There are few questions more profound than this: What existed before the Big Bang? It is a question that challenges the limits of human understanding, the boundaries of physics, and even the nature of existence itself. It invites us to peer beyond the curtain of time, to imagine a “before” where perhaps time itself did not exist. It is not just a question about science, but about meaning, origins, and the very fabric of reality.

For most of human history, people have wondered how everything began—how the universe, with its galaxies, stars, and living beings, came into being. Ancient mythologies offered their own explanations: creation from chaos, emergence from cosmic eggs, or birth from divine thought. But in the twentieth century, physics gave us something even more astonishing—a scientific story of creation that begins not with gods or miracles, but with an explosion of space and time itself.

The Big Bang theory describes the universe’s earliest moments, when all matter, energy, space, and time expanded from an unimaginably dense and hot state roughly 13.8 billion years ago. It is not merely an explosion in space—it is an expansion of space. Galaxies are not flying outward into empty void; rather, the void itself is stretching, carrying galaxies with it.

Yet this raises a haunting question: if space and time themselves began with the Big Bang, then what does it even mean to speak of “before”? Is it a meaningless question, like asking what lies north of the North Pole? Or could there have been something—some primordial reality, a hidden realm—that gave rise to the cosmos we inhabit today?

Modern physics has not yet provided a definitive answer, but it has given us several tantalizing possibilities. To explore them is to walk at the edge of knowledge, where science meets philosophy and imagination brushes against eternity.

The Big Bang: A Beginning of Everything

To understand what might have come before the Big Bang, we must first understand what the Big Bang actually was—and what it was not.

The term “Big Bang” can be misleading. It evokes an image of an explosion erupting into empty space. But that picture is wrong. The Big Bang was not an explosion in space; it was an expansion of space itself. There was no “outside” into which the universe expanded. All of space, all directions, all points of reality were compressed together, and the expansion happened everywhere at once.

