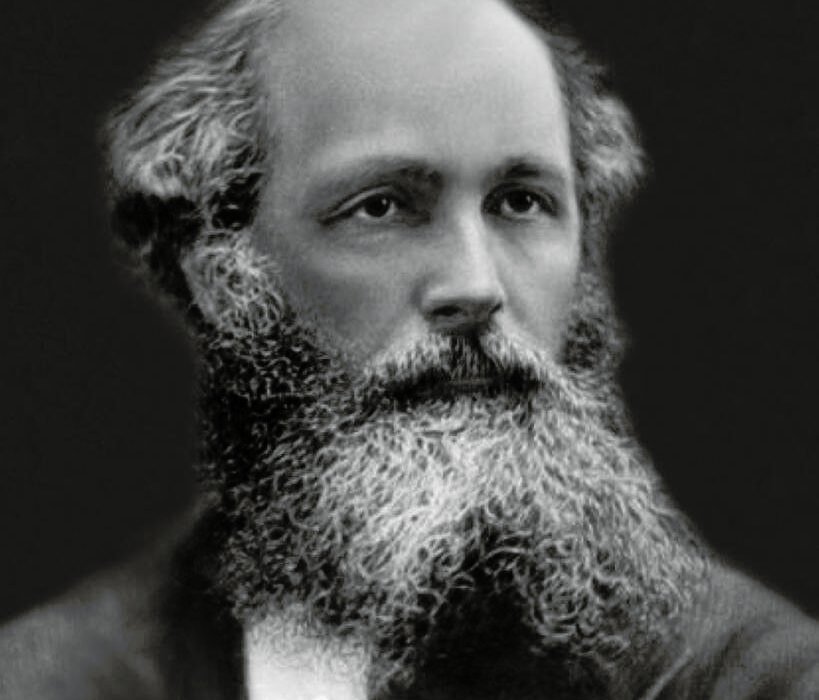

Edward Jenner (1749–1823) was an English physician and scientist renowned for developing the smallpox vaccine, the world’s first vaccine. Born in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, Jenner made a groundbreaking discovery in 1796 when he observed that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox, a much milder disease, were immune to smallpox, a deadly and widespread disease at the time. He tested this by inoculating a young boy with material from a cowpox sore and later exposing him to smallpox, finding that the boy remained healthy. This procedure, which Jenner called “vaccination” (from vacca, the Latin word for cow), laid the foundation for modern immunology and led to the eventual eradication of smallpox. Jenner’s work not only saved countless lives but also revolutionized medicine by introducing the concept of vaccination as a method to prevent infectious diseases. He is often referred to as the “father of immunology.”

Early Life and Education

Edward Jenner was born on May 17, 1749, in the small village of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England. He was the eighth of nine children in a well-respected family; his father, the Reverend Stephen Jenner, was the vicar of Berkeley, a position that provided the family with a stable, though modest, income. Edward’s early years were marked by a deep interest in the natural world, a fascination that would shape his future career in medicine.

From a young age, Jenner exhibited a keen intellect and curiosity. His early education was informal, largely conducted at home under the guidance of his father, who instilled in him a love for learning. This early exposure to scholarly pursuits laid the foundation for his later achievements. After the death of his father when Edward was only five, the responsibility for his upbringing fell largely to his older brother, Stephen, who had also entered the clergy.

At the age of eight, Edward was sent to a grammar school in Wotton-under-Edge, and later to Cirencester, where his academic talents were nurtured. However, it was not until the age of 13 that he began to seriously pursue the study of medicine. In 1763, Jenner was apprenticed to Daniel Ludlow, a respected surgeon in nearby Chipping Sodbury. This apprenticeship was a turning point in Jenner’s life, as it provided him with hands-on experience in medical practice, as well as a deep understanding of the practical aspects of surgery and patient care.

During his apprenticeship, Jenner learned about various medical treatments and procedures, ranging from simple wound care to more complex surgical operations. This period of training exposed him to the harsh realities of 18th-century medicine, where infections were rampant, and mortality rates were high. However, it also instilled in him a sense of purpose and a desire to improve medical practices.

In 1770, after seven years of apprenticeship, Jenner moved to London to further his medical education under the mentorship of John Hunter, one of the most prominent surgeons of the time. Hunter was a pioneering figure in the field of surgery and anatomy, known for his scientific rigor and experimental approach. Under Hunter’s guidance, Jenner honed his skills in anatomy, surgery, and natural history. Hunter’s influence on Jenner was profound, particularly in encouraging him to approach medicine with a scientific mindset, emphasizing observation and experimentation.

