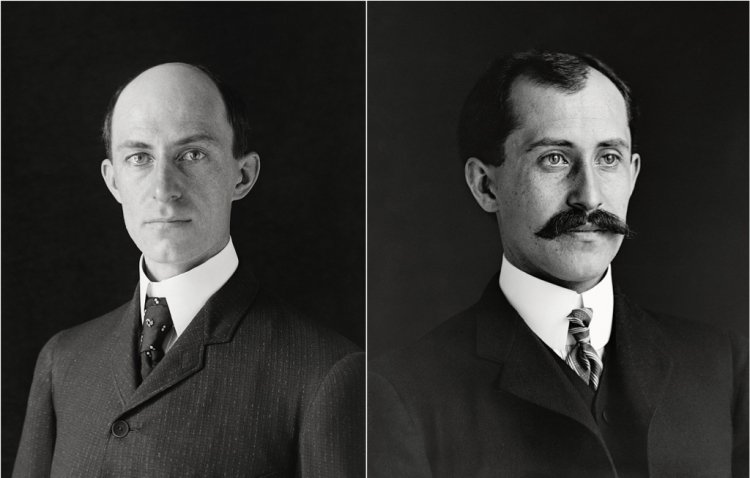

The Wright brothers, Orville (1871–1948) and Wilbur (1867–1912), were pioneering American inventors and aviation pioneers who are credited with inventing, building, and flying the world’s first successful powered airplane. Born in Dayton, Ohio, the brothers developed a strong interest in flight from a young age, influenced by their work in printing and bicycle repair. Their fascination with aerodynamics and mechanical engineering led them to design and build a series of gliders, eventually culminating in the Wright Flyer. On December 17, 1903, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, they made history with the first controlled, sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft. This achievement marked the birth of modern aviation and revolutionized transportation, warfare, and global connectivity. The Wright brothers’ relentless experimentation and innovative spirit laid the foundation for the aerospace industry, making them two of the most influential figures in the history of technology.

** Early Life and Background**

Wilbur Wright was born on April 16, 1867, near Millville, Indiana, while his younger brother Orville Wright was born on August 19, 1871, in Dayton, Ohio. They were two of seven children born to Milton Wright, a bishop in the United Brethren in Christ Church, and Susan Koerner Wright, who had a strong interest in mechanical devices. The family valued education and learning, fostering an environment where curiosity and experimentation were encouraged. Milton Wright’s library, which contained a wide range of books on subjects from science to history, played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual development of Wilbur and Orville.

The Wright brothers’ early fascination with flight can be traced back to a toy helicopter that their father brought home in 1878. The toy was based on an invention by French aeronautical pioneer Alphonse Pénaud and was made of bamboo, cork, and paper, powered by a rubber band. Wilbur and Orville were captivated by the way the toy flew, and they began experimenting with their own versions of it. This early interest in flight never waned and would later form the foundation for their groundbreaking work in aviation.

Wilbur was a bright and ambitious student with plans to attend Yale University after high school. However, his aspirations were derailed when, at the age of 18, he was struck in the face by a hockey stick during a game, leading to severe injuries. The physical and psychological impact of the injury caused Wilbur to withdraw from school and isolate himself for a period. This incident marked a turning point in his life, shifting his focus from formal education to self-directed learning and mechanical experimentation.

Orville, on the other hand, was more of a hands-on learner with a keen interest in printing and mechanical devices. In 1889, at the age of 18, Orville started his own printing business, using a press that he had built with Wilbur’s help. The brothers worked together on the business, which published a variety of materials, including a local newspaper called the “West Side News.” This venture was one of their first successful collaborations and demonstrated their complementary skills—Wilbur’s intellectual curiosity and Orville’s practical ingenuity.

The Wright brothers’ early experiences in printing and their later interest in bicycles provided them with valuable technical skills that would prove essential in their aeronautical experiments. Their work with bicycles, in particular, taught them about balance, control, and the importance of lightweight structures—concepts that would be critical in their development of the first successful powered airplane.

