In every culture, stories arise to warn humanity about the perils of arrogance. Yet nowhere does that warning resonate more powerfully than in the myths of ancient Greece. The Greeks, with their deep understanding of human nature, wove into their tales a recurring and tragic theme—hubris, the dangerous overstepping of mortal bounds. To the Greeks, hubris was not mere pride; it was defiance against the gods, a fatal blindness born from the belief that one could rival divinity itself.

In the sunlit world of Mount Olympus, where immortals ruled over every force of life and death, hubris was the greatest sin. It was a spark that ignited downfall, a force that transformed heroes into cautionary legends. Greek mythology is filled with dazzling figures whose brilliance was matched only by their arrogance, whose courage morphed into madness when they forgot the boundary between man and god.

Hubris was not just about pride—it was about imbalance. The Greeks believed the cosmos thrived on harmony, on moderation and respect for natural order. When a mortal sought to rise too high, to claim what was never theirs, the gods would answer with nemesis, the inevitable punishment that restored cosmic balance. Every myth of hubris is, therefore, not merely a tale of downfall—it is a mirror held up to the human soul.

The Meaning of Hubris

To the ancient Greeks, the word hubris carried deeper meaning than its modern translation of “pride” or “arrogance.” It was an ethical and spiritual crime, a kind of moral violence. It meant to dishonor the gods through excessive ambition, to forget the humility that defined humanity. Hubris was not just thinking oneself superior—it was acting as if divine law no longer applied.

Greek tragedies revolved around this concept because it expressed a universal truth: that greatness often carries within it the seeds of its own destruction. When mortals crossed the invisible line between boldness and insolence, between heroism and vanity, they doomed themselves. Their punishment—nemesis—was not always immediate, but it was always certain.

This idea of hubris reflected the Greek worldview: that the universe was governed by justice, order, and balance—known as Dike and Cosmos. To disturb that balance through pride was to invite chaos and destruction. Hubris was not only a crime against the gods, but against the fabric of reality itself.

The Divine Order and the Fragile Mortal

The ancient Greeks believed that gods and mortals occupied separate planes of existence, yet interacted constantly. Mortals depended on the gods for everything—rain, harvest, victory, love, and life. To forget one’s dependence was to commit hubris. The gods, though capable of pettiness and jealousy, embodied powers no human could comprehend. To compare oneself to them was an act of madness.

Yet it was also deeply human. For the Greeks, life was a struggle between fate and free will, between divine law and human desire. The greatest heroes—Achilles, Oedipus, and Odysseus—were not villains. They were extraordinary mortals who reached for greatness, driven by passions that made them both admirable and doomed.

Hubris was thus not only a moral warning but an exploration of the human condition itself. To live without ambition was cowardice; to live with too much was ruin. Between humility and hubris lay the narrow path of wisdom—the path few ever walked successfully.

Icarus and the Wings of Folly

Perhaps no myth captures the essence of hubris more beautifully—or more tragically—than that of Icarus. Born to Daedalus, the master craftsman imprisoned by King Minos on the island of Crete, Icarus was given a miraculous gift: wings fashioned from feathers and wax. With them, father and son could escape their prison and soar into freedom.

But before they took flight, Daedalus warned his son: Fly not too low, or the sea’s spray will weigh you down. Fly not too high, or the sun’s fire will melt your wings. The message was clear—freedom required moderation. But Icarus, young and intoxicated by the thrill of flight, ignored his father’s wisdom.

As he rose higher and higher, the world below shrank into insignificance. The sea glittered like glass, and the sun, radiant and golden, beckoned to him like a god. In that moment, he felt divine—untouchable. But the sun, indifferent to mortal ambition, melted the wax that bound his wings.

Icarus plummeted into the sea, his cries lost to the waves. The ocean that swallowed him became known as the Icarian Sea, a graveyard for the dreamer who dared to fly too close to the sun.

The myth of Icarus is timeless because it speaks to an eternal truth: that ambition without restraint leads to destruction. His flight represents the beauty of human aspiration—but also its peril. We are creatures who dream of the divine, yet our wings are made of fragile wax.

