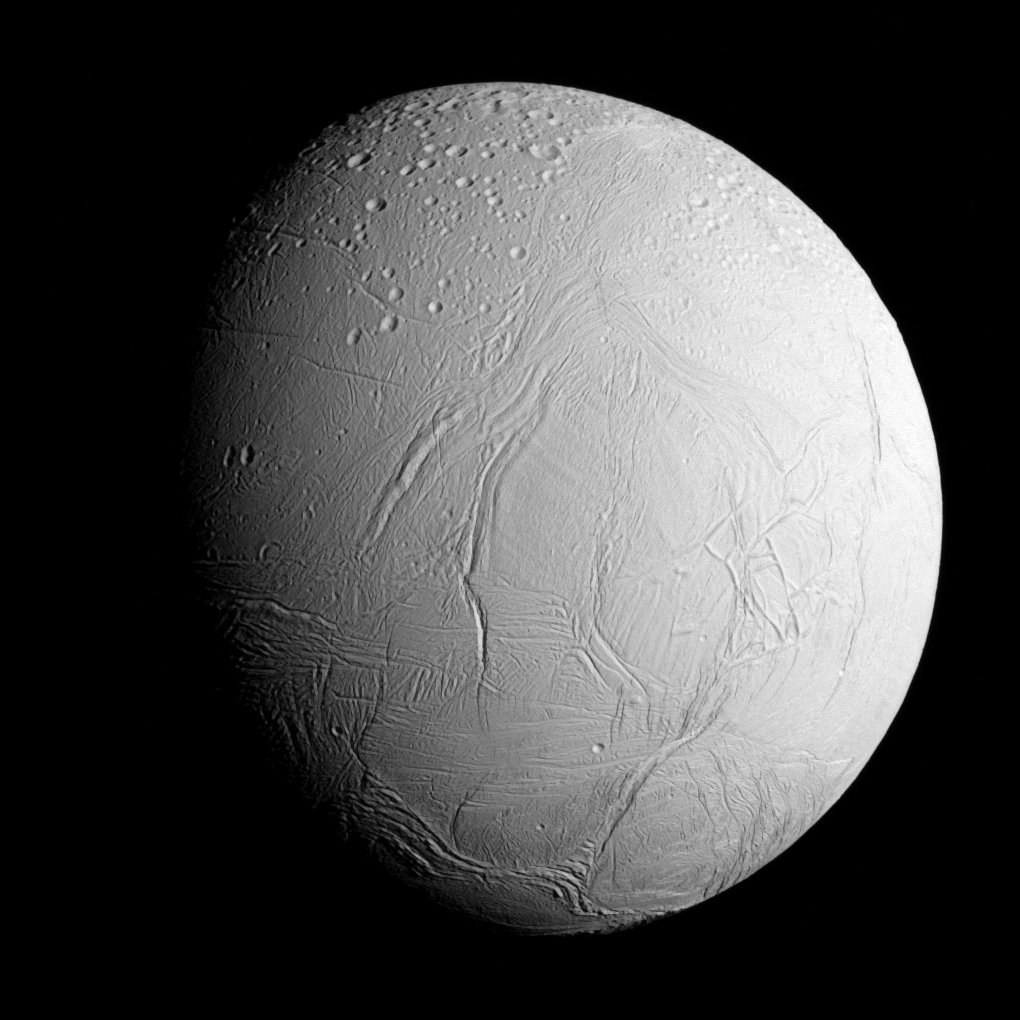

In the frozen reaches of the outer Solar System, where sunlight dwindles and temperatures plunge below imagination, a tiny moon glimmers with mystery. Barely 500 kilometers across—small enough to fit comfortably within the borders of Texas—Enceladus, one of Saturn’s most intriguing moons, has captured the imagination of scientists and dreamers alike. Despite its diminutive size, this icy world defies expectations. Beneath its frozen crust lies something astonishing: a vast, subsurface ocean that bursts through its surface in towering plumes of water and ice, spraying into space like cosmic geysers.

Discovered in 1789 by the British astronomer William Herschel, Enceladus was once just another speck among Saturn’s many moons. For nearly two centuries, it remained little more than a faint point of light—cold, distant, and silent. Then, in the early 21st century, the Cassini spacecraft changed everything. As it flew past Saturn and its moons, Cassini revealed that Enceladus was alive in a way no one expected. Geysers erupted from its south pole, feeding Saturn’s E-ring with icy particles. Beneath that frozen shell, evidence hinted at something even more profound: a liquid ocean of saltwater, heated by tidal forces and perhaps capable of supporting life.