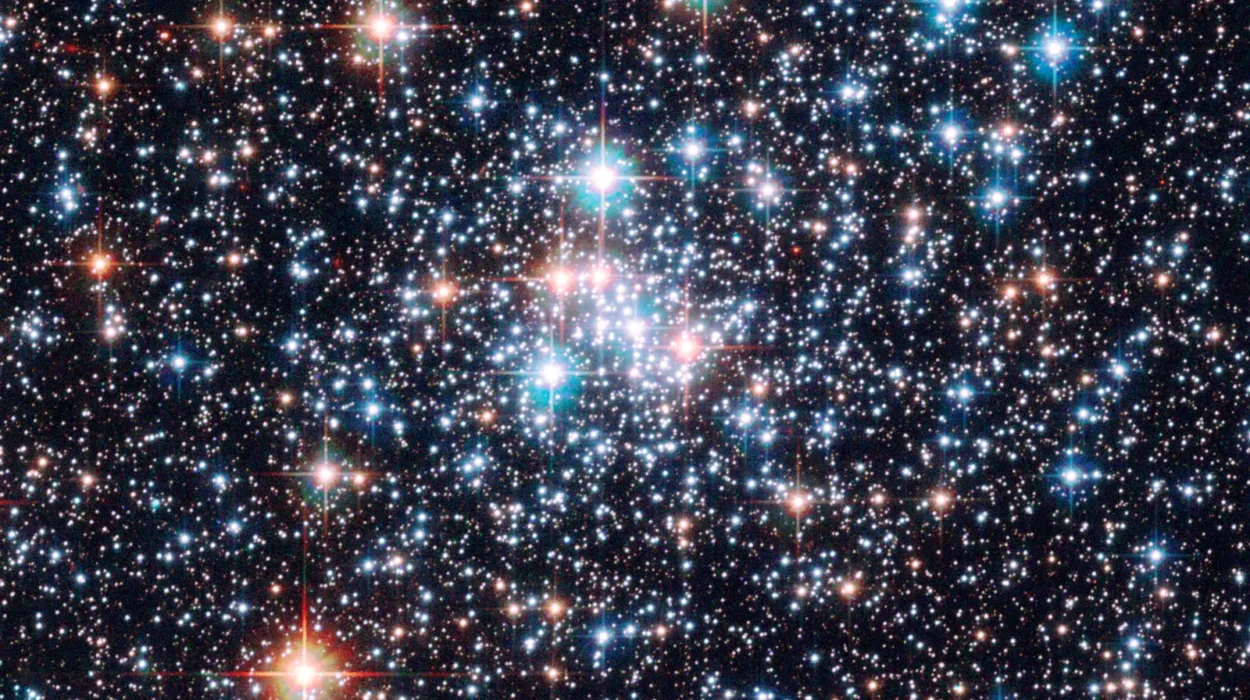

According to the standard cosmological model, the universe began in a state of extreme density and temperature. In its earliest moments, it was filled with a hot, opaque plasma of particles and radiation. As it expanded, it cooled, allowing atoms to form, light to travel freely, and structures like galaxies and stars to emerge. The cosmic microwave background—an afterglow of the Big Bang—still fills the universe today, a faint whisper from that ancient fireball.

But if the Big Bang marks the beginning of space and time, it also marks the boundary of our knowledge. Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which describes gravity and the large-scale structure of the cosmos, breaks down at the singularity—the point where density and curvature become infinite. To understand what happened at or before that point, we need a theory that unites relativity with quantum mechanics—a theory of quantum gravity.

Without such a theory, the question “what existed before the Big Bang?” remains unresolved. But that has not stopped scientists and philosophers from exploring what the answers might be.

The Limits of Time and the Illusion of “Before”

One of the first lessons that modern cosmology teaches is that time itself is not absolute. Time is not a river flowing independently of the universe; it is a property of space-time, shaped by gravity and energy. When we say that time “began” at the Big Bang, we mean that the concept of time—at least as we understand it—has no meaning before that moment.

Stephen Hawking once illustrated this idea with a simple analogy. Asking what came before the Big Bang, he said, is like asking what is north of the North Pole. There is no “north” beyond the pole because it is the boundary of that coordinate system. Similarly, if time began at the Big Bang, then “before” may be meaningless, because there was no time in which “before” could occur.

In this view, the Big Bang was not an explosion happening at a moment in time—it was the moment when time itself began. The universe did not emerge into existence from something else; rather, existence itself emerged from the absence of time. The Big Bang, then, represents not just a beginning of matter and energy, but the beginning of temporality.

And yet, this explanation, elegant though it is, leaves many unsatisfied. It feels incomplete. For if time had a beginning, what determined that it should begin at all? What set the stage for existence to arise from nonexistence? Physics may not easily answer that—but it can explore what might lie beyond the reach of classical time.

Quantum Beginnings: When Nothing Fluctuates

In the quantum world, the concept of “nothing” is not as simple as it seems. According to quantum field theory, even the vacuum—the emptiest possible state—is not truly empty. It seethes with virtual particles, fleeting fluctuations that pop in and out of existence. These quantum fluctuations can produce energy and even entire regions of space-time under the right conditions.

This leads to a fascinating possibility: perhaps the universe did not emerge from nothing, but from a quantum vacuum—a primordial state with no matter or radiation, but with energy and potential.

Physicists like Edward Tryon and later Stephen Hawking suggested that the universe could be a kind of quantum fluctuation. In this picture, the universe “tunneled” into existence spontaneously, much as particles can appear in quantum experiments. Because the total energy of the universe might be zero—positive energy in matter and radiation balanced by negative gravitational energy—it could have arisen without violating conservation laws.

From this viewpoint, the Big Bang was not the beginning of existence but a transition—a quantum event in a preexisting vacuum, a fluctuation that expanded and cooled into the cosmos we know. This does not mean there was a “before” in the classical sense, but it does mean that something existed: a quantum field, a timeless sea of potential, from which universes can emerge.

Quantum cosmology extends this idea further through models like the Hartle-Hawking “no-boundary proposal,” which envisions the universe as finite but without edges or beginnings—like a sphere in time. According to this theory, the universe has no singular starting point; time gradually emerges from a timeless, quantum state. The question of “before” the Big Bang becomes unnecessary, because the universe has no boundary at which “before” could exist.

The Eternal Universe: Cycles of Creation and Destruction

While quantum models offer one path to understanding pre-Big Bang conditions, other theories suggest that the universe may be eternal—that the Big Bang was not the first beginning, but one of many cosmic transitions in an infinite cycle.