By the mid-1890s, the Wright brothers had shifted their focus from printing to the burgeoning bicycle industry. In 1892, they opened a bicycle sales and repair shop in Dayton, which they later expanded into the Wright Cycle Company. The success of their bicycle business provided them with the financial resources to fund their aviation experiments. More importantly, it gave them a deep understanding of mechanics, material strength, and the principles of balance and control—skills that would be directly applicable to their work in aviation.

The bicycle business also allowed the Wright brothers to pursue their interest in flight more seriously. Inspired by the work of earlier aviation pioneers such as Otto Lilienthal, Samuel Langley, and Octave Chanute, the brothers began studying the principles of aerodynamics and experimenting with gliders. They recognized that controlled flight was the key challenge, and they focused their efforts on understanding how to achieve stability and control in the air.

Wilbur and Orville Wright’s upbringing in a supportive and intellectually stimulating environment, combined with their early exposure to mechanical devices and their experience in the bicycle business, laid the foundation for their groundbreaking work in aviation. Their curiosity, ingenuity, and determination to solve the challenges of flight would eventually lead them to one of the most significant achievements in human history—the invention of the first successful powered airplane.

The Road to Flight: Early Experiments

The Wright brothers’ journey into the world of aviation began in earnest in the late 1890s. Their fascination with flight was rekindled by the death of German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal, who had made significant advancements in glider design and control. Lilienthal’s tragic death in a glider crash in 1896 underscored the dangers of flight but also highlighted the potential for scientific exploration and advancement in the field. Inspired by Lilienthal’s work and determined to build on it, the Wright brothers decided to focus their efforts on understanding the principles of aerodynamics and the mechanics of flight.

The brothers began their research by studying the works of other aviation pioneers and experimenting with different designs. They were particularly interested in the concept of “wing warping,” a method of controlling an aircraft by twisting its wings to change the angle of attack and thus control its direction. This concept, which they initially applied to kites, would later become a crucial component of their aircraft design.

In 1899, the Wright brothers constructed their first experimental kite, a biplane with a wingspan of about five feet. This kite allowed them to test their theories on wing warping and control surfaces. The success of these experiments convinced them that they were on the right track, and they began to focus on building a full-sized glider.

The Wright brothers’ first full-scale glider, constructed in 1900, was tested at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. They chose Kitty Hawk for its consistent winds and soft sand dunes, which provided a safe environment for testing. The 1900 glider had a wingspan of 17 feet and was designed based on the brothers’ calculations of lift and drag. However, the glider did not perform as well as they had hoped. It produced less lift than expected and had stability issues.

Undeterred, the Wright brothers returned to Dayton and began analyzing the data from their tests. They realized that the existing scientific data on lift and drag were incomplete or incorrect. To address this, they built a wind tunnel in their bicycle shop in 1901, where they conducted a series of experiments to better understand the forces at work in flight. This wind tunnel was a crucial innovation that allowed them to test different wing shapes and angles of attack under controlled conditions.

The results of their wind tunnel experiments led the Wright brothers to design their second glider in 1901. This glider had a larger wingspan of 22 feet and featured an improved wing design based on their wind tunnel data. The 1901 glider performed better than the first, but it still had issues with control, particularly in pitch stability.

Frustrated by these setbacks, the Wright brothers sought advice from Octave Chanute, a prominent engineer, and aviation pioneer. Chanute had been following the brothers’ work with interest and provided valuable feedback and encouragement. He also introduced them to the idea of using a movable horizontal stabilizer (elevator) to improve pitch control.

In 1902, the Wright brothers built their third glider, incorporating the movable elevator and further refining their wing design based on their wind tunnel data. This glider, with a wingspan of 32 feet, was a significant improvement over the previous models. During their tests at Kitty Hawk in 1902, the brothers made nearly 1,000 successful glides, demonstrating their ability to control the aircraft in all three axes: pitch, roll, and yaw. This success marked a major breakthrough in their quest for controlled flight.

