In the heart of the Mesopotamian plain—between the mighty rivers Tigris and Euphrates—there once rose a city so magnificent, so radiant with power and culture, that it became the symbol of human achievement and divine ambition. Its name was Babylon. To its people, it was the center of the universe, the gate between gods and men. To those who came after, it became a legend—a place of glory, mystery, and pride, both celebrated and condemned through millennia.

Babylon was not merely a city; it was the heartbeat of an empire and the embodiment of an idea—that humanity could shape the world through intellect, art, and will. Its towering ziggurats pierced the heavens, its scholars mapped the stars, and its kings dreamed of immortality. For centuries, Babylon ruled not just through conquest but through culture, leaving an imprint on history that no empire since has fully erased.

But as with all empires, Babylon’s light eventually dimmed. Its walls crumbled, its gods fell silent, and its people scattered into the pages of history. Yet even in ruin, Babylon remains alive—etched into language, religion, and the collective imagination of humankind. To understand Babylon is to understand the origins of civilization itself and the eternal human desire to reach beyond the limits of the possible.

The Birth of a Civilization Between Two Rivers

Long before Babylon became the jewel of the ancient world, the land of Mesopotamia was already a cradle of civilization. Between the fertile waters of the Tigris and Euphrates, early peoples learned to harness nature’s gifts. They built canals, grew crops, and founded the first cities—Uruk, Ur, Kish, and Lagash—thousands of years before Rome or Athens ever existed.

From this landscape of innovation emerged Babylon, a settlement that began humbly around 2300 BCE. At first, it was a small, unremarkable town. But its location was a blessing. It sat near vital trade routes connecting Sumer in the south to Akkad in the north and the distant lands beyond. Goods, ideas, and peoples flowed through it like lifeblood, and over centuries, Babylon grew from a provincial outpost into a thriving metropolis.

Its early rulers were vassals of more powerful kings, until one man changed everything: Hammurabi.

Hammurabi: The Lawgiver King

Around 1792 BCE, Hammurabi ascended the throne of Babylon and transformed it into the most powerful kingdom in Mesopotamia. He was not merely a conqueror; he was a statesman, an organizer, and a visionary. Through diplomacy, warfare, and shrewd governance, he unified the scattered city-states of the region into a single empire.

But Hammurabi’s greatest legacy was not his empire—it was his code. The Code of Hammurabi, carved into a towering black stele of basalt, stands as one of the earliest and most influential legal systems in human history. “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”—the principle of justice through proportional punishment—echoes from its inscriptions.

The laws addressed everything from trade and property to family and crime. They established fairness, accountability, and the idea that even kings were bound by law. At a time when might often made right, Hammurabi’s code was revolutionary.

The stele’s top depicts the king receiving the laws from Shamash, the sun god of justice—a powerful image that proclaimed Hammurabi’s rule as divinely ordained. This fusion of law, divinity, and authority became a hallmark of Babylonian civilization, one that influenced legal thought for millennia.

The Splendor of the City

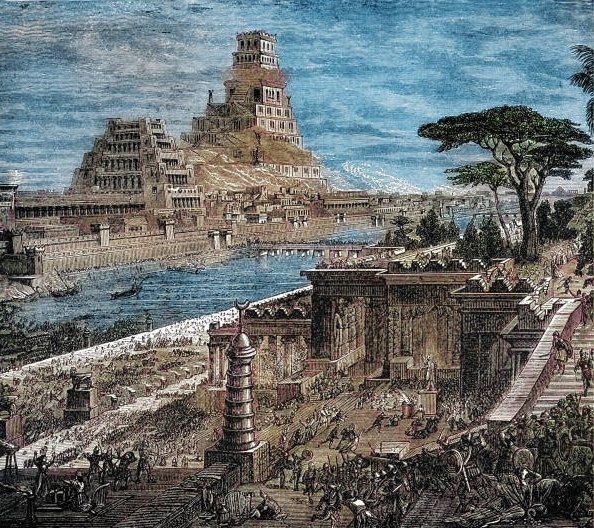

As centuries passed, Babylon grew into a city of breathtaking grandeur. It was a marvel of architecture, engineering, and urban planning—a city built not only for power but for beauty. Ancient writers spoke of its massive double walls, its broad processional avenues, and its gates adorned with glazed blue bricks and sacred beasts.

The most famous of these was the Ishtar Gate, constructed under King Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE. It was a masterpiece of craftsmanship, covered in shimmering cobalt tiles and decorated with rows of dragons, bulls, and lions—symbols of divine power. The gate led to the Processional Way, a broad street lined with temples and statues that culminated in the grand ziggurat and the temple of Marduk, Babylon’s chief deity.

At the heart of the city rose the Etemenanki, the “House of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth”—a massive ziggurat that may have inspired the biblical story of the Tower of Babel. To the Babylonians, it was the axis of the universe, the bridge between heaven and earth.

