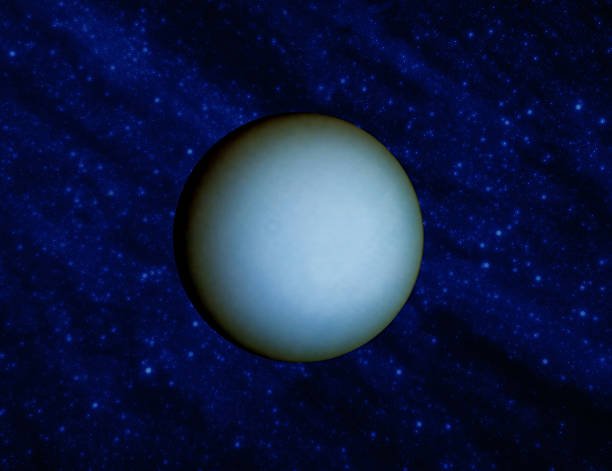

Far beyond the warmth of the Sun, past the fiery world of Venus, the stormy majesty of Jupiter, and the ringed beauty of Saturn, lies a planet so strange, so silent, that it almost feels like a secret. Uranus, the sideways ice giant, drifts through the cold reaches of space like a sleeping giant cloaked in pale blue light.

It is one of the most mysterious worlds in our solar system—a planet of frigid gases, ghostly winds, and an axis so wildly tilted that it seems to defy the laws of celestial order. For centuries, Uranus remained unseen by the naked eye, hidden among the stars, until one night in 1781, when a curious astronomer’s telescope revealed that there was more to our solar system than we had ever imagined.

Since that moment, Uranus has stood as a symbol of discovery and mystery—a place that challenges our understanding of what planets can be. It is beautiful, eerie, and profoundly alien, a world that spins on its side beneath a turquoise sky, lit by a distant, fading Sun.

The Discovery That Changed the Sky

For most of human history, only five planets were known: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. These wandering lights traced their paths across the night sky, familiar to every ancient civilization. Then, in 1781, an English astronomer named William Herschel changed everything.

While scanning the sky with his homemade telescope, Herschel spotted what he thought was a comet. But as he watched it move, he realized it was something else—something much farther away. It wasn’t a comet, and it wasn’t a star. It was a new planet—the first ever discovered with a telescope.

This was a cosmic revelation. Humanity had expanded the borders of the known solar system. The universe suddenly felt larger, and the idea that there might be even more worlds beyond ignited the imagination of scientists and dreamers alike.

Herschel proposed naming the new planet “Georgium Sidus,” or “George’s Star,” in honor of King George III, but others preferred mythological consistency. Eventually, astronomers chose the name Uranus, after the ancient Greek god of the sky and father of Saturn. The name was fitting, for Uranus truly ruled the heavens of the outer solar system—a cold, pale guardian in the dark.

A Planet That Spins Sideways

Perhaps the most astonishing feature of Uranus is its tilt. While most planets spin roughly upright relative to the plane of their orbits, Uranus lies on its side—tilted about 98 degrees. Imagine rolling a ball around the Sun not spinning like a top, but tumbling like a barrel. That’s Uranus.

This extreme tilt makes Uranus unique. It means that for part of its long, 84-Earth-year orbit, one of its poles points directly at the Sun, bathing that hemisphere in unending daylight while the other languishes in darkness for decades. Then, halfway through its orbit, the situation reverses.

The cause of this bizarre orientation is one of the great mysteries of the solar system. Most scientists believe that early in its history, Uranus was struck by a massive object—perhaps a planet-sized body—powerful enough to knock it onto its side. The collision would have forever altered the planet’s rotation, atmosphere, and possibly even its interior.

The result is a world of extremes: seasons that last over 20 Earth years, and weather patterns that defy easy explanation. Uranus is a planet frozen in a cosmic dance, endlessly rolling through space in graceful, chaotic motion.