Cyclic or oscillating cosmologies propose that the universe undergoes endless phases of expansion and contraction. In these models, the Big Bang is simply the latest “bounce” in a series of cosmic rebirths. The idea dates back to early 20th-century cosmologists like Richard Tolman, who speculated that each universe might collapse into a “Big Crunch,” followed by another Big Bang.

Modern versions of cyclic cosmology have been developed in the context of string theory and quantum gravity. The ekpyrotic model, proposed by Paul Steinhardt and Neil Turok, envisions our universe as one of two three-dimensional “branes” (membranes) in a higher-dimensional space. When these branes collide, they release energy and trigger a Big Bang. After expanding, the branes drift apart, only to collide again in the far future. In this view, the universe has no true beginning—only an eternal sequence of cycles, each giving birth to new cosmoses.

Such models elegantly avoid the problem of a singularity by replacing it with a “bounce.” Near the point where general relativity breaks down, quantum gravity effects take over, reversing contraction into expansion. The universe never reaches infinite density; it simply transitions from one phase to another.

If true, this would mean that the Big Bang was not the first act of creation, but merely the latest note in an endless cosmic symphony. The universe, far from being a one-time miracle, could be eternal—reborn again and again through cycles of death and renewal.

The Multiverse: Infinite Realities Beyond Our Own

Another line of thought suggests that our universe may be just one among countless others—a single bubble in an infinite cosmic sea. This concept, known as the multiverse, arises naturally from several branches of modern physics, including inflationary cosmology and string theory.

According to the theory of cosmic inflation, proposed by Alan Guth in the 1980s, the universe underwent an exponential expansion in its first fraction of a second. Inflation explains why the cosmos appears uniform on large scales and why space is nearly flat. But inflation may not have ended everywhere at once. In some regions, it could continue indefinitely, creating new “bubble universes” that expand and evolve independently.

In this picture, our Big Bang was the birth of one such bubble. Beyond our cosmic horizon lie countless others, each with its own laws of physics, dimensions, and constants. Some may resemble ours; others may be wildly different. The multiverse, if real, implies that creation is not a singular event but a perpetual process.

String theory, too, suggests the existence of multiple universes. It envisions a vast “landscape” of possible vacuum states, each corresponding to a different configuration of physical laws. Our universe might simply be one realization among trillions, selected by chance or by quantum fluctuation.

If the multiverse exists, then the question “what came before the Big Bang?” may be replaced by “which universe did ours emerge from?” Perhaps our Big Bang was the result of a collision between universes or a decay from a higher-dimensional state. In this vast cosmic hierarchy, beginnings may be relative, not absolute.

The Nature of Nothing

The notion of “nothingness” lies at the heart of the question. But what do we mean by “nothing”?

In everyday language, “nothing” implies the absence of everything—no matter, no energy, no space, no time. But physics shows that such absolute nothingness may not even be possible. Even the “vacuum” of space is filled with fields, fluctuations, and the potential for creation.

In quantum mechanics, “nothing” can be unstable. A vacuum can give rise to particles, energy, and even space-time itself. Thus, the universe could have emerged from “nothing” in a physical sense—if “nothing” means a quantum vacuum governed by laws of physics. But this still raises a deeper question: where did those laws come from? Why is there something rather than absolute nothingness?

Some philosophers and physicists argue that “nothing” is not a meaningful state. The laws of physics may not “exist” independently; they are descriptions of how reality behaves. If reality itself is necessary—if existence is the default—then perhaps there was never “nothing” at all.

Others, like cosmologist Lawrence Krauss, have argued that physics can indeed describe how a universe can emerge from “nothing,” but critics point out that Krauss’s “nothing” still contains quantum fields and physical laws. True philosophical nothingness—no laws, no potential, no existence—may be beyond comprehension, or perhaps an incoherent concept.

Time Before Time

What if “before” the Big Bang does not mean “earlier” in time, but something else entirely?

Some physicists have proposed that time itself may be emergent—a property that arises from deeper, timeless structures. In this view, the Big Bang marks not the start of time, but the transition from a timeless quantum state to a universe where time behaves as we experience it.

