Before the Olympians ruled with thunder and wisdom, before the Titans carved their place in legend, there was a world of raw beginnings—chaotic, untamed, and drenched in mystery. Out of this chaos, the ancient Greeks imagined forces so immense, so elemental, that they were less like personalities and more like the very bones of the universe. Among these primal beings stood Uranus, the vast and infinite sky, whose name still echoes in the stars.

In mythology, Uranus was not just a god—he was the embodiment of the heavens themselves, the dome that arched over the newborn Earth. His union with Gaia, the Earth, gave rise to the first generation of mighty beings who would shape the fate of gods and mortals alike. Yet, his reign was neither peaceful nor eternal. The story of Uranus is one of power, fear, betrayal, and downfall—a cosmic drama that set the stage for the rise of the Titans and, eventually, the Olympians.

Uranus in the Greek Imagination

To the Greeks, the sky was not an empty void. It was a living force, filled with stars, storms, and light. Uranus personified this celestial expanse, a god as infinite as the horizon. Unlike later gods who were imagined in humanlike forms, Uranus retained a more abstract, elemental quality. He was the sky itself, stretching endlessly above Gaia, the Earth, and enclosing her in his embrace.

Together, Uranus and Gaia formed the primal cosmic couple. They were not born of parents but were among the very first beings to emerge after Chaos. In their union, they produced powerful offspring: the Titans, who would later rise to prominence; the Cyclopes, one-eyed giants with unparalleled craftsmanship; and the Hecatoncheires, monstrous beings with a hundred hands and fifty heads, embodiments of raw, untamable force.

Yet, Uranus was not a nurturing father. Instead, he came to fear the very children he had begotten, for their immense power threatened his dominion. This fear set into motion a cycle of cruelty and rebellion that would define his fate.

The Tyranny of the Sky

In Hesiod’s Theogony, one of the earliest and most influential sources of Greek cosmogony, Uranus is portrayed as a harsh and oppressive ruler. His fear of his children drove him to a terrible act: he forced them back into Gaia’s womb, burying them within the depths of the Earth.

Imagine Gaia, the nurturing mother, straining under the unbearable weight of her own imprisoned offspring. The Earth groaned, suffocated by the sky’s relentless pressure. Her children—immortal, powerful, yet trapped—burned with rage and despair. It was a tyranny of cosmic proportions, and Uranus seemed invincible.

But Gaia, though burdened, was not powerless. The Earth herself began to plot. From her fertile body, she shaped a weapon—a sickle of unbreakable adamant, sharp enough to cut through the very flesh of a god. With this blade, she would turn her son against her husband, unleashing the first act of divine rebellion.

Cronus, the Instrument of Rebellion

Of all Uranus’s children, it was Cronus, the youngest of the Titans, who had the courage—or perhaps the ruthlessness—to carry out his mother’s plan. Gaia spoke to her children, urging them to rise against their father’s cruelty. One by one, they trembled and shrank back, unwilling to defy the Sky God. Only Cronus stepped forward, his heart hard with resentment, his ambition fueled by the promise of power.

When Uranus descended once more to lie upon Gaia, the ambush was sprung. From his hiding place, Cronus leapt forward, brandishing the adamant sickle. With a single, brutal stroke, he castrated Uranus, severing his generative power and ending his dominion over the world.

The act was both grotesque and transformative. The severed genitals fell into the sea, and from the foam that rose around them, a new deity was born—Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty, a symbol of life’s power to emerge even from violence. Drops of Uranus’s blood also spilled upon the Earth, and from them sprang the Erinyes (the Furies, avengers of blood), the Giants, and the Meliae (nymphs of the ash tree). Thus, Uranus’s downfall did not merely end his reign; it seeded new powers that would shape the world to come.

The Fall of Uranus and the Rise of Cronus

With Uranus overthrown, Cronus and his fellow Titans were freed from their father’s oppression. They rose to power, establishing the Golden Age, a mythic era of abundance and peace under Titan rule. Uranus, once supreme, receded into the background, his presence lingering only as the starry sky above.

Yet, Uranus’s legacy was not erased. His curse upon Cronus would echo across generations. As he fell, Uranus prophesied that Cronus, too, would be overthrown by his own children, just as he had betrayed his father. This prophecy planted the seed of paranoia in Cronus’s heart, leading him to swallow his children one by one—a cycle of fear and violence that would only end with the rise of Zeus and the Olympians.

Thus, the myth of Uranus became the opening act of a larger cosmic drama: the endless struggle between generations of gods, each overthrowing the last, each haunted by the shadow of betrayal.

Uranus in Hesiod’s Theogony

Our primary source for the myth of Uranus comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, a poem written around the 8th century BCE. In it, Hesiod paints a vivid picture of the origins of the cosmos and the genealogy of the gods. Uranus is introduced as one of the first beings, brought forth by Gaia to be her equal and partner.

The tale of Uranus’s cruelty, Cronus’s rebellion, and the birth of new deities from his downfall is told with stark and brutal imagery. It reflects the Greek view of the cosmos as a place of struggle and succession, where even gods are not free from conflict and fate. The Theogony positions Uranus as a necessary, though flawed, figure—a cosmic father whose overthrow makes way for the order that follows.

Symbolism of the Sky God

The story of Uranus is more than just a myth; it is a symbolic exploration of the relationship between heaven and earth, authority and rebellion, creation and destruction.

Uranus represents the unyielding sky, eternal yet oppressive, pressing down upon the fertile Earth. His act of imprisoning his children in Gaia’s depths reflects the fear of change, the refusal to allow new life and power to emerge. He is the embodiment of stagnation, a cosmic tyrant who clings to control.

