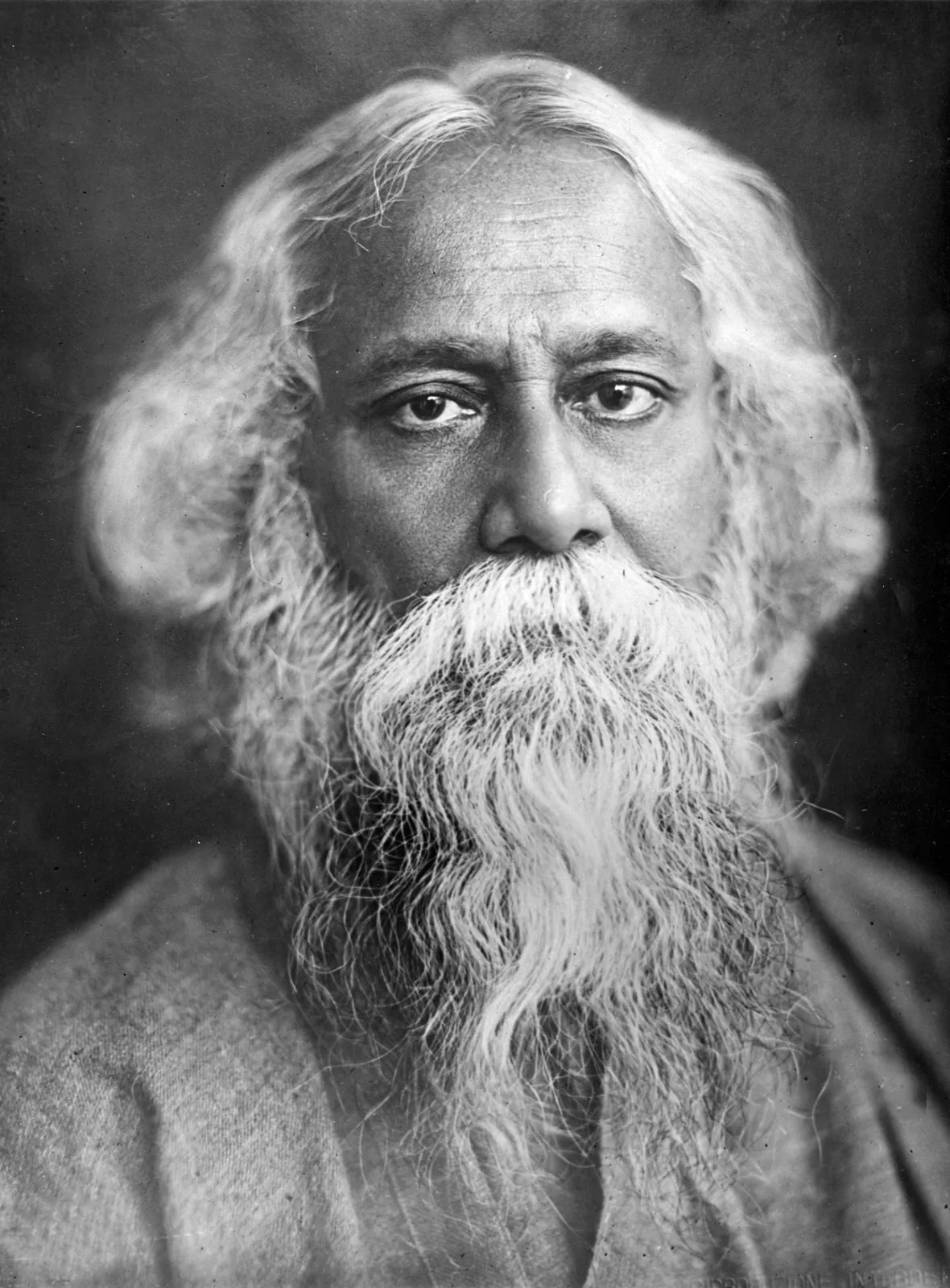

Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) was an Indian poet, writer, philosopher, and polymath who reshaped Bengali literature and music, as well as Indian art, with his deeply expressive and innovative works. Born in Calcutta (now Kolkata) into a prominent family, Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913 for his book of poems, Gitanjali (“Song Offerings”). His work transcended borders, blending the spiritual and the humane, often exploring themes of identity, freedom, and nature. Tagore was also a social reformer and educationist, founding the Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, which became a global center for learning. A versatile artist, he composed India’s national anthem, “Jana Gana Mana,” and was instrumental in the Indian Renaissance, advocating for cultural and intellectual self-reliance. Tagore’s legacy as a literary giant and a visionary thinker continues to inspire generations worldwide.