The Ice Giant’s Ethereal Appearance

From afar, Uranus appears tranquil—a soft, blue-green sphere suspended against the black backdrop of space. Its color comes from methane gas in its upper atmosphere, which absorbs red light and reflects shades of blue and cyan. To the human eye, Uranus looks serene, almost soothing, like a distant ocean world wrapped in perpetual twilight.

But beneath that calm facade lies turbulence. The atmosphere is composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, with a trace of methane and other hydrocarbons. These gases form delicate layers, creating a hazy, opaque blanket that hides much of the planet’s true nature.

Unlike Jupiter and Saturn, which display swirling bands and storms, Uranus’s face appears bland and featureless most of the time. Yet when powerful telescopes and spacecraft have observed it under infrared light, faint cloud bands, polar storms, and even bright spots of weather activity have been revealed.

This deceptive calmness is part of Uranus’s charm. It hides its violence well—like a sleeping storm god, still and beautiful, but capable of fury beneath the veil.

The Coldest Planet in the Solar System

Despite its great distance from the Sun, Uranus should be warmer than it is. Its neighbor Neptune, farther out, actually radiates more internal heat. Yet Uranus remains strangely frigid, making it the coldest planet in the solar system.

Temperatures in its atmosphere can plunge to –224°C (–371°F). For comparison, that’s colder than the surface of Pluto at times. Scientists have long puzzled over why Uranus emits so little internal heat.

One theory suggests that the same cataclysmic impact that knocked Uranus onto its side also disrupted its interior, scattering its core’s heat and leaving the planet without an efficient way to radiate energy. Another idea is that a thin layer between the core and the atmosphere traps heat inside, preventing it from escaping.

Whatever the reason, Uranus is a world frozen in stillness—a planet so cold and quiet that its atmosphere seems almost asleep. Yet even in that silence, there is grandeur—a beauty born of isolation and the soft glow of reflected sunlight.

The Atmosphere of Blue Ice and Invisible Storms

Uranus’s atmosphere is divided into three main layers: the troposphere, stratosphere, and thermosphere. In the troposphere, weather occurs—though “weather” here means swirling clouds of methane ice and ammonia crystals, drifting in a haze of blue gas.

Deeper down, the pressure and temperature rise dramatically. At depths of thousands of kilometers, hydrogen and helium mix with water, methane, and ammonia under crushing conditions, forming a dense, icy fluid. It is this layer that gives Uranus its classification as an “ice giant.” Unlike Jupiter or Saturn, whose interiors are dominated by metallic hydrogen, Uranus is rich in icy compounds—materials that were once gases or liquids in the cold outer reaches of the solar system.

The upper atmosphere of Uranus is mysterious, with faint auroras near the poles and high-speed winds that can reach 900 kilometers per hour. These winds move in the direction of the planet’s rotation, wrapping around the globe in subtle, pale streaks invisible to the naked eye.

When Uranus’s long seasons shift, scientists believe that its weather patterns undergo vast transformations. Storms may bloom and fade, driven by sunlight that arrives in strange, long pulses as the planet rolls around the Sun. In this distant world, time itself moves differently—measured not in days or months, but in decades of light and shadow.

The Magnetic Field That Breaks the Rules

As if Uranus’s tilt weren’t strange enough, its magnetic field is equally bizarre. Most planets have magnetic fields aligned roughly with their rotational axes, but Uranus’s field is tilted about 60 degrees from its rotation axis and offset far from the planet’s center.

This means that as Uranus spins, its magnetic field wobbles wildly, creating a lopsided magnetosphere that swings and swirls like a cosmic pendulum. This uneven magnetic field creates chaotic interactions with the solar wind—the stream of charged particles from the Sun.

The result is an unpredictable dance of magnetic storms and auroras, which flicker in unexpected places, sometimes near the equator rather than the poles. The magnetic field’s strange geometry has baffled scientists for decades, and understanding it could offer new insights into the deep interiors of ice giants.

It also raises a profound question: could the magnetic fields of planets like Uranus be the key to understanding how magnetic dynamos work throughout the universe?