Niobe, the Queen Who Mocked the Gods

If Icarus’s hubris was born of youthful exuberance, Niobe’s was born of royal arrogance. A queen of Thebes and mother to many children, Niobe was blessed with everything a mortal could desire—beauty, power, wealth, and legacy. But her blessings became the root of her downfall.

When the people of Thebes gathered to honor the goddess Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis, Niobe mocked them. Why worship a goddess with only two children when she herself had so many? “I am the true goddess of motherhood,” she boasted, her pride swelling like a storm.

Her words reached the ears of Olympus, and Leto’s divine children descended in fury. Apollo and Artemis, swift and merciless, struck down Niobe’s sons and daughters one by one. The queen, once radiant with pride, watched her legacy crumble in pools of blood and tears.

When the last of her children fell, Niobe fled to Mount Sipylus. There, consumed by grief, she turned to stone. Yet even in her petrified form, legend says, tears continued to flow from her eyes—a river of endless sorrow for her hubris.

Niobe’s story reflects the Greek belief that no mortal, however powerful, could rival the gods. Her pride in motherhood—a noble quality—became her curse when it turned to vanity. The myth reminds us that even the most cherished gifts can destroy us when we forget where they came from.

Arachne, the Weaver Who Challenged Athena

Among the mortals who defied the gods, Arachne stands as one of the boldest and most pitiable. A simple woman of Lydia, Arachne was gifted with extraordinary skill in weaving. Her tapestries were so exquisite that people whispered Athena herself must have taught her. But Arachne, instead of expressing gratitude, denied the goddess’s influence. “I am better than Athena,” she declared.

Such a claim could not go unanswered. Athena, disguised as an old woman, appeared to Arachne and warned her to repent. But Arachne laughed in her face and challenged the goddess to a contest. Both set up their looms, and the battle of artistry began.

Athena wove scenes glorifying the gods’ wisdom and justice. Arachne, daring to mock the divine, depicted their flaws—their deceit, jealousy, and cruelty. Her work was flawless, her artistry beyond compare. Even Athena could not find a fault. But instead of pride, the goddess felt rage, for Arachne’s creation revealed too much truth.

In fury, Athena struck Arachne’s tapestry and cursed her. Overcome with shame, Arachne tried to hang herself, but Athena took pity and transformed her into a spider. Condemned to weave forever, Arachne became the eternal symbol of the artist destroyed by her own pride.

Arachne’s story is not only about defiance but about the cost of revealing divine hypocrisy. In her arrogance, she forgot that truth itself can be dangerous. Her transformation is both punishment and dark immortality—her hubris bound her to the art she loved, but stripped her of her humanity.

Phaethon, the Charioteer of the Sun

Few tales illustrate the fatal beauty of hubris more vividly than that of Phaethon, the son of Helios, the Sun God. Yearning to prove his divine lineage, Phaethon begged his father for a sign—a gift to show the world he was truly the son of light. Helios, bound by an unbreakable oath, granted him any wish.

The boy’s request was simple yet catastrophic: he wished to drive the sun chariot across the sky for a single day. Helios pleaded with him to choose something else, warning that even the gods feared the wild horses of the sun. But Phaethon, consumed by pride, insisted.

At dawn, he grasped the reins and ascended into the heavens. For a moment, the world bathed in glory. But soon the horses sensed the charioteer’s inexperience. They bolted from their path, veering too close to Earth, scorching the deserts of Africa and burning the sky. Mountains smoked, rivers boiled, and the world trembled in fire.

To save creation, Zeus hurled a thunderbolt that struck Phaethon from the sky. His lifeless body fell into the River Eridanus, and the nymphs wept for him. His sisters, mourning by the riverbank, were turned into poplar trees, their tears hardened into amber.

The myth of Phaethon is the story of every soul that overreaches, of every dreamer blinded by the desire to shine. His fall from the heavens is the eternal reminder that even the most radiant ambition must yield to wisdom.

