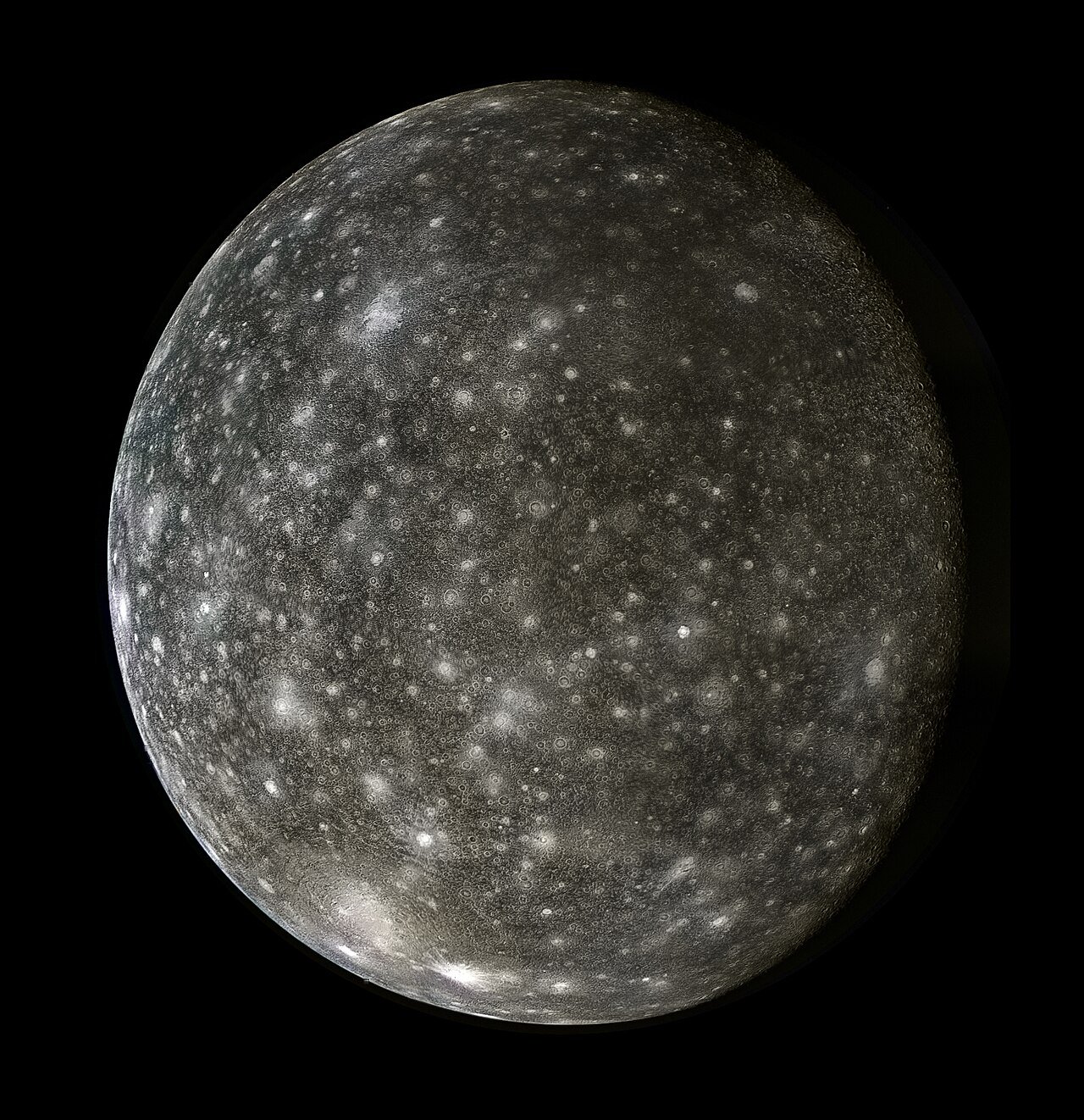

Far beyond the warmth of the Sun, orbiting the gas giant Jupiter, lies a moon that seems to have escaped the restless hand of time. Callisto, the outermost of Jupiter’s four great Galilean moons, is a world both hauntingly beautiful and profoundly ancient—a relic from the dawn of the Solar System, preserved in ice and silence.

When we gaze upon Callisto, we are looking back across more than four billion years of cosmic history. Its cratered surface, untouched by geological renewal, is like an open book recording the story of the early Solar System. Every scar, every ridge, and every frozen plain whispers of an age when planets were still forming, and chaos reigned across the void.

Yet beneath this apparent stillness, Callisto hides secrets that challenge our understanding of habitability, geology, and the potential for life in the most unlikely of places. Though it may appear as a frozen fossil, new evidence suggests that within its icy crust may lie a hidden ocean—a realm of darkness and liquid possibility.

