Long before the rise of Rome, before Egypt’s pyramids gleamed in the sun, and centuries before Babylon’s gardens were ever dreamed of, there was Akkad. From the fertile plains of ancient Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers breathed life into the world’s first cities, the Akkadian Empire emerged as humanity’s first great empire—a civilization that changed the course of history forever.

It was here, in the cradle of civilization, that humans first learned to write, to measure time, to govern through law, and to dream of power beyond their city walls. But it was the Akkadians who transformed those dreams into reality. They were the first to bind many lands and peoples under one ruler, one language, and one vision. Their empire marked the beginning of the age of kings who ruled not just a city, but a world.

At the heart of this story stands a man whose legend would echo through millennia: Sargon of Akkad. A commoner turned conqueror, Sargon was the architect of an empire that united Mesopotamia for the first time in history. His reign—brilliant, brutal, and revolutionary—lit the torch of empire that countless rulers would later try to grasp.

The World Before Akkad

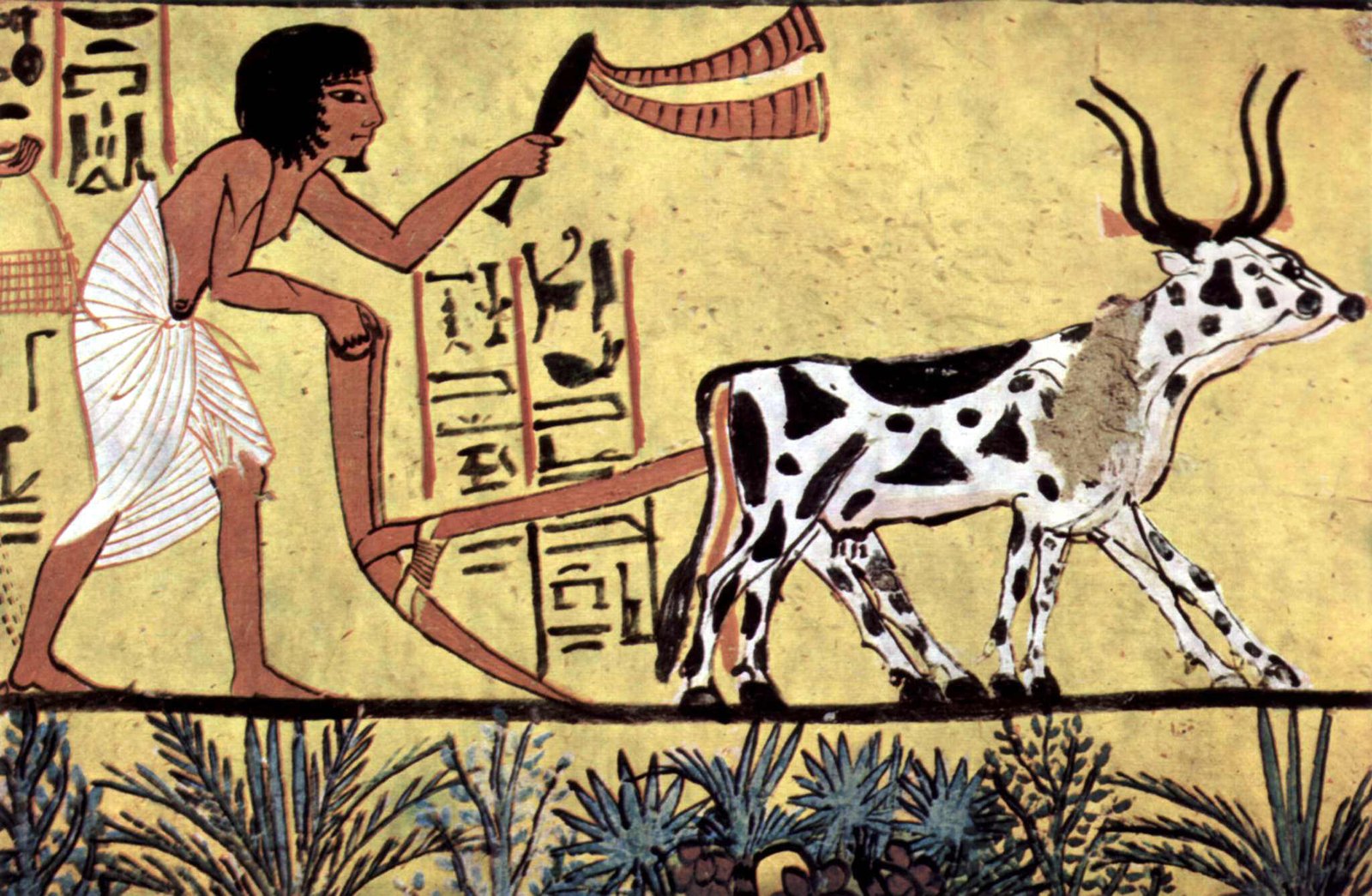

To understand the rise of the Akkadian Empire, one must first step into the world it was born from—Sumer, the land of city-states. In the early third millennium BCE, the plains of southern Mesopotamia were dotted with independent cities such as Ur, Uruk, Lagash, and Kish. Each city was a world unto itself, with its own king, its own gods, and its own ambitions.

These Sumerian city-states were centers of innovation. They built monumental temples called ziggurats that reached toward the heavens. They developed cuneiform, the first known writing system, inscribing their language on clay tablets that would survive thousands of years. They organized irrigation systems, recorded laws, and composed hymns and myths that still speak to us today.

Yet, for all their brilliance, the Sumerians were divided. Rivalries and wars between city-states were constant. Their armies clashed for control of fertile fields and sacred water channels. No single ruler could hold them all in check for long. The idea of a united Mesopotamia—a single ruler commanding all the lands between the rivers—was still a dream.

That dream would soon become reality under a man who began his life not as a prince, but as an outcast.

The Rise of Sargon the Great

The story of Sargon is one of history’s most extraordinary tales—a journey from obscurity to greatness that rivals any epic. According to legend, he was born the illegitimate son of a priestess and set adrift as an infant in a basket on the Euphrates River. Rescued and raised by a humble gardener, Sargon grew up far from the centers of power. But destiny had chosen him for something greater.