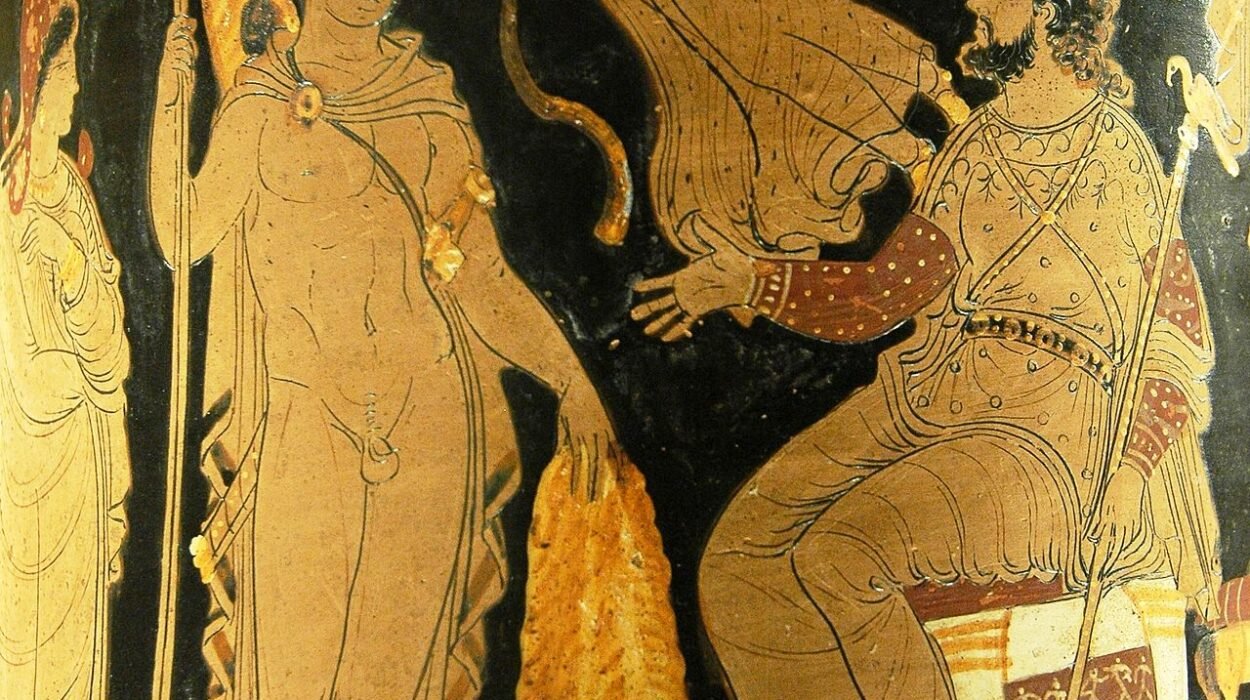

Prometheus, the Defiant Titan

Not all acts of hubris in Greek mythology are villainous. Some, like that of Prometheus, are heroic in their defiance. A Titan who sided with Zeus in the war against his kin, Prometheus was a benefactor of humanity. He taught mankind art, science, and knowledge. But his greatest gift was fire—the divine flame that gave birth to civilization.

Zeus, fearing the power of mortals, forbade fire from being shared with them. Yet Prometheus, moved by compassion, stole a spark from Olympus and brought it to Earth, hidden within a fennel stalk. It was an act of rebellion, an act of love—and an act of hubris.

For his defiance, Zeus condemned Prometheus to eternal torment. He was chained to a lonely rock, where each day an eagle tore out his liver, and each night it grew back. His suffering endured for centuries until Heracles finally freed him.

Prometheus’s hubris was of a different kind—a rebellion born not from vanity, but from moral conviction. He defied tyranny to elevate humankind, embodying the paradox of the human spirit: that to progress, we must sometimes challenge the gods themselves. His punishment mirrors the cost of enlightenment—the pain that often accompanies knowledge and freedom.

