselves the rightful rulers of the universe.

On the other side stood the Olympians, the children of Cronus—Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Hera, Demeter, and Hestia. They were joined by unlikely allies: the Cyclopes, freed from their prison by Zeus, who forged for him the thunderbolt, for Poseidon the trident, and for Hades the helmet of invisibility. They were also aided by the Hecatoncheires, whose hundred arms hurled mountains and whose strength shook the heavens.

The battlefield was both literal and symbolic. Mount Othrys served as the stronghold of the Titans, while Mount Olympus rose as the bastion of the Olympians. The war raged for ten years, with neither side able to secure victory, the clash of gods echoing across heaven and earth.

The Turning of the Tide

For years the battle dragged on, thunder shaking the skies and earth trembling under the weight of combat. But the tide began to turn when Zeus unleashed the full force of the weapons crafted by the Cyclopes. His thunderbolts split the heavens, Poseidon’s trident shattered the seas, and Hades’ helmet rendered him unseen, striking terror into the hearts of the Titans.

The Hecatoncheires, with their hundred arms, rained destruction upon the Titan ranks, overwhelming even the mightiest of Cronus’ allies. The old order, though powerful, could not withstand the fury of the new.

At last, the Titans were defeated. Zeus and his siblings emerged triumphant, not just as victors in battle but as the new rulers of the cosmos. The age of the Titans had ended; the age of the Olympians had begun.

The Fate of the Titans

Victory did not mean annihilation, but it did mean punishment. The defeated Titans were cast down into Tartarus, the deep abyss beneath the earth, a place darker than night where the Hecatoncheires stood guard. It was a prison from which no escape was possible, a fitting end for those who once sought to rule eternity.

Not all Titans were condemned, however. Some, like Oceanus and Themis, had not taken part in the war and were spared. Others, such as Prometheus and Epimetheus, chose to side with Zeus and were honored rather than punished. In this way, the myth reflected a nuanced vision of justice, where loyalty and choice could alter destiny.

The Dawn of the Olympians

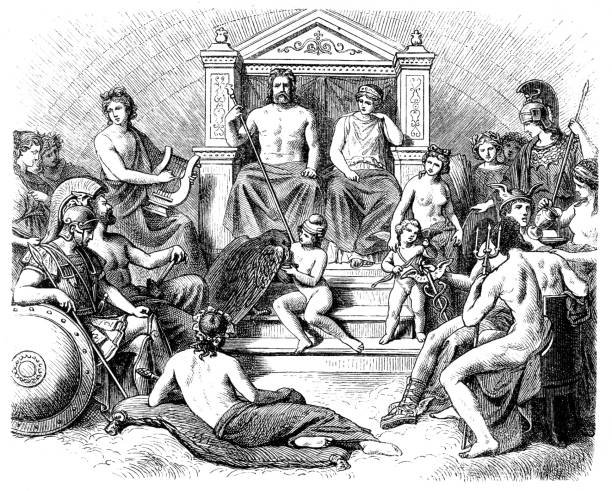

With the Titans subdued, Zeus and his siblings claimed dominion over the universe. They divided the realms among themselves: Zeus took the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld. Earth remained a common ground, shared by gods and mortals alike.

From their thrones on Mount Olympus, the new gods established their rule. They were not as distant or abstract as the Titans; they were closer to humanity, embodying both divine power and very human passions. They quarreled, loved, betrayed, and punished, yet they also nurtured, guided, and protected.

The Titanomachy was more than a war—it was the birth of a new order. It symbolized the triumph of intelligence and cooperation over brute force, of a younger generation stepping into its destiny. It explained why the Olympians, not the Titans, came to dominate the myths, rituals, and imaginations of ancient Greece.

Symbolism and Legacy

Beneath the thunder and lightning of the Titanomachy lies profound symbolism. It is a myth of succession, reflecting the cycles of life where children replace parents, where youth challenges age, where change is inevitable. It is also a myth of order triumphing over chaos, of the cosmos moving from primal rawness to a structured hierarchy.

For the Greeks, this war explained not only the rule of the Olympians but also the nature of the universe itself. The world was not static; it was alive with conflict, struggle, and renewal. The Titanomachy echoed the transitions of human life, the rise and fall of kingdoms, and the eternal march of time.

In art, literature, and philosophy, the Titanomachy lived on. Poets like Hesiod and dramatists like Aeschylus retold the tale, while sculptors carved its scenes into temples, capturing the clash of cosmic beings in marble. Even today, it echoes in modern storytelling, where generational conflict, rebellion, and the birth of new orders remain timeless themes.

Beyond the Titanomachy: The Struggle Continues

Though the Olympians won, their reign was not without challenges. New threats would rise—the Giants in the Gigantomachy, the monster Typhon unleashed by Gaia, and countless struggles with mortals and heroes. The cycle of conflict did not end with the Titanomachy, for mythology mirrors the endless rhythms of change and resistance in the world.

The Titanomachy, however, remained the primal struggle—the war that established the foundation of myth itself. It was the thunder before the symphony of stories that Greek mythology would unfold.

The Eternal Meaning of the War of Gods

The Titanomachy endures because it is more than myth—it is metaphor. It is the story of every generation that confronts the power of the past. It is the reminder that even the mightiest can fall, that time spares no order, that renewal demands conflict.

For the ancient Greeks, it explained why Zeus ruled the heavens and why Mount Olympus was the seat of power. For us, it speaks to the universality of change, the inevitability of endings, and the hope of beginnings.

The clash of Titans and Olympians is not only about gods—it is about us. It is about the cycles in our own lives, the wars we fight between tradition and progress, between fear and hope, between who we were and who we are becoming.

And so, the Titanomachy remains timeless—not just a myth of the ancient world, but a story written into the very heart of what it means to live, to struggle, and to rise anew.