Early Life (1861–1883)

Rabindranath Tagore, also known as Gurudev, was born on May 7, 1861, in the Jorasanko mansion in Kolkata, India. He was born into the illustrious Tagore family, a prominent and influential family in Bengal with a rich cultural heritage. His father, Debendranath Tagore, was a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, a religious and social reform movement, while his mother, Sarada Devi, was a devout homemaker. Rabindranath was the youngest of thirteen children, and his upbringing was immersed in literature, music, and art, making the environment ideal for nurturing his creative instincts.

Rabindranath’s early education was unconventional. He did not attend formal school for a long period, as his father believed that formal education would stifle his creativity. Instead, he was tutored at home, which allowed him to explore a variety of subjects at his own pace. He was introduced to the works of classical Sanskrit literature, Bengali folk traditions, and Western literary traditions. His father also took him on a tour of India in 1873, during which he developed a deep connection with the land and its people, which would later influence his work.

In 1878, at the age of 17, Tagore was sent to England to study law, as his family hoped he would follow in his father’s footsteps. However, Rabindranath was more interested in literature and music. During his time in England, he was exposed to the works of Shakespeare, which had a profound impact on him. Although he did not complete his formal education, his time in England broadened his horizons and deepened his appreciation for Western literature.

Upon returning to India in 1880, Tagore began to engage more deeply with Bengali literature. He started writing poetry at a young age, and by the time he returned from England, he had already published several works. His early poetry was characterized by its romanticism and lyrical beauty, reflecting his deep connection to nature and his emotional sensitivity. His first major work, “Sandhya Sangit” (Evening Songs), published in 1882, marked the beginning of his journey as a poet and established him as a significant literary figure in Bengal.

During this period, Tagore also became increasingly involved in the cultural and social life of Bengal. He began to experiment with different forms of writing, including essays, short stories, and plays. His early stories, such as “Bhikharini” (The Beggar Woman) and “Kabuliwala,” are considered classics of Bengali literature. These stories are marked by their simplicity, emotional depth, and keen observation of human nature.

Tagore’s early life was also marked by personal challenges and tragedies. He lost his mother at a young age, and later, his wife Mrinalini Devi, whom he married in 1883 when she was just 10 years old. Despite these personal losses, Tagore continued to write prolifically, finding solace in his creative pursuits. His experiences of love, loss, and longing deeply influenced his work, giving it a profound emotional resonance.

In the early 1880s, Tagore began to develop his unique philosophical ideas, which would later become central to his work. He was deeply influenced by the Upanishads, the ancient Indian philosophical texts, and by the teachings of his father, Debendranath. Tagore’s philosophy emphasized the unity of all existence, the importance of self-realization, and the need for a harmonious relationship between the individual and the universe. These ideas would later find expression in his poetry, essays, and educational endeavors.

By the end of this period, Rabindranath Tagore had already established himself as a significant figure in Bengali literature. His early works laid the foundation for his later achievements and reflected the diverse influences that shaped his worldview. As he continued to evolve as a writer and thinker, Tagore would go on to make groundbreaking contributions to literature, art, and philosophy, not only in India but also on the global stage.

Literary Career and Philosophical Evolution (1883–1901)

The period between 1883 and 1901 was a time of profound growth and transformation for Rabindranath Tagore. It was during these years that he matured as a writer and thinker, refining his literary style and deepening his philosophical insights. This period also marked his increasing involvement in social and educational reforms, which would become a significant aspect of his legacy.

After his marriage to Mrinalini Devi in 1883, Tagore moved to Shelidah, a family estate in present-day Bangladesh, where he took charge of managing the family’s zamindari (estate). This move brought him closer to rural Bengal, and the experiences he gained there deeply influenced his literary work. The natural beauty of the countryside, the simple lives of the villagers, and the social inequalities he witnessed became central themes in his writings.

One of the most significant works of this period is his collection of poems titled “Manasi” (The Ideal One), published in 1890. In “Manasi,” Tagore’s poetic voice matured, reflecting a more complex understanding of human emotions and a deeper engagement with philosophical questions. The poems in this collection explore themes of love, longing, and the relationship between the individual and the universe. The influence of the Upanishads is evident in his exploration of the unity of all existence and the divine presence in nature.

