Long before the rise of modern nations, before the first European ships landed on the eastern shores or the first horse thundered across the plains, the vast expanse of North America pulsed with the energy of complex civilizations. From the Arctic tundra to the steamy Gulf Coast, from desert mesas to river valleys rich with life, entire societies thrived—only to vanish mysteriously, their histories reduced to whispers carried on the wind.

These were not the primitive nomads often caricatured in early colonial tales. They were engineers, astronomers, farmers, artists, and warriors. They built monumental architecture, created elaborate trade networks, and developed sophisticated spiritual and political systems. Yet for all their achievements, many of these tribes and cultures disappeared—some rapidly, others gradually—leaving behind haunting ruins, enigmatic carvings, and myths passed down by successor tribes.

This is the story of those ancient peoples: who they were, what they built, how they lived, and why they may have vanished. In this deep dive, we’ll unearth the lost world of America’s forgotten tribes and explore the mysteries that still defy modern understanding.

The Mound Builders: Architects of Earth and Sky

Long before steel and concrete reshaped cities, indigenous builders sculpted the very land into symbols of power, worship, and mystery. Among the most astonishing of these were the Mound Builders—peoples who flourished in the eastern half of what is now the United States, leaving behind immense earthen structures that have survived for centuries.

The cultures behind these mounds are collectively known as the Adena, Hopewell, and Mississippians. Their timelines span from about 1000 BCE to 1500 CE. Though separated by centuries, they shared a common practice: building ceremonial and burial mounds, some in simple conical shapes, others in the form of animals or vast platforms.

The Hopewell culture, centered in the Ohio River Valley, traded materials like obsidian, mica, and shells across thousands of miles. This vast trade network hints at a complex, interconnected society. Yet by around 500 CE, the Hopewell had faded, their ceremonial centers abandoned.

Later, the Mississippians rose to prominence. Their greatest city was Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis. At its height around 1100 CE, Cahokia was a sprawling metropolis of 20,000 or more, larger than London at the time. At the heart of the city stood Monk’s Mound, a massive earthen pyramid over 100 feet high. The city had plazas, palisades, suburbs, and a mysterious woodhenge aligned to solstices.

Yet by 1400 CE, Cahokia, too, was in decline. The fields grew fallow, the mounds untended. No records remain to explain why. Climate change, overpopulation, resource depletion, or warfare—any of these may have played a part. Or perhaps a spiritual upheaval shattered the foundations of their world. The answers lie buried in the soil.

Ancestral Puebloans: Masters of Stone and Sky

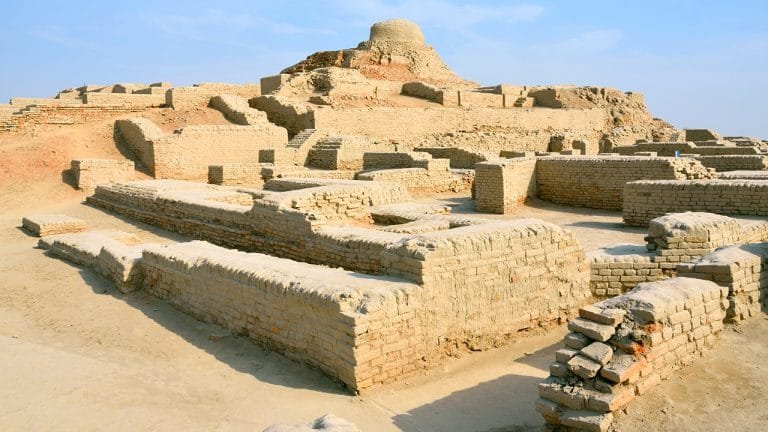

In the arid Southwest, another civilization rose, one adapted to the desert’s harsh rhythms and astonishing in its ingenuity. The Ancestral Puebloans—once known as the Anasazi—built multi-story stone dwellings that rivaled any ancient urban architecture. Their most famous homes cling to cliffs in places like Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, and Chaco Canyon.

From about 900 to 1300 CE, Chaco Canyon in New Mexico was a cultural and economic hub. Massive stone buildings, called great houses, were aligned to solar and lunar cycles. Roads, perfectly straight for miles, radiated from the canyon like spokes on a wheel. Ceremonial kivas, subterranean rooms used for rituals, suggest an elaborate spiritual life.

The engineering skill of the Puebloans is awe-inspiring. Without draft animals, metal tools, or wheeled carts, they moved tens of thousands of tons of sandstone. They farmed in a desert, using dry farming, check dams, and waffle gardens to trap moisture. They tracked celestial events with astonishing precision, as seen in the Sun Dagger of Fajada Butte.

Then, around 1300 CE, they were gone.

Cliff dwellings were abandoned. Chaco’s roads fell silent. Oral histories speak of drought, conflict, and spiritual dissatisfaction. Some believe climate extremes drove the Puebloans to seek new homes, dispersing into smaller groups that would become the modern Hopi, Zuni, and other Pueblo tribes. Their disappearance wasn’t a total vanishing—it was a transformation. But the grandeur of their cities was never again matched.

The Fremont Culture: Utah’s Forgotten People

North of the Ancestral Puebloans and west of the plains, another enigmatic culture thrived—the Fremont. Flourishing between 300 and 1300 CE in what is now Utah and parts of surrounding states, the Fremont left behind distinctive rock art, unusual granaries, and artifacts that defy easy classification.

Unlike the Puebloans, the Fremont were a blend of farmers and hunter-gatherers. They grew corn and beans but also relied heavily on wild game and foraged foods. They lived in pithouses, sometimes sheltered beneath overhanging cliffs. Their petroglyphs—stylized human figures with elaborate headgear—still peer out from red rock walls in places like Capitol Reef and Nine Mile Canyon.

