For thousands of years, cats have lived among us—purring enigmas perched on windowsills, darting across barn floors, or curling in the warmth of our laps. We often imagine their journey into our homes as an ancient tale of mutual convenience, a silent contract struck between farmers and furtive felines during the Neolithic: you catch our mice, and we’ll tolerate your presence. For decades, this version of feline domestication—cats quietly trailing early agriculturalists into Europe—held sway. But now, two sweeping new studies have swept aside that familiar tale with the force of a lion’s roar.

Instead of passive passengers aboard the agricultural revolution, domestic cats appear to have had a far more complex and culturally charged journey—one that takes us not through Europe’s early grain stores, but through the temples of Egyptian goddesses, the shrines of Greco-Roman deities, and even the longships of Norse raiders. Both studies point to a striking origin point for this saga: Tunisia. Yes, North Africa—not the wheat fields of Neolithic Europe—is emerging as the true cradle of the domestic cat.

In a massive international effort that reads like the collaboration of a United Nations of feline scholarship, researchers from the University of Rome Tor Vergata, working with 42 institutions, and a separate team led by the University of Exeter, partnering with 37 others, have delved deep into the past. They’ve scrutinized thousands of feline bones, sequenced ancient DNA from museum specimens, radiocarbon dated cat remains, and mapped mitochondrial and nuclear markers from prehistoric cat lineages. The result: a scientific sleuthing effort worthy of a detective novel.

Until now, much of what we “knew” about early domestic cats came from studies that leaned heavily on mitochondrial DNA—the easier-to-extract genetic material passed down the maternal line. But this approach had a major flaw: mitochondrial markers are limited in their scope and can’t always distinguish between domestic cats and their wild cousins. And in Europe, where native wildcats once prowled freely, that distinction is crucial. The skeletal features of wild and domestic cats overlap so heavily that bones alone can rarely reveal ancestry. So, earlier interpretations were, in a word, blurry.

The new research brings clarity. Using more powerful techniques—especially paleogenomics, which analyzes nuclear DNA—scientists now trace the definitive entry of domestic cats into Europe not to the Neolithic age, but thousands of years later, during the 1st century CE. That’s during the Roman Empire’s height, when roads crisscrossed continents, temples echoed with chants to many gods, and ships ferried goods, people, and, it seems, cats, across the Mediterranean.

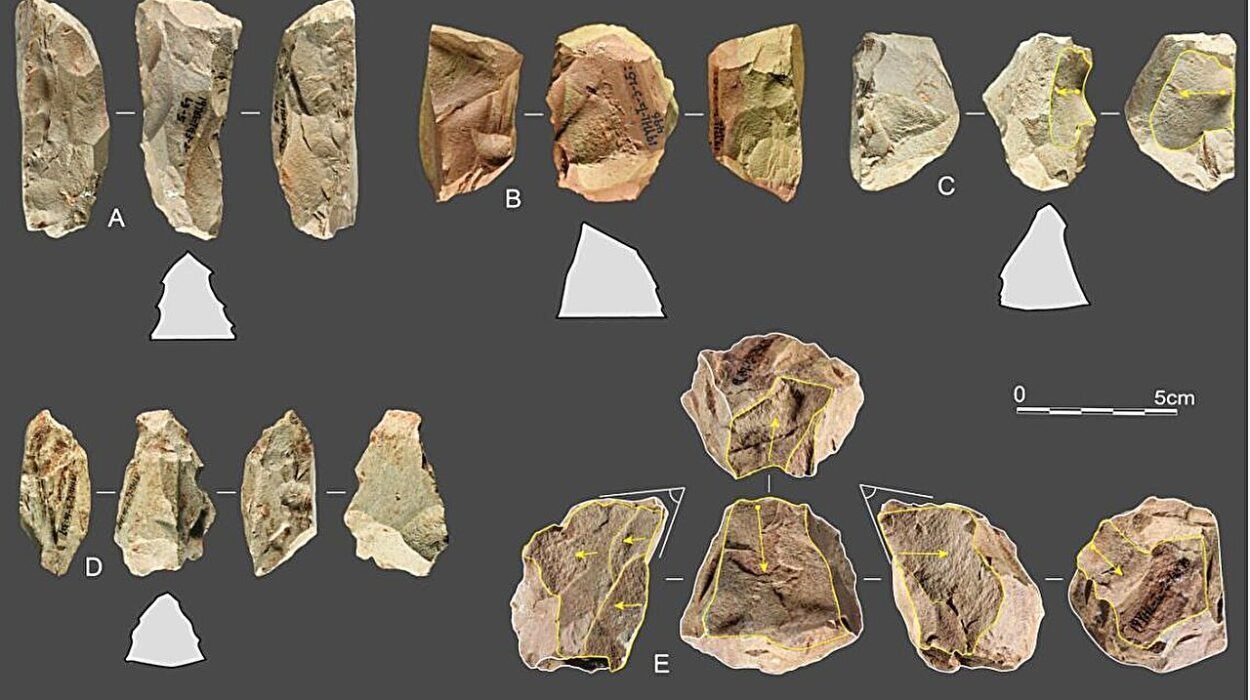

The University of Rome-led study, titled The dispersal of domestic cats from Northern Africa and their introduction to Europe over the last two millennia, drew on ancient cat remains from 97 archaeological sites across Europe and Anatolia. Among these were low-coverage genomes from 70 ancient cats, 17 modern and museum genomes, and 37 radiocarbon-dated specimens. The analyses revealed something striking: domestic cat ancestry appears in Europe only after the 1st century CE, not earlier.