Callisto stands as both a monument and a mystery: an ancient survivor orbiting the mightiest planet in our solar family, watching silently as storms rage across Jupiter’s face and eons drift by like snow upon its frozen plains.

The Discovery of a Distant Companion

The story of Callisto begins in January 1610, when Galileo Galilei turned his telescope toward Jupiter. To his astonishment, he saw four bright points of light near the planet—points that seemed to move from night to night. These were not distant stars but moons orbiting Jupiter, the first celestial bodies ever observed to circle a planet other than Earth.

Among them, Callisto shone as the outermost. Named after a nymph from Greek mythology who was transformed into a bear and placed among the stars by Zeus, Callisto became a symbol of both transformation and endurance.

Galileo’s discovery shattered the old geocentric worldview. It proved that not all celestial bodies revolved around Earth and hinted that our planet might not occupy a privileged place in the cosmos. In that moment, Callisto and its sister moons—Io, Europa, and Ganymede—became heralds of a new scientific era.

For centuries, little more was known about Callisto than its orbit and brightness. But with the arrival of robotic explorers in the 20th century, this distant world began to reveal its ancient secrets.

A Landscape Written in Stone and Ice

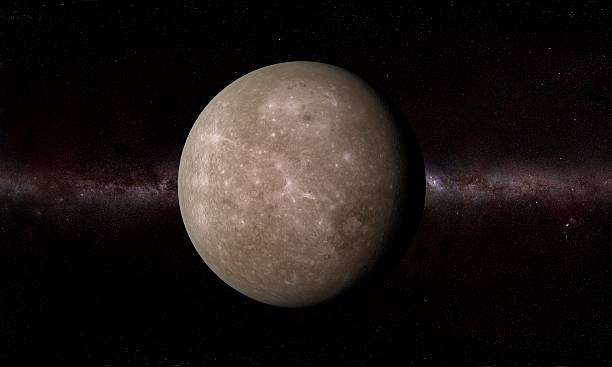

Seen through the eyes of spacecraft, Callisto is a world of endless craters, vast plains, and intricate patterns carved into ice and rock. Its surface is among the most heavily cratered in the Solar System—a dense, chaotic tapestry of impacts accumulated over billions of years. Unlike Earth, whose surface is constantly renewed by tectonics and erosion, Callisto has no such processes to erase its scars. Every crater remains, a permanent monument to cosmic bombardment.

The largest of these features is the Valhalla impact basin, an enormous circular structure about 3,800 kilometers wide—roughly the size of the continental United States. Concentric rings ripple outward from its center like the frozen waves of a stone ocean. Valhalla is a testament to a colossal collision that shook the entire moon, yet somehow did not destroy it.

Another giant basin, Asgard, echoes the same pattern on a slightly smaller scale. The names—drawn from Norse mythology—suit the moon’s mythic, frozen grandeur. From orbit, these impact scars resemble the fingerprints of ancient gods pressed into the ice.

Callisto’s surface composition tells a story of duality. Roughly half rock and half water ice, it glitters faintly under sunlight reflected from Jupiter’s swirling clouds. The ice, darkened by age and radiation, conceals beneath it a crust that may extend for hundreds of kilometers. Despite being bombarded by micrometeorites and bathed in cosmic radiation, the moon’s surface remains surprisingly stable—unchanged for eons.

A Moon Without a Core

Callisto differs profoundly from its three Galilean siblings. Io, closest to Jupiter, is a world of volcanic fire, its surface reshaped constantly by internal heat. Europa hides beneath its icy crust a global ocean warmed by tidal forces. Ganymede, the largest moon in the Solar System, possesses a magnetic field and a differentiated interior of metal and rock.

Callisto, by contrast, appears inert. It is only partially differentiated—its interior has not fully separated into layers of core, mantle, and crust as most large moons and planets have. This indicates that Callisto never experienced the intense heating that transformed its siblings.

The reason lies in its orbit. Being the farthest from Jupiter among the major moons, Callisto is less affected by the planet’s gravitational tides. The tidal flexing that generates internal heat in Io and Europa is negligible here. As a result, Callisto’s interior has remained cold and stable for billions of years—a primordial body preserved in near-original form since the Solar System’s creation.

This makes Callisto a unique scientific treasure. By studying it, scientists can glimpse what the early building blocks of planets were like before geological processes altered them. It is, quite literally, a fossil moon—a preserved record of cosmic infancy.

The Hidden Ocean Beneath the Ice

For decades, Callisto was considered geologically dead, a frozen wasteland incapable of harboring any liquid water. But evidence from spacecraft such as Galileo and later missions challenged that assumption.