Babylon’s walls were said to be so thick that chariots could race upon them, and its canals gleamed with water drawn from the Euphrates. The city was alive with merchants, priests, scribes, astronomers, and artisans. It was a place where gold glittered, languages mingled, and ideas flourished.

The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar II: Babylon’s Golden Age

The name Nebuchadnezzar II (reigned 605–562 BCE) stands at the pinnacle of Babylon’s history. He was a warrior, builder, and visionary whose reign marked the city’s zenith. Under his leadership, Babylon became not just the capital of an empire but the wonder of the ancient world.

Nebuchadnezzar expanded Babylon’s borders through conquest, defeating the Egyptians and capturing Jerusalem. But he was also a master builder, transforming his capital into a city of splendor that astonished all who beheld it. He restored temples, constructed palaces, and reinforced the mighty city walls.

It was during his reign that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were said to have been built—a terraced paradise of trees, flowers, and flowing water. Ancient writers described them as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, a marvel of engineering and beauty unlike anything on Earth.

According to legend, Nebuchadnezzar built the gardens for his Median wife, Amytis, who missed the green hills of her homeland. Though the exact location and even existence of the gardens remain debated, they symbolize the grandeur and romantic spirit of Babylon’s golden age.

Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon was more than a city of beauty—it was a hub of intellect. Scholars studied mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and literature. The Babylonians charted the stars, predicted eclipses, and divided time into hours and minutes—a system we still use today. They recorded their discoveries on clay tablets that survive to this day, offering glimpses into their extraordinary minds.

Marduk: The God of Gods

Religion lay at the center of Babylonian life. Every festival, every law, every stone of the city was tied to its gods. Chief among them was Marduk, the supreme deity who rose from local patron to cosmic ruler. His temple, Esagila, was the spiritual heart of Babylon, and his annual New Year festival reaffirmed the bond between god, king, and people.

The Enuma Elish, Babylon’s creation epic, tells how Marduk defeated the chaos-dragon Tiamat and created the world from her divided body. He brought order from chaos, light from darkness. The story was not only mythology—it was a statement of cosmic and political authority. Just as Marduk ruled the heavens, Babylon ruled the earth.

During the New Year festival, the statue of Marduk was carried through the city in procession, accompanied by music, offerings, and rituals. The king would humble himself before the god, symbolically renewing his right to rule.

In Babylon, religion was not separate from daily life—it was the rhythm of existence itself. Every home had its household gods, every street its protective spirits. The people saw their city as a reflection of the divine order, its walls mirroring the cosmic balance that Marduk had forged from chaos.

The Tower of Babel and the Language of Heaven

Few stories capture the imagination like that of the Tower of Babel. In the Book of Genesis, humanity, united by a single language, sought to build a tower “that reaches to the heavens.” Angered by their pride, God scattered them and confused their tongues.

Many scholars believe this tale was inspired by the ziggurat of Babylon—the Etemenanki. Rising in seven tiers toward the sky, it embodied humanity’s ambition to reach the divine. To the Babylonians, it was a sacred mountain connecting earth and heaven. To later writers, it symbolized arrogance and divine punishment.

The story of Babel echoes the tension between human aspiration and humility, between creativity and hubris. It reminds us that Babylon was both admired and feared—a symbol of greatness and of the peril of overreaching power.

In its own time, however, Babylon’s multilingual, multicultural nature was a source of pride, not shame. The city was a melting pot of peoples from across the ancient world, where merchants from distant lands mingled in the markets and scholars exchanged ideas in the temples. It was the first true cosmopolis—a city of humanity.

The Fall to the Persians

But no empire lasts forever. After Nebuchadnezzar’s death, Babylon’s power began to wane. Internal strife, weak rulers, and external threats eroded its stability. The great empire that had once ruled from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean began to crumble.

In 539 BCE, a new power rose from the east—the Persian Empire, under the leadership of Cyrus the Great. Unlike the brutal conquests that had marked earlier empires, Cyrus’s approach was strategic and pragmatic. When his armies reached Babylon, they entered the city without battle. According to records, the Babylonians opened their gates willingly, disillusioned with their own king.

Cyrus respected Babylon’s traditions. He restored temples, honored Marduk, and allowed exiled peoples—including the Jews—to return to their homelands. For a time, Babylon continued to flourish as a cultural and administrative center under Persian rule. But its independence was gone. The age of Babylonian dominance had ended.

The Shadow of Alexander the Great

Nearly two centuries later, Babylon found itself at the center of yet another empire—that of Alexander the Great. When Alexander defeated the Persians, he marched triumphantly into Babylon in 331 BCE. To him, it was a city of myth and majesty, a fitting capital for his dream of a united world.

He ordered the restoration of Marduk’s temple and made plans to make Babylon his imperial seat. But fate intervened. In 323 BCE, Alexander fell ill in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar and died at the age of 32. His death marked not only the end of his empire but the symbolic end of Babylon’s role as the heart of civilization.

