In the deepest darkness of prehistoric caves, far removed from sunlight and safety, ancient humans painted their stories onto stone walls—bison charging, hands outstretched, symbols of unknown meaning. These images, hidden in labyrinthine tunnels that snake beneath the surface of the Earth, have long been celebrated as humanity’s first great artistic expression. But recent research from a team of archaeologists at Tel Aviv University has added a surprising new layer to our understanding of this primeval legacy. They propose that these ancient cave sites were not just early classrooms or shamanic temples—they were also places where the smallest members of society played a vital spiritual role.

It is a provocative theory, one that challenges the conventional view that prehistoric children were mere observers—passive apprentices in a society shaped entirely by adults. Instead, Dr. Ella Assaf, Dr. Yafit Kedar, and Prof. Ran Barkai suggest that children, especially very young ones, may have been revered as spiritual intermediaries—beings uniquely positioned to communicate with the supernatural forces believed to dwell in the depths of the Earth. Their recent paper, published in the journal Arts, rewrites the script of prehistory and places toddlers and adolescents not on the sidelines, but at the heart of the action.

To understand how this bold hypothesis took shape, we must revisit the world of Upper Paleolithic Europe—roughly 40,000 to 12,000 years ago. This was a time when early Homo sapiens roamed the landscape as hunter-gatherers, navigating a rugged world teeming with life, danger, and mystery. Amid this environment, they began to leave enduring marks on cave walls. Over 400 sites of cave art have been discovered, mainly in France and Spain. These include the famed Chauvet Cave, whose paintings are more than 30,000 years old, and the iconic Lascaux, with its vivid murals of bulls and horses.

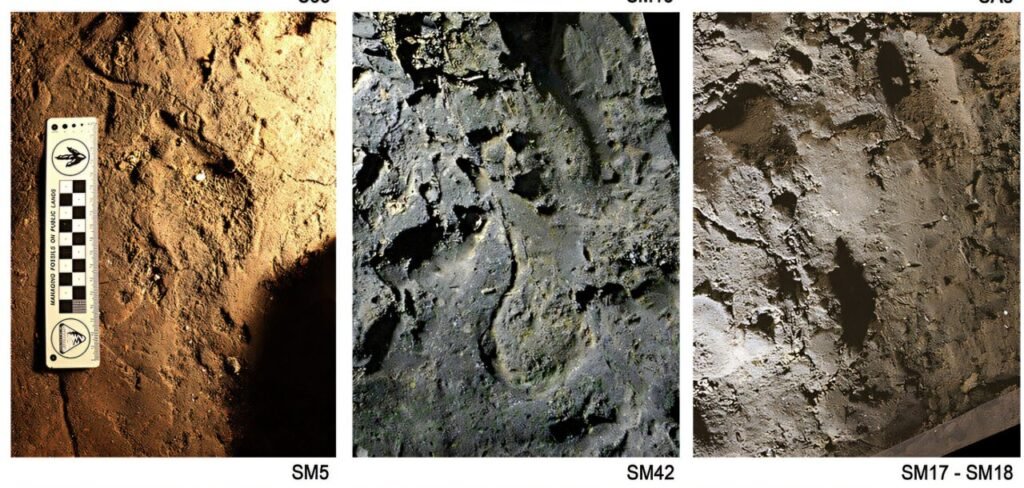

While much has been written about the beauty and symbolism of these works, something has often been overlooked: the fingerprints—literally—of children. Tiny handprints, sometimes just the size of a two-year-old’s palm, adorn walls alongside adult hands. Finger flutings—lines traced by small fingers through soft cave surfaces—abound in various chambers. Footprints of children accompany those of adults in the clay floors. These aren’t just coincidences. They are records of presence. And presence, as this new research argues, implies significance.

What drew young children into such perilous places? The routes to these subterranean galleries were anything but easy. Entering them often meant crawling on hands and knees, squeezing through tight crevices, descending into shafts where oxygen was scarce, and enduring long periods in total darkness. It is hard to imagine any caregiver subjecting toddlers to such trials unless something more profound than mere observation or play was at stake.

Until now, the prevailing academic view has been that children were taken to cave sites as part of an educational tradition—a sort of Paleolithic apprenticeship. In this view, participation in the rituals of cave painting was a way to transmit knowledge, customs, and beliefs across generations. But the Tel Aviv University team believes there is more to the story. Drawing on cross-cultural studies of Indigenous societies, ethnographic records, and recent archaeological findings, they suggest that prehistoric people may have believed that young children held a unique place in the cosmic order.