In fact, the team uncovered two key waves of feline migration. The first wave occurred around the 2nd century BCE and brought wildcats from Northwest Africa to Sardinia, which over time evolved into a unique wild population still present on the island today. The second, far more consequential wave took place during the Roman Imperial period, when cats genetically similar to today’s domestic felines spread across Europe, signaling a deliberate movement of domesticated cats—likely from Tunisia.

Meanwhile, the University of Exeter-led study, titled Redefining the timing and circumstances of cat domestication, their dispersal trajectories, and the extirpation of European wildcats, paints a slightly different but complementary picture. Their analysis encompassed an astonishing 2,416 cat bones from 206 archaeological sites. They identified domestic cats in Britain as early as the 4th to 2nd centuries BCE—well before the Romans arrived on the island—hinting at earlier contact through Iron Age trade or migration networks.

By merging morphological analysis with genetic data, the Exeter team confirmed that domestic cats began appearing in Europe by the early first millennium BCE, with successive waves of feline migration continuing through the Roman, Late Antique, and even Viking periods. Despite slight differences in the timeline, both studies align in one remarkable conclusion: Tunisia stands out as a key point of origin, and religious and cultural motivations played a far greater role than mere pest control.

This flips the conventional script. For years, cats were framed as utilitarian hangers-on, valued for their mouse-hunting prowess near grain stores. But these new findings suggest that humans didn’t just tolerate cats—they actively revered them. And that reverence was infectious.

Nowhere is this more evident than in ancient Egypt, where cats were elevated to sacred status. The feline goddess Bastet, depicted with a lioness or domestic cat’s head, symbolized protection, fertility, and motherhood. Cats were mummified by the thousands, buried in sacred cemeteries, and even traded along religious pilgrimage routes. From Egypt, this spiritual enthusiasm likely traveled northward and westward, where Greco-Roman cultures absorbed and repurposed feline iconography. Artemis and Diana, goddesses of the hunt and moon, became associated with cats, mirroring Bastet’s domain over home and hearth.

The reverence didn’t stop with the Mediterranean. Norse mythology features the goddess Freyja, who rode a chariot pulled by two large cats—symbolic of femininity, fertility, and mystery. Cats, it seems, carried with them a powerful spiritual allure that transcended geography. Far from being stowaways, they were emissaries of the divine, traveling with the blessing of goddesses and the awe of civilizations.

Yet as domestic cats arrived in Europe and made themselves at home, not all was harmonious. Native European wildcats, once thriving in forests across the continent, began to decline. The new arrivals—smaller, more sociable, and better adapted to human environments—competed with wildcats for territory and mates. Evidence from both studies suggests that hybridization events became common, with the genetic purity of European wildcats gradually diluted. Disease transmission, competition for food, and shrinking wild habitats only accelerated this trend.

By the first millennium CE, the balance had clearly shifted. Domestic cats had become widespread, and wildcats were increasingly pushed to the margins. Ironically, the very adaptability that helped cats thrive in human societies may have undermined their wild relatives. These were not passive invasions, but complex interactions driven by human choices and cultural shifts.

The implications of these findings are profound. They dismantle the long-held belief that cats were a ubiquitous presence in Neolithic villages. They caution against over-reliance on mitochondrial DNA for tracing ancient animal populations. And perhaps most importantly, they remind us that domestication is not simply a biological process—it’s a cultural one.

Domestication doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It requires selective pressures, yes, but also intention, symbolism, and often, affection. Just as wolves became dogs not just because they guarded camps but because they bonded with humans, so too did cats become domestic not just because they killed rats, but because they captured our imaginations.

Today, over 500 million domestic cats live around the world. They inhabit skyscrapers and farms, alleyways and palaces. They purr on our laps, prowl our streets, and populate our memes. But they carry within them the legacy of a far older, stranger story—one that begins not in Europe’s earliest wheat fields, but in the sunbaked shrines of Tunisia and the gold-limned temples of Egypt.

In peeling back the layers of time, these two groundbreaking studies do more than update a scientific timeline. They reintroduce us to the cat—not just as a pet, but as a historical agent. A creature whose journey was shaped not just by evolution or ecology, but by worship, warfare, trade, and myth. A creature that humans did not merely tolerate, but celebrated. And perhaps that is why, unlike any other domesticated animal, the cat has never fully surrendered its independence. It walks through history—and through our homes—not as a servant, but as a partner. Aloof, mysterious, and utterly unforgettable.

More information: M. De Martino et al, The dispersal of domestic cats from Northern Africa and their introduction to Europe over the last two millennia, biorxiv (2025). DOI: 10.1101/2025.03.28.645893

Sean Doherty et al, Redefining the timing and circumstances of cat domestication, their dispersal trajectories, and the extirpation of European wildcats, biorxiv (2025). DOI: 10.1101/2025.03.28.645877