Magnetic field measurements taken during Galileo’s flybys revealed something unexpected: the magnetic field around Callisto seemed to fluctuate in a way consistent with the presence of a conductive layer beneath its surface. The most plausible explanation? A subsurface ocean of salty liquid water.

This ocean, if it exists, would likely lie about 100 to 200 kilometers below the surface, sandwiched between layers of ice. Heated faintly by residual radioactive decay and insulated by the thick crust, this hidden sea might have remained liquid for billions of years.

Such a discovery reshapes the definition of habitability. Traditionally, life was thought possible only on warm, Earth-like worlds within a star’s “habitable zone.” But Callisto—and its siblings Europa and Ganymede—show that even in the frozen outer Solar System, life’s potential persists wherever liquid water can endure.

While the likelihood of life on Callisto is lower than on Europa, its deep, stable ocean could still host simple microbial forms, protected from radiation and frozen silence by kilometers of ice. If so, it would mean that even in the coldest reaches of Jupiter’s domain, nature found a way to keep the spark of chemistry alive.

The Atmosphere of Shadows

Callisto’s tenuous atmosphere, or exosphere, is more like a whisper than a true air. Composed mostly of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and traces of hydrogen and other molecules, it is so thin that a single cubic meter of air on Earth contains more particles than an entire cubic kilometer above Callisto.

This wisp of atmosphere exists because molecules slowly escape from the surface ice under bombardment by solar radiation and micrometeorites. It provides no protection from space, no weather, and no winds—only a ghostly veil drifting above the ancient terrain.

Yet even this fragile exosphere is scientifically valuable. It offers clues about the interaction between Jupiter’s powerful magnetosphere and the surfaces of its moons. Charged particles from Jupiter’s radiation belts continuously strike Callisto, sputtering atoms from its surface and creating a dynamic, ever-renewed exosphere.

To human explorers, this radiation poses a serious hazard. Although Callisto lies outside the worst of Jupiter’s magnetic storm belts—unlike Europa or Io—it still experiences levels of radiation far greater than Earth’s natural background. Any human presence would require shielding and protection, though it remains one of the safer Jovian moons for future missions.

The Ancient Record of Impacts

The most striking feature of Callisto’s face is its density of impact craters. Unlike any other large body in the Solar System, Callisto’s surface appears saturated—new impacts overlap the remnants of older ones in a seemingly chaotic mosaic. Scientists call this crater saturation equilibrium—a state where new impacts erase old ones at the same rate they form.

This condition implies staggering age. The surface we see today is likely over four billion years old, dating back to the earliest epochs of planetary formation. It has endured since the era when asteroids and comets bombarded every young planet, shaping their surfaces in a storm of cosmic violence.

Each crater tells a story. The bright ejecta rays radiating from fresh impacts contrast with the darker, weathered terrain of ancient ones. Chains of small craters mark where fragments of a disintegrating comet struck in sequence, reminiscent of the Shoemaker-Levy 9 impact on Jupiter in 1994.

By counting and analyzing these craters, planetary scientists reconstruct the history of impacts across the Solar System. Callisto serves as a benchmark—a frozen archive of the conditions that shaped planets, moons, and asteroids alike. Its surface is not merely static; it is a living timeline written in ice and stone.

The Light of Jupiter

To stand upon Callisto would be to inhabit a realm of perpetual twilight. The Sun, more than five times farther away than it is from Earth, shines dimly, casting long shadows across a landscape of frozen rock. Overhead, Jupiter dominates the sky—a massive, banded giant spanning nearly twelve degrees of arc, twenty times wider than the full Moon appears from Earth.

Jupiter’s glow would bathe Callisto’s plains in a soft amber light, while its four major moons would trace silent paths across the heavens. The night sky here is never truly dark. Reflected sunlight from Jupiter creates a phenomenon known as “Jupiter-shine,” illuminating the landscape even when the Sun dips below the horizon.

Callisto’s orbit keeps it at a respectful distance from its parent planet—about 1.88 million kilometers, the farthest of the Galilean moons. It takes roughly 17 Earth days to complete one orbit. Tidal locking ensures that, like our Moon, the same face of Callisto always points toward Jupiter. From one hemisphere, the planet never sets; from the other, it never rises.

This quiet motion defines Callisto’s existence—a slow, stately waltz in Jupiter’s shadow, eternal and serene.

Exploration Across the Ages

Our understanding of Callisto has evolved through decades of exploration. The Pioneer 10 and 11 missions in the 1970s provided the first close-up views, revealing a heavily cratered world. Later, the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft captured detailed images, confirming the moon’s battered, ancient surface.

But it was NASA’s Galileo orbiter, arriving at Jupiter in 1995, that truly unveiled Callisto’s secrets. Galileo’s instruments measured its composition, gravitational field, and magnetic environment, offering tantalizing evidence of a buried ocean. The images returned showed not only craters but intricate grooves, ridges, and frost deposits—signs of subtle geological processes still at work.