Tagore’s literary output during these years was prolific. He wrote a number of short stories, essays, and plays that explored the social, cultural, and political issues of his time. His short stories, in particular, are considered some of the finest in Bengali literature. Works such as “Chhuti” (The Homecoming), “Postmaster,” and “Kabuliwala” are marked by their deep humanism, empathy for the marginalized, and subtle critique of social norms. These stories reveal Tagore’s keen observation of human nature and his ability to convey complex emotions with simplicity and grace.

In addition to his literary pursuits, Tagore became increasingly involved in social and educational reforms during this period. He believed that education should be holistic, nurturing the physical, intellectual, and spiritual development of individuals. In 1901, he founded a school at Shantiniketan, which later became Visva-Bharati University. The school was based on Tagore’s educational philosophy, which emphasized creativity, freedom, and a close connection with nature. He sought to create an environment where students could develop their full potential in an atmosphere of love and respect.

Tagore’s philosophical ideas continued to evolve during these years. He was deeply influenced by the teachings of the Upanishads, as well as by the works of Western philosophers such as Plato, Immanuel Kant, and John Stuart Mill. His philosophy emphasized the importance of self-realization, the unity of all existence, and the need for a harmonious relationship between the individual and the universe. These ideas found expression not only in his literary works but also in his social and educational initiatives.

The 1890s also saw Tagore’s increasing involvement in the cultural and intellectual life of Bengal. He became a leading figure in the Bengali Renaissance, a period of cultural and intellectual revival in Bengal. He was involved in various literary and cultural societies and contributed to numerous journals and periodicals. His essays from this period explore a wide range of topics, including literature, art, music, and philosophy, reflecting his broad intellectual interests and deep commitment to cultural renewal.

Tagore’s work from this period also reflects his growing awareness of the social and political issues facing India. While he was not directly involved in the nationalist movement at this time, his writings often explored themes of social justice, equality, and the need for reform. He was particularly concerned with the plight of the rural poor and the need to address the social and economic inequalities that plagued Indian society.

By the turn of the century, Rabindranath Tagore had established himself as one of the most important literary and cultural figures in Bengal. His work during this period laid the foundation for his later achievements and reflected his deepening engagement with the philosophical, social, and cultural issues of his time. As he continued to evolve as a writer and thinker, Tagore would go on to make groundbreaking contributions to literature, art, and philosophy on a global scale.

Nobel Prize and International Fame (1901–1921)

The period from 1901 to 1921 was a transformative one for Rabindranath Tagore, both in terms of his literary achievements and his emergence as an international figure. This era saw the publication of some of his most significant works, his winning of the Nobel Prize, and his growing involvement in global cultural and intellectual exchanges.

In 1901, Tagore founded Shantiniketan, a school based on his educational ideals. He envisioned it as a place where students could grow in harmony with nature, free from the rigidities of traditional education. Shantiniketan soon became a center for progressive education, attracting students and teachers who shared Tagore’s vision. The school embodied Tagore’s belief in the importance of holistic education, which nurtured the intellectual, artistic, and spiritual development of individuals. Over time, Shantiniketan grew into Visva Bharati University, an institution that would play a crucial role in fostering cultural exchange and international understanding. Visva-Bharati, which means “the communion of the world with India,” was established with the aim of bringing together the best of Eastern and Western cultural and intellectual traditions. Tagore envisioned the university as a global center of learning where scholars, artists, and students from around the world could come together to explore knowledge and creativity without the constraints of national or cultural boundaries.

During this period, Tagore’s literary output continued to flourish. One of his most significant works from this time is the collection of poems titled Gitanjali (Song Offerings), which was first published in 1910 in Bengali. The poems in Gitanjali reflect Tagore’s deep spirituality and his exploration of the relationship between the individual soul and the divine. The collection is marked by its lyrical beauty and profound philosophical insights, expressing themes of love, devotion, and the search for meaning in life.

In 1912, Tagore translated Gitanjali into English, which brought his work to the attention of the Western world. The English version of Gitanjali was published in 1913 with a preface by the renowned Irish poet W.B. Yeats, who was deeply impressed by the spiritual depth and universal appeal of Tagore’s poetry. The publication of Gitanjali in English marked the beginning of Tagore’s international recognition as a poet and thinker.

In the same year, 1913, Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, making him the first non-European to receive this prestigious honor. The Nobel Committee recognized him “because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh, and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West.” The Nobel Prize brought Tagore global fame, and he became an important cultural ambassador for India.