As a young man, Sargon entered the service of Ur-Zababa, the king of Kish, one of Sumer’s most powerful city-states. There, his intelligence and ambition quickly set him apart. Eventually, he seized power for himself, overthrowing his master and proclaiming himself ruler of Kish. But Sargon’s hunger could not be satisfied with one city. He dreamed of conquest—of uniting all Mesopotamia under his rule.

What followed was a campaign unlike anything the ancient world had ever seen. Sargon marched south, defeating one Sumerian city after another. Uruk, Ur, Lagash, and Umma all fell to his armies. He then turned northward, conquering Mari and Ebla, extending his dominion beyond the fertile plains into Syria and the Levant.

In time, Sargon claimed control of an empire stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea—a realm so vast that no one before him had ever imagined ruling it. He called himself “King of Akkad, King of Sumer, King of the Four Quarters of the World.”

The Birth of Akkad

The capital of this new empire was Akkad—also known as Agade—a city whose exact location remains lost to history. Though archaeologists have searched for it for more than a century, Akkad has never been definitively found. Yet from ancient texts, we know that it was magnificent, a center of administration, trade, and art.

Akkad became the heart of a new civilization that blended the cultures of north and south. The Akkadians adopted much from the Sumerians—their gods, their script, their temple architecture—but they infused it with their own Semitic language and worldview. Akkadian, a language related to Hebrew and Arabic, soon replaced Sumerian as the tongue of government and literature.

This fusion of Sumerian and Akkadian cultures produced something entirely new: the world’s first imperial civilization. It was no longer a collection of warring city-states but a unified state with centralized power, a professional army, and a bureaucracy that reached across hundreds of miles.

For the first time in history, humanity had created not just a kingdom, but an empire.

The Machinery of Power

Sargon’s success was no accident. He understood that conquest alone was not enough; to hold an empire together required systems of administration and control. To achieve this, he built an infrastructure of governance that would become the model for centuries to come.

He placed trusted officials—often his own family members—in charge of conquered cities. These governors, or ensi, were loyal to him above all others. They collected taxes, managed resources, and enforced Akkadian authority. To ensure communication across his vast territory, Sargon established a network of roads and messengers—a primitive but effective imperial postal system.

