When we look up at the night sky, we are not seeing the present—we are gazing into the deep past. Every star that twinkles in the vast dark sea is a messenger from another time, its light crossing immense distances to whisper stories of creation. Among these celestial storytellers are the oldest stars in the universe—ancient suns born near the dawn of time itself. Their faint glow carries within it the memory of the universe’s earliest moments, long before our Sun, our planet, or even the Milky Way as we know it existed.

The oldest stars are the universe’s living fossils. They are cosmic relics from an era when hydrogen and helium were almost the only elements in existence, when galaxies were just beginning to take shape, and when darkness still clung to the edges of creation. To find them, to study them, is to peer through the veil of time and glimpse the origins of everything we know.

But these stars are more than scientific curiosities. They are poetic symbols of endurance and cosmic history. Each one burns quietly, holding in its heart the chemistry of the first atoms and the secrets of how the universe evolved from chaos into structure, from formless gas into galaxies—and ultimately into us.

The Dawn After the Darkness

To understand the oldest stars, we must return to a time before stars even existed—the epoch known as the “cosmic dark ages.” After the Big Bang, about 13.8 billion years ago, the universe was hot, dense, and filled with a brilliant plasma of light and matter. But as it expanded, that light dimmed and the cosmos cooled. Protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen, and for hundreds of millions of years, space lay shrouded in darkness.

Then, gravity began its quiet work. Tiny fluctuations in the density of matter—left over from the Big Bang—caused hydrogen clouds to collapse. In their dense hearts, pressure and temperature rose until, finally, nuclear fusion ignited. The first stars were born.

These first-generation stars, known as Population III stars, were unlike anything in the modern universe. Composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, they lacked the heavier elements—carbon, oxygen, iron—that later stars contain. They burned ferociously bright and lived short, violent lives, often ending as massive supernovae that scattered the first heavy elements into space.

Though none of these primordial stars are known to survive today, their fingerprints remain in the chemistry of the stars that followed. The oldest stars we can see—ancient survivors from the second or third generation—carry in their atmospheres the faint signatures of those first cosmic explosions. By studying them, astronomers can reconstruct what the universe looked like when it was young.

Population II Stars: The Children of the First Light

After the first stars lived and died, they enriched their surroundings with elements forged in their fiery cores. The next generation of stars—called Population II—formed from this slightly enriched material. These stars, while still incredibly old, contain trace amounts of metals (in astronomy, “metals” means any element heavier than helium).

Population II stars are the oldest still shining today. They formed more than 12 to 13 billion years ago, often in the earliest galaxies or globular clusters—dense, spherical swarms of ancient stars that orbit larger galaxies like the Milky Way.

These stars are time capsules, preserving the chemical fingerprints of the early universe. By measuring the ratios of elements such as carbon, oxygen, and iron in their light spectra, astronomers can deduce how many generations of stars preceded them—and, astonishingly, how quickly the universe went from primordial gas to complex chemistry.

One of the most remarkable findings from studying these stars is that even within the first few hundred million years, the cosmos had already begun to create the ingredients of life. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—essential to biology—were being synthesized and scattered into space by early supernovae. The universe wasted no time in setting the stage for creation.

The Search for the Cosmic Elders

Finding the oldest stars is no simple task. They are rare, faint, and often hidden among younger, more brilliant companions. Astronomers must use both patience and precision, scanning the skies for the telltale signs of ancient origin: low metallicity and unique chemical ratios.

Metallicity is a star’s cosmic birth certificate. Younger stars, like our Sun, contain higher amounts of metals because they were born from gas enriched by countless generations of stellar deaths. Ancient stars, in contrast, are metal-poor—they formed before many heavy elements existed.

The search for metal-poor stars has taken astronomers to the fringes of the Milky Way, where old stars tend to drift in the galactic halo, far from the bustling disk where new stars form. Using high-resolution spectrographs, scientists examine their light in exquisite detail, teasing out the faint fingerprints of elements within.

Among the most ancient known is SMSS J031300.36−670839.3, a star discovered in 2014 in the halo of our galaxy. Its iron content is less than one ten-millionth that of the Sun—essentially pristine material from the early universe. This star likely formed just after the first generation of stars exploded, making it a direct descendant of the universe’s first light.