Tagore’s Nobel Prize marked a turning point in his life, as it opened up new opportunities for international travel and cultural exchange. Over the next several years, Tagore traveled extensively, visiting countries in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. During these travels, he gave lectures, readings, and performances, sharing his ideas on literature, education, and philosophy with audiences around the world. His travels also allowed him to meet and engage with leading intellectuals, artists, and political leaders of the time, including Albert Einstein, Romain Rolland, and H.G. Wells.

Through his travels and interactions with people from diverse cultures, Tagore developed a deep commitment to the idea of universal humanism. He believed that despite the differences in culture, language, and religion, all human beings shared a common humanity that transcended national and cultural boundaries. This belief in the unity of humanity became a central theme in his work and his vision for Visva-Bharati University.

Tagore’s growing international reputation also brought him into contact with the Indian nationalist movement, which was gaining momentum during this period. While Tagore was deeply committed to the cause of India’s independence from British rule, he was also critical of the narrow nationalism that he believed could lead to division and conflict. He advocated for a more inclusive and humanistic approach to nationalism, one that recognized the importance of cultural and intellectual exchange between nations.

In 1919, Tagore made a significant political statement when he renounced the knighthood that had been conferred upon him by the British government in 1915. He took this step as a protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, in which British troops killed hundreds of unarmed Indian civilians. Tagore’s renunciation of the knighthood was a powerful act of defiance and reflected his deep sense of moral responsibility and his commitment to justice and human dignity.

During this period, Tagore continued to write prolifically, producing a wide range of literary works, including poetry, novels, essays, and plays. His work from this time reflects his growing engagement with the social, political, and cultural issues of the day, as well as his deepening philosophical and spiritual insights. Some of his notable works from this period include the novel Gora (1910), which explores themes of identity and nationalism, and the play The Post Office (1912), which is a meditation on life, death, and the human spirit.

By the early 1920s, Rabindranath Tagore had become a global cultural icon, known not only for his literary achievements but also for his contributions to education, social reform, and international understanding. His work during this period laid the foundation for his later endeavors, as he continued to explore the relationship between the individual and society, the local and the global, and the material and the spiritual. As he entered the next phase of his life, Tagore would continue to push the boundaries of his creative and intellectual pursuits, leaving an indelible mark on the world.

Political and Social Contributions (1921–1932)

The years from 1921 to 1932 were marked by Rabindranath Tagore’s deepening involvement in political and social issues, both in India and on the international stage. Although primarily known as a poet and philosopher, Tagore was also a committed social reformer who used his influence to advocate for justice, equality, and human rights.

Tagore’s engagement with political issues during this period was shaped by his commitment to universal humanism and his belief in the importance of cultural and intellectual exchange. He was deeply concerned about the rising tide of nationalism and militarism in the world, which he saw as a threat to global peace and harmony. In response, Tagore advocated for a more inclusive and humanistic approach to politics, one that emphasized the need for dialogue, understanding, and cooperation between nations.

One of the key political events of this period was Tagore’s involvement in the Indian independence movement. Although he was critical of the narrow nationalism espoused by some sections of the movement, he was a vocal critic of British colonial rule and a strong advocate for Indian self-determination. Tagore’s writings and speeches from this period reflect his deep commitment to the cause of Indian independence, as well as his concern for the social and economic well-being of the Indian people.

In 1922, Tagore published a collection of essays titled Creative Unity, in which he outlined his vision for a world based on the principles of justice, equality, and human dignity. In these essays, he argued that true freedom could only be achieved when individuals and nations recognized their interdependence and worked together for the common good. Tagore’s vision of creative unity was rooted in his belief in the fundamental unity of all existence, a theme that runs throughout his work.

Tagore’s commitment to social reform was also evident in his efforts to address the social and economic inequalities that plagued Indian society. He was particularly concerned about the plight of the rural poor, who were often marginalized and oppressed by the dominant social and economic structures. In response, Tagore initiated a number of rural development projects aimed at improving the lives of the rural population.

One of the most significant of these projects was the establishment of the Sriniketan Institute of Rural Reconstruction in 1922. Located near Shantiniketan, Sriniketan was designed to be a center for agricultural education and rural development, where farmers could learn new techniques and methods to improve their livelihoods. Tagore believed that rural development was essential for the overall progress of the nation, and he was deeply committed to empowering the rural population through education and economic development.