Sargon also maintained a standing army, a professional force that could move swiftly to suppress rebellion or extend the empire’s borders. This army was well-trained, disciplined, and loyal to the king himself rather than to individual city-states.

Religion, too, became a tool of unity. The Akkadians promoted the worship of their chief deity, Ishtar (Inanna in Sumerian), the goddess of love and war. Sargon claimed divine favor, portraying himself not just as a king but as a chosen instrument of the gods. Through this blend of power, organization, and ideology, he transformed Mesopotamia from a patchwork of rivals into a single political entity.

The Golden Age of Akkad

Under Sargon and his successors, the Akkadian Empire entered a golden age. Trade flourished across the empire, linking distant regions in a network of exchange that spanned from Anatolia to the Persian Gulf. Goods such as copper, tin, silver, lapis lazuli, and grain flowed along these routes, enriching the cities of Akkad.

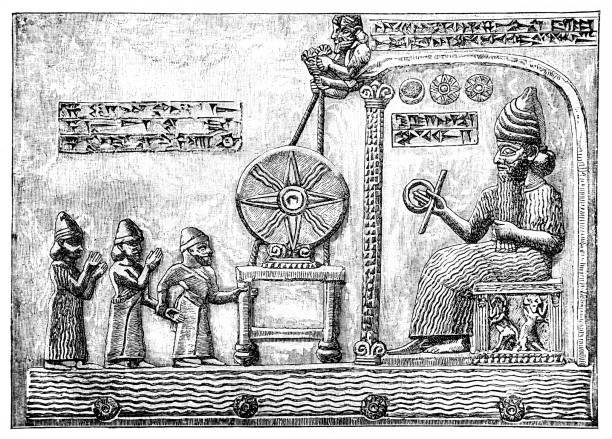

Cultural and artistic life thrived as well. The Akkadians developed a distinct artistic style—more dynamic and expressive than their Sumerian predecessors. Their sculptures depicted kings and gods with lifelike realism and power. One of the most famous examples is the bronze head of an Akkadian ruler, possibly Sargon himself, found in Nineveh. The piece, with its intricate detailing and solemn expression, captures both the authority and humanity of early imperial power.

Literature also blossomed. The Akkadians adapted Sumerian cuneiform for their own language, producing texts that ranged from administrative records to epic poetry. These writings preserved myths, hymns, and historical inscriptions that still survive on clay tablets today.

Perhaps most importantly, the empire fostered a sense of shared identity. People from distant cities, once enemies, now thought of themselves as subjects of the same ruler. The Akkadian dream of unity—of one civilization under a single crown—had become reality.

The Reign of Naram-Sin: The God-King of Akkad

After Sargon’s death, his sons Rimush and Manishtushu inherited the throne, continuing his policies and expanding his empire. But it was Sargon’s grandson, Naram-Sin, who would take Akkad to its zenith—and to its downfall.

Naram-Sin ruled with ambition equal to his grandfather’s. His reign, around 2254–2218 BCE, marked the height of Akkadian power. He called himself “King of the Four Quarters” and, more audaciously, declared himself divine—the living god of Akkad. For the first time in recorded history, a Mesopotamian ruler claimed divinity during his lifetime.

This act shocked the traditional priesthood, who saw it as sacrilege. Yet Naram-Sin used divine kingship to legitimize his authority and unify his vast realm. His empire stretched from the Mediterranean to the Zagros Mountains, encompassing countless peoples and cultures.

The famous Victory Stele of Naram-Sin immortalizes his triumphs. The carving shows the king towering above his enemies, trampling them beneath his feet, wearing a horned helmet—the symbol of divinity. It is not just a record of conquest, but a declaration of cosmic order: the king as the axis between heaven and earth.

Under Naram-Sin, the empire reached its cultural and political peak. Yet even as he built monuments to his glory, forces of chaos gathered at the edges of his realm.

The Fall of the First Empire

Every empire has its shadow. For Akkad, it came in the form of drought, rebellion, and invasion.

Archaeological evidence suggests that around 2200 BCE, a massive climate event struck the Near East. Rainfall declined sharply, and the once-fertile lands of Mesopotamia turned to dust. Crops failed, rivers shrank, and famine spread. The great irrigation systems could no longer sustain the population.

