In the silent theaters of the cosmos, stars live and die like celestial actors performing their grand roles on the stage of time. Each star is born in a cloud of gas and dust, burning with brilliance for millions or even billions of years, only to face an inevitable fate written in the very physics that gives it life. Some die gracefully, leaving behind shimmering remnants known as neutron stars—tiny, dense jewels of matter that defy imagination. Others meet a darker destiny, collapsing into black holes, where even light cannot escape.

Why do some stars end as neutron stars while others vanish into the abyss of black holes? The answer lies in a delicate balance of mass, pressure, and gravity—a cosmic tug-of-war that determines the nature of a star’s final breath.

To understand this story, we must first journey into the heart of a star, to witness the processes that both sustain and destroy it.

The Life Within a Star

Every star, no matter how bright or faint, is a furnace powered by nuclear fusion. In its core, under immense pressure and temperature, hydrogen atoms merge to form helium, releasing a torrent of energy that radiates outward as light and heat. This energy pushes against the inward pull of gravity, creating a fragile equilibrium—a balance between collapse and explosion.

This equilibrium is the secret of a star’s stability. Gravity wants to crush the star into a singular point, while the outward pressure from fusion fights to keep it inflated. As long as there’s fuel to burn, this balance holds.

But fuel is not infinite. When a star begins to exhaust its hydrogen, it enters a phase of transformation. The core contracts under gravity’s relentless pull, while the outer layers expand, creating a red giant or, in the case of more massive stars, a red supergiant.

The fate of the star from this moment onward depends on one key factor—mass. Mass is destiny in the cosmos. It determines how fiercely a star burns, how long it lives, and what remains when it dies.

When Giants Begin to Die

For stars like our Sun, life ends in relative peace. After billions of years, the Sun will swell into a red giant, shed its outer layers in a glowing cloud of gas, and leave behind a small, dense remnant called a white dwarf—a cinder of carbon and oxygen slowly cooling in the dark.

But for stars that begin their lives with more than about eight times the mass of the Sun, the story turns tragic and violent. Their enormous gravity compresses the core to unimaginable densities, and their fusion furnaces burn through fuel at a furious rate.

When the core runs out of elements to fuse, something catastrophic happens: gravity wins.

The core collapses inward, and the outer layers of the star crash down upon it. Within a fraction of a second, this collapse triggers one of the most powerful explosions in the universe—a supernova. The blast releases more energy in a moment than the Sun will produce in its entire lifetime, scattering the elements forged in the star’s heart across space. These elements—carbon, oxygen, iron, gold—become the building blocks of future stars, planets, and even life itself.

Yet, amid the chaos of that explosion, the core faces its final judgment.

Will it resist the crush of gravity and stabilize as a neutron star?

Or will it collapse beyond redemption, becoming a black hole?

The answer depends entirely on how much mass remains after the supernova.

The Making of a Neutron Star

Imagine a star whose core, after the supernova, is about one and a half to three times the mass of the Sun. That may sound modest, but remember—this mass is squeezed into a sphere only about 20 kilometers across.

At this point, gravity is nearly unstoppable. The core collapses until protons and electrons are forced to merge, forming neutrons. This process releases a flood of neutrinos—ghostly particles that escape into space—and leaves behind a remnant made almost entirely of neutrons.

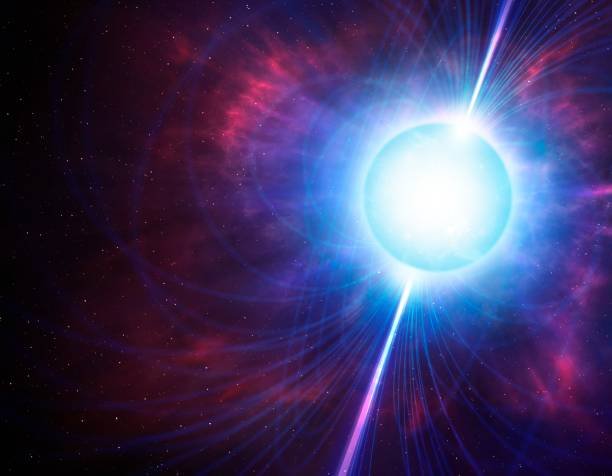

This object is a neutron star, one of the strangest entities in the cosmos.

A teaspoon of neutron star material would weigh about a billion tons on Earth. Its surface gravity is so intense that if you dropped a pebble from one meter above the surface, it would strike with the energy of a nuclear bomb.