Enceladus is a paradox of extremes—a world both frozen and fluid, lifeless and potentially alive, silent yet full of activity. It is a reminder that even in the coldest corners of the Solar System, nature finds ways to stir the waters of possibility.

Discovery and Early Observations

When William Herschel first observed Enceladus through his telescope in 1789, he could not have imagined the secrets it held. The telescope technology of his day could barely resolve it as a faint dot near the majestic planet Saturn. Enceladus’s small size and high reflectivity made it difficult to study, and for centuries it remained shrouded in mystery.

It was not until the 1980s that humanity first caught a closer glimpse of this icy moon. NASA’s Voyager missions, passing through the Saturnian system, sent back images that astonished astronomers. Unlike many of Saturn’s heavily cratered moons, parts of Enceladus appeared strangely smooth and bright, as if its surface had been renewed. There were ridges, fractures, and plains that hinted at geological activity—a surprising find for such a small, cold body.

Still, Voyager’s view was only a tantalizing preview. The true revelations came two decades later with the Cassini spacecraft, which arrived at Saturn in 2004. Equipped with a suite of cameras and instruments far more advanced than Voyager’s, Cassini made repeated flybys of Enceladus and transformed our understanding of what a “small moon” could be. What it found rewrote the rules of planetary science.

A World of Ice and Light

At first glance, Enceladus is dazzlingly bright—so bright, in fact, that it reflects almost all the sunlight that strikes it. Its surface albedo is among the highest in the Solar System, around 99 percent, due to the purity of its ice. To the naked eye, if you could approach it, Enceladus would shine like a diamond amid Saturn’s shadowy rings.

The surface is a frozen wilderness of contrasts. Some regions are ancient and scarred by craters, the relics of billions of years of bombardment. Others are young and remarkably smooth, etched with cracks, ridges, and grooves—evidence of tectonic reshaping. This diversity tells a story of renewal. While most small moons are dead and inert, Enceladus is dynamic. Its surface has been resurfaced again and again, suggesting that something beneath the ice is stirring.

Cassini’s infrared measurements revealed heat radiating from Enceladus’s south pole—a shock for a world so far from the Sun. The heat signatures lined up with long, linear fissures nicknamed the “tiger stripes,” each hundreds of kilometers long. From these stripes, plumes of vapor and ice shot into space, reaching heights of hundreds of kilometers. For the first time, scientists realized that Enceladus was not frozen solid—it was venting the contents of a hidden ocean.

The Tiger Stripes and the Cryovolcanic Plumes

The discovery of the plumes was a watershed moment in planetary exploration. Cassini’s cameras captured them in stunning detail: delicate jets of vaporized water, ice particles, and organic molecules erupting through fissures in the icy crust. These jets were not random—they emanated from specific fractures that crisscrossed the south polar region, glowing faintly with internal warmth.

Scientists named the major fractures after places in The Arabian Nights, such as Baghdad Sulcus and Damascus Sulcus. From these “tiger stripes,” material escaped at supersonic speeds, forming vast plumes that arced gracefully into space. Some of the ejected particles fell back onto the surface as fresh snow, keeping Enceladus bright and reflective, while others drifted outward to feed Saturn’s faint E-ring.

What drives these eruptions? The answer lies deep beneath the ice. Enceladus orbits Saturn in resonance with another moon, Dione. This gravitational relationship stretches and compresses Enceladus periodically, generating heat through tidal friction—much like bending a paperclip repeatedly until it warms. This internal heating prevents the moon’s subsurface ocean from freezing entirely and powers the spectacular geysers that pierce its crust.

The plumes were not only beautiful—they were scientifically priceless. Cassini flew directly through them multiple times, sampling their composition. What it found hinted at something extraordinary.

The Hidden Ocean Beneath the Ice

When Cassini analyzed the material in Enceladus’s plumes, it found water vapor, ice grains, carbon dioxide, methane, and ammonia—molecules that could only originate from a liquid reservoir beneath the surface. Later, as the data were refined, more complex organic compounds were detected, including hydrocarbons and amino acid precursors, the building blocks of life.

Further gravitational studies revealed subtle variations in the moon’s motion, suggesting that its outer shell was not rigidly connected to its core. These oscillations could only be explained if the icy crust floated atop a global ocean. The implications were stunning: a moon smaller than England held a subsurface sea beneath kilometers of ice, kept liquid by tidal forces from Saturn’s gravity.

