More than three millennia ago, in the searing heat of the Bronze Age Nile Valley, women of Nubia balanced not only water jars and bundles of firewood on their heads—they carried history, resilience, and survival. Though their lives were unwritten, their bones have now begun to speak. A groundbreaking interdisciplinary study by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) has uncovered physical evidence that Nubian women developed skeletal adaptations from a life of bearing heavy loads on their heads. These transformations in bone structure, invisible to ancient scribes and largely ignored by modern historians, offer a powerful counter-narrative to the male-dominated depictions of prehistoric labor.

In what is now northern Sudan, the Kerma culture thrived between 2500 and 1500 BCE. While most historical attention has been lavished upon its rival to the north—ancient Egypt—Kerma was no peripheral backwater. It was a formidable kingdom in its own right, with trade networks, monumental architecture, and a distinct cultural identity. Yet, even in this rich archaeological landscape, the daily lives of women have often been obscured. Until now.

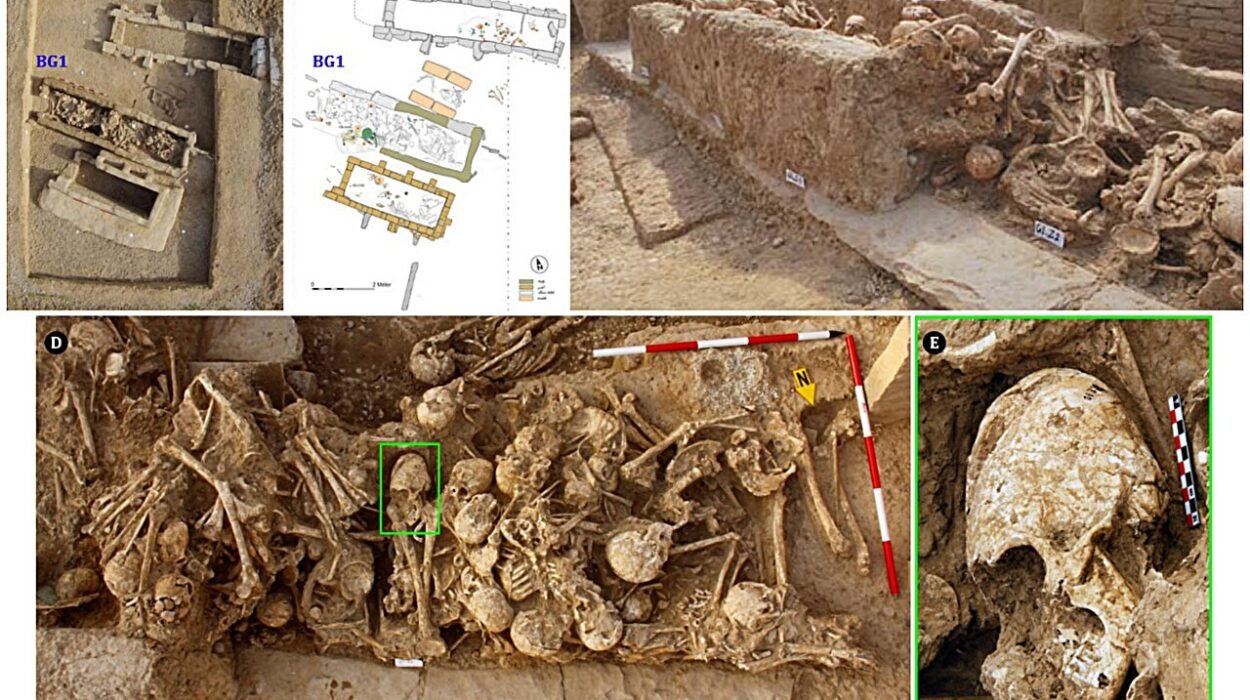

This revelatory study draws upon an interdisciplinary palette of scientific techniques, combining osteological analysis, ethnography, and art history to unearth a story etched into bone. The researchers, led by Jared Carballo and Uroš Matić, examined 30 human skeletons—14 women and 16 men—excavated from the site of Abu Fatima, located near ancient Kerma’s capital. Thanks to meticulous work by the Sudanese-American Mission directed by Sarah A. Schrader and Stuart T. Smith, the skeletons were well-preserved, offering a unique opportunity to compare patterns of physical stress across sexes.

