Deep in the shadows of the North Caucasus Mountains, beneath layers of time and sediment, an artifact has emerged that may forever shift how we view our closest ancient relatives. In a cold cave tucked within the rugged Russian terrain, an international team of archaeologists has uncovered a spear tip—modest in length, yet monumental in implication. This is no ordinary fragment of bone. Measuring just 9 centimeters, it bears the fingerprints of ingenuity etched by a species once dismissed as primitive. Through its careful study, we are beginning to hear the whispers of Neanderthals—craftspeople, hunters, and thinkers—across a gulf of 80,000 years.

The discovery was actually made more than two decades ago, in 2003, when a team was excavating a sediment layer within a little-known cave in the North Caucasus. Alongside the remains of long-dead animals—bones from deer, bison, and other prey—archaeologists noted something strange and intriguing: a sharply pointed piece of bone, unlike the others, and clearly shaped by deliberate hands. The layer also held the blackened remnants of an ancient campfire. But it was not until recently, with the benefit of modern imaging and analytical technologies, that the full significance of this bone point came into focus.

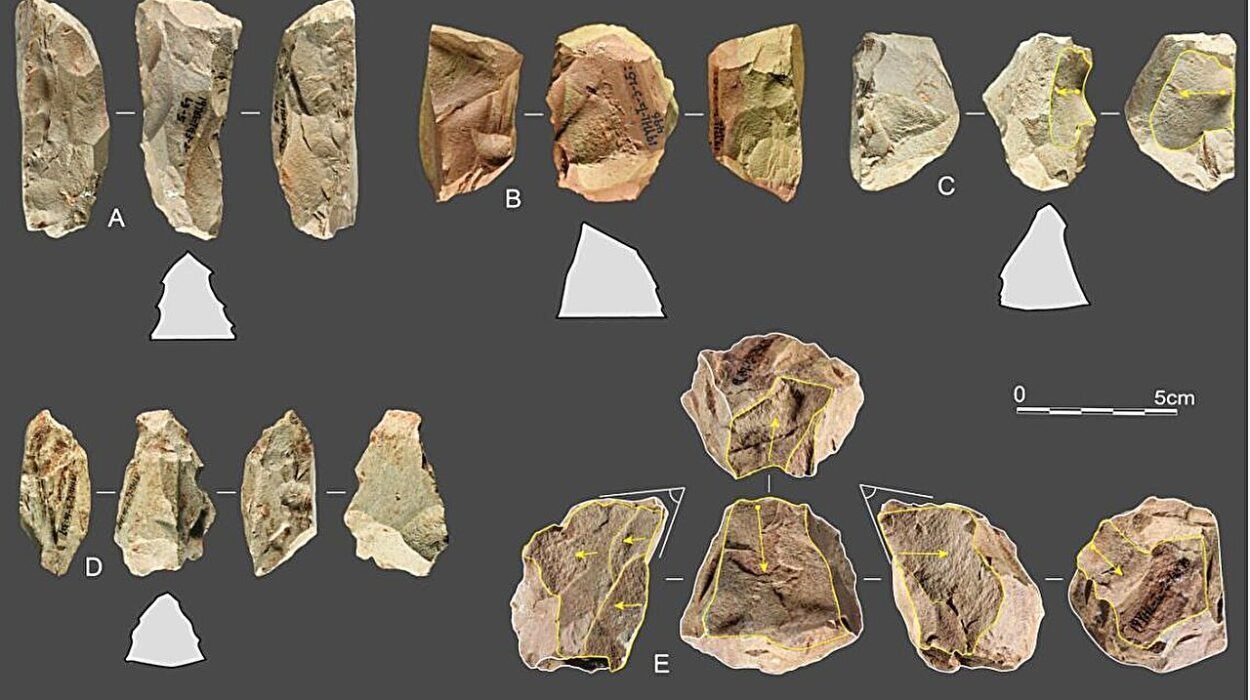

Using a blend of spectroscopy, computed tomography (CT) scans, and microscopic examination, scientists were able to unravel the story written into the very structure of the artifact. The spear tip had been made from the dense leg bone of a large mammal, most likely a bison—an animal that roamed the frigid steppes of prehistoric Eurasia in great herds. Its shape was no accident. Under high magnification, fine striations revealed it had been carved, flaked, and smoothed using sharp stone tools. This was not a broken splinter; it was a carefully fashioned weapon, honed with deliberate technique.

The team’s analysis showed that this tool was not just about form, but function. Along the spear tip’s surface were hairline cracks, tiny but telling, consistent with high-impact collisions. Something hard had met the point with force—perhaps the ribs of an animal, or the body of a rival. This was a weapon that had done its job. What was equally fascinating was what wasn’t there: no signs of prolonged use or wear, no re-sharpening or repair. This tip had been made, used successfully, and then discarded or lost—perhaps in the very act of taking down prey. It was a moment of purpose frozen in time.