The 1902 glider also featured a key innovation that would become a hallmark of the Wright brothers’ aircraft designs: a system of interconnected controls that allowed the pilot to simultaneously adjust the elevator and wing warping mechanism. This system gave the pilot precise control over the aircraft’s movements and was a critical factor in the success of their later powered flights.

By the end of 1902, the Wright brothers had solved the fundamental problems of flight: lift, control, and stability. They were now ready to take the next step: building a powered aircraft capable of sustained, controlled flight. The lessons learned from their early experiments, their methodical approach to problem-solving, and their willingness to challenge existing scientific assumptions all contributed to their eventual success as pioneers of aviation.

The First Powered Flight

With the success of their 1902 glider, the Wright brothers were confident that they were ready to tackle the challenge of powered flight. They began work on their first powered aircraft, the Wright Flyer, in the winter of 1902-1903. The Flyer would incorporate all the knowledge they had gained from their glider experiments, along with a new, lightweight engine designed specifically for the aircraft.

One of the biggest challenges the Wright brothers faced was finding a suitable engine for their aircraft. At the time, internal combustion engines were still relatively new, and there were no commercially available engines that were both powerful and lightweight enough for their needs. Undeterred, the Wright brothers decided to design and build their own engine. Working with their mechanic, Charles Taylor, they developed a four-cylinder, water-cooled engine that produced 12 horsepower and weighed just 180 pounds. This engine, combined with a pair of custom-designed propellers, would provide the necessary thrust to propel the Flyer into the air.

The Wright Flyer was a biplane with a wingspan of 40 feet, 4 inches, and a length of 21 feet, 1 inch. It was constructed primarily of spruce wood and covered with muslin fabric. The aircraft featured a forward-mounted elevator for pitch control, a wing-warping mechanism for roll control, and a vertical rudder for yaw control. The pilot lay prone on the lower wing to reduce drag, operating the controls with a series of levers and cables.

By December 1903, the Wright brothers were ready to test their aircraft. They returned to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, where they had conducted their previous glider tests. After several weeks of assembling the Flyer and waiting for the right weather conditions, they finally attempted their first powered flight on December 14, 1903. Wilbur won the coin toss to determine who would pilot the first flight. However, the first attempt did not go as planned. The Flyer stalled during takeoff and crashed after a brief hop, damaging the aircraft. Despite this setback, the Wright brothers were undeterred. They spent the next three days repairing the Flyer and preparing for another attempt.

On December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers made history. With cold, windy conditions providing the necessary lift, they prepared for a series of four flights. This time, it was Orville who took the controls for the first flight. At 10:35 a.m., the Wright Flyer lifted off from a makeshift rail track and flew for 12 seconds, covering a distance of 120 feet. This was the first powered, controlled, and sustained flight of an aircraft, a monumental achievement in the history of aviation.

Over the course of the next few hours, Wilbur and Orville took turns piloting the Flyer, gradually increasing the distance and duration of their flights. On the fourth and final flight of the day, Wilbur managed to stay aloft for 59 seconds, covering a distance of 852 feet. This flight demonstrated that the Flyer was capable of sustained, controlled flight, a feat that had eluded all previous aviation pioneers.

The success of the Wright brothers’ powered flights on December 17, 1903, marked the culmination of years of painstaking research, experimentation, and innovation. Their methodical approach to solving the problems of flight, combined with their mechanical ingenuity and perseverance, had finally paid off. They had achieved what many had thought impossible—the invention of a practical, powered airplane.

The significance of the Wright brothers’ achievement cannot be overstated. They had not only built and flown the first powered airplane, but they had also developed a fundamentally new approach to flight, one that emphasized control and stability. Their use of wing warping, the movable elevator, and the interconnected control system set their aircraft apart from all others and laid the foundation for modern aeronautical engineering.