Another cosmic elder, HE 1523–0901, discovered in 2007, is estimated to be around 13.2 billion years old—almost as old as the universe itself. Its age was measured using radioactive decay, a kind of stellar carbon dating, revealing it was born when the cosmos was less than a billion years old.

Each discovery like this is a triumph—a glimpse of the dawn through the fog of time.

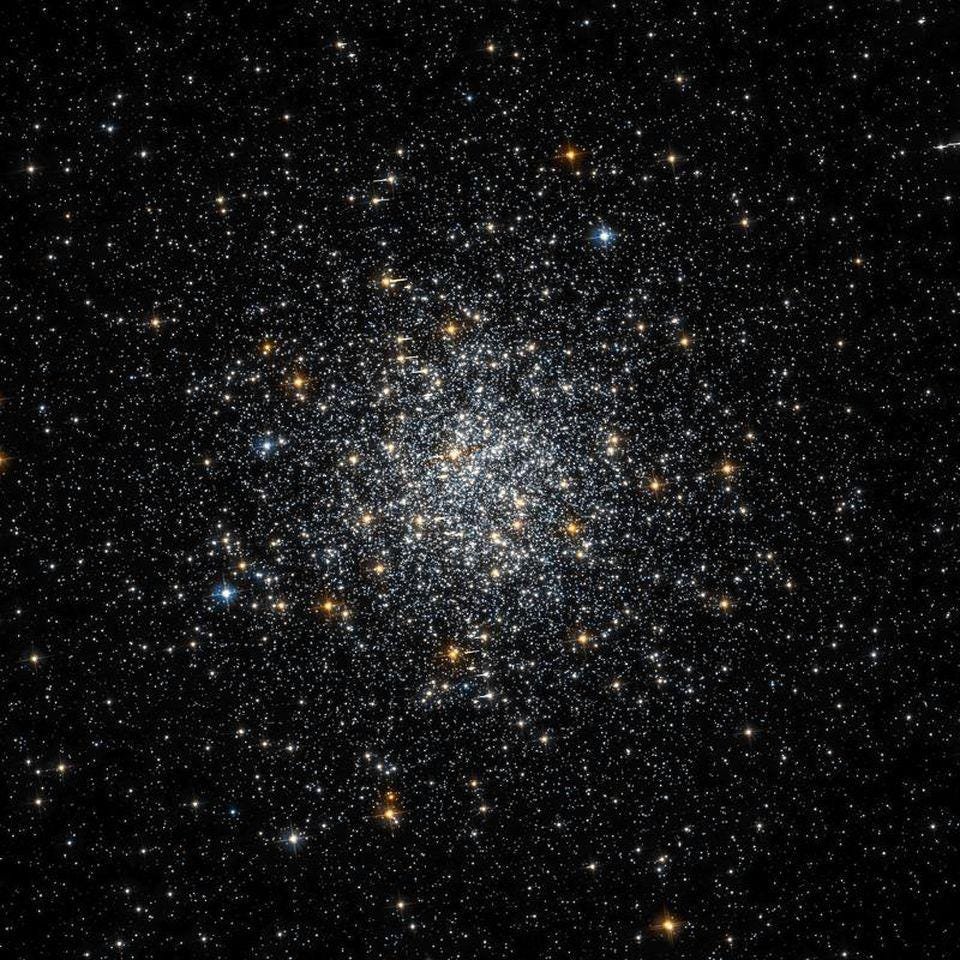

Globular Clusters: The Ancient Cities of Stars

If the galaxy were a city, globular clusters would be its ancient neighborhoods—densely packed, unchanging, and filled with elders. These massive spheres of hundreds of thousands of stars orbit the Milky Way’s outskirts like glittering relics of a forgotten age.

Globular clusters such as M92, Omega Centauri, and 47 Tucanae contain some of the oldest stars known. Their uniform age and chemical composition suggest they formed during the earliest stages of galaxy formation, perhaps even before the Milky Way fully assembled.

Studying globular clusters allows astronomers to test theories of cosmic evolution. For instance, by measuring the color and brightness of stars in these clusters, scientists can estimate their ages with remarkable accuracy. Many clusters are found to be around 12 to 13 billion years old—meaning they began forming when the universe was still glowing with the afterlight of the Big Bang.