And yet, despite this crushing density, neutron stars do not collapse completely. Why? Because they are supported by a quantum mechanical force known as neutron degeneracy pressure.

In quantum physics, no two identical particles—like neutrons—can occupy the same state at the same time. This rule creates a kind of resistance, a microscopic pressure that counters gravity’s pull. It’s as if the neutrons themselves are saying, “No closer.”

This resistance halts the collapse, creating a stable, ultra-dense sphere that spins rapidly and emits intense magnetic fields. Some neutron stars spin hundreds of times per second, beaming out radiation like a cosmic lighthouse. We call these pulsars.

But even this quantum resistance has its limits.

When Even Neutrons Surrender

If the core left behind after a supernova is more massive—perhaps more than three times the mass of the Sun—then gravity’s pull becomes irresistible. Not even neutron degeneracy pressure can stop the collapse.

At that critical threshold, the core implodes completely, crushing matter into an infinitesimal point of infinite density known as a singularity. Around this singularity forms an event horizon—the boundary beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape.

A black hole is born.

Unlike neutron stars, black holes are not made of matter in any traditional sense. They are regions of spacetime where gravity becomes absolute, where space is curved so steeply that all paths lead inward. The laws of physics as we know them break down at the singularity, leaving us with a mystery that even Einstein’s equations cannot fully solve.

In this way, the same cosmic forces that create neutron stars also give birth to black holes—it is mass, and only mass, that decides which path the dying star takes.

The Role of the Chandrasekhar and Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff Limits

To truly grasp why some stars end as neutron stars and others as black holes, we must understand the thresholds that nature enforces.

For white dwarfs, the limit is known as the Chandrasekhar limit—about 1.4 times the mass of the Sun. Beyond this, electron degeneracy pressure cannot resist gravity, and collapse continues until the star becomes a neutron star.

For neutron stars, there is a similar boundary called the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) limit, estimated to be around 2 to 3 solar masses. If a remnant’s mass exceeds this limit, even neutron degeneracy pressure fails, and a black hole forms.

Between these two limits lies a razor’s edge of cosmic balance—a narrow window where a star can survive as a neutron star but not yet fall into the abyss.

This boundary, uncertain and mysterious, represents one of the greatest dividing lines in nature—a point where matter itself decides whether it will remain visible or vanish from the universe forever.

The Strange Life of Neutron Stars

Neutron stars may be remnants, but they are anything but lifeless. They are among the most dynamic and exotic objects ever discovered. Some spin so fast they make a full rotation hundreds of times per second. These are millisecond pulsars, whose beams of radiation sweep across space like the ticking of a cosmic clock.

Others have magnetic fields a trillion times stronger than Earth’s—these are magnetars, and their magnetic power is so intense it can distort atoms and release bursts of X-rays that outshine entire galaxies for brief moments.

Over time, neutron stars cool, slow down, and fade, but their gravitational pull remains immense. If two neutron stars orbit each other, they can gradually spiral together, releasing gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime that were first detected by LIGO in 2015. When they finally collide, the result can be another explosion so powerful it forges gold, platinum, and other heavy elements, scattering them across the cosmos.

In fact, much of the gold in your jewelry and the iron in your blood was likely created in the collision of two neutron stars billions of years ago. You are, in a very literal sense, made of the ashes of dead stars.

The Darkness of Black Holes

Black holes, in contrast, are the universe’s great enigmas. They have no surface, no inside that we can see—only an event horizon, a one-way door through which information vanishes. To an outside observer, time appears to stop at the event horizon. To something falling in, time continues normally—until the singularity ends everything.

Despite their terrifying reputation, black holes are not cosmic vacuum cleaners sucking everything in. They obey the same gravitational laws as any other mass. You could orbit a black hole safely if you stayed far enough away—just as Earth orbits the Sun.

But approach too close, and escape becomes impossible.

When a massive star collapses into a black hole, it doesn’t simply disappear. The black hole retains its mass, spin, and electric charge. In a sense, it becomes a pure gravitational imprint, a record of what once was—a shadow of matter itself.

Over cosmic timescales, black holes may not even be eternal. According to Stephen Hawking’s theory of Hawking radiation, black holes slowly evaporate, emitting faint radiation as quantum effects near the event horizon allow particles to escape.

Given enough time—far more than the current age of the universe—even the largest black holes will eventually fade into nothingness, returning their energy to the void.

The Fine Line Between Light and Darkness

The difference between a neutron star and a black hole is measured in margins so narrow that they seem almost poetic. A fraction of a solar mass determines whether a star’s corpse will remain visible, spinning and singing across the cosmos, or vanish forever behind a veil of darkness.