Despite the success of their flights at Kitty Hawk, the Wright brothers were cautious about publicizing their achievement. They were keenly aware of the competitive nature of the aviation field and wanted to protect their invention through patents before making it widely known. As a result, they kept the details of their flights largely under wraps, sharing the news only with close friends, family, and a few scientific colleagues.

In the months following their historic flights, the Wright brothers continued to refine their aircraft and prepare for the next phase of their work: demonstrating the capabilities of their invention to the world and securing its commercial potential. They returned to Dayton, Ohio, where they focused on perfecting their aircraft’s design and improving its performance.

The Wright brothers’ first powered flight on December 17, 1903, was a turning point in the history of aviation. It was the moment when human flight transitioned from a dream to a reality, and it marked the beginning of a new era in transportation and exploration. The Wright brothers had proven that powered, controlled flight was possible, and their achievement would inspire generations of aviators and engineers to push the boundaries of what was possible in the air.

Developing the Wright Flyer and Public Recognition

After their successful flights at Kitty Hawk in 1903, the Wright brothers returned to Dayton, Ohio, where they continued to work on improving their aircraft. Their primary goal was to build a more reliable and controllable airplane that could fly for longer distances and at higher speeds. This period of development, from 1904 to 1905, would prove to be crucial in solidifying their place as pioneers in aviation.

The Wright brothers began by constructing a new version of their aircraft, known as the Wright Flyer II. This airplane featured several improvements over the original Flyer, including a more powerful engine and a larger wingspan. The Flyer II was first flown in May 1904 at Huffman Prairie, a cow pasture near Dayton that the brothers had chosen as their new testing site. Unlike the isolated dunes of Kitty Hawk, Huffman Prairie allowed them to conduct their experiments closer to home and under more varied weather conditions.

The early flights of the Wright Flyer II were challenging, and the aircraft initially struggled to achieve the same level of performance as the original Flyer. However, the brothers’ persistent efforts to refine their control systems and improve the engine eventually paid off. By the end of 1904, they had made significant progress, achieving longer flights and better control over the aircraft.

One of the key innovations during this period was the development of a catapult launch system, which allowed the Wright brothers to achieve sufficient speed for takeoff without relying on strong winds. This system, which used a weight dropped from a tower to pull the aircraft along a rail track, became an essential part of their flight operations and contributed to the success of their later flights.

In 1905, the Wright brothers introduced their most advanced aircraft yet, the Wright Flyer III. This airplane incorporated all the lessons learned from their previous experiments and featured further refinements in design and control. The Flyer III was more stable, easier to control, and capable of flying for longer distances than its predecessors. On October 5, 1905, Wilbur Wright flew the Flyer III for 24 miles in 39 minutes, circling Huffman Prairie multiple times and demonstrating the aircraft’s ability to sustain flight over a significant distance.

The success of the Wright Flyer III marked a turning point in the brothers’ quest for recognition and commercial success. They had proven that their aircraft was capable of practical flight, and they began seeking opportunities to demonstrate their invention to the world. However, the Wright brothers were also keenly aware of the need to protect their intellectual property. They had filed for a patent for their flying machine in 1903, but the process was slow, and they were reluctant to make public demonstrations until their patent was secured.

As a result, the Wright brothers kept a low profile during this period, avoiding public exhibitions and sharing only limited information about their achievements. This strategy frustrated some members of the scientific community and the press, who were skeptical of the brothers’ claims and eager for proof. Nevertheless, the Wrights remained focused on their goal of securing patents and finding buyers for their aircraft.

In 1906, the Wright brothers were granted a patent for their flying machine, which covered their method of controlling an aircraft through wing warping and other innovations. With this legal protection in place, they began actively seeking commercial opportunities, both in the United States and abroad. They corresponded with potential buyers, including the U.S. government and European military officials, and offered to conduct demonstration flights to prove the capabilities of their aircraft.