Jenner’s time in London was not only a period of intense learning but also one of significant personal growth. He formed relationships with other medical professionals and scholars, which broadened his understanding of the medical field. However, despite the opportunities that London offered, Jenner decided to return to his rural roots in Berkeley after completing his studies. The decision to leave the bustling city life behind and return to the countryside was driven by his desire to practice medicine in a familiar environment, where he could also continue his research into natural history.

Medical Career and Early Research

Upon returning to Berkeley in 1773, Edward Jenner established a general medical practice that served the local population. His decision to work in a rural setting, rather than in a more prestigious urban hospital, reflected his deep connection to his community and his desire to address the health needs of ordinary people. Over the next few years, Jenner became known as a skilled and compassionate physician, treating a wide range of ailments with the limited medical knowledge and tools available at the time.

While practicing medicine, Jenner continued to pursue his interests in natural history and scientific inquiry. He was an avid observer of the natural world, often conducting experiments and collecting specimens of plants, animals, and fossils. This work brought him into contact with other naturalists and scientists, and he became a member of several scientific societies, including the Royal Society, to which he contributed his findings on various topics.

One of Jenner’s early scientific contributions was his research on the cuckoo bird, which led to a significant discovery about the bird’s nesting behavior. He observed that the young cuckoo would push the eggs and chicks of its host out of the nest, a behavior that had not been documented before. This research was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1788, earning Jenner recognition in the scientific community. Although this discovery was unrelated to his later work on vaccination, it demonstrated his keen powers of observation and his ability to draw important conclusions from careful study of natural phenomena.

Jenner’s early medical practice also provided him with opportunities to observe the effects of various diseases, particularly smallpox, which was one of the most feared and deadly diseases of the time. Smallpox epidemics were frequent, and the disease had a high mortality rate, particularly among children. Those who survived were often left with severe scars or blindness. Jenner, like many physicians of his era, sought ways to protect his patients from this devastating illness.

During his practice, Jenner noticed a curious phenomenon: dairymaids who had contracted cowpox, a mild disease that caused pustules on the hands but was otherwise harmless, seemed to be immune to smallpox. This observation was not new—there were long-standing folk beliefs that cowpox could protect against smallpox—but Jenner was among the first to consider the possibility that this immunity could be deliberately induced to prevent smallpox.

The idea of using cowpox to protect against smallpox intrigued Jenner, and he began to consider how this observation could be tested scientifically. He was aware of the practice of variolation, a method of smallpox prevention that involved the deliberate infection of a person with material taken from a smallpox sore. While variolation could confer immunity, it was a dangerous procedure, often causing severe illness or even death. Jenner wondered whether a safer method could be developed using cowpox.

Throughout the 1780s and 1790s, Jenner continued to gather evidence and refine his ideas about cowpox and its potential as a preventive measure against smallpox. His medical practice provided him with numerous cases to study, and he carefully documented his observations. He also communicated with other physicians and scientists to gather information and feedback on his ideas. During this period, Jenner developed a strong belief in the potential of what would later become known as vaccination, though he had yet to formally test his hypothesis.

Jenner’s early research laid the groundwork for what would become his most significant contribution to medicine. His scientific curiosity, combined with his practical experience as a physician, allowed him to approach the problem of smallpox with a unique perspective. His decision to pursue a career in rural medicine, rather than in the more prestigious academic or urban settings, provided him with the opportunity to observe firsthand the health issues faced by ordinary people and to develop practical solutions to these problems.

Development of the Smallpox Vaccine

The development of the smallpox vaccine is perhaps Edward Jenner’s most significant achievement, marking a turning point in medical history. The idea of using cowpox to immunize against smallpox had been circulating for some time, but it was Jenner who systematically tested and documented the process, ultimately proving its effectiveness.

In 1796, Jenner conducted his now-famous experiment. He found a young boy named James Phipps, the son of his gardener, to serve as the subject. On May 14, 1796, Jenner made two small incisions in Phipps’s arm and inserted material taken from a cowpox sore on the hand of Sarah Nelmes, a local milkmaid who had contracted cowpox. Over the next few days, Phipps developed a mild fever and a few pustules, but recovered fully, showing no signs of severe illness.