Imagine two dying stars, nearly identical in mass. One sheds slightly more of its outer layers during the supernova, leaving behind a core just under the TOV limit. It becomes a neutron star—a visible remnant of cosmic resilience.

The other retains slightly more mass. That tiny difference pushes its core past the threshold, where gravity conquers every opposing force. It collapses beyond all recognition, leaving behind a black hole.

From the outside, these two fates could not be more different—one emits light and energy, the other swallows them whole. Yet they are born of the same process, the same death, the same laws of nature. In this way, the line between light and darkness in the cosmos is not a boundary—it is a whisper.

Supernovae: The Cosmic Rebirth

The death of massive stars is not just an end; it is also a beginning. Supernovae seed the universe with elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, enriching the interstellar medium. The carbon in your cells, the calcium in your bones, the iron in your blood—all were forged in these explosions.

Every star that dies contributes to the cycle of creation. The debris from one generation of stars becomes the raw material for the next. In this endless process of death and rebirth, neutron stars and black holes serve as silent witnesses—monuments to the creative and destructive power of gravity.

When Stars Collide

When two neutron stars or a neutron star and a black hole meet, the results are spectacular. Their collision can warp spacetime itself, producing gravitational waves that travel across the universe. In 2017, astronomers detected such a merger for the first time and observed light from the event—a “kilonova”—that confirmed heavy elements were created in the blast.

These cosmic collisions are not rare curiosities; they are essential to the chemistry of existence. Without them, the universe would be missing many of the elements that make planets and life possible.

In this sense, even the darkest objects—black holes—play a role in creation. Their gravity shapes galaxies, stirs matter, and drives cosmic evolution. Darkness and light are not enemies but partners in the universe’s grand design.

The Human Connection to Stellar Death

It is humbling to realize that our own existence depends on the deaths of stars. The atoms in our bodies were once part of ancient suns that lived, burned, and exploded long before Earth was born.

When you look up at the night sky, every point of light you see is not just a star—it is a story of physics, of creation and destruction, of balance and collapse. And somewhere out there, unseen, are the remnants of those that came before—neutron stars spinning silently, black holes bending the fabric of space itself.

Their existence reminds us that even in death, there is beauty. The universe recycles its own bones to create new worlds, new light, and new beginnings.

The Frontier of Understanding

Despite decades of study, the transition from neutron stars to black holes remains a frontier of mystery. Astronomers are still uncertain exactly where the dividing line lies. New discoveries, such as “mass-gap” objects that appear to be too heavy to be neutron stars yet too light to be black holes, are challenging our understanding of stellar death.

Future observatories, both on Earth and in space, will continue to probe these mysteries. Gravitational wave detectors will capture more stellar collisions, while X-ray telescopes will peer into the hearts of galaxies to study how these remnants shape the cosmos.

Each observation brings us closer to answering not just the question of how stars die, but the deeper question of how matter, energy, and gravity dance together to create the universe we see.

The Eternal Balance

In the grand story of the cosmos, stars live, die, and transform according to rules that are both simple and profound. The forces that guide their fates are the same that shape galaxies and govern the motion of planets.

Neutron stars and black holes are not opposites—they are two expressions of the same truth: that gravity, the most fundamental of all forces, is both creator and destroyer. It builds stars from dust and returns them to dust. It gives light and takes it away.

Every black hole was once a shining star. Every neutron star carries the memory of its former brilliance. Their silence is not emptiness—it is the echo of a light that once was, and perhaps, in some form, still is.

The Universe’s Final Symphony

If you could listen to the universe, you would hear the music of its stars—the low hum of gravitational waves, the ticking pulse of neutron stars, the silent rhythm of black holes merging in distant galaxies. Each note is a reminder of the life and death of suns, of the endless transformation of matter into energy and back again.

The story of why some stars become neutron stars while others become black holes is, ultimately, the story of balance—the eternal dance between pressure and gravity, creation and collapse, visibility and mystery.

And somewhere in that dance lies the most profound truth of all: that even in the deepest darkness, the universe is still singing.

It sings in the light of stars and the shadow of black holes, in the atoms of your blood and the silence of space. It sings the same song it has sung for 13.8 billion years—a song of energy becoming matter, of death giving birth to life, and of gravity writing poetry in the fabric of spacetime.

That is why some stars die into light, and others into darkness.

Because in the cosmos, as in all things, both are necessary for the music to continue.