The first public demonstrations of the Wright brothers’ aircraft took place in 1908, five years after their initial success at Kitty Hawk. Orville Wright conducted a series of flights at Fort Myer, Virginia, for the U.S. Army, while Wilbur Wright traveled to France to demonstrate their aircraft to European audiences. These demonstrations were a resounding success, earning the Wright brothers widespread acclaim and establishing them as the leading pioneers of aviation.

Wilbur’s flights in France were particularly significant, as they dispelled any lingering doubts about the Wright brothers’ achievements. European aviators and engineers, who had been skeptical of the Wrights’ claims, were astonished by the capabilities of their aircraft. Wilbur’s mastery of flight control and his ability to perform complex maneuvers, such as banking turns and figure-eights, demonstrated that the Wright brothers had not only invented the first powered airplane but had also perfected the art of controlled flight.

The public recognition that followed these demonstrations marked a major turning point in the Wright brothers’ lives. They were hailed as heroes and pioneers, and their success opened the door to lucrative contracts with governments and private companies. The Wright brothers had achieved their goal of proving the viability of powered flight, and they were now poised to capitalize on their invention.

Business Ventures and Legal Battles

With their successful public demonstrations in 1908, the Wright brothers became internationally renowned figures, and their invention was recognized as a major breakthrough in aviation. However, along with fame and recognition came new challenges, including the need to navigate complex business ventures and legal battles to protect their intellectual property and commercial interests.

One of the Wright brothers’ primary goals was to secure contracts for their aircraft, particularly with military organizations. After the successful demonstrations at Fort Myer, Virginia, in 1908, the U.S. Army expressed interest in purchasing a Wright airplane for military use. In February 1909, the Wright brothers signed a contract with the U.S. Army Signal Corps to deliver a military aircraft capable of carrying two people and flying at a speed of at least 40 miles per hour. This contract was a significant achievement for the Wright brothers and marked the first sale of a military aircraft in history.

Around the same time, the Wright brothers were also pursuing commercial opportunities in Europe. Wilbur’s successful demonstrations in France had generated considerable interest from European governments and private investors. In 1909, the Wright brothers formed the Wright Company in the United States and a separate company, the Compagnie Générale de Navigation Aérienne, in France, to manage their business interests and production of aircraft. These companies were responsible for manufacturing and selling Wright airplanes, as well as training pilots to operate them.

Despite their commercial success, the Wright brothers faced significant challenges in protecting their patents and intellectual property. As aviation became increasingly popular, other inventors and companies began developing their own aircraft, some of which incorporated similar control mechanisms to those patented by the Wright brothers. This led to a series of legal battles over patent infringement, as the Wright brothers sought to defend their inventions and prevent others from profiting from their work without proper compensation.

One of the most notable legal battles was with the aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss, who had developed an aircraft with ailerons (movable flaps on the wings) for controlling roll. The Wright brothers argued that Curtiss’s use of ailerons infringed on their patent for wing warping, which was a method of controlling roll by twisting the wings of the aircraft. The legal dispute between the Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss became one of the most famous patent battles in the history of aviation, lasting several years and involving multiple lawsuits.

The Wright brothers’ determination to protect their patents was driven by their belief that they deserved to be compensated for their groundbreaking inventions. However, the legal battles took a toll on their finances, time, and energy. The litigation was expensive and time-consuming, and it also created a great deal of tension within the nascent aviation community. While the Wright brothers won several key rulings in court, the ongoing disputes hindered their ability to focus on further innovations and developments in aviation.

As the legal battles raged on, the Wright brothers continued to pursue their business ventures. They established the Wright Company in 1909, which was responsible for manufacturing and selling their aircraft. The company was initially successful, securing contracts with the U.S. military and various foreign governments. The Wright brothers also began training pilots, both civilian and military, to operate their aircraft, further establishing their dominance in the early aviation industry.