This ocean is believed to be in contact with the rocky mantle below, allowing for chemical interactions similar to those at Earth’s deep-sea hydrothermal vents. On our planet, such vents teem with life, powered not by sunlight but by chemical energy. If similar processes occur within Enceladus, it could provide the conditions necessary for microbial life to arise and survive.

In this frozen world, far from the Sun, warmth and chemistry intertwine beneath an icy shell. Enceladus, it seems, is not a static body of ice—it is an active ocean world, a miniature planet with the essential ingredients for life.

The Chemistry of Life

The plume data provided a treasure trove for astrobiologists. Within the fine spray of ice particles, Cassini’s instruments detected not only simple molecules like water and carbon dioxide, but also hydrogen gas—a critical discovery. Hydrogen is a key indicator of hydrothermal activity, as it can form when water interacts with hot rock, releasing chemical energy.

On Earth, hydrothermal vents deep in the oceans are rich with such reactions. Microorganisms thrive there, feeding on hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and minerals, creating entire ecosystems independent of sunlight. The same chemistry could, in theory, sustain life on Enceladus.

In 2017, researchers confirmed that the hydrogen detected by Cassini likely originates from hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. This meant that within Enceladus’s dark, pressurized ocean, energy was available for microbial metabolism—a tantalizing possibility that pushes the boundaries of where life might exist.

Moreover, organic compounds identified in the plumes were not just simple molecules. Cassini detected complex carbon-bearing structures—potential precursors to amino acids and other biological macromolecules. Such chemistry implies that the ocean beneath Enceladus is not just water, but a dynamic, reactive environment capable of producing life’s essential ingredients.