Tagore’s work at Sriniketan was part of his broader vision for a self-reliant and socially just India. He believed that true independence could only be achieved when India’s villages were empowered and self-sufficient, and he saw rural development as a key component of this vision. Tagore’s efforts to promote rural development were informed by his deep respect for the dignity of labor and his belief in the importance of community and cooperation.

During this period, Tagore also became increasingly involved in international efforts to promote peace and understanding between nations. He was a vocal critic of the growing militarism and imperialism that he saw as a threat to global stability, and he used his influence to advocate for disarmament and peaceful resolution of conflicts. Tagore’s commitment to peace was reflected in his participation in a number of international conferences and organizations dedicated to promoting dialogue and understanding between nations.

One of the most notable of these efforts was Tagore’s participation in the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations. In 1924, Tagore attended the League’s annual assembly in Geneva, where he delivered a powerful speech calling for greater cooperation and understanding between nations. In his speech, Tagore emphasized the importance of cultural exchange and mutual respect as the foundation for lasting peace. His vision for the League of Nations was one that prioritized human dignity and the well-being of all people, regardless of national or cultural differences.

Tagore’s commitment to internationalism was also evident in his efforts to promote cultural exchange between India and other nations. He believed that art, literature, and music had the power to transcend national boundaries and bring people together. In 1929, he embarked on a tour of Southeast Asia, during which he visited countries such as Indonesia, Malaya, and Burma. The tour was part of Tagore’s broader effort to strengthen cultural ties between India and its Asian neighbors and to promote a sense of shared cultural heritage.

Throughout this period, Tagore continued to write prolifically, producing a wide range of literary works, including poetry, essays, and plays. His work from this time reflects his deepening engagement with the social and political issues of the day, as well as his ongoing exploration of the relationship between the individual and society, the local and the global, and the material and the spiritual.

By the early 1930s, Rabindranath Tagore had established himself as not only a literary giant but also a leading voice for social justice and global harmony. His advocacy for social justice, rural development, and international peace had made him a respected figure not only in India but also across the world. As a thinker, Tagore was ahead of his time, advocating for values that continue to resonate in contemporary discussions on human rights, global peace, and sustainable development.

Tagore’s influence during this period extended far beyond the realm of literature. He was a key figure in the cultural renaissance of Bengal, known as the Bengal Renaissance, which sought to blend traditional Indian culture with modern, progressive ideas from the West. Tagore’s vision for India was one where tradition and modernity could coexist, enriching each other. His efforts to revive and modernize Indian art, literature, and education were part of this broader cultural movement, which sought to redefine Indian identity in the context of a rapidly changing world.

One of Tagore’s most significant contributions during the 1930s was his work on social and economic reform. He continued to focus on the issues of rural poverty and the need for self-sufficiency in Indian villages. His efforts at Sriniketan were aimed at creating a model of rural development that could be replicated across India. Tagore believed that empowering the rural population through education, economic development, and community organization was essential for the overall progress of the nation.

In addition to his work in rural development, Tagore was also deeply involved in addressing social inequalities, particularly those related to caste and gender. He was a strong advocate for the upliftment of women and Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and believed that social reform was essential for achieving true freedom and justice. Tagore’s writings from this period often addressed issues of social inequality, challenging the traditional norms and advocating for a more just and equitable society.

Tagore’s commitment to social justice was also evident in his stance on political issues. While he was a strong advocate for Indian independence, he remained critical of the more militant and exclusionary forms of nationalism that were gaining popularity at the time. Tagore believed that nationalism, when taken to an extreme, could lead to violence, division, and the suppression of individual freedoms. He argued for a more inclusive and humanistic approach to nationalism, one that recognized the importance of cultural diversity and global interconnectedness.

In 1930, Tagore embarked on another international tour, this time focusing on Europe and the United States. During this tour, he gave lectures and readings, sharing his ideas on literature, philosophy, and politics with audiences around the world. Tagore’s speeches from this period reflect his deep concern for the state of the world, particularly the rise of fascism and militarism in Europe. He warned against the dangers of authoritarianism and called for greater cooperation and understanding between nations.

Tagore’s international tours also provided him with the opportunity to strengthen cultural ties between India and other nations. He met with leading intellectuals, artists, and political leaders, including figures like Albert Einstein and Mahatma Gandhi. His interactions with these leaders helped to shape his views on global issues and reinforced his commitment to peace and human rights.