Cronus’s act of castration, violent as it is, symbolizes the breaking of old orders to make way for the new. It is an allegory of generational conflict, the inevitable tension between fathers and sons, rulers and successors. In this sense, Uranus’s fall is not just a story of personal betrayal but a mythic truth about the cycles of power and renewal in nature and society.

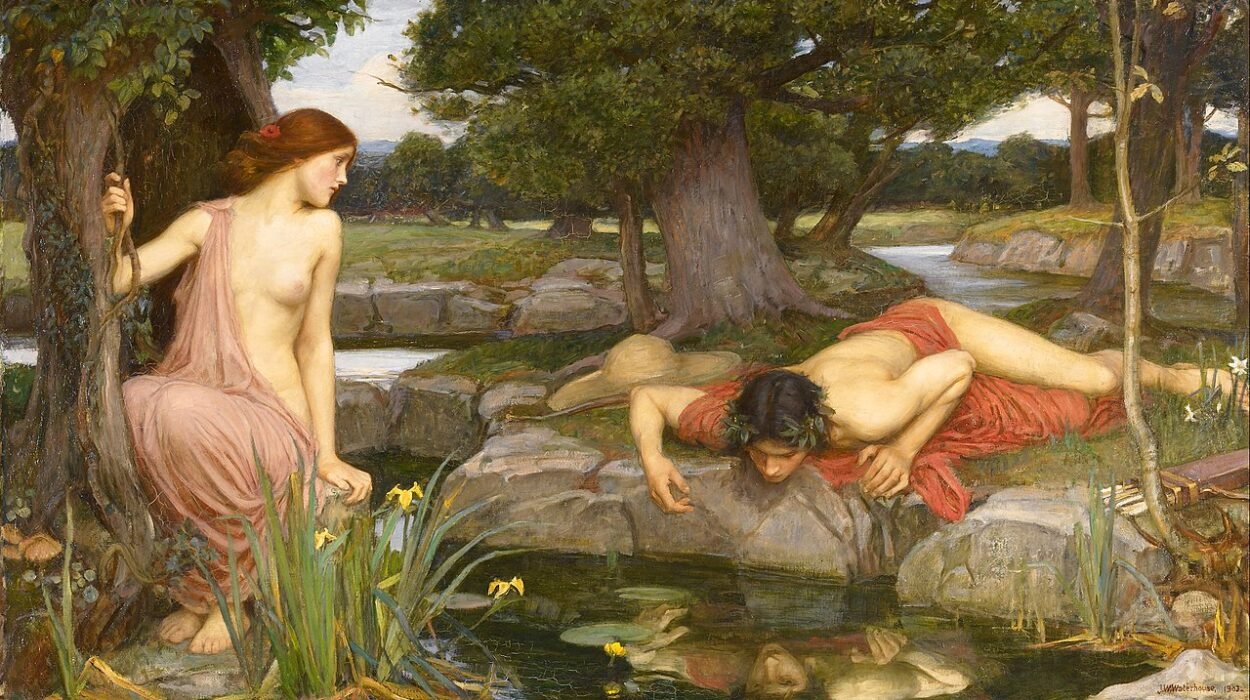

The birth of Aphrodite from Uranus’s severed flesh also underscores the paradox of creation through destruction. From violence comes beauty, from loss comes love. In this way, Uranus’s downfall is both an end and a beginning.

Uranus in Later Thought

Unlike Zeus, Athena, or Apollo, Uranus did not remain a central figure in Greek worship or mythology. After his overthrow, he largely faded into the background, serving more as a primordial ancestor than an active deity. Few temples or cults were dedicated to him, for his role was cosmic rather than personal.

However, his legacy endured in symbolic and philosophical ways. Philosophers and poets often invoked Uranus as the personification of the heavens, the eternal backdrop against which the drama of gods and mortals unfolded. In astrology, Uranus (a name later given to the planet discovered in the 18th century) came to represent sudden change, rebellion, and innovation—fitting echoes of the mythic god’s legacy of upheaval.

The Planet Uranus: Science Meets Myth

In 1781, astronomer William Herschel discovered a new planet in the solar system, the first ever found with a telescope. It was eventually named Uranus, linking modern science back to ancient myth. The choice was fitting: just as the sky god represented the vast dome of the heavens, the planet Uranus marked the expansion of humanity’s cosmic horizon.

Astronomically, Uranus is unique. It rotates on its side, its axis tilted dramatically, as though it had been struck by some cataclysmic event—a celestial echo, perhaps, of the god’s violent fall. The planet’s pale blue hue, its faint rings, and its icy composition make it one of the most enigmatic worlds in our solar system.

Thus, in both myth and science, Uranus is a figure of strangeness and wonder, a symbol of vastness, rebellion, and the unexpected.

The Eternal Legacy of Uranus

Though he may not command temples or prayers, Uranus remains etched into the imagination of humanity. His story is the story of beginnings—the first cosmic struggle, the first overthrow, the first taste of the cycle that would repeat through Titans and Olympians alike.

He is the symbol of a sky that both shelters and oppresses, of a father who fears his children, of a world that must break itself to grow. His downfall gave rise to love, fury, and prophecy, shaping the destinies of gods and men.

And as we look to the heavens, to the stars and the planets, Uranus still gazes back. His name lingers in astronomy, his myth in poetry, his symbolism in philosophy. He is the sky itself—vast, unyielding, and eternal—even in defeat.

The tale of Uranus reminds us that every beginning carries within it the seeds of its own end, and that from endings, new beginnings always rise.