The Heat Beneath the Ice

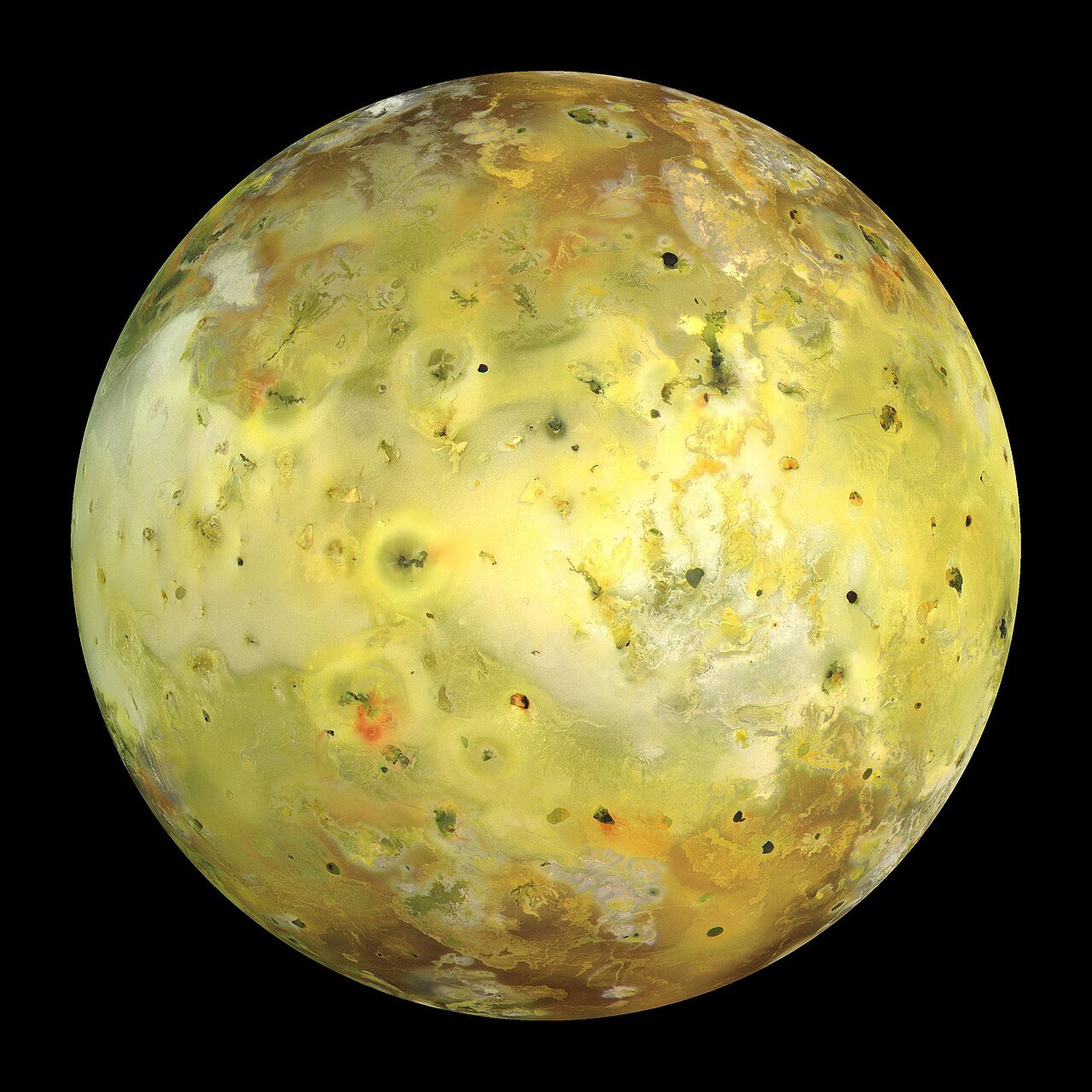

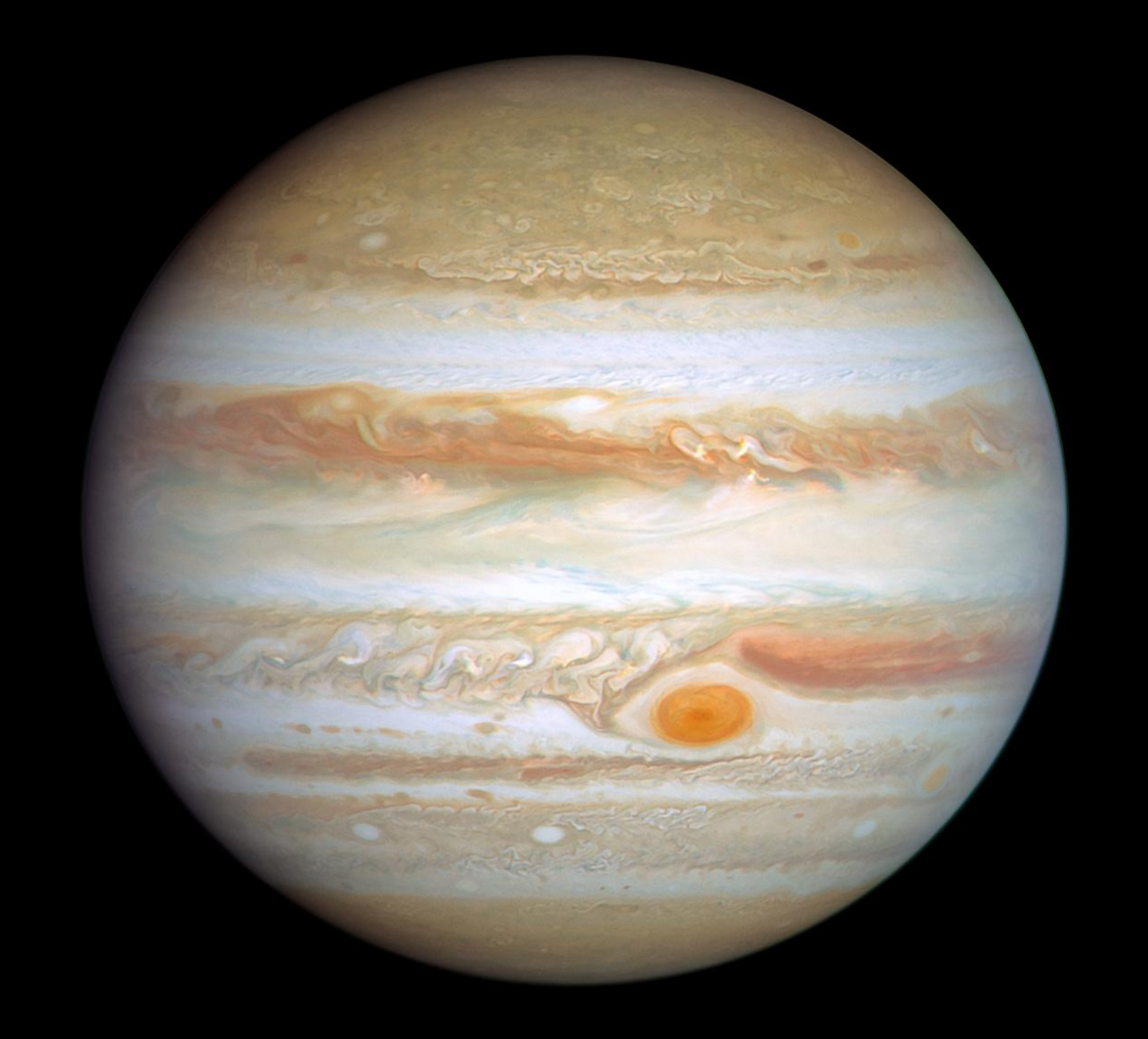

How can such a small moon maintain liquid water beneath its frozen crust? The answer lies in the interplay between gravity and motion. Enceladus’s orbit is slightly elliptical, and as it travels around Saturn, the planet’s immense gravity tugs on it unevenly. This constant flexing creates friction within the moon’s interior, generating heat—a process known as tidal heating.

This same mechanism drives volcanic activity on Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active world in the Solar System. But while Io’s energy escapes through fiery eruptions of molten rock, Enceladus channels its heat into maintaining a subsurface ocean beneath its ice. The heat is concentrated near the south pole, where the tiger stripes mark regions of ongoing flexing and cracking.

Measurements show that the south polar region emits far more heat than models predicted, suggesting that Enceladus’s interior is more active than once thought. The ice near the plumes may be only a few kilometers thick, thin enough for liquid water to reach the surface.

This delicate balance—between cold and warmth, between freezing and flowing—creates a dynamic system that has persisted for billions of years. Enceladus demonstrates that even in the outer Solar System, far from the Sun’s warmth, internal energy can sustain environments where life might flourish.

The Ocean’s Depths

Though Cassini’s mission ended in 2017, the data it gathered continue to reveal Enceladus’s secrets. Scientists now estimate that the ocean beneath the ice may be tens of kilometers deep, containing more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. It may be global, enveloping the entire moon beneath a thick crust of ice.

The interaction between the rocky core and the ocean likely plays a vital role in maintaining this system. Minerals leaching from the rock could supply nutrients, while hydrothermal vents release both heat and reactive chemicals. In essence, Enceladus may host a miniature version of Earth’s deep ocean ecosystems—minus the sunlight.

What we do not yet know is whether the ocean contains life. Cassini lacked the tools to detect microbes directly, but future missions could carry instruments capable of identifying biological molecules or even living cells within the plumes. If life does exist on Enceladus, it would represent a second genesis—a confirmation that biology can arise wherever the conditions are right, even in the cold darkness of space.