Several weeks later, Jenner tested Phipps’s immunity to smallpox by inoculating him with material taken from a smallpox sore—a process known as variolation. Remarkably, Phipps did not develop smallpox, demonstrating that the cowpox had indeed conferred immunity. Jenner realized that he had discovered a safer alternative to variolation, which could potentially prevent the deadly disease without the associated risks.

Jenner called his new method “vaccination,” derived from the Latin word vacca, meaning cow, in honor of the cowpox virus that made it possible. He immediately understood the significance of his discovery, recognizing that it could save countless lives by preventing smallpox on a large scale. Over the next few years, Jenner continued to test and refine his vaccination technique, sharing his findings with other medical professionals and refining his methods.

In 1798, Jenner published his findings in a paper titled An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease Discovered in Some of the Western Counties of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of Cow Pox. This work laid out his observations, experiments, and conclusions, providing a detailed account of how vaccination worked and its potential to prevent smallpox. The publication of this paper was a pivotal moment in the history of medicine, as it introduced the concept of vaccination to the world.

Jenner’s work initially met with both interest and skepticism. Some in the medical community were skeptical of his findings, questioning the validity of his experiments and the safety of vaccination. Others, however, quickly recognized the potential of Jenner’s discovery and began to adopt the practice. As word of Jenner’s success spread, vaccination against smallpox began to gain acceptance, first in England and then across Europe. Physicians and public health officials saw the promise of vaccination as a safer and more effective alternative to the older practice of variolation, which, though helpful, still carried significant risks.

As Jenner’s method gained traction, more physicians began to vaccinate their patients, and the technique spread rapidly across Europe. By the early 19th century, vaccination had been introduced in many parts of the world, including North America, India, and other regions of the British Empire. This rapid spread was fueled by both the compelling evidence of its effectiveness and the growing fear of smallpox epidemics, which had previously decimated populations.

Despite its growing popularity, Jenner’s vaccine was not without controversy. Some people were initially fearful of the new method, as it involved the transfer of material from an animal to a human. Critics voiced concerns that it might have unforeseen side effects, and some even spread rumors that vaccinated individuals might develop bovine characteristics, such as horns or a cow-like appearance. Additionally, some religious groups opposed vaccination on moral or theological grounds, arguing that it was unnatural to interfere with the will of God.

In response to these challenges, Jenner worked tirelessly to promote the benefits of vaccination and to counter misinformation. He continued to correspond with medical professionals across Europe and the Americas, providing guidance on how to perform the procedure and sharing the results of further studies that reinforced the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. His commitment to publicizing his work and educating others played a crucial role in overcoming early resistance to vaccination.

As more people received the vaccine and its success became undeniable, governments and public health organizations began to endorse vaccination programs. In 1802, Jenner’s contributions were formally recognized by the British government, which awarded him a grant of £10,000 to further his research and to expand the practice of vaccination. This financial support allowed Jenner to continue his work and to spread the knowledge of vaccination even more widely.

One of the key factors in the success of Jenner’s vaccination campaign was the simplicity of the procedure. Unlike variolation, which required a controlled environment and posed significant risks, vaccination with cowpox was relatively easy to perform and could be done in a wide range of settings. This made it possible to vaccinate large numbers of people, including those in rural or remote areas, where access to medical care was limited.

In the years following Jenner’s initial discovery, vaccination became an integral part of public health efforts to control smallpox. Governments began to establish vaccination programs, and in some cases, vaccination was made mandatory. For instance, in 1807, Bavaria became the first government to introduce compulsory vaccination, setting a precedent that would be followed by many other countries in the decades to come.

The success of Jenner’s vaccine also inspired further research into other vaccines and immunization techniques. Scientists began to explore the possibility of developing vaccines for other infectious diseases, a field of study that would eventually lead to some of the most significant medical advancements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

By the time of Jenner’s death in 1823, vaccination had already saved countless lives and was well on its way to becoming a cornerstone of modern medicine. Jenner himself had lived to see the profound impact of his discovery, and although he faced challenges and opposition, his perseverance ensured that vaccination would become one of the most important tools in the fight against infectious diseases.

Impact of Jenner’s Work on Public Health

Edward Jenner’s development of the smallpox vaccine had a monumental impact on public health, not only in his own time but for generations to come. His work laid the foundation for the field of immunology and revolutionized the way societies approached the prevention of infectious diseases. The ripple effects of Jenner’s contributions extended far beyond the immediate benefits of smallpox prevention, influencing public health policy, medical research, and global health strategies.