In many traditional cultures, children—particularly infants and toddlers—are perceived not as incomplete adults, but as liminal beings. Liminality is the state of being “in between”—neither fully part of one realm nor the other. Just as caves were considered thresholds between the human world and the spirit world, children were seen as existing on the threshold between life and pre-life, the material and immaterial, the known and the mysterious.

Because of this, many societies have viewed children as spiritually potent, closer to the origins of life and death, more in tune with unseen realms. In these worldviews, children are not merely immature minds—they are conduits. They are considered especially attuned to the natural and supernatural worlds because their sense of self is still forming. Without the rigid constructs of adult thought, children can perceive and interact with things adults cannot.

From this perspective, the presence of children in the cave painting process was not incidental—it was central. The deep caves were not merely art studios or schools. They were portals. Sacred spaces. Gateways to the underworld or other cosmic dimensions. To reach these realms, communities engaged in ritual activity—often through art, sound, dance, and altered states of consciousness. And who better to accompany the elders and shamans into these netherworlds than the children who, according to cultural beliefs, had only recently emerged from such realms?

The researchers argue that children weren’t just passive witnesses to these rituals. They participated. They painted. They touched the walls. They left their marks—deliberately. The traces they left behind in the form of finger flutings and hand stencils were not mere acts of mimicry. They were spiritual imprints. Gestures of communication. Messages to the unseen.

Dr. Ella Assaf emphasizes that these insights come not only from archaeological evidence but from a synthesis of various disciplines. By studying how modern and historic Indigenous communities around the world treat children in ritual contexts, parallels begin to emerge. From Aboriginal Australian songlines to Amazonian tribal ceremonies, children are often involved in rites meant to connect the community to ancestral spirits, animal guides, or forces of nature. This cross-cultural pattern suggests that viewing children as mystical intermediaries is not a modern romantic notion—it is an ancient human intuition.

Dr. Yafit Kedar elaborates that while the educational explanation for children’s presence in caves is valid, it is incomplete. The new model does not replace the old, but expands it. Children were learning, yes—but they were also doing something else. Something more profound. They were acting within a cosmological framework that assigned them a role beyond their years—a role that gave meaning to their journey through darkness.

This interpretation also shifts how we view the purpose of cave art itself. Rather than simply being a form of storytelling or symbolic communication, the paintings may have been part of a larger ritual process—a way of maintaining relationships with non-human forces. These could include animal spirits, ancestral entities, or even geological or celestial powers believed to reside within the Earth. The caves, in this view, were living spaces, inhabited by more than humans. They were places where boundaries dissolved.

Prof. Ran Barkai takes this further by noting that caves were not just physically underground—they were cosmologically underworld. Many ancient traditions view the Earth as layered, with different realms stacked upon one another. The surface is the domain of humans, but below it lies the world of the dead, the ancestors, the animal spirits, and the gods. Accessing this realm was essential for solving existential dilemmas—ensuring good hunting, healing the sick, seeking guidance.

In such rituals, children were not just allowed to participate. They were required. Their presence was crucial, not in spite of their age, but because of it. The community believed that they could navigate the subtle dimensions where adult logic and perception faltered. They were the voice of innocence, the soul of purity, the antenna tuned to divine frequency. In caves that breathed mystery and echoed with the heartbeat of the Earth, children’s laughter, cries, and handprints were not out of place—they were sacred instruments in a symphony of spiritual survival.

This reimagining of the role of children in cave art not only adds emotional depth to our understanding of prehistory, but it also confronts us with a challenge: to reconsider how we interpret evidence, and how we project modern biases onto ancient people. The assumption that young children were too fragile, passive, or unimportant to be part of ritual life may be a reflection of modern adult-centric thinking, not a reality of prehistoric society.

By placing children back into the center of the Paleolithic spiritual world, this research invites us to see the past not just as a sequence of events, but as a tapestry of relationships—between the living and the dead, the human and the non-human, the old and the young. And in doing so, it paints a fuller, more human picture of our ancestors—not as cold, calculating survivalists, but as people seeking meaning, forging bonds, and trusting the smallest among them to help make sense of the unknown.

As archaeologists continue to illuminate the past with new tools and ideas, the walls of ancient caves still whisper to us—stories of vision, courage, and wonder. And perhaps now, we can also hear the soft voices of children echoing through the chambers, calling across time with open palms and fearless hearts, reminding us that even in the darkest depths, light can be found in the smallest hands.

More information: Ella Assaf et al, Child in Time: Children as Liminal Agents in Upper Paleolithic Decorated Caves, Arts (2025). DOI: 10.3390/arts14020027