The Fremont are difficult to categorize. Some archaeologists suggest they were a cultural hybrid, influenced by their neighbors but maintaining unique traditions. Their sudden disappearance around 1300 CE may have mirrored that of the Puebloans. Climate change, especially the “Great Drought” of the late 13th century, may have made farming untenable. But there are no written records, no conclusive ruins—only the eerie art and scattered remains to hint at who they were.

The Hohokam: Desert Engineers of the Southwest

In Arizona’s lowland deserts, the Hohokam civilization blossomed. From around 300 to 1450 CE, they created a vast network of irrigation canals—some stretching for miles—transforming desert into farmland. These canals, the oldest and most extensive pre-Columbian irrigation systems in North America, were dug with simple tools and bare hands.

The Hohokam grew corn, beans, squash, and cotton. They built villages of adobe and used ball courts similar to those in Mesoamerica. Their red-on-buff pottery, etched with intricate geometric patterns, is among the most distinctive in the Southwest.

By the 15th century, the Hohokam began to vanish. Their canals silted up. Villages were abandoned. No war, no disease, no conquest is clearly recorded. But subtle signs point to social upheaval. Drought may have played a role, or internal conflict. Their descendants likely merged into the O’odham peoples, whose oral histories speak of “ancient ones” who once ruled the land.

The Olmec Echo in the North?

Some theories, controversial but persistent, suggest that Mesoamerican influence extended far beyond what is currently accepted. The Olmec, Maya, and other southern cultures had written languages, sophisticated calendars, and pyramidal architecture—features that occasionally appear in surprising places in North America.

The evidence is tantalizing but inconclusive: glyphs with potential Mesoamerican resemblance, architectural similarities, and even legends among some Native tribes that speak of ancient strangers from the south. While mainstream archaeology remains skeptical, the possibility of contact across regions long before Columbus hints at a pre-Columbian world more interconnected than we imagined.

The Maritime Tribes: Legends from the Coast

Along the coasts, from the Pacific Northwest to the Florida Keys, ancient maritime cultures flourished—some of them vanishing without a trace. The Calusa of southern Florida built shell mounds and canals, living off the sea in an ecosystem few others could master. When Spanish explorers arrived in the 1500s, the Calusa were formidable, resisting conquest longer than many tribes. Yet within a century, they were gone—killed by disease, war, or absorbed by other tribes.

On the Pacific side, the Channel Islands off California held sophisticated maritime societies dating back thousands of years. They built plank canoes, traded with mainland tribes, and crafted intricate stone tools. Some scholars believe sea levels and erosion submerged parts of these cultures, leaving behind a puzzle of submerged villages and scattered bones.

The Tuniit: Ghosts of the Arctic

Far to the north, beyond the treeline, the Inuit speak of a race of giants who once lived in the Arctic—quiet people who built strong stone houses and could carry enormous weights. These were the Tuniit, or Dorset people, who lived in the Arctic from around 500 BCE to 1500 CE.

Archaeological finds confirm the existence of the Dorset culture, which preceded the Inuit and built remarkable tools, hunting implements, and carvings—many made from walrus ivory and bone. Unlike the Inuit, they did not use dog sleds or bows, relying instead on harpoons and traps.

Why the Tuniit disappeared remains unclear. Inuit legends say they were shy and withdrawn, easily displaced. Some theorize that they were unable to compete with the Inuit’s more advanced technologies. Others suggest that a cold climate shift ended their way of life. The Dorset left no known language, and few direct descendants, making them among the most mysterious of North America’s lost peoples.

Disease, Collapse, and the Great Silence

One of the great forces that erased entire tribes—often before Europeans even arrived—was disease. As early as the 1500s, plagues swept through the Americas, carried by explorers, traders, and slaves. Smallpox, influenza, and measles cut down populations that had never encountered such pathogens.

Some scholars estimate that 80–90% of Native populations in the Americas may have perished due to disease alone. Whole villages died in days, leaving no one to tell their story. Even tribes untouched by European weapons or colonization could vanish into the historical void, simply because of biological contact.

And when societies collapsed, their monuments suffered. Wood rotted. Adobe crumbled. Mounds eroded. Oral histories scattered or were lost in assimilation. What remains are the enigmatic remnants: a sun-aligned mound in Ohio, a cliff-side village in Colorado, a canal snaking through the Arizona sand.

Echoes in the Earth

Today, researchers are rediscovering these vanished tribes through archaeology, satellite imaging, and even DNA analysis. LIDAR scans of the Amazon and Mississippi Valley have revealed vast urban landscapes once thought uninhabited. Charcoal layers and pollen analysis tell of forests managed by fire, of ancient farming methods, of cycles of drought and abundance.

But beyond the science, there is something more profound: a sense of reverence. These were not just prehistoric peoples; they were humans with dreams, fears, loves, and legends. They built cities, tracked stars, healed with herbs, and buried their dead with care. Their legacy still pulses beneath the soil, in the names of rivers, in the chants of powwows, in the DNA of modern tribes.

Conclusion: The Vanishing Is Not the End

The tribes of ancient America did not all vanish. Some evolved. Some fled. Some merged into new communities. Their descendants live today in the Navajo, the Ojibwe, the Creek, the Seminole, the Hopi, the Inuit, and hundreds of other Native nations.

But many did disappear—suddenly, mysteriously, or slowly over centuries—leaving behind a riddle. Who were they? What did they know? And what might we still learn from the fragments they left behind?

As we walk the paths they carved, touch the stones they stacked, and gaze at the art they etched into canyon walls, we connect to a story far older than our textbooks suggest. The vanished tribes of ancient America are not truly gone. They are with us—in the land, in the legends, and in the enduring spirit of discovery.