Feeding Saturn’s E-Ring

Enceladus does not exist in isolation. The particles ejected from its plumes form Saturn’s diffuse E-ring, a delicate halo of ice and dust that extends far into space. Cassini’s instruments traced the composition of the E-ring directly back to Enceladus, confirming that the moon continually replenishes it.

In this way, Enceladus is both sculptor and sustainer, contributing to the beauty of Saturn’s ring system. The icy grains from its plumes scatter sunlight, giving the E-ring its faint, ethereal glow. Some of these particles fall back onto the moon’s surface, refreshing it with fresh frost, while others drift outward, forming an ever-renewing cosmic bridge between Enceladus and Saturn.

This ongoing interaction between moon and planet is a kind of symbiosis—an elegant dance of matter and energy that binds Enceladus not just gravitationally, but aesthetically, to its parent world.

Cassini’s Legacy

The Cassini mission remains one of the most successful planetary explorations in history. Launched in 1997, it spent over thirteen years orbiting Saturn, studying its rings, atmosphere, and moons. But perhaps its most profound legacy lies with Enceladus.

Through a series of daring flybys—sometimes passing within just 50 kilometers of the surface—Cassini gathered direct evidence of Enceladus’s ocean, its chemical composition, and its active geology. It flew through the plumes repeatedly, “tasting” the spray of a hidden sea millions of kilometers away. Each encounter deepened our understanding and expanded our sense of wonder.

When the mission ended in 2017, Cassini was deliberately plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere to avoid contaminating moons like Enceladus that might harbor life. Its final moments were a fitting tribute to the spirit of discovery it embodied—a graceful descent into the planet it had studied so long, ensuring that the mysteries of Enceladus remained pure for future explorers.

The Search for Life

Among all the worlds in our Solar System, Enceladus now stands as one of the most promising candidates for extraterrestrial life. It possesses three essential ingredients: liquid water, organic chemistry, and energy. Its ocean may be salty, warm, and chemically active. The presence of molecular hydrogen suggests ongoing hydrothermal reactions—a key source of energy for life on Earth’s ocean floors.