However, managing the Wright Company and overseeing its operations proved to be a challenging task. Neither Wilbur nor Orville had much experience in business management, and they struggled to balance their roles as inventors and entrepreneurs. Wilbur, in particular, took on much of the burden of managing the company’s affairs, traveling extensively to negotiate contracts and oversee production. This left Orville to focus on the technical aspects of aircraft development, though the constant demands of the business often pulled him away from his work as well.

The stress of running the company and the ongoing legal battles began to take a toll on Wilbur’s health. He was frequently exhausted and overworked, and by 1912, his health had deteriorated significantly. Tragically, Wilbur contracted typhoid fever and died on May 30, 1912, at the age of 45. His death was a devastating blow to Orville and the entire Wright family, as well as to the aviation community at large.

Wilbur’s passing marked the end of an era for the Wright brothers. Orville was left to carry on their legacy alone, and he struggled to maintain the momentum that they had built together. The Wright Company continued to operate, but it faced increasing competition from other aviation pioneers, including Glenn Curtiss, who had become a dominant force in the industry. The patent disputes with Curtiss and other competitors continued to drag on, draining the company’s resources and diverting attention from innovation.

In 1915, Orville made the difficult decision to sell the Wright Company. He was disillusioned with the business side of aviation and wanted to return to his roots as an inventor and engineer. The company was sold to a group of investors, and Orville retired from the aviation industry. Although he remained active in various engineering and scientific pursuits, he never returned to the forefront of aviation innovation as he had been during the early years of flight.

Despite the challenges and setbacks they faced, the Wright brothers’ contributions to aviation were undeniable. They had not only invented the first powered airplane but had also established the principles of controlled flight that would guide the development of aviation for decades to come. Their legal battles, while contentious, helped to define the boundaries of intellectual property in the field of aviation and set important precedents for future inventors.

The Wright brothers’ legacy extended beyond their technological achievements. They had shown the world that human flight was possible and had inspired a generation of aviators and engineers to push the boundaries of what was possible in the air. Their relentless pursuit of innovation, their meticulous approach to problem-solving, and their unwavering belief in the potential of flight had transformed the world in ways that few could have imagined.

Legacy and Impact on Aviation

The legacy of the Wright brothers is deeply woven into the fabric of modern aviation and aerospace engineering. Their pioneering work laid the groundwork for the rapid advancement of flight technology in the 20th century and beyond. The principles they established—particularly in the areas of controlled flight, aerodynamics, and aircraft design—continue to influence the field to this day.

One of the most significant aspects of the Wright brothers’ legacy is their emphasis on the importance of control in flight. Prior to their experiments, many aviation pioneers had focused primarily on achieving lift and propulsion, often neglecting the critical issue of stability and control. The Wright brothers, however, recognized that the ability to control an aircraft in three dimensions—pitch, roll, and yaw—was essential for safe and practical flight. Their development of wing warping, the movable rudder, and the elevator to control pitch set the standard for modern aircraft design and established the foundation for all subsequent developments in flight control systems.

The Wright brothers also made significant contributions to the field of aerodynamics. Their use of wind tunnels to test and refine their wing designs was groundbreaking and demonstrated the importance of scientific experimentation in the development of new technologies. The data they collected from their wind tunnel tests allowed them to optimize the shape of their wings and improve the efficiency and performance of their aircraft. This methodical approach to design and testing became a model for future engineers and helped to elevate aeronautics to a true scientific discipline.

In addition to their technical achievements, the Wright brothers’ legacy is also defined by their impact on the commercialization and popularization of aviation. Their successful demonstration flights in Europe and the United States in 1908 and 1909 captured the public’s imagination and sparked a global interest in aviation. Governments, militaries, and private companies began to recognize the potential of powered flight, leading to a surge in investment and research in the field. The Wright brothers’ efforts to protect their patents and establish a commercial market for their aircraft also set important precedents for the business of aviation, helping to shape the industry as it developed.