Despite his growing international fame, Tagore remained deeply connected to his roots in Bengal. He continued to write in Bengali, producing some of his most important literary works during this period. His poetry, novels, and essays from the 1930s reflect his ongoing exploration of themes such as love, death, spirituality, and the relationship between the individual and the cosmos. Tagore’s work from this time is marked by its introspective quality, as he sought to understand the deeper meaning of life and the human experience.

One of Tagore’s most significant literary works from the 1930s is the novel Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World), published in 1916 but continuing to gain relevance and attention during this period. The novel explores the complex relationship between personal freedom, social responsibility, and national identity, and it remains one of Tagore’s most widely studied and discussed works. Ghare-Baire reflects Tagore’s concerns about the dangers of extreme nationalism and the impact of political movements on individual lives and relationships.

By the early 1930s, Rabindranath Tagore had become a symbol of India’s rich cultural heritage and its aspirations for a more just and equitable society. His work in literature, education, social reform, and international diplomacy had earned him a place among the most influential thinkers of his time. Tagore’s vision for a world based on the principles of justice, equality, and mutual respect continues to inspire generations of leaders, artists, and thinkers.

As he entered the final decade of his life, Tagore remained committed to his ideals, continuing to write, speak, and advocate for the causes he believed in. His legacy, both in India and around the world, is a testament to the power of ideas and the enduring relevance of his message of love, peace, and universal humanism.

Later Years and Legacy (1932–1941)

The final years of Rabindranath Tagore’s life were a period of reflection, continued creativity, and an unwavering commitment to the ideals he had championed throughout his life. Despite his advancing age and declining health, Tagore remained active in his literary and artistic pursuits, as well as in his efforts to promote social justice, cultural exchange, and international peace.

During the 1930s, Tagore continued to produce a significant body of work, including poetry, essays, and plays. His later poetry is characterized by a profound sense of introspection and a deep engagement with existential questions. Works such as Shesh Lekha (The Last Poems), written in the final months of his life, reflect his thoughts on life, death, and the eternal cycle of creation and destruction. These poems are marked by their lyrical beauty and philosophical depth, offering a poignant reflection on the human condition.

In addition to his literary work, Tagore remained deeply involved in the activities of Visva-Bharati University. He continued to oversee the development of the institution, which had become a symbol of his vision for a global center of learning and cultural exchange. Under Tagore’s guidance, Visva-Bharati attracted students and scholars from around the world, becoming a hub of intellectual and artistic activity. Tagore’s commitment to education as a means of fostering global understanding and cooperation remained one of his most enduring legacies.

Tagore’s later years were also marked by his continued engagement with political and social issues. He remained a vocal critic of British colonial rule in India, and his writings and speeches from this period reflect his deepening concerns about the future of the country. Tagore was particularly critical of the rising tide of communalism and sectarian violence in India, which he saw as a betrayal of the country’s rich cultural heritage and its potential for unity in diversity. He called for a more inclusive and humanistic approach to nationalism, one that recognized the importance of cultural pluralism and mutual respect.

Despite his opposition to British rule, Tagore maintained a nuanced and critical perspective on the Indian nationalist movement. He was deeply concerned about the impact of political violence and the erosion of individual freedoms, and he continued to advocate for nonviolent methods of resistance and social reform. Tagore’s views on nationalism and independence were informed by his belief in the fundamental unity of all humanity and his commitment to the principles of justice and human dignity.

Tagore’s international reputation continued to grow during this period, and he remained an important figure in global cultural and intellectual circles. He continued to travel and engage with thinkers and leaders from around the world, sharing his ideas on literature, philosophy, and politics. His interactions with global intellectuals, including his famous conversations with Albert Einstein, further solidified his reputation as a leading thinker of the 20th century.

In the late 1930s, Tagore’s health began to decline, but he remained active in his creative and intellectual pursuits. He continued to write and paint, exploring new forms of artistic expression and pushing the boundaries of his creativity. Tagore’s later paintings, characterized by their abstract forms and vibrant colors, reflect his ongoing exploration of the relationship between the material and spiritual worlds. His artistic work from this period is considered groundbreaking, as it marked a departure from traditional Indian art forms and embraced a more modern, abstract aesthetic.

Rabindranath Tagore passed away on August 7, 1941, at the age of 80. His death was mourned not only in India but also around the world, as people recognized the passing of one of the greatest literary and cultural figures of the modern era. Tagore’s legacy continues to live on through his vast body of work, his contributions to education and social reform, and his enduring message of love, peace, and universal humanism.