But globular clusters are not just ancient—they are resilient. Despite billions of years of gravitational tides, cosmic collisions, and galactic mergers, they have endured. Their survival tells us that the early universe, though chaotic, also possessed regions of remarkable stability where stars could form and remain bound together for eons.

The Chemistry of Creation

Every element in your body was forged in a star. Hydrogen, the most abundant element, was born in the Big Bang. But everything else—carbon in your cells, calcium in your bones, iron in your blood—came from stars that lived and died long before the Sun existed.

The oldest stars teach us how this cosmic alchemy began. When astronomers analyze their light, they can determine the abundance of elements like lithium, carbon, magnesium, and iron. These ratios reveal the nuclear processes of early supernovae—the first furnaces that seeded the cosmos with complexity.

For example, some of the oldest stars are rich in carbon but poor in iron, suggesting they were enriched by massive first-generation stars that exploded in an unusual way, ejecting lighter elements while trapping heavy ones in their remnants. Others show peculiar excesses of certain rare elements, indicating that neutron-capture processes—the same that create gold and uranium—were already operating shortly after the universe’s birth.

Each of these discoveries refines our understanding of how the periodic table came to be written across the cosmos. In a sense, the oldest stars are like cosmic genealogists, tracing the lineage of atoms from the dawn of time to the chemistry of life.

The Galactic Halo: A Graveyard and a Museum

The Milky Way’s halo is a vast, dim sphere surrounding the galaxy’s bright spiral disk. It is sparsely populated, home mostly to ancient stars and clusters that formed long before the galaxy itself took its present shape.

When we look at these halo stars, we’re not just observing survivors—we’re seeing the remnants of galaxies long gone. Many of these stars once belonged to smaller galaxies that merged with the Milky Way billions of years ago. Their distinct chemical signatures act like fossils, allowing astronomers to piece together the Milky Way’s assembly history.

In this way, the halo is both a graveyard and a museum—a place where the ghosts of ancient galaxies still drift, carrying their stories in their light.

Recent surveys using instruments like the Gaia spacecraft have mapped the motion of millions of stars, revealing streams and clumps—cosmic debris from long-vanished galaxies. Among these streams are some of the oldest known stars, their paths tracing the gravitational ballet that built our galaxy.

The Milky Way, it turns out, is a cosmic mosaic—a collection of stellar populations born in different places and times, now woven together through gravity.

What the Oldest Stars Reveal About the Universe

Studying ancient stars is like reading the universe’s autobiography. Each star is a chapter, and together they tell a story of transformation—from simplicity to complexity, from darkness to light.

The oldest stars reveal that the universe began forming structures almost immediately after the Big Bang. Within a few hundred million years, galaxies, clusters, and heavy elements were already taking shape. This rapid evolution challenges earlier assumptions that star formation was a slow, gradual process.

They also show us that the cosmic chemical factory started running early. Even in the universe’s infancy, supernovae were producing carbon, oxygen, and iron—the raw materials for planets and life.

Furthermore, ancient stars help refine our models of cosmology. By comparing their ages to the expansion rate of the universe, scientists can independently verify the age of the cosmos derived from the cosmic microwave background. The fact that the oldest stars are nearly as old as the universe itself provides a stunning confirmation that our cosmological timeline is accurate.

In their light, we also see evidence for the mysterious processes that shaped the first galaxies—how small clumps of matter merged, how star formation began, and how feedback from the first supernovae influenced everything that followed.

When the First Stars Died

The first stars—those massive Population III titans—lived fast and died young. Many exploded as hypernovae, releasing unimaginable energy and scattering newly forged elements across the cosmos. Some collapsed directly into black holes, perhaps seeding the formation of the supermassive black holes that now sit at the centers of galaxies.

The remnants of those long-dead stars echo through time. When we detect the faint traces of certain elements—like barium, europium, or strontium—in the oldest surviving stars, we are seeing the fingerprints of those first deaths imprinted on later generations.

The universe, in its infancy, was a place of creation through destruction. The death of the first stars gave birth to the diversity of elements that made new stars, planets, and eventually life possible.