Carlo Rovelli, a pioneer of loop quantum gravity, suggests that time may not be fundamental. In his theory, space and time are woven from discrete “quanta” of geometry. Before the Big Bang, there may have been no flowing time, only a network of relationships—a pre-geometric state from which space-time emerged.

Similarly, Roger Penrose’s conformal cyclic cosmology posits that time extends infinitely in both directions but changes its meaning across aeons. In his model, the remote future of one universe, where all matter has decayed and only radiation remains, becomes indistinguishable from the Big Bang of the next. Time, in this vision, is circular—a cosmic loop with no beginning and no end.

These ideas challenge our deepest intuitions, for they suggest that time as we know it is not absolute but a phase—a quality that arises when certain physical conditions are met. If so, the Big Bang did not happen in time; time happened because of the Big Bang.

The Role of Observation and Consciousness

As physics delves into the origins of existence, some thinkers have wondered whether consciousness itself plays a role in the fabric of reality. Quantum mechanics famously reveals that observation affects outcomes—the act of measurement collapses probabilities into definite states. Could the universe itself, at its birth, have been shaped by a kind of cosmic observation?

This idea is speculative, but it raises fascinating possibilities. If quantum laws govern the universe at its earliest moments, and if observation defines reality within those laws, then perhaps consciousness—or some proto-form of information—has always been intertwined with existence.

Some interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the participatory anthropic principle suggested by physicist John Archibald Wheeler, propose that observers are essential to the universe’s existence. The universe, in a sense, brings itself into being through observation—a self-aware cosmos.

While this notion verges on philosophy, it reminds us that understanding the universe’s beginning may require more than equations. It may demand reflection on the nature of reality itself—what it means to exist, to observe, to know.

Beyond the Horizon of Knowledge

Despite all our theories—quantum fluctuations, eternal inflation, cyclic universes, and multiverses—the truth is that we do not yet know what, if anything, existed before the Big Bang. Each hypothesis pushes the boundary of understanding further, but none can yet be confirmed. The singularity remains a veil—an event horizon not of black holes, but of knowledge itself.

Yet this mystery is not a failure of science; it is its greatest triumph. The fact that we can even ask such questions, grounded in evidence and mathematics, is a testament to the human mind’s reach. The universe has given rise to beings capable of reflecting on its own birth—a cosmic circle of awareness.

In the coming decades, new discoveries may illuminate the darkness before time. Observations of cosmic background radiation, gravitational waves, or the earliest galaxies may reveal traces of pre-Big Bang physics. Quantum gravity, if fully understood, may show how space and time emerge from deeper principles. And perhaps one day, the question “what came before the Big Bang?” will be replaced with a deeper one: “why does existence exist at all?”

The Meaning of the Beginning

Ultimately, the mystery of what came before the Big Bang is not only a scientific question but a philosophical one. It forces us to confront the limits of language and imagination, to ask what “nothing” and “something” even mean.

Maybe there was never “nothing.” Maybe the universe, in some form, is eternal—changing, cycling, evolving through phases we cannot yet comprehend. Or maybe, in the deepest sense, there was truly nothing—and from that nothing, existence arose spontaneously, a self-generating act of creation.

Whatever the truth, the search itself is sacred. It is the story of consciousness striving to understand its origin, of the universe asking about itself through us.

The Big Bang may have been the beginning of time, but the quest to understand it is timeless. Each new theory, each observation, brings us closer to the moment when physics, philosophy, and poetry converge—when we can glimpse, if only faintly, what lay beyond the dawn of everything.

The Eternal Mystery

Perhaps there was no “before,” no moment of creation, no cosmic architect. Or perhaps there was a realm beyond comprehension, a quantum sea from which universes are born like waves rising from an infinite ocean.

Whether the universe began from absolute nothing or from something subtler—a field, a fluctuation, a timeless state—it remains an act of unimaginable wonder. Every atom in our bodies, every star in the sky, every breath we take, originates from that ancient moment when existence itself began to unfold.

In the end, the question “what existed before the Big Bang?” may never be fully answered. But it continues to inspire us to look upward, to think deeply, and to feel awe at the fact that there is anything at all.

For perhaps the greatest mystery is not what came before the universe, but that there is a universe to ask about in the first place—and that, for a fleeting moment, a small species on a small planet can look into the night and wonder how it all began.