Tagore’s influence on Indian literature, art, and culture is immeasurable. He is considered the greatest Bengali poet and one of the most important literary figures in the world. His works have been translated into numerous languages, and his ideas on education, social reform, and internationalism continue to inspire generations of scholars, artists, and thinkers. Tagore’s vision for a world based on the principles of justice, equality, and mutual respect remains as relevant today as it was during his lifetime.

In India, Tagore is revered as a national treasure, and his contributions to the country’s cultural and intellectual heritage are celebrated in various ways. His songs, known as Rabindra Sangeet, remain an integral part of Bengali culture, and his works are studied in schools and universities across the country. Tagore’s birthday, known as Rabindra Jayanti, is celebrated with great enthusiasm in Bengal and other parts of India, with performances of his music, poetry, and plays.

Visva-Bharati University, which Tagore founded, continues to be a center for learning and cultural exchange, embodying his vision for a global community of scholars and artists. The university remains a living testament to Tagore’s commitment to education, creativity, and the pursuit of knowledge. Tagore’s ideas on education, particularly his emphasis on creativity, and holistic development, have had a profound and lasting impact on educational practices, not only in India but around the world. He believed that education should not be confined to the mere acquisition of knowledge, but should also cultivate a sense of creativity, critical thinking, and moral values. Tagore’s educational philosophy was grounded in the belief that learning should be a joyful and liberating experience, one that nurtures the innate potential of each individual.

Tagore’s emphasis on creativity was evident in the curriculum and pedagogical practices at the school he founded in Shantiniketan, which later grew into Visva-Bharati University. At Shantiniketan, education was seen as a means of fostering artistic expression and personal growth. The curriculum included a wide range of subjects, including literature, music, art, and nature study, all designed to stimulate the imagination and encourage a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world.

One of the key principles of Tagore’s educational philosophy was the integration of the arts into everyday learning. He believed that artistic expression was a fundamental aspect of human experience and that it should be nurtured from an early age. At Shantiniketan, students were encouraged to engage in various forms of artistic expression, including painting, music, dance, and theater. Tagore himself was actively involved in these activities, often writing plays and composing music for the students to perform.

Tagore also placed a strong emphasis on the importance of nature in education. He believed that children should be allowed to learn in an environment that was in harmony with nature, rather than in the rigid and confining atmosphere of traditional classrooms. The open-air classrooms at Shantiniketan were designed to allow students to learn in close contact with the natural world, fostering a sense of connection to the environment and a respect for all living things.

In addition to creativity and nature, Tagore’s educational philosophy was deeply rooted in the idea of holistic development. He believed that education should address not only the intellectual and artistic needs of the individual but also their emotional, moral, and spiritual growth. Tagore saw education as a means of cultivating empathy, compassion, and a sense of social responsibility. He encouraged his students to develop a global perspective, to respect cultural diversity, and to work towards the betterment of society as a whole.

Tagore’s ideas on education were revolutionary for their time and continue to influence educational thought and practice today. His belief in the importance of creativity, nature, and holistic development has found resonance in modern educational approaches, such as the Montessori and Waldorf methods, which also emphasize the importance of fostering creativity and personal growth in a nurturing and supportive environment.

Beyond his contributions to education, Tagore’s legacy extends to his impact on Indian literature, culture, and social reform. As a writer, Tagore’s works have left an indelible mark on Bengali literature and have been translated into many languages, allowing his ideas to reach a global audience. His poetry, novels, and plays continue to be celebrated for their lyrical beauty, philosophical depth, and profound exploration of the human condition.

In the realm of music, Tagore’s influence is equally significant. He composed over 2,000 songs, known as Rabindra Sangeet, which remain an integral part of Bengali culture and are widely performed and cherished. These songs reflect Tagore’s deep love for nature, his spiritual beliefs, and his commitment to social justice. They continue to inspire and uplift audiences, both in India and around the world.

Tagore’s legacy as a social reformer is also noteworthy. He was a vocal advocate for women’s rights, social equality, and the upliftment of marginalized communities. His efforts to address the social and economic challenges faced by India’s rural population, particularly through his work at Sriniketan, have had a lasting impact on rural development in the country. Tagore’s vision for a just and equitable society, where all individuals have the opportunity to reach their full potential, remains a guiding principle for social reformers today.