If life exists there, it may resemble Earth’s extremophiles—microorganisms that thrive in harsh environments like hydrothermal vents, polar ice, or deep underground rocks. Such organisms rely not on sunlight, but on chemical gradients for energy. On Enceladus, they might dwell in the dark ocean, feeding on the same reactions that create hydrogen and methane.

The beauty of Enceladus’s plumes is that they offer a natural sampling system. Future spacecraft could fly through the geysers, collect material, and analyze it for biological signatures—no need to drill through kilometers of ice. This accessibility makes Enceladus a prime target for future missions aimed at answering one of humanity’s oldest questions: Are we alone?

Future Missions and Dreams

Several mission concepts have been proposed to return to Enceladus. NASA’s Enceladus Orbilander, for instance, envisions an orbiter that would study the moon in detail before landing near the active plumes. It would analyze surface material and search for signs of life in situ, effectively becoming a mobile laboratory.

Other ideas include flyby missions equipped with mass spectrometers and microscopes capable of detecting complex biomolecules, or even robotic submarines designed to one day explore the ocean itself. Each concept reflects a growing realization that Enceladus may hold the key to understanding life beyond Earth.

International collaboration will likely play a major role in this next chapter. Just as Cassini was a joint effort between NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency, future missions to Enceladus may unite scientists and engineers from around the world in a shared pursuit of discovery.

A Mirror of Earth

Enceladus is, in many ways, a reflection of our own planet—an echo of Earth’s early history preserved in ice. It reminds us that the ingredients for life are not confined to the narrow “habitable zone” around a star. Energy, chemistry, and water can create pockets of habitability even in the farthest reaches of space.

Its hidden ocean challenges our preconceptions about where life can exist. Once, we imagined that life required warmth and sunlight. Enceladus shows that darkness and cold are not barriers but stages upon which new forms of existence might emerge. Its hydrothermal vents could mirror those where life began on Earth billions of years ago, suggesting that the spark of biology might not be unique to our world.

In studying Enceladus, we are also studying ourselves—our origins, our fragility, and our place in the universe.

The Poetic Science of Enceladus

Science often speaks in the language of data and equations, but Enceladus invites poetry. It is a world where ice breathes, where oceans sing into the vacuum of space. Its plumes are both scientific phenomena and celestial art, transforming the cold mechanics of physics into something profoundly beautiful.

To watch Enceladus from orbit around Saturn would be to witness nature’s quiet defiance—the proof that even a tiny moon, dwarfed by its planet’s majesty, can hold within it an ocean, a heartbeat, perhaps even life. It embodies the cosmic truth that greatness is not measured by size, but by mystery.

Every plume that erupts from its surface is a whisper from the deep, a message from an unseen ocean inviting us to listen, to question, to dream.

The Cosmic Significance

Enceladus has changed our understanding of the universe. It has shown that worlds capable of supporting life may be far more common than once believed. If such a small, icy moon can sustain a liquid ocean and complex chemistry, then the conditions for life could exist on countless other moons and planets across the cosmos.

Its discovery expands the concept of habitability beyond the traditional view of Earth-like planets orbiting in a narrow band around their stars. Life, we now realize, may thrive in subsurface oceans beneath ice, fueled not by sunlight but by the warmth of internal tides and chemical reactions. The universe, once imagined as mostly barren, may in fact be teeming with hidden oceans and potential biomes.

Enceladus thus stands as both a scientific revelation and a philosophical reminder: that life’s possibilities are vast, and that the boundaries of the known are only beginnings.

The Eternal Fountain

As we look toward the future, Enceladus continues its silent dance around Saturn, spraying its ocean into the void. Each plume is a gesture of defiance against the cold, a statement that even the smallest worlds can hold vast secrets. Beneath its frozen shell lies an ocean that may have been stable for billions of years—a cradle of chemistry, perhaps of life, preserved in darkness.

Someday, humans or their machines will return to taste those waters again, to probe their mysteries, to listen for the faintest echoes of biology. And if we find even a single microbe, a single living cell beneath that ice, it will change everything. It will mean that life is not an accident but a universal phenomenon, a thread woven through the fabric of the cosmos.

Until then, Enceladus waits—tiny, brilliant, and eternal—a shimmering beacon in the shadow of Saturn, a world where oceans breathe into space, and where the question of life finds one of its most compelling echoes.

In the vast stillness of the Solar System, Enceladus whispers the same message to all who dare to listen: that in even the smallest and coldest corners of the universe, the spark of wonder endures.