It is a profound paradox—the first stars had to die so that we could exist.

Cosmic Archaeology: Tools of the Modern Explorer

Modern astronomy is, in many ways, a form of cosmic archaeology. Instead of digging through layers of earth, scientists sift through layers of time and light. They use telescopes as time machines, peering billions of years into the past.

Ground-based observatories like the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope and space-based instruments like the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes allow us to detect faint, distant stars and galaxies that existed when the universe was young.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), in particular, has revolutionized this search. Its infrared vision can pierce the veil of cosmic dust and reveal galaxies that formed less than 400 million years after the Big Bang. Within these early galaxies may lie the ancient stars that illuminate the path from darkness to light.

Meanwhile, detailed spectroscopic surveys—such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and the Gaia mission—map the motion and chemistry of millions of stars, allowing astronomers to identify those with the lowest metallicities and trace the Milky Way’s ancient past.

These technologies combine to form a grand, intergenerational project: humanity’s effort to understand its cosmic ancestry.

The First Galaxies and Their Ancient Stars

The oldest stars do not exist in isolation. They were born in the first galaxies—small, irregular structures that grew from primordial gas. These galaxies merged and evolved, eventually forming the grand spirals and ellipticals we see today.

Observations of these early galaxies show that they were surprisingly efficient at forming stars. Even in an environment nearly devoid of heavy elements, the laws of physics conspired to create light.

By studying the light from distant galaxies, astronomers can estimate their stellar populations and compare them with the metal-poor stars we find locally. The consistency between these two lines of evidence tells us that the oldest stars we see in the Milky Way today are indeed direct descendants of the first galaxies that ever existed.

In a sense, when we study an ancient star in our own galaxy, we are studying the echoes of galaxies that vanished billions of years ago.

The Legacy of the Ancient Light

Every photon from an ancient star is a message across time. It tells us that the universe remembers, that nothing truly disappears without leaving a trace. The light that left a star 13 billion years ago may reach a telescope tonight, carrying with it the memory of a cosmos still in its infancy.

The oldest stars remind us of continuity—the unbroken chain between creation and consciousness. From the nuclear furnaces of the first stars came the elements that would one day form planets, oceans, and life. From the ashes of the early universe came beings capable of looking back and asking, “Where did we come from?”

Physics tells us that energy cannot be destroyed—it only transforms. In that sense, the light of those ancient stars still lives in us. The carbon in our bodies, the oxygen we breathe, and the iron in our blood were once starlight too. We are made of the universe’s memory, shaped by the deaths and rebirths of suns long gone.

The Mystery Still Unfolding

Despite decades of discovery, many mysteries remain. Have we truly found the oldest possible stars? Could some ancient Population III stars still exist, faint and hidden in the outer reaches of galaxies or drifting through intergalactic space?

Astronomers continue to search for these elusive first-generation stars. If one were found, it would be like discovering a living fossil—a direct witness to the universe’s first moments of creation.

Even now, new data from the JWST suggests that galaxies formed earlier and faster than once believed, raising profound questions about how quickly the first stars emerged after the Big Bang. Our understanding of cosmic history is being rewritten, and the oldest stars remain the key to the mystery.

As we push further into the cosmic dawn, each new discovery brings us closer to answering humanity’s oldest question: how did it all begin?

The Universe Remembered in Starlight

The story of the oldest stars is not just a scientific pursuit—it is a human story. It speaks to our desire to remember, to trace our origins, to find meaning in the vastness.

Every ancient star we find is a mirror held up to the beginning of time. Their faint, patient light reveals not only the evolution of galaxies and elements but also the enduring nature of curiosity itself.

From the first spark of nuclear fusion to the complex web of life that now ponders the stars, there is an unbroken thread—a narrative of transformation written in light.

The universe began in darkness. Then came the stars, scattering brilliance across the void. Billions of years later, one small planet around an average star gave rise to creatures who looked up and saw that light, and realized it was home.

The oldest stars remind us that we are part of a story far greater than ourselves—a story that began long before us and will continue long after.

Their glow is not just a window into the past—it is a promise. A promise that the light of creation, however distant, will always find a way to reach the eyes that seek it.

And in that eternal reaching—in that longing to understand—the universe comes to know itself once more.