Over the following centuries, Babylon declined. The Euphrates shifted its course, trade routes changed, and new cities rose. The once-great metropolis slowly turned to dust. By the first century CE, when travelers visited its ruins, they found only mounds and broken walls where gods and kings had once walked.

Babylon in Memory and Myth

Though the physical city fell, Babylon lived on in human memory. In the Bible, it became a symbol of sin, pride, and divine judgment—the “Whore of Babylon,” the city of corruption and arrogance. In later centuries, the name “Babylon” came to represent decadence, tyranny, and moral decay.

Yet even as it was demonized, Babylon was also idealized. For historians and scholars, it remained a wonder of the ancient world. Greek writers like Herodotus described its massive walls and majestic temples, though often with exaggeration. For archaeologists of the modern era, it became a site of fascination and rediscovery.

When European explorers began excavating the mounds of Mesopotamia in the 19th century, they uncovered the reality behind the legend—cuneiform tablets, palace foundations, and the remnants of the Ishtar Gate. The lost city began to speak again, not in myth, but in history.

Babylon’s rediscovery revealed a civilization of extraordinary sophistication. Its people had developed one of the earliest writing systems, cuneiform, pressing wedge-shaped marks into clay tablets. They recorded laws, poetry, astronomy, and trade. They invented place-value notation and used a base-60 system, giving us the 60 minutes in an hour and 360 degrees in a circle.

Babylon was not just the city that ruled the world—it was the city that shaped it.

The Legacy of Babylonian Science and Thought

Babylon’s intellectual achievements were as monumental as its architecture. Its priests were astronomers, meticulously observing the movements of the heavens. They charted the paths of planets, predicted eclipses, and laid the foundations of astrology—an attempt to read divine will through the stars.

Mathematics, too, flourished in Babylon. Their sexagesimal (base-60) system was extraordinarily practical for fractions and angular measurements, and it endures in our timekeeping and geometry. Babylonian mathematicians could calculate square roots, solve quadratic equations, and estimate the value of π with remarkable accuracy.

They also advanced medicine, cataloging diseases and treatments on clay tablets. Though rooted in spiritual beliefs, their observations were systematic and empirical. In literature, they produced hymns, epics, and wisdom texts that rival the works of ancient Greece in depth and poetry.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, preserved in Babylonian libraries, is humanity’s oldest epic—a story of friendship, loss, and the quest for immortality. It captures the timeless human struggle against fate, echoing across 4,000 years to our own age.

Babylon and the Human Story

Babylon’s greatness was not only in its power but in its humanity. It was a place where the earliest dreams of order, justice, and knowledge took form. Its rise and fall mirror the cycles of civilization—the ascent to brilliance, the intoxication of success, and the inevitable descent into ruin.

Yet, perhaps Babylon never truly fell. It survives in our language (“Babble” derives from Babel), in our calendars, in our myths, and in our cities. Every metropolis that strives for greatness carries a spark of Babylon in its ambition.

The story of Babylon is the story of humanity itself—the yearning to build, to rule, to understand, and to defy the gods. It is the story of our eternal dance between creation and destruction.

Rediscovering Babylon Today

Today, the ruins of Babylon lie near modern-day Hillah in Iraq. Visitors can walk through reconstructed gates and walls, imagining the city as it once stood. The Ishtar Gate, now restored in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, still gleams with the same deep blue that once dazzled travelers thousands of years ago.

Archaeologists continue to study the site, unearthing clues about daily life—pottery, tablets, tools, and inscriptions. Each discovery brings us closer to the people who lived there: merchants selling goods by the river, priests performing rituals under the starlit sky, scribes etching symbols that would outlive empires.

Despite wars and time, Babylon endures—not just as ruins, but as an idea. It stands for humanity’s boundless creativity, for our longing to touch the divine, and for the consequences of our ambition.

The Eternal City in Spirit

Babylon’s tale did not end in ashes; it transformed into legend. It reminds us that greatness and downfall are inseparable twins—that every civilization is both a builder of wonders and a bearer of warnings.

To stand among the ruins of Babylon is to feel time collapse—to hear the echoes of markets, the chants of priests, the clash of armies, and the dreams of kings. The dust of its streets once carried the footsteps of people who believed they stood at the very center of the world. And in a sense, they did.

The spirit of Babylon still moves within us—in every city skyline, every law, every attempt to understand the stars. It lives in our desire to rise higher, to know more, to build lasting monuments of stone or thought.

For all its pride and tragedy, Babylon remains a testament to what humanity can achieve—and to what it must guard against. It was the city that ruled the world, yes, but more profoundly, it was the city that revealed what it means to be human: powerful, curious, flawed, and forever reaching toward the heavens.

In the burning sands of Mesopotamia, Babylon once shone like a second sun. And though its walls have fallen, its light endures—in memory, in myth, and in the eternal dream of civilization itself.