The Wright brothers’ impact extended far beyond the early years of aviation. Their innovations and the principles they established influenced the design of aircraft throughout the 20th century, from the biplanes of World War I to the jet-powered fighters and bombers of World War II, and even to the spacecraft that would carry humans to the moon. The basic concepts of lift, thrust, drag, and control that the Wright brothers explored remain fundamental to the design and operation of all types of aircraft and spacecraft today.

The Wright brothers’ legacy is also preserved through numerous honors and memorials that recognize their contributions to aviation. The Wright Flyer, the aircraft that made the first powered flight in 1903, is enshrined at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., where it is displayed as one of the most important artifacts in the history of flight. The Wright brothers themselves have been honored with countless awards and accolades, including the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award in the United States.

In addition to these formal recognitions, the Wright brothers’ story has become an enduring symbol of innovation, perseverance, and the human spirit’s quest to overcome the impossible. Their journey from humble beginnings in Dayton, Ohio, to the heights of aviation history serves as an inspiration to generations of engineers, inventors, and dreamers. The lessons they learned and the principles they developed continue to resonate with anyone who seeks to push the boundaries of what is possible.

The Wright brothers’ impact on aviation is perhaps best summed up by the words of Orville Wright himself, who once reflected on the significance of their achievements: “The airplane stays up because it doesn’t have the time to fall.” This simple statement encapsulates the Wright brothers’ understanding of the delicate balance of forces required to achieve flight—a balance that they mastered and that has allowed humanity to soar to new heights ever since.

In the years following the Wright brothers’ pioneering flights, the aviation industry evolved at an astonishing pace. The principles they established were built upon by countless other innovators, leading to the development of more advanced and capable aircraft. The rapid progress of aviation technology transformed transportation, commerce, and warfare, shrinking the world and bringing people and cultures closer together.

The Wright brothers’ contributions to aviation also had a profound impact on global geopolitics. The ability to project air power became a crucial factor in military strategy, and the development of aircraft for reconnaissance, bombing, and air superiority played a decisive role in the outcome of both World Wars. The Wright brothers’ invention of the airplane not only changed the way wars were fought but also reshaped the balance of power among nations, with those possessing advanced aviation capabilities gaining a significant strategic advantage.

In the realm of commercial aviation, the Wright brothers’ legacy is equally significant. The principles of controlled flight that they established enabled the development of safe and reliable passenger aircraft, leading to the rise of the global airline industry. Today, millions of people around the world rely on air travel for business, leisure, and connection with loved ones, all made possible by the pioneering work of the Wright brothers.

The Wright brothers’ influence can also be seen in the space age. The same principles of aerodynamics and control that they developed for flight within Earth’s atmosphere were adapted for the design of spacecraft capable of navigating the vacuum of space. The Wright brothers’ vision of flight was not limited to the skies of Earth but extended to the exploration of the cosmos, inspiring future generations of engineers and astronauts to push the boundaries of human exploration.

The story of the Wright brothers is a testament to the power of innovation, determination, and the pursuit of knowledge. Their journey from bicycle mechanics to aviation pioneers is a reminder that great achievements often come from humble beginnings and that the drive to solve complex problems can lead to breakthroughs that change the world. The Wright brothers’ legacy continues to inspire and challenge us to reach for new heights, both in aviation and in all areas of human endeavor.

As we look to the future of aviation and aerospace, the Wright brothers’ pioneering spirit remains a guiding light. The challenges of their time—mastering the principles of flight, designing a controllable aircraft, and navigating the complexities of intellectual property—are mirrored in the challenges we face today as we explore new frontiers in aviation and space exploration. Just as the Wright brothers pushed the boundaries of what was possible in their era, modern innovators and engineers are tasked with overcoming new obstacles and advancing the field in ways that were unimaginable just a few decades ago.

