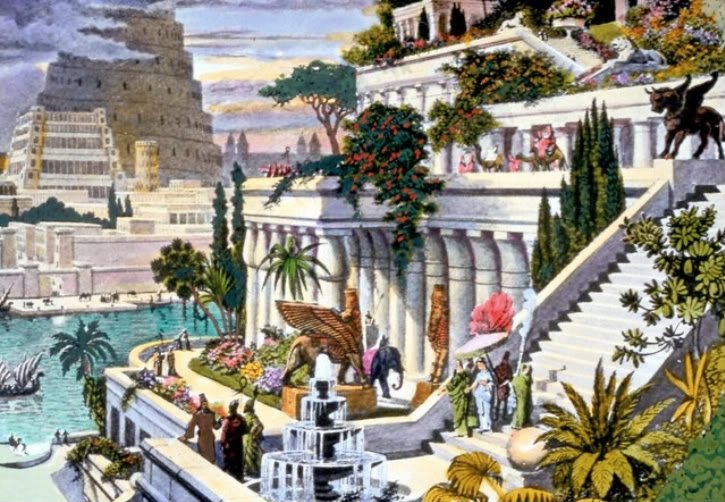

There are few legends as enduring—or as tantalizing—as the tale of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Counted among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Gardens have captured the human imagination for more than two millennia. They are said to have been a breathtaking paradise rising in tiers above the dusty plains of Mesopotamia—a mountain of greenery built by human hands in the heart of the desert.

But here lies the enigma: no archaeological proof of the Gardens has ever been found. No inscriptions from Babylon itself mention them. No ruins, no irrigation systems, no clear evidence—nothing to confirm that they truly existed. And yet, the stories persist. Ancient travelers swore they had seen them. Greek historians described their magnificence in poetic detail.

So, were the Hanging Gardens of Babylon real—a triumph of ancient engineering—or merely a myth born of imagination and longing? The truth lies somewhere between history and legend, in a world where love, power, and ambition could make miracles seem possible.

The World of Babylon

To understand the story of the Hanging Gardens, one must first step into the ancient world of Babylon—a city that once stood as the beating heart of Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq. Founded more than 4,000 years ago along the banks of the Euphrates River, Babylon became one of the greatest cities of the ancient world under the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II in the sixth century BCE.

Babylon was not merely a city; it was a statement of power and splendor. Its massive double walls stretched for kilometers, its streets were wide and straight, and its grand temples honored gods like Marduk and Ishtar. Rising above all was the ziggurat Etemenanki, the temple that some believe inspired the biblical story of the Tower of Babel.

The city was a marvel of architecture, irrigation, and urban planning—a place where human ingenuity transformed barren land into an oasis. It is easy to imagine that within such a civilization, the idea of a vast terraced garden might not have been impossible.

The King and the Queen of Legend

The most famous story of the Gardens’ creation centers on King Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled Babylon from 605 to 562 BCE. According to later accounts, Nebuchadnezzar built the Hanging Gardens for his beloved wife, Queen Amytis of Media.

Amytis, so the story goes, came from the green mountains of the Median Empire (in present-day Iran). When she moved to Babylon, she found the flat, arid landscape unbearably desolate. To ease her homesickness, Nebuchadnezzar ordered the construction of an artificial mountain filled with trees, flowers, and flowing water—a piece of her homeland recreated in the heart of the desert.

It was a gift of love unlike any other: a living monument to beauty and devotion. In the dry heat of Babylon, the Gardens must have seemed like a vision from another world—a lush paradise defying the laws of nature.

The Descriptions of Ancient Witnesses

Though no Babylonian texts describe the Gardens, several Greek historians wrote of them centuries later. Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Quintus Curtius Rufus all left accounts of this wonder, based on older sources and possibly travelers’ tales.

Diodorus Siculus described a garden “built up in terraces, one above another,” supported by massive stone columns and vaulted chambers. The upper terraces were said to contain soil deep enough to grow large trees. Water was drawn from the river below by ingenious means, flowing through channels to irrigate the entire structure.

Strabo added that the Gardens were arranged in ascending tiers, resembling a theater, and that machinery continually lifted water from the Euphrates to the highest level. He described it as a place of “extraordinary beauty,” filled with exotic plants and cool shade—a refuge from the scorching Babylonian sun.

The ancient authors agreed on certain key points: the Gardens were built on terraces; they were irrigated by a complex hydraulic system; and they were unlike anything else in the known world.

But there is one problem: none of these writers ever saw the Gardens themselves. Their accounts were based on second-hand reports, hearsay, and legend—stories already centuries old by their time.

The Missing Evidence

Despite its fame, the Hanging Gardens remain the only Wonder of the Ancient World whose location has never been conclusively identified. Archaeologists have excavated the ruins of Babylon extensively since the nineteenth century, uncovering palaces, temples, walls, and inscriptions. Yet no trace of the Gardens—or their advanced irrigation systems—has ever been found.

This absence is puzzling. If Nebuchadnezzar had indeed built such a monumental structure, surely it would have been mentioned in Babylonian records. The Babylonians were meticulous chroniclers. They recorded building projects, dedicatory inscriptions, and temple restorations with pride and precision. Yet in all the surviving cuneiform tablets from Nebuchadnezzar’s reign, there is not a single mention of a garden built for Amytis.

Even the king’s own writings, which boast of his grand achievements—the Ishtar Gate, the Processional Way, his palaces—say nothing of a terraced paradise. The silence of Babylon’s own records is deafening.

Could the Gardens, then, have been located somewhere else entirely?

The Case for a Mistaken City

In the late twentieth century, a remarkable theory emerged that may finally explain the mystery. British archaeologist Stephanie Dalley of Oxford University proposed that the Hanging Gardens were not in Babylon at all—but in Nineveh, the Assyrian capital 480 kilometers to the north.

Dalley’s research drew on newly translated Assyrian texts, including inscriptions from King Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 BCE). Sennacherib described his palace and gardens in language strikingly similar to Greek accounts of the Hanging Gardens. He even called his creation a “wonder for all people.”

Sennacherib boasted of building an advanced irrigation system, including aqueducts and canals, to bring water from distant mountains to his gardens. Archaeologists have found remains of this system—stone aqueducts, massive channels, and evidence of water-raising devices. One such aqueduct, near modern Jerwan, still bears an inscription crediting Sennacherib with its construction.

Dalley argued that later Greek historians may have confused Nineveh with Babylon after the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Over time, as stories were retold, the memory of Sennacherib’s gardens may have merged with the legend of Nebuchadnezzar’s mighty Babylon, producing the myth we know today.

If Dalley’s theory is correct, the Hanging Gardens may not be a myth at all—they simply stood in the wrong city.

Engineering the Impossible

Whether in Babylon or Nineveh, the creation of such a garden would have been a monumental feat of engineering. The challenge of maintaining a lush, elevated garden in the middle of a dry climate required constant irrigation, structural stability, and vast resources.

Ancient descriptions mention terraces supported by stone columns and vaults. This suggests a multi-level construction, perhaps resembling a ziggurat or stepped pyramid. On each level, thick layers of soil would have been laid to support trees and vegetation. Beneath the soil, bitumen (a type of natural asphalt) and lead sheets may have been used to waterproof the structure and prevent leaks.

The greatest challenge, however, was water. The nearest river—the Euphrates—lay well below the level of the Gardens. To raise water to the upper terraces, the builders would have needed a continuous lifting system.

Some scholars believe they used a device known as a chain pump—a series of buckets attached to a looped chain, turned by a crank or animal power. This would have been centuries ahead of its time, an early precursor to later water-lifting machines like the Archimedes screw.

The scale of such a system, capable of irrigating a multi-level garden, would have made the Hanging Gardens one of the most technologically advanced constructions of the ancient world.

A Living Mountain

The very image of the Hanging Gardens—trees and vines cascading over terraces, waterfalls glittering in the sunlight—captures something profoundly symbolic. In Mesopotamia, a land defined by flat plains and arid deserts, mountains were sacred. They were seen as the dwelling places of gods, the sources of water and fertility.

To build an artificial mountain covered in vegetation was to bring the divine to Earth. It was both a technological triumph and a spiritual gesture—a recreation of paradise itself.

In this sense, the Gardens were not merely decorative. They were a statement of cosmic harmony, linking the heavens and the earth through the art of human hands.

The Wonder That Was

The Hanging Gardens’ fame spread across the ancient world. Poets, travelers, and scholars described them as one of humanity’s greatest creations. They were said to embody the wealth and sophistication of the East—a living contrast to the stone temples and statues of Greece.

By the time of Alexander the Great, the legend of the Gardens was already centuries old. When he conquered Babylon in 331 BCE, the city was still magnificent, though perhaps in decline. Ancient sources suggest that Alexander’s entourage may have seen remnants of the Gardens—or perhaps the palaces and temples that inspired the myth anew.

To the Greeks, the Gardens represented a perfect union of nature and civilization—a testament to human genius and divine beauty intertwined.

Between Myth and Memory

Over the centuries, the legend of the Hanging Gardens has continued to evolve. Artists of the Renaissance painted them as towering palaces covered in ivy and fountains. Poets spoke of them as symbols of love, decadence, and the ephemeral nature of beauty.

Yet beneath the romance lies an enduring question: how does myth begin? Perhaps the Gardens never existed in physical form as the Greeks described. Perhaps they were an ideal, a story born from fragments of memory—bits of truth woven with imagination until they became timeless.

After all, human civilizations often create myths not to deceive, but to preserve meaning. The Hanging Gardens may have been real once, or they may have been an idea too beautiful to fade—a vision of humanity’s eternal longing to shape paradise from chaos.

Rediscovering the Lost Garden

Modern archaeology continues to search for traces of the Hanging Gardens. Excavations in Babylon have revealed vast palace complexes, sophisticated irrigation canals, and evidence of greenery near the royal quarter—but no definitive proof of terraced gardens.

In Nineveh, however, excavations near Sennacherib’s palace have uncovered inscriptions, aqueducts, and ancient reliefs depicting lush landscapes and water channels. These finds lend strong support to the theory that the “Hanging Gardens” may have been part of Sennacherib’s Nineveh, not Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon.

If this is true, then the mystery may finally have an answer—not a myth, but a misremembered marvel.

Lessons from an Ancient Wonder

Whether real or imagined, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon hold a powerful message about human ambition and imagination. They remind us that even in the harshest environments, people have always sought to create beauty, order, and life.

In an age when technology and nature often seem at odds, the idea of the Gardens—a place where engineering serves to sustain living things—feels strikingly modern. They were, in a sense, the first “green architecture,” an ancient experiment in sustainability and aesthetic harmony.

They also speak to the emotional side of creation. If the legend of Amytis is true, the Gardens were not built for power or pride, but for love—the love of one human being longing for home, and another willing to reshape the world to comfort her.

The Echo of Paradise

Even if the Gardens have vanished, their spirit lives on. The idea of a hanging garden—a vertical paradise—has inspired architecture throughout history. From Persian terraced gardens to Roman villa courtyards, from Mughal palaces to modern rooftop gardens, the dream of bringing nature into human spaces endures.

The Hanging Gardens symbolize humanity’s desire to reach upward—to bridge heaven and earth, to tame nature without destroying it, to build beauty that defies decay. They are an echo of our oldest myths, a reflection of Eden, a promise of paradise reclaimed through creativity.

Perhaps that is why they remain so captivating. The Gardens are more than a historical puzzle—they are a metaphor for what it means to be human: to dream beyond limitation, to create against all odds, and to keep seeking beauty even when surrounded by dust.

A Mystery That Endures

Today, the sands of Iraq and northern Mesopotamia hide countless secrets. Beneath them may lie the remnants of terraces once filled with trees and flowers, irrigation pipes long turned to dust, or inscriptions yet undiscovered.

Until that evidence emerges, the Hanging Gardens will remain suspended between reality and myth—a wonder both lost and eternal.

But perhaps that is precisely their power. Not every miracle must leave ruins to be real. Some endure in memory, in art, in the shared longing of generations. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon may never be unearthed, yet they live vividly in the collective imagination of humanity.

They remind us that even in the earliest ages of civilization, people dreamed as we do now—of beauty, of mastery, of love. And though their stone may have crumbled and their trees turned to dust, their story still blooms—ever green, ever alive—in the fertile gardens of the human heart.

The Eternal Bloom of Legend

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon—whether they once stood in stone and soil, or only in story and dream—remain an emblem of wonder. They represent the impossible made real, or perhaps, the real made immortal through imagination.

In their cascading terraces we see the reflection of all that defines us: ingenuity, ambition, devotion, and the longing to build something beautiful in an imperfect world.

And so, when we look upon the modern cities that reach for the sky, crowned with gardens and green towers, we are continuing the legacy of that ancient dream. The Gardens may have been lost to time, but the idea they planted has never ceased to grow.

For as long as humanity endures, so too will the vision of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—a mystery suspended forever between earth and heaven, myth and memory, dream and destiny.