Radiocarbon dating and other stratigraphic methods allowed the researchers to pinpoint the spear tip’s age to between 80,000 and 70,000 years ago. This alone is revolutionary. Homo sapiens, our own species, did not arrive in Europe until around 45,000 years ago. The implication is clear and profound: this weapon predates us. It was the work of Neanderthals, a hominin species long believed to be intellectually inferior and technologically stagnant. This one small object, sharp and silent, speaks volumes to the contrary.

For decades, mainstream theories portrayed Neanderthals as static stone-tool users. They were thought to lack the imagination or sophistication required to manipulate materials beyond flint or obsidian. This assumption, like so many others about our extinct cousins, is increasingly being dismantled. Bone tools have been found before, but often in ambiguous contexts or associated with modern humans. This spear tip, securely dated and found in a Neanderthal-occupied context, is the oldest of its kind in Europe. And it changes everything.

What’s particularly astonishing is the technological complexity behind it. To make this weapon, Neanderthals had to select the right type of bone—one that was strong and dense. They had to prepare it using stone implements, which required precise control and knowledge of how bone would respond to pressure and abrasion. Then, they affixed it to a wooden shaft using tar, likely derived from birch bark. Tar production is no simple task. It involves heating organic material in the absence of oxygen, a process that requires not only fire, but foresight and experimentation. In essence, it’s early chemistry.

In this way, the spear tip does more than poke holes in flesh—it punches holes in the narrative of Neanderthal inferiority. It reveals a mind capable of planning, of anticipating needs, of mastering multiple materials and assembling them into a composite tool. The tar binding suggests strategic thinking: how to create a weapon that wouldn’t slip apart in the chaos of a hunt. These hominins weren’t merely reacting to their environment; they were manipulating it, bending nature to serve a purpose.

And yet, as with all remarkable discoveries, this one raises new mysteries. Chief among them: why is this artifact so rare? If Neanderthals were capable of producing such weapons, where are the others? Shouldn’t we have unearthed dozens, if not hundreds, by now?

The research team offers a compelling hypothesis. Bone, unlike stone, is organic and far more prone to decay. Its preservation depends on very specific environmental conditions—dryness, cool temperatures, minimal disturbance. The North Caucasus cave, sealed under layers of sediment, offered just such a haven. Most Neanderthal hunting grounds were not so fortunate. Spears lost on open plains or in forested areas likely decomposed, erased by time. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; rather, it is the echo of impermanence.

This singular spear tip therefore becomes a vital keyhole into a much larger reality. It suggests that Neanderthals may have routinely used bone implements alongside stone ones. Perhaps they had entire toolkits, finely tuned for different tasks—some perishable, some not. What we find in the archaeological record is a biased snapshot, shaped by what happened to survive. For every spear tip we discover, how many others were lost to the soil?

The cultural implications are equally profound. A spear is not just a tool—it’s a symbol. It reflects cooperation, social learning, perhaps even teaching. One individual could not have hunted bison alone; the crafting of such a weapon implies communal knowledge, shared practices, and perhaps even rituals around the hunt. This is not the behavior of a mindless brute. This is the behavior of a society.

Moreover, the spear tip aligns with a growing body of evidence suggesting that Neanderthals were far more complex than we once imagined. They buried their dead. They made pigments and jewelry. They may have had language. They painted on cave walls. Each discovery adds another brushstroke to a portrait that is becoming harder and harder to ignore: Neanderthals were not a failed experiment in evolution. They were an intelligent, adaptive, and creative species with a deep understanding of the world around them.

And then there is the emotional resonance. In the tip of this spear, one can sense the tension of the hunt—the pounding hearts, the whispered strategies, the final charge. One can almost feel the weight of survival resting on the success of this single tool. It connects us to a lineage of risk and innovation, a lineage that is not exclusively ours. It reminds us that the story of intelligence is not written solely by Homo sapiens. It is shared.

The implications for paleoanthropology are thrilling. If one overlooked artifact can reveal so much, what else lies buried? How many assumptions still await to be upended? The field is undergoing a quiet revolution, one bone, one spark of tar, one cave layer at a time.

This spear tip, sharpened so long ago by an ancient hand, cuts through millennia to offer us a gift: a clearer glimpse into the Neanderthal mind. It reveals not just survival, but strategy; not just instinct, but innovation. It is a reminder that the past is not a monologue but a dialogue—between evidence and imagination, between discovery and understanding. And in that dialogue, the Neanderthals are finally beginning to speak.

More information: Liubov V. Golovanova et al, On the Mousterian origin of bone-tipped hunting weapons in Europe: Evidence from Mezmaiskaya Cave, North Caucasus, Journal of Archaeological Science (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106223