Rings in the Shadows

Like Saturn, Uranus has rings—but they are faint, dark, and elusive. Discovered in 1977, the rings of Uranus are composed mostly of large, dark particles, likely made of rock and ice coated with organic compounds. Unlike Saturn’s bright, shimmering bands, Uranus’s rings are narrow and dim, casting ghostly arcs of shadow across the planet’s pale surface.

There are 13 known rings, each distinct in structure and composition. Some are thin, sharp-edged ribbons of dust, while others are diffuse and hazy. The outermost rings are surprisingly dynamic, containing clumps and waves that may be caused by tiny “shepherd moons” orbiting nearby.

These rings tell a story of collisions and gravity—a cosmic ballet of fragments caught in eternal orbit. They remind us that even in the darkest, most distant reaches of the solar system, beauty finds a way to endure.

The Family of Moons

Uranus is orbited by 27 known moons, each named not after mythological gods, but after characters from the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope. Among them are Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon—each a world of mystery, frozen in the dim light of their tilted master.

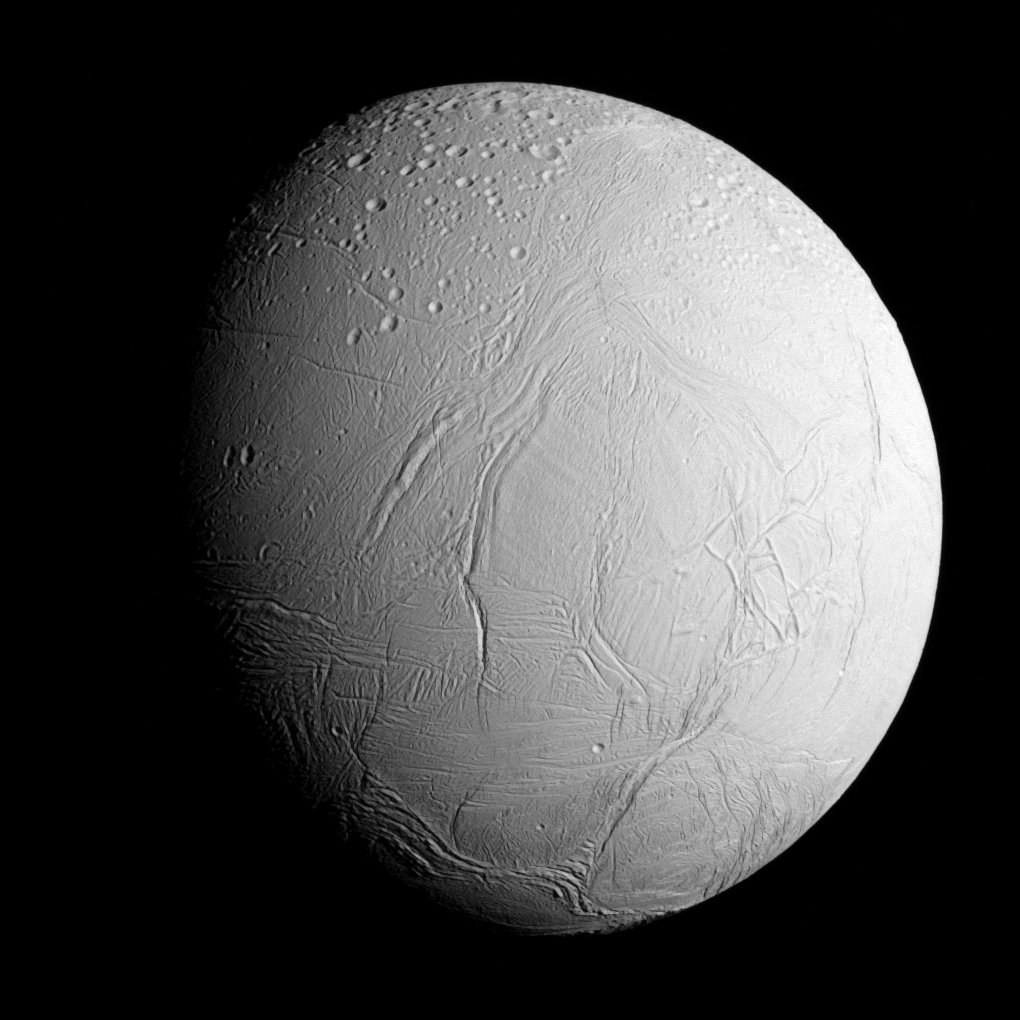

Miranda, the innermost of the large moons, is one of the most peculiar objects in the solar system. When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986, it revealed Miranda’s tortured surface—massive cliffs, ridges, and patchwork terrain that looks like a world shattered and stitched back together. Some of its cliffs rise higher than Mount Everest, towering over a world no larger than Earth’s smallest moon.

Titania and Oberon, larger and more distant, are icy realms with ancient craters and dark plains. Ariel, meanwhile, appears smoother, hinting that internal activity may once have reshaped its surface. These moons, though frozen, bear the scars of a violent past—evidence of tectonic shifts, impacts, and perhaps even ancient oceans beneath their icy crusts.

Each moon orbits along the planet’s equatorial plane, which means that as Uranus rolls on its side, so do its moons. From afar, they appear to circle the planet in a great tilted wheel, moving through a sky unlike any other in the solar system.

Voyager 2: The Lone Visitor

Only one spacecraft has ever visited Uranus—NASA’s Voyager 2. In January 1986, after a decade-long journey through space, Voyager 2 made its historic flyby, coming within 81,500 kilometers of the planet’s cloud tops.

During that brief encounter, the spacecraft sent back the first close-up images of Uranus, revealing its pale blue atmosphere, faint rings, and moons in stunning detail. For the first time, humanity saw the frozen landscapes of Miranda, Titania, and Ariel, and glimpsed the icy serenity of a world beyond imagination.

Voyager 2’s instruments measured the planet’s temperature, magnetic field, and composition, unlocking secrets that still shape our understanding of ice giants today. Yet, for all it revealed, it also left behind an ocean of unanswered questions.

Since that fleeting visit, no spacecraft has returned. Uranus remains a distant enigma, waiting patiently in the dark for the next messenger from Earth to arrive.

The Mystery of the Missing Heat

Uranus defies expectations in many ways, but perhaps the most perplexing is its lack of internal heat. Every other giant planet radiates more heat than it receives from the Sun, powered by residual energy from its formation or slow gravitational contraction. But Uranus radiates almost nothing extra.

It’s as though the planet’s heart has gone cold.

Scientists speculate that the ancient collision that tipped Uranus over may also have scattered its internal layers, preventing heat from rising outward. Another theory suggests that the core may be insulated by a thick, non-convective layer that traps warmth deep within.

Whatever the reason, Uranus’s frozen silence adds to its air of melancholy—a world that seems to have suffered some ancient trauma and never fully recovered.

The Long Seasons of Light and Shadow

Because of its extreme tilt, Uranus experiences seasons like no other planet. Each pole spends about 42 Earth years in continuous daylight, followed by 42 years of darkness. When the planet approaches its equinox, sunlight begins to reach the equator, and massive atmospheric changes seem to awaken storms that have slept for decades.

From a human perspective, the passage of time on Uranus would be surreal. A single day lasts 17 hours, yet a single year stretches across 84 Earth years. Imagine standing near one of its poles—watching the Sun rise once in your lifetime, then setting only as your world’s year drew to its slow close.

This rhythm of long light and longer shadow has shaped the planet’s weather, its atmosphere, and perhaps even its magnetic field. Uranus moves through time like a dream—slow, rhythmic, and eternal.

The Future of Exploration

Despite its beauty and strangeness, Uranus has been largely neglected since Voyager 2’s flyby. But that is beginning to change. Scientists now see Uranus as a key to understanding not only our solar system but countless exoplanets beyond it.