Before Jenner’s discovery, smallpox was one of the most feared diseases in the world. Epidemics were frequent and devastating, with mortality rates as high as 30% in some outbreaks. Survivors were often left with disfiguring scars and, in many cases, blindness. The introduction of vaccination dramatically altered the course of the disease, reducing both the incidence and severity of smallpox outbreaks.

The immediate impact of Jenner’s work was seen in the rapid decline of smallpox cases in regions where vaccination was widely adopted. In England, for example, the widespread use of vaccination led to a significant decrease in smallpox-related deaths. As vaccination programs were implemented in other countries, similar reductions in smallpox incidence were observed, demonstrating the universal applicability and effectiveness of Jenner’s method.

The success of vaccination also had broader implications for public health policy. For the first time, governments and health authorities had a reliable tool for preventing a major infectious disease on a large scale. This led to the establishment of organized public health efforts focused on vaccination, including the creation of vaccination clinics, public awareness campaigns, and, in some cases, mandatory vaccination laws. These efforts laid the groundwork for the development of modern public health systems, which continue to play a critical role in disease prevention and control.

Jenner’s work also had a profound impact on the field of immunology. His discovery that exposure to a milder disease (cowpox) could protect against a more severe one (smallpox) was a groundbreaking concept that challenged existing medical theories about disease and immunity. Jenner’s work demonstrated the potential of the immune system to be trained or “educated” to recognize and fight specific pathogens, a concept that would later be expanded upon by scientists such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch.

The development of the smallpox vaccine marked the beginning of a new era in medicine, where the focus shifted from treating diseases to preventing them. Jenner’s success inspired other researchers to explore the possibility of developing vaccines for other infectious diseases. This eventually led to the creation of vaccines for diseases such as rabies, diphtheria, tetanus, and polio, among others. The principles of vaccination established by Jenner continue to underpin vaccine development today, making his work a cornerstone of modern medical science.

In addition to its impact on medicine and public health, Jenner’s work had significant social and economic implications. By reducing the burden of smallpox, vaccination contributed to improvements in overall public health, increased life expectancy, and economic productivity. The ability to prevent smallpox outbreaks meant that fewer people were incapacitated by the disease, reducing the economic costs associated with lost labor, medical care, and social support for those affected by the disease.

The success of vaccination also had important implications for global health. As vaccination programs spread beyond Europe, they played a key role in reducing the global incidence of smallpox. This international spread of vaccination laid the foundation for the eventual eradication of smallpox, a monumental achievement in global public health. In 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an intensified global smallpox eradication campaign, building on the principles established by Jenner nearly two centuries earlier. Thanks to these efforts, smallpox was officially declared eradicated in 1980, making it the first disease to be eliminated through human intervention.

The eradication of smallpox stands as one of the greatest triumphs of modern medicine, and it is a direct legacy of Edward Jenner’s pioneering work. His discovery not only saved millions of lives but also demonstrated the power of science and medicine to conquer even the most formidable diseases. The lessons learned from Jenner’s work continue to inform public health strategies and vaccine development efforts today, as the world faces new challenges such as emerging infectious diseases and pandemics.

Jenner’s impact on public health is immeasurable. His work not only transformed the fight against smallpox but also established the principles of vaccination that continue to protect millions of people from a wide range of infectious diseases. His legacy is reflected in the countless lives saved by vaccines and the continued efforts to develop new vaccines to address the health challenges of the modern world.

Challenges, Criticism, and Acceptance

Despite the revolutionary nature of Edward Jenner’s discovery, the adoption of vaccination was not without challenges. Jenner faced considerable criticism and opposition from various quarters, including segments of the medical community, religious leaders, and the general public. The resistance to vaccination was rooted in a combination of scientific skepticism, cultural beliefs, and fear of the unknown.

In the early years following Jenner’s publication of his findings, many physicians were reluctant to embrace vaccination. Some were skeptical of the efficacy and safety of the cowpox vaccine, questioning whether it truly provided immunity to smallpox or whether Jenner’s results were merely coincidental. This skepticism was compounded by the fact that Jenner’s discovery challenged the established practice of variolation, which had been the primary method of smallpox prevention for centuries. Variolation had its risks, but it was a known quantity, and many physicians were hesitant to abandon it in favor of a new and unproven method.

Furthermore, the medical community of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was still grappling with the basic principles of immunology and infectious diseases. The mechanisms by which vaccination conferred immunity were not well understood at the time, leading to uncertainty and debate about its long-term effects. Some doctors were concerned that vaccination might cause other diseases or have harmful side effects that were not immediately apparent.