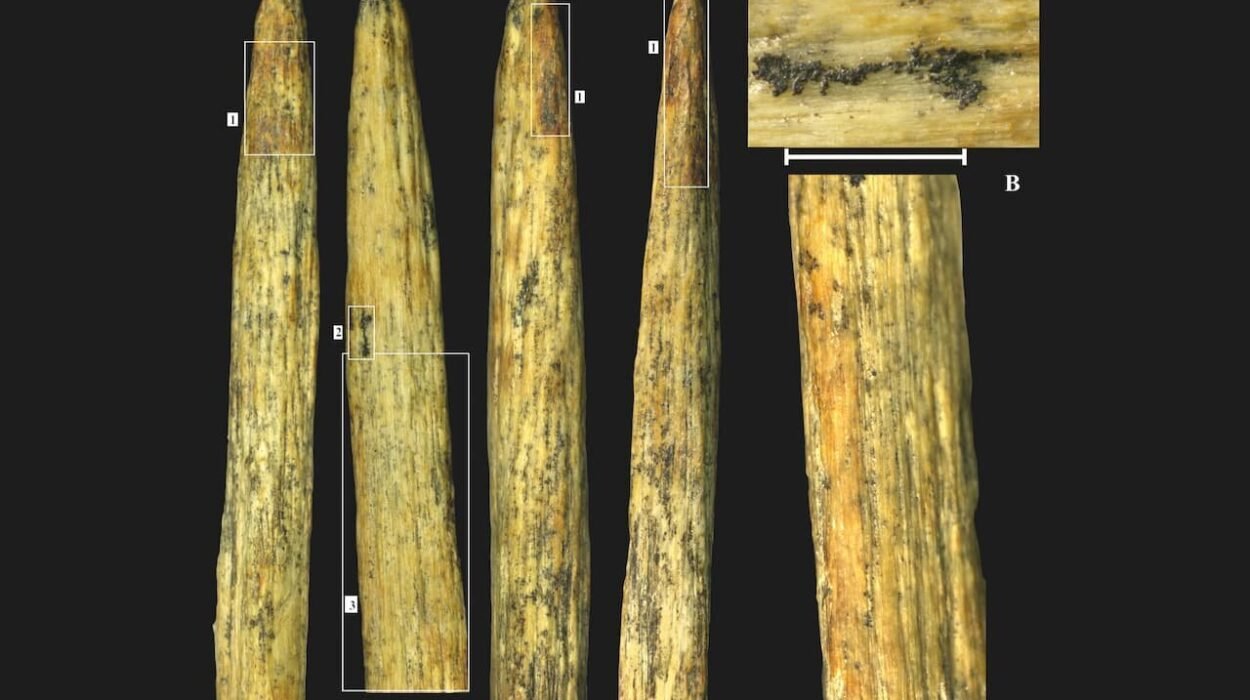

What emerged was a striking divergence in how labor left its mark on the body. Men bore signs of repetitive strain in their shoulders and right arms, indicative of shoulder-loading—perhaps from hauling goods or weapons. But it was the women’s skeletons that told a quieter, more enduring story. Distinctive changes in their cervical vertebrae and skulls—particularly depressions near the coronal suture—suggested the use of tumplines: head straps that transfer weight from the forehead to the back. This technique, still used today in parts of rural Africa, Asia, and Latin America, enables women to carry extraordinary loads with remarkable balance and endurance. It also subtly but persistently reshapes the skeleton.

Among the most compelling individual cases was that of “8A2,” an elderly woman buried with items suggesting both status and migration. An ostrich feather fan and a leather cushion accompanied her in death, signs of comfort and possibly social rank. Yet her body bore the unmistakable imprint of hard labor. Severe osteoarthritis in the neck, combined with wear patterns in her skull, pointed to a life spent bearing weight the way countless women before and after her did—with silent strength and unacknowledged skill. Her dental enamel analysis revealed that she was not native to the region, marking her as a migrant. Here was a woman who, even in advanced age, carried burdens both literal and metaphorical across landscapes and lifetimes.