As the land withered, so did the empire. Subject peoples, weary of Akkadian dominance, began to rebel. In the north, the Gutians—a mountain people from the Zagros region—invaded, plundering cities and disrupting trade. The once-mighty army of Akkad could not withstand the combined weight of rebellion and environmental disaster.

Naram-Sin’s successors struggled to hold the empire together, but within a few decades, Akkad fell into ruin. Its cities were abandoned or destroyed. The empire that had once united the known world vanished into legend.

Later generations looked back on its fall with awe and fear. The Sumerian Curse of Akkad, a poetic lament written centuries later, describes how the gods themselves turned against Sargon’s descendants, bringing drought and chaos as punishment for human pride.

The Legacy of Akkad

Though the Akkadian Empire fell, its legacy endured for millennia. It laid the foundations for every empire that followed in Mesopotamia and beyond. The concept of a centralized state, a professional army, and a divine ruler became the blueprint for future civilizations—from Babylon to Persia, from Rome to modern nation-states.

Culturally, Akkadian replaced Sumerian as the dominant language of the region. It became the lingua franca of diplomacy, trade, and scholarship across the ancient Near East for over a thousand years. Even after Akkad’s fall, scribes continued to write in Akkadian long into the time of Hammurabi and beyond.

The very idea of kingship itself changed because of Sargon and his descendants. No longer was a king merely the ruler of one city; he was the shepherd of peoples, the servant of the gods, and the master of an empire.

In this sense, the Akkadian Empire never truly died. Its spirit lived on in the empires that followed—the Babylonians, the Assyrians, the Persians—all heirs to the dream first kindled in the dust of Mesopotamia.

Rediscovering Akkad

For thousands of years, Akkad was a name half-remembered in myths and chronicles. Its location was lost, its monuments buried beneath sand and time. Only in the nineteenth century, with the birth of modern archaeology, did the Akkadians rise again—this time from the earth itself.

In the ruins of Mesopotamian cities, scholars unearthed clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform texts that spoke of Sargon, Naram-Sin, and the empire of Akkad. As these tablets were deciphered, a forgotten chapter of human history came to light.

The discovery was revolutionary. It revealed that the story of empire—of ambition, unity, and downfall—had begun not in Greece or Rome, but thousands of years earlier, in the land between two rivers. Akkad was not just a historical curiosity; it was the prototype for civilization as we know it.

Today, museums around the world display the relics of Akkad—inscriptions, statues, and artifacts that whisper of the first great empire. Though the city of Akkad itself remains undiscovered, every fragment we uncover brings us closer to its memory.

The Legacy Written in Clay and Fire

The Akkadians did more than build an empire—they built the idea of empire. They showed humanity what was possible when organization, vision, and force combined under a single will. But they also demonstrated the cost of power—the fragility of greatness when confronted by nature and time.

Their achievements live on not only in history but in the symbols of civilization itself. Writing, administration, taxation, trade, diplomacy—all were refined in the crucible of Akkadian rule. Even their myths left echoes that shaped later cultures. The tales of mighty kings, of floods and divine wrath, of cities cursed by gods—all trace their origins to the Akkadian age.

In many ways, the Akkadian Empire marks the birth of human ambition on a global scale. It was the first time we reached beyond the boundaries of city and tribe to create something universal.

The Eternal Lesson of Akkad

The story of the Akkadian Empire is not merely ancient history—it is a mirror of humanity’s eternal struggle between creation and destruction, unity and chaos. It tells of how power can build civilizations and also how it can unravel them. It reminds us that every empire, no matter how vast, stands on fragile foundations: the favor of nature, the loyalty of people, and the wisdom of those who rule.

When Sargon declared himself “King of the Four Quarters of the World,” he gave humanity a new dream—the dream of empire. And though his city has vanished and his dynasty long crumbled to dust, that dream endures in every age that seeks to unify, to expand, to reach for greatness.

The Akkadian Empire was not just the first empire; it was the beginning of a pattern that would repeat throughout history. It was the first heartbeat of human civilization as we know it—the first time our species looked beyond the horizon and said: All of this can be one.

And though the winds of time have buried its stones, the memory of Akkad still burns, quietly but eternally, in the story of who we are.

For as long as human beings build, rule, and dream of unity, the spirit of Sargon and his empire—the first great empire in human history—will never truly fade.