Religious and moral objections also played a significant role in the resistance to vaccination. Some religious leaders viewed vaccination as an unnatural intervention that interfered with divine will. The idea of introducing material from an animal into the human body was considered by some to be an affront to the natural order, and there were fears that such a practice could have unintended spiritual or physical consequences. In certain regions, religious leaders actively discouraged their congregations from being vaccinated, leading to a slower uptake of the practice.

Public fear and misinformation further complicated the acceptance of vaccination. Rumors and myths about the dangers of vaccination circulated widely, fueled by a lack of understanding and the sensationalism of early media. Stories about people developing bovine characteristics or suffering severe reactions to the vaccine were common, even though they were unfounded. This misinformation created anxiety and resistance among the general public, leading many people to refuse vaccination for themselves and their children. The fear of the unknown, combined with the novelty of the procedure, made it difficult to convince large segments of the population to accept vaccination, particularly in rural areas where access to reliable medical information was limited.

In response to these challenges, Jenner and his supporters embarked on extensive efforts to educate the public and the medical community about the safety and benefits of vaccination. Jenner wrote numerous letters, pamphlets, and articles aimed at countering misinformation and addressing the concerns of skeptics. He also conducted further experiments to demonstrate the effectiveness of the vaccine, meticulously documenting cases where vaccinated individuals were exposed to smallpox but did not contract the disease.

As evidence of the vaccine’s success continued to accumulate, support for vaccination gradually grew. Many physicians who had initially been skeptical began to embrace the practice as they witnessed its effectiveness in preventing smallpox outbreaks. Prominent figures in the medical community, such as John Hunter and Thomas Dimsdale, endorsed Jenner’s work, lending credibility to the vaccination movement.

Government support also played a crucial role in the wider acceptance of vaccination. Recognizing the potential of Jenner’s discovery to prevent one of the most deadly diseases of the time, several governments began to promote vaccination as a public health measure. In 1800, King Charles IV of Spain initiated one of the first major government-sponsored vaccination campaigns, sending medical teams across the Spanish Empire to vaccinate the population. Similar initiatives were undertaken in other European countries, as well as in the United States, where President Thomas Jefferson became an early advocate of vaccination.

In 1802, the British Parliament awarded Jenner a second grant of £20,000, a significant sum that reflected the government’s recognition of the importance of his work. This financial support allowed Jenner to continue his research and to promote vaccination more broadly, helping to overcome some of the initial resistance he had encountered.

Over time, the overwhelming success of vaccination in controlling smallpox began to speak for itself. As vaccination programs expanded, the incidence of smallpox decreased dramatically in regions where the vaccine was widely used. The clear correlation between vaccination and the reduction of smallpox cases helped to convince even the most skeptical individuals of the vaccine’s efficacy. By the early 19th century, vaccination had become an accepted and widely practiced method of disease prevention, with many countries instituting mandatory vaccination policies to protect their populations.

Despite the eventual widespread acceptance of vaccination, Jenner continued to face criticism from certain quarters throughout his life. Some medical professionals and laypeople remained opposed to vaccination on various grounds, and debates about the ethics and safety of the practice persisted. However, the success of vaccination in reducing smallpox cases and saving lives ultimately outweighed these objections, and Jenner’s work was increasingly recognized as one of the most important contributions to public health in history.

Jenner’s perseverance in the face of opposition and his commitment to scientific rigor played a crucial role in overcoming the challenges he encountered. His ability to engage with skeptics, provide clear evidence of his findings, and communicate the benefits of vaccination helped to ensure the widespread adoption of his life-saving innovation.

Later Life and Legacy

Edward Jenner spent the latter part of his life continuing to advocate for vaccination and furthering his research. Despite his monumental achievement with the smallpox vaccine, Jenner remained modest and focused on his work, never seeking personal fame or wealth from his discovery. He returned to his practice in Berkeley, where he continued to treat patients and pursue his interests in natural history and science.

In addition to his ongoing work on vaccination, Jenner took an active interest in promoting public health more broadly. He became involved in efforts to improve sanitary conditions and prevent the spread of infectious diseases in his community. Jenner’s concern for public health extended beyond his own practice, and he often corresponded with other physicians and public health officials to share his knowledge and insights.

Jenner’s contributions to medicine and public health were widely recognized during his lifetime. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1789, in recognition of his earlier work on the cuckoo bird, and his reputation only grew following the success of the smallpox vaccine. In 1803, the Royal Jennerian Society was founded in London to promote vaccination and to honor Jenner’s work. The society played a key role in organizing vaccination campaigns and in spreading knowledge about the benefits of vaccination throughout the British Empire.

Despite his many achievements, Jenner faced personal challenges in his later years. He suffered from health problems, including a stroke in 1815, which left him partially paralyzed. Nevertheless, he continued to work and to advocate for vaccination until his death. Jenner also experienced the loss of several close family members, including his wife, Catherine, who died in 1815 after a long illness. These personal tragedies deeply affected Jenner, but he remained committed to his scientific and public health work.

Edward Jenner died on January 26, 1823, at the age of 73, at his home in Berkeley. His death marked the end of a remarkable life, but his legacy would continue to influence medicine and public health for centuries to come. Jenner was buried in the chancel of St. Mary’s Church in Berkeley, a simple resting place for a man whose work had such a profound impact on the world.

Jenner’s legacy is most clearly seen in the eventual eradication of smallpox, a goal that was achieved nearly 160 years after his initial discovery. The success of global smallpox eradication efforts, culminating in the World Health Organization’s declaration in 1980 that smallpox had been eradicated, is a testament to the power of Jenner’s innovation. His work laid the foundation for the field of immunology and established the principles of vaccination that continue to protect millions of people from infectious diseases.

In addition to his contributions to medicine, Jenner is remembered for his humility, his dedication to science, and his commitment to improving the lives of others. He was a true pioneer, whose work transcended the boundaries of his time and set the stage for many of the advancements in public health that followed.

Jenner’s name is commemorated in numerous ways, from statues and memorials to the many institutions that bear his name. His home in Berkeley has been preserved as a museum, dedicated to his life and work, and it attracts visitors from around the world who come to learn about the man who changed the course of history.

Global Impact and Long-Term Consequences

The global impact of Edward Jenner’s discovery cannot be overstated. The development of the smallpox vaccine not only saved millions of lives but also set a precedent for the use of vaccination as a public health tool. Jenner’s work paved the way for the development of vaccines for other diseases, leading to some of the most significant advances in medical science.

The immediate consequence of Jenner’s discovery was the dramatic reduction in smallpox cases wherever the vaccine was used. In the years following Jenner’s publication, vaccination campaigns were initiated across Europe, the Americas, and eventually in many other parts of the world. These efforts led to a significant decrease in smallpox mortality, as well as a reduction in the frequency and severity of outbreaks.

As vaccination programs expanded, smallpox began to disappear from many regions, leading to a gradual decline in the global burden of the disease. By the mid-20th century, smallpox had been eliminated from much of the developed world, thanks in large part to the widespread use of the vaccine. The success of these vaccination efforts provided a model for other public health initiatives and demonstrated the feasibility of eradicating a disease through coordinated global action.

The impact of Jenner’s work extended far beyond smallpox. His discovery laid the groundwork for the field of immunology, which has since become one of the most important areas of medical research. The principles of vaccination established by Jenner have been applied to the development of vaccines for a wide range of infectious diseases, including polio, measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, and more. These vaccines have collectively saved millions of lives and have had a profound impact on global health.

The success of vaccination as a public health strategy also had important economic and social consequences. By preventing disease and reducing mortality, vaccination has contributed to improvements in overall health and life expectancy. It has also reduced the economic burden associated with disease outbreaks, including the costs of medical care, lost productivity, and social disruption. The ability to prevent disease through vaccination has played a key role in the development of modern public health systems, which continue to protect populations from a wide range of health threats.

The global impact of Jenner’s work is perhaps best exemplified by the eradication of smallpox, which remains one of the greatest achievements in the history of medicine. The World Health Organization’s smallpox eradication campaign, which began in 1967 and culminated in the official declaration of eradication in 1980, was built on the foundation of Jenner’s work. The success of this campaign demonstrated the power of vaccination to eliminate a disease from the face of the Earth, and it has inspired efforts to eradicate other diseases, such as polio and measles.

The long-term consequences of Jenner’s discovery continue to be felt today. Vaccination remains one of the most effective tools in the fight against infectious diseases, and new vaccines are constantly being developed to address emerging health threats. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, has highlighted the importance of vaccination in controlling the spread of infectious diseases and protecting public health.

Jenner’s legacy is also reflected in the ongoing efforts to expand access to vaccines in low- and middle-income countries. Organizations such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the World Health Organization continue to work towards ensuring that people around the world have access to life-saving vaccines, building on the principles established by Jenner more than two centuries ago.