This single skeleton—at once individual and representative—reveals just how much labor can shape not only societies but the human form itself. It also calls into question centuries of assumptions about who did the heavy lifting in ancient cultures. For generations, prehistory has been painted with broad, masculine strokes: the hunter, the builder, the warrior. But this study makes visible what has long remained hidden—that women, too, were central to survival, infrastructure, and community.

The researchers frame their work through the lens of “body techniques” and “gender performativity”—terms that may sound abstract, but which are deeply human. Every culture trains its members in how to move, work, and carry themselves, often in gendered ways. These repetitive motions leave their trace in the skeleton. Just as a violinist’s shoulder or a blacksmith’s arm betrays a life of skilled labor, so too do the bones of Nubian women reflect the physical knowledge passed down through generations. Carrying a child on the hip, balancing a pot on the head, walking great distances—these are not only cultural practices, they are anatomical ones.

And yet, these embodied histories rarely find their way into textbooks or museums. They are part of what anthropologist Jared Carballo calls “the weight of society” that women have literally carried for millennia. His statement is not a metaphor—it is an anatomical truth. While kings left inscriptions and warriors raised monuments, women like 8A2 sculpted their legacy in the fibers of muscle and the curvature of spine. Their stories were not written in ink but in calcium and collagen.

Importantly, the study does more than recover an overlooked practice; it reframes the very way we understand history. By treating the body as a biological archive—one that records daily routines, social roles, and even inequality—this research bypasses the limitations of written texts and iconography. It shows that even in the absence of documentation, science can reconstruct lives of extraordinary detail. In doing so, it also gives voice to those who were not kings or scribes or generals, but mothers, workers, migrants, and caretakers.

The implications of these findings are profound. They suggest that head-loading, far from being a marginal activity, was central to the economic and social fabric of Nubian society. It enabled women to transport food, water, firewood, and possibly even trade goods across long distances. It played a crucial role in child-rearing and domestic labor. And it did so at a cost—osteoarthritis, spinal stress, and altered cranial morphology. These were not incidental byproducts; they were the price of participation in a physically demanding world.

Moreover, the ethnographic and iconographic parallels explored by the team show that this pattern of head-loading by women is not unique to ancient Nubia. Across time and geography, from ancient Egypt to modern Ethiopia, women have performed similar tasks using similar techniques. Egyptian tomb paintings depict Nubian women bearing offerings and loads on their heads, often in postures that echo the skeletal evidence found at Abu Fatima. These images, once considered decorative or symbolic, now resonate with anthropological insight—they show lived realities captured in pigment and posture.

The study also repositions the Nile Valley in global conversations about gender and labor. Too often, African archaeology has been treated as peripheral or exotic. But in revealing how gendered labor shaped not just economies but anatomies, this research places ancient Nubia at the forefront of cutting-edge science. It also intersects with contemporary questions about the division of labor, bodily autonomy, and the physical toll of caregiving—a reminder that the past is never truly past.

As researchers continue to explore the implications of these findings, new avenues emerge. What were the long-term health outcomes of such labor? Did social status mediate the physical demands placed on women? How did childbirth intersect with skeletal stress from load-carrying? These are questions that bridge anthropology, medicine, and gender studies. They also point to a broader truth: that history is not only what we choose to remember but also what we fail to see.

At the heart of it all lies a powerful irony. The very women whose lives were overlooked by scribes, unmentioned in royal decrees, and minimized in scholarly narratives left behind a record more enduring than papyrus or stone. Their bones tell a story of resilience, routine, and the invisible architecture of society. They reveal a truth so physically grounded it cannot be denied: that civilization has always rested, quite literally, on women’s shoulders.

In a world still reckoning with gender inequality, this study is not just about the past—it is a mirror for the present. It challenges assumptions about strength and visibility, about who gets remembered and why. It urges us to reconsider the architecture of our historical narratives and to ask, with fresh eyes and sharper tools, what stories lie hidden in the structures we inherit. The skeletons of Abu Fatima may have lain silent for 3,500 years, but their voices now ring out with clarity. They remind us that history is not always written by the victors—sometimes, it is written in the vertebrae of the overlooked.

More information: Jared Carballo-Pérez et al, Tumplines, baskets, and heavy burden? Interdisciplinary approach to load carrying in Bronze Age Abu Fatima, Sudan, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jaa.2024.101652