Oedipus and the Blindness of Pride

No story captures the tragic nature of hubris more completely than that of Oedipus, the king who sought to outrun fate. When the oracle of Delphi foretold that he would kill his father and marry his mother, Oedipus swore to defy destiny itself. He fled his homeland, determined to thwart the prophecy. Yet in fleeing, he fulfilled it.

Unwittingly, he killed his father, King Laius, in a quarrel on the road. Later, he solved the riddle of the Sphinx, saving Thebes and marrying its widowed queen—his own mother, Jocasta. His intellect, his pride in his own reasoning, blinded him to the truth. When the horror was revealed, he gouged out his eyes, seeing too late what his pride had refused to acknowledge.

Oedipus’s tragedy is not merely about prophecy but about the human refusal to accept limitation. His hubris lay not in malice, but in his belief that he could master fate through intelligence. The Greeks saw in him the reflection of all humanity—brilliant, courageous, yet trapped within the inescapable web of destiny.

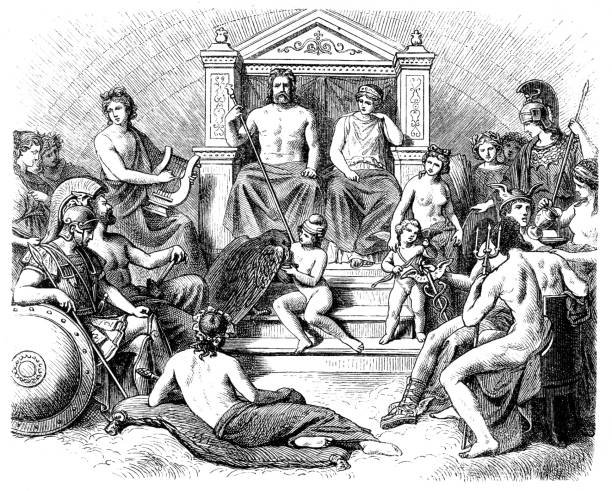

The Gods and Their Jealousy

It is tempting to see the punishment of hubris as cruelty, but in the Greek worldview, it was justice. The gods were not benevolent in the modern sense; they were embodiments of forces that demanded respect. They were the architects of balance, ensuring that no mortal’s flame burned too bright.

Yet the gods themselves were not free from pride. Zeus, Hera, Poseidon—all committed acts of arrogance. But their divinity shielded them from retribution. The Greeks understood this hypocrisy deeply. Their myths suggest that hubris is not the absence of virtue but its excess. Even the divine could be corrupted by it.

This complex morality reflects the Greeks’ understanding of life—not as a battle between good and evil, but between harmony and chaos. Hubris was dangerous because it disrupted that harmony. It was a rebellion against the natural order, a declaration that the self was greater than the whole.

Hubris and the Tragic Hero

Greek tragedy is a theater of hubris. Every tragic hero is defined by the flaw that brings about their fall—the hamartia, or fatal error. But that flaw is never purely evil. It is often the shadow of greatness. The courage that makes Achilles a warrior also makes him defy fate. The intelligence that makes Oedipus a king also blinds him.

Hubris, in this sense, is the inevitable result of human brilliance. To strive, to question, to challenge—these are divine impulses. Yet they are also dangerous. The tragic hero’s downfall is not just punishment; it is revelation. Through suffering, the hero—and the audience—achieves catharsis, a purging of pride through the recognition of truth.

Greek tragedy teaches that hubris is not simply a warning against arrogance—it is a meditation on what it means to be human. To live is to walk the fine line between ambition and humility, between reaching for the stars and remembering the fragility of our wings.

The Modern Echo of Ancient Pride

Though millennia have passed since these myths were first told, the lesson of hubris remains alive. It echoes in every story of power corrupted, in every empire that collapses under its own ambition, in every mind that believes itself beyond consequence.

In science, in politics, in technology, humanity continues to flirt with the boundary of hubris. We build machines that think, weapons that could end us, and systems that defy nature. We fly higher than Icarus ever dreamed, yet the sun still waits above.

The Greeