For millennia, humanity gazed at the night sky and wondered whether we were alone. The stars glittered like scattered jewels upon a velvet expanse, each one distant, mysterious, and—until recently—utterly unreachable. Philosophers speculated that other worlds might circle those distant suns, harboring beings and landscapes beyond imagination. Yet for all our dreams, the existence of such worlds remained purely hypothetical.

That changed in the late 20th century. With the development of precision instruments and space telescopes, humanity discovered that planets are not rare—they are everywhere. These distant worlds, orbiting stars beyond our Sun, are known as exoplanets. Their discovery has transformed our understanding of the universe, revealing a cosmos teeming with diversity and possibility.

The study of exoplanets is not just a branch of astronomy; it is a revolution in human thought. It forces us to confront the immensity of creation, the fragility of our own world, and the tantalizing question of whether life—perhaps intelligent life—exists elsewhere. Each new exoplanet is a revelation, a piece of a vast cosmic puzzle that redefines what it means to be part of the universe.

The Dream of Other Worlds

The idea of worlds beyond our own is ancient. As early as the 4th century BCE, the Greek philosopher Epicurus suggested that “there are infinite worlds both like and unlike this world of ours.” Centuries later, Giordano Bruno, a Renaissance thinker, proclaimed that every star was a sun with its own planets and perhaps life. His vision was deemed heretical at the time, but today it reads like prophecy.

For most of human history, the stars appeared fixed and immutable. Even after Galileo’s telescope revealed moons around Jupiter, the idea of other planetary systems remained speculative. There was no way to detect them. A planet orbiting another star would be drowned in its star’s blinding light, invisible even through the most powerful telescopes of the early modern era.

Still, the dream endured. In literature, imagination filled the gaps science could not. From Kepler’s Somnium to the worlds of science fiction, writers and thinkers built entire universes populated with alien skies and distant suns. Humanity’s curiosity was not idle; it was an expression of a deeper truth—the yearning to know whether we are unique or merely one example of a universal story.

The Birth of a New Science

The discovery of the first confirmed exoplanet around a Sun-like star in 1995 marked a turning point in astronomy. Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz announced that they had detected a planet orbiting the star 51 Pegasi, about 50 light-years away. The planet, known as 51 Pegasi b, defied expectations. It was a massive gas giant, half the mass of Jupiter, but orbiting extremely close to its star—so close that its “year” lasted just four Earth days.

This “hot Jupiter” was unlike anything in our Solar System. Its discovery shattered long-held assumptions about planetary formation and forced scientists to reconsider how diverse planetary systems could be. Within a few years, more such planets were found, revealing that nature’s creativity far exceeded our imaginations.

Today, exoplanet discovery has become one of the most vibrant fields in astronomy. Thousands of planets have been confirmed, and new ones are found almost weekly. We now know that planets outnumber stars in the Milky Way—there may be more than a trillion of them. What began as speculation has become a vast new frontier of exploration.

How We Find Invisible Worlds

Detecting an exoplanet is a remarkable feat of inference. We cannot yet see most of them directly; instead, astronomers detect their presence through subtle effects on their parent stars. Each method provides a unique window into the hidden architecture of distant solar systems.

The first and most enduring method is the radial velocity technique. As a planet orbits its star, it exerts a tiny gravitational tug, causing the star to wobble slightly. This motion shifts the star’s light spectrum through the Doppler effect—red when moving away, blue when moving toward us. By measuring these minute changes, astronomers can infer the planet’s presence, its mass, and its orbital period.

The second breakthrough came with the transit method, used to stunning effect by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. When a planet passes in front of its star, it blocks a tiny fraction of starlight, creating a periodic dimming. By observing these dips in brightness, astronomers can determine a planet’s size and even glean information about its atmosphere. The Kepler mission alone discovered over 2,600 exoplanets, revealing an astonishing variety of worlds.

Other methods add nuance and precision. Gravitational microlensing detects planets when their gravity briefly magnifies the light of a background star. Direct imaging, though challenging, has captured actual pictures of exoplanets around nearby stars. Astrometry—measuring a star’s position with exquisite precision—offers yet another path to discovery. Together, these techniques form a cosmic symphony of data, transforming specks of light into full-fledged worlds.

The Diversity of Alien Worlds

If there is one lesson from exoplanet science, it is that nature defies our expectations. The planets of our Solar System once seemed like a template, but exoplanets have shown that planetary systems come in astonishingly diverse forms.

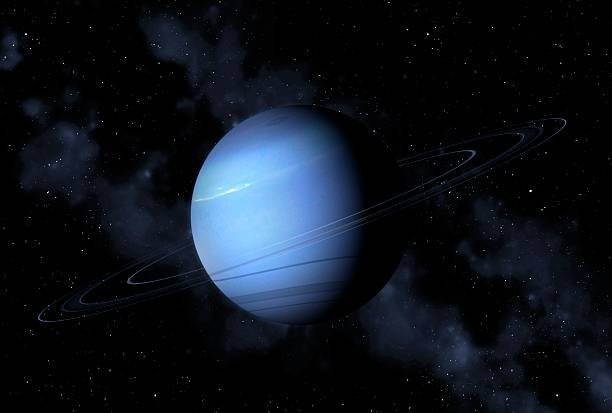

There are hot Jupiters—gas giants orbiting so close to their stars that their atmospheres boil away in fierce stellar winds. There are super-Earths, rocky planets larger than our own but smaller than Neptune, possibly with vast oceans or thick atmospheres. There are mini-Neptunes, shrouded in hydrogen and helium, and rogue planets that wander the galaxy unbound to any star, ejected from their birth systems in cosmic chaos.

Some planets orbit two suns, like the fictional Tatooine of Star Wars. Others circle dying stars, pulsars, or even black holes. Some have orbits so elliptical that their climates swing from hellish heat to frozen desolation. The sheer variety of these worlds suggests that the universe’s creativity is boundless.

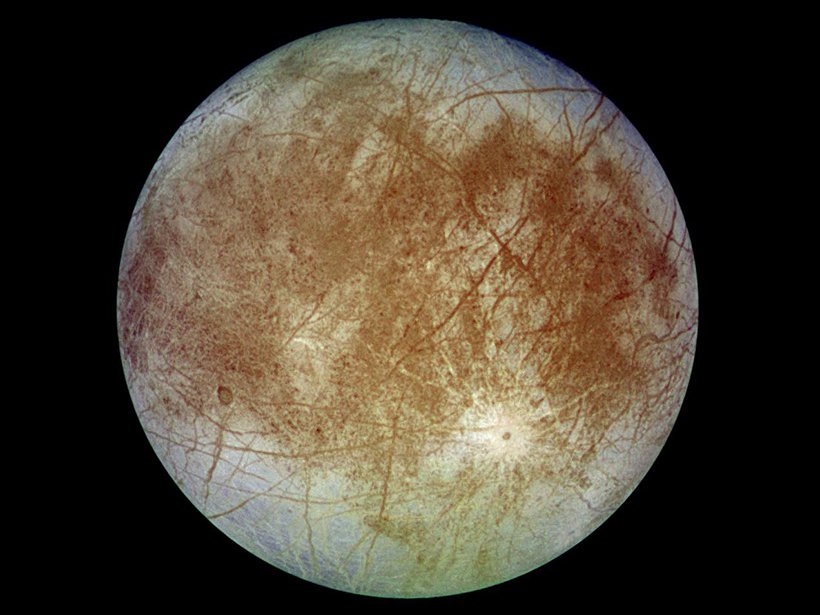

Perhaps the most intriguing are those that reside in the habitable zone—the region around a star where temperatures might allow liquid water to exist. Water, as far as we know, is the essence of life. Planets in this zone are prime candidates in the search for living systems beyond Earth. Yet even within this “Goldilocks zone,” conditions vary widely. A planet’s atmosphere, magnetic field, and composition all play crucial roles in determining whether it could support life.

The Kepler Revolution

NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, launched in 2009, changed everything. For nine years, Kepler stared at a patch of sky in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra, observing over 150,000 stars simultaneously. Its mission was simple yet profound: to measure tiny dips in brightness that indicated transiting planets.

The results were astonishing. Kepler revealed that planets are not rare exceptions but the rule. It found systems with tightly packed orbits, planets orbiting binary stars, and even Earth-sized worlds in habitable zones. Before Kepler, we knew of a few hundred exoplanets. By the end of its mission, we knew of thousands—and the implication was staggering: nearly every star in the galaxy likely hosts at least one planet.

Kepler’s discoveries transformed statistics into a revelation. For every grain of sand on Earth’s beaches, there are thousands of planets in the cosmos. The question was no longer whether other worlds exist, but what they are like—and whether any resemble our own.

The Search for Earth 2.0

Among all exoplanets, the most coveted are those that might be Earth-like—rocky, temperate, and capable of supporting life. Finding such worlds is immensely difficult, for their dim signatures are easily drowned by the brilliance of their stars. Yet progress has been relentless.

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched in 2018, continues Kepler’s legacy with a broader view of the sky. It has already found thousands of potential exoplanets, including several near Earth-like candidates. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in 2021, has brought a new era of precision. With its infrared vision, it can probe the atmospheres of exoplanets, analyzing starlight that passes through their gaseous envelopes during transit.

By studying these spectra, astronomers can detect molecules such as water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, and oxygen—the chemical fingerprints of potential life. Already, JWST has detected carbon-based molecules and signs of complex chemistry in distant atmospheres. These observations do not yet confirm life, but they hint at worlds with dynamic, active environments.

The search for “Earth 2.0” is not just a technical quest but an existential one. If we find a truly Earth-like planet—a blue world orbiting a sunlike star—it will challenge the uniqueness of our home and expand the boundaries of what we call life’s domain.

The Music of the Stars

Exoplanet science is as much about stars as it is about planets. Stars are the canvases upon which planetary systems are painted, and their properties shape the worlds that form around them. Red dwarfs, the smallest and most common type of star, host many of the known exoplanets. These stars are cooler and dimmer than the Sun, so their habitable zones lie much closer in.

Planets around red dwarfs often face extreme conditions. Because they orbit so near their stars, they may be tidally locked, with one side in perpetual daylight and the other in endless night. Stellar flares can strip away atmospheres or bathe their surfaces in radiation. Yet some may possess thick atmospheres or magnetic fields that protect them, creating oases of potential habitability in otherwise hostile systems.

Larger, hotter stars may host planets farther out, but their lifespans are short—too brief for life as we know it to develop. Thus, the sweet spot for life-bearing worlds may lie around stars similar to or smaller than our Sun, stable for billions of years and gentle enough to nurture the slow evolution of complexity.

Worlds of Fire and Ice

Every exoplanet discovered reveals a new facet of cosmic creativity. Some are infernos—like KELT-9b, a planet so hot that its atmosphere vaporizes metals. Others are frozen giants, orbiting far from dim stars in perpetual twilight. Some are “water worlds,” potentially covered entirely by deep oceans, while others may have diamond cores or silicate rain.

One of the most extraordinary systems is TRAPPIST-1, a red dwarf about 40 light-years away with seven Earth-sized planets. Three of them lie within the habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water. This system, discovered in 2017, has become a focal point for studying potentially life-supporting environments. The TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit so close to their star that all seven would fit within Mercury’s orbit around the Sun, yet their delicate gravitational dance remains stable—a cosmic choreography both fragile and enduring.

Each world, no matter how alien, offers clues about how planets form and evolve. Some systems challenge our theories entirely, showing architectures so different from our own that they demand new models of planetary physics. Exoplanets, in all their diversity, are reshaping our understanding of what a “planet” even means.

The Chemical Clues of Life

Detecting life beyond Earth—biosignatures—is the holy grail of exoplanet research. But what counts as evidence? Life, as we know it, alters its environment. On Earth, photosynthesis fills the air with oxygen, while respiration produces carbon dioxide and methane. A similar combination of gases on another planet could hint at biology.

Telescopes like JWST and the upcoming Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) aim to detect these chemical fingerprints. When starlight filters through a planet’s atmosphere during transit, certain wavelengths are absorbed by specific molecules. By analyzing these patterns, scientists can determine what gases are present—and whether they exist in combinations unlikely to occur without life.

However, interpreting these signs is fraught with complexity. Geological processes, photochemistry, and even stellar activity can mimic biosignatures. Thus, the search for life requires not just observation but context: understanding the planet’s temperature, pressure, and history. The goal is not simply to find molecules, but to understand the living systems—or nonliving processes—that created them.

The Cosmic Perspective

The discovery of exoplanets has changed our place in the cosmos. Once, Earth seemed singular—a lone oasis amid the vast emptiness. Now we know that worlds are common. There may be billions of Earth-sized planets in our galaxy alone. This realization humbles us and expands our imagination.

Each new exoplanet is a mirror, reflecting a different possibility of existence. Some worlds may resemble early Earth, still molten and stormy. Others may echo its distant future, scorched or frozen as their stars evolve. In studying them, we glimpse not only alien landscapes but also our planet’s own destiny.

The search for exoplanets is also a search for meaning. It connects science with philosophy, curiosity with awe. When we look at a star and imagine its unseen planets, we participate in the oldest human tradition—the desire to know what lies beyond the horizon.

The Future of Exploration

The next generation of telescopes promises to turn imagination into observation. The James Webb Space Telescope is already peering into exoplanetary atmospheres. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, set to launch later this decade, will conduct wide-field surveys that may detect thousands more. The European Space Agency’s PLATO mission will focus on finding Earth-like planets around Sun-like stars.

Even more ambitious are the concepts for direct imaging missions—space telescopes equipped with coronagraphs or starshades to block starlight and reveal faint planetary reflections. These instruments could, for the first time, take true portraits of other Earths, perhaps showing oceans, continents, or clouds.

Future explorers may not only observe but also visit. Robotic probes propelled by laser sails or plasma engines could one day reach nearby systems such as Alpha Centauri within decades. The dream of interstellar travel, once confined to science fiction, is slowly entering the realm of engineering.

The Philosophy of Other Worlds

The existence of exoplanets reshapes humanity’s philosophical landscape. If there are billions of planets, many similar to Earth, then life may not be an isolated phenomenon. Perhaps the universe is not silent but filled with the whisper of countless living worlds.

This idea does not diminish Earth’s significance—it magnifies it. Our planet becomes part of a cosmic tapestry of life, a single verse in an unending symphony. The search for other worlds is, in the end, a reflection of our search for ourselves. We look outward not merely to find others, but to understand our place in the vast, unfolding story of creation.

The Endless Horizon

The discovery of exoplanets marks a new age of exploration—not across oceans or continents, but across light-years. It is a journey of the mind and spirit, expanding our perception of what is possible. Each distant world is a reminder that the universe is not static but alive with creation, a dynamic system where stars and planets dance to the rhythm of gravity and time.

As our instruments grow sharper and our reach extends farther, we may one day find a planet that mirrors our own—a blue sphere orbiting a golden sun, with oceans that glimmer under alien skies. Perhaps, upon that world, beings of another kind gaze upward at their stars, wondering if they too are alone.

In that moment, the circle will close. The universe will no longer be a silent expanse but a dialogue between worlds, between minds separated by light-years yet united by curiosity.

The discovery of exoplanets reminds us that wonder is endless. Beyond every horizon lies another, beyond every discovery another mystery. We stand at the dawn of a cosmic awakening, where each new world is not just a point of light, but a story waiting to be told.

In the boundless night, beneath the infinite stars, we have found companions—distant, silent, and shining. They are the echoes of possibility, the promise that we are part of something far greater than ourselves. The universe, once a mystery, is now a multitude—and our small blue planet, once thought unique, is merely one voice among countless worlds in the eternal song of the cosmos.