One of the areas where the Wright brothers’ legacy continues to resonate is in the development of sustainable aviation. As the world faces the growing challenge of climate change, the aviation industry is under increasing pressure to reduce its carbon footprint and develop cleaner, more efficient technologies. The Wright brothers’ emphasis on scientific experimentation and iterative design serves as a model for today’s engineers, who are working to create electric and hybrid aircraft, develop more efficient propulsion systems, and explore alternative fuels. The pioneering spirit of the Wright brothers lives on in these efforts, as researchers and companies strive to make aviation more sustainable for future generations.

Another frontier where the Wright brothers’ influence is felt is in the field of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drones. The principles of controlled flight that the Wright brothers established are fundamental to the operation of drones, which have become an increasingly important tool in a wide range of industries, from agriculture and logistics to surveillance and environmental monitoring. The Wright brothers’ legacy is also evident in the burgeoning field of urban air mobility, where companies are developing electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft to revolutionize urban transportation and reduce congestion in cities.

Perhaps the most exciting and ambitious extension of the Wright brothers’ legacy is the exploration of space. Just as the Wright brothers’ Flyer was the first aircraft to achieve powered flight, modern space exploration efforts are focused on developing the technologies and capabilities needed to achieve sustained human presence beyond Earth. The Wright brothers’ approach to innovation—combining careful experimentation with a willingness to take risks—remains relevant as engineers and scientists work to develop spacecraft, habitats, and life support systems for missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

The spirit of the Wright brothers is also reflected in the growing interest in supersonic and hypersonic flight. While the Wright brothers’ flights were modest in speed and altitude, their pioneering work laid the foundation for the development of aircraft capable of traveling faster than the speed of sound. Today, companies and researchers are working to develop the next generation of high-speed aircraft, which could dramatically reduce travel times and open up new possibilities for global transportation. The challenges faced by these modern pioneers—such as minimizing sonic booms and ensuring passenger safety—echo the challenges that the Wright brothers confronted in their quest to achieve controlled flight.

As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in aviation and aerospace, the Wright brothers’ legacy serves as a reminder of the power of human ingenuity and the importance of perseverance in the face of challenges. Their story is a testament to the idea that with the right combination of vision, determination, and hard work, even the most audacious goals can be achieved. The Wright brothers’ achievements not only transformed the world during their lifetimes but also set the stage for the remarkable advances that have taken place in the century since their first flight.

In the years since the Wright brothers made history at Kitty Hawk, the world has witnessed a revolution in aviation and space exploration that would have been unimaginable to Orville and Wilbur Wright. The skies that they once pioneered are now filled with thousands of aircraft crisscrossing the globe, and humanity has taken its first steps into the cosmos, exploring the far reaches of our solar system and beyond. Yet, despite all the progress that has been made, the principles that the Wright brothers established remain as relevant today as they were more than a century ago.

The Wright brothers’ story continues to inspire not only those who work in aviation and aerospace but also anyone who seeks to push the boundaries of human knowledge and achievement. Their journey from a small bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, to the forefront of aviation history is a powerful reminder that great things can be accomplished when we dare to dream, question the status quo, and persist in the face of adversity.

As we look to the future, the Wright brothers’ legacy will undoubtedly continue to shape the course of aviation and space exploration. The challenges that lie ahead—whether it is achieving sustainable flight, developing new modes of transportation, or exploring distant worlds—will require the same combination of creativity, innovation, and perseverance that defined the Wright brothers’ approach to flight. In this way, the spirit of Orville and Wilbur Wright will continue to soar, guiding us as we navigate the skies and reach for the stars.

In the end, the Wright brothers’ greatest legacy may not be the aircraft they built or the flights they made but the example they set for future generations. They demonstrated that with vision, hard work, and a relentless pursuit of excellence, even the most impossible dreams can become a reality. Their story is a testament to the power of human ingenuity and the enduring impact that two determined individuals can have on the course of history.