Many of the planets discovered orbiting other stars are “mini-Neptunes” or “ice giants,” similar in size and composition to Uranus. By studying this distant world up close, we could learn how these planets form, evolve, and maintain their atmospheres.

NASA has proposed a flagship mission to Uranus, possibly launching in the 2030s, which would arrive decades later. Equipped with modern instruments, it could orbit the planet, drop probes into its atmosphere, and study its moons in detail. This mission could finally reveal the secrets of the sideways giant—its hidden heat, its magnetic mysteries, and the stories written in its frozen clouds.

The Heart of the Ice Giant

What lies deep within Uranus remains one of astronomy’s most haunting questions. Beneath its cold clouds, immense pressures compress gases and ices into exotic forms—supercritical fluids, crystalline structures, and perhaps even oceans of liquid diamond.

Some scientists believe that deep inside Uranus and Neptune, carbon atoms could be squeezed into diamond rain, falling through layers of ammonia and methane in glittering cascades. If true, Uranus may be a planet of diamonds—its heart shimmering in darkness, unseen and unreachable.

This possibility captures the imagination like few others: a world of unimaginable cold, yet raining jewels in the eternal night. It is both science and poetry combined, a reminder that nature’s creativity knows no bounds.

Uranus as a Cosmic Time Capsule

Uranus is not just strange—it’s ancient. It preserves conditions from the early solar system, frozen snapshots of chemistry and formation processes that shaped all the outer planets. Unlike Jupiter or Saturn, which grew massive enough to become miniature suns of hydrogen and helium, Uranus never accumulated that much gas. It is, in many ways, a fossil of planetary formation—a reminder of how fragile the line is between a gas giant and an ice giant.

By studying Uranus, scientists can glimpse the processes that formed not only our own solar system but planetary systems across the galaxy. Each measurement, each image, each discovery draws us closer to understanding where we came from and how rare—or common—our world may be.

The Poetry of Isolation

There is a strange melancholy to Uranus. It is not the fiery heart of a star or the colorful tempest of Jupiter. It is a quiet world, distant and cold, whispering through the void. Its tilted spin and dim light make it seem like a planet caught mid-fall, forever rolling in silence.

Yet in that stillness lies grace. Uranus embodies the mystery and beauty of the unknown—the quiet majesty of a world that keeps its secrets not out of malice, but out of time’s slow patience.

Looking upon Uranus is like gazing into the cosmos itself: cold, beautiful, and full of unanswered questions. It reminds us that not all wonders are loud or bright—some simply drift, serene and waiting, until we dare to look deeper.

The Legacy of a Sideways World

Uranus challenges our assumptions about what a planet should be. It spins sideways, hides its storms, and whispers its heat instead of roaring it. It is a paradox—a giant wrapped in silence, a planet of ice that may rain diamonds, a world where day and night can last for decades.

It reminds us that the universe delights in the unexpected. That even in the farthest, coldest reaches, there are stories worth hearing.

As future generations of explorers turn their telescopes and spacecraft toward this pale blue enigma, Uranus will once again reveal its secrets, one by one. Perhaps we will learn why it tilts, why it chills, and what hidden wonders lie beneath its icy clouds.

The Endless Mystery

For now, Uranus remains a world seen only briefly, its mysteries still intact. It circles the Sun slowly and silently, a turquoise gem gliding through the darkness. Its faint rings, its frozen moons, its tilted axis—all remind us that beauty in the universe often hides in strangeness.

And so Uranus waits—a sideways sentinel at the edge of the known, guarding the secrets of creation beneath layers of ice and shadow.

We may not yet understand it fully, but we are drawn to it all the same. Because Uranus, like all the great mysteries of the cosmos, speaks to something deeper than curiosity. It speaks to our longing to know, to reach, and to wonder.

It tells us that even in the coldest darkness, there is still light.

And somewhere, far beyond the warmth of the Sun, that light glows faint and blue—a reminder that mystery, beauty, and truth are never truly separate. They simply wait, spinning sideways in the endless night, until we are ready to find them.