Subsequent missions, including the New Horizons flyby en route to Pluto and the more recent Juno spacecraft, have added new data. And the upcoming European Space Agency mission JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) will study Callisto alongside Europa and Ganymede, probing its surface and subsurface in unprecedented detail.

Through these robotic emissaries, humanity has begun to piece together the story of this frozen world—a story written across billions of years and yet still incomplete.

A Future Base Among the Moons

Because Callisto orbits beyond the most intense radiation zones of Jupiter, it has been proposed as a potential base for future human exploration of the Jovian system. NASA’s conceptual Human Outer Planet Exploration (HOPE) study identified Callisto as a relatively safe harbor—a place to establish habitats, refueling stations, or research outposts for missions deeper into the outer Solar System.

Such a base would allow humans to study Jupiter and its moons remotely, perhaps even deploying robotic probes to Europa or Ganymede. Callisto’s surface materials—ice, rock, and possible oxygen bound in its minerals—could provide water, fuel, and construction resources, reducing dependence on Earth supplies.

Of course, living on Callisto would still be daunting. Temperatures hover around -140°C, and the low gravity (about one-eighth of Earth’s) would pose physiological challenges. Yet the idea captures the human imagination: to stand upon an ancient moon, gazing at Jupiter’s swirling storms, is to witness both the grandeur and fragility of the cosmos.

In a sense, Callisto represents a stepping stone to the outer worlds—a place where humanity could pause, gather strength, and look outward toward Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and beyond.

The Meaning of Stillness

What makes Callisto so compelling is not activity, but absence. In a Solar System full of change—volcanoes on Io, shifting ice on Europa, methane seas on Titan—Callisto is a world at rest. It has not erupted, flowed, or convulsed for billions of years. And yet, in its silence, it speaks volumes.

It reminds us that not all stories are told through motion. Some are written in stillness, in endurance, in the quiet preservation of the past. Callisto’s frozen plains are the Solar System’s memory, untouched by the forces that erase history elsewhere.

Its very name—Callisto, “the most beautiful”—carries an irony and truth. Beauty here does not lie in color or life, but in the solemn dignity of age, the perfection of endurance. It is the beauty of a survivor, an ancient witness that has outlasted storms, impacts, and the passing of worlds.

Lessons from a Frozen Time

Studying Callisto offers insight not only into planetary science but into time itself. Here, geological and cosmic time converge. While Earth’s surface renews itself in cycles of life and destruction, Callisto’s surface is a frozen snapshot of the primordial Solar System.

It helps scientists understand the conditions that led to planet formation—the composition of early materials, the bombardment rates of ancient comets, and the thermal histories of icy bodies. By examining Callisto, researchers refine their models of how moons and planets evolve, and why some remain geologically active while others fall silent.

It also offers a mirror for reflection on our own planet’s fragility. Earth, with its oceans, atmosphere, and life, is the rare exception in a universe of frozen, airless worlds. Callisto’s lifeless plains remind us that the conditions for life are delicate and fleeting—and that the warmth we know may be the briefest flame in an eternal night.

A Portrait of Cosmic Endurance

In the grand symphony of the Solar System, Callisto plays a quiet, persistent note. It is not as dramatic as Io’s volcanic fury, nor as enigmatic as Europa’s hidden ocean, nor as grand as Ganymede’s magnetic power. Yet in its silence lies its strength.

Callisto endures. It has survived every impact, every cosmic storm, every epoch of celestial upheaval. It remains what it was at the beginning—a witness to the birth of planets, the shaping of worlds, and the dance of gravity that continues still.

It is a moon frozen in time, but not forgotten. For scientists, it is a key to understanding the ancient past; for dreamers, it is a symbol of timelessness and survival.

The Eternal Witness

Callisto orbits Jupiter like a patient observer, gazing upon the planet’s storms that rage for centuries, upon the moons that shift and shimmer around it, upon the distant Sun that warms but never melts its icy heart. It has watched for four billion years and will likely watch for four billion more.

If one could stand upon its surface, surrounded by silence deeper than any known on Earth, Jupiter would rise like a colossal guardian in the sky—a reminder that even amid chaos, stability can endure. The faint light from the distant Sun would cast long shadows across the frozen craters, each one a testament to an ancient event now forgotten by time.

Callisto is more than a moon; it is a memory. It is the Solar System’s preserved past, the echo of a time before life, before warmth, before Earth itself took shape.

It endures not because of motion, but because of stillness. And in that stillness lies the purest reflection of eternity—a frozen world orbiting forever beneath Jupiter’s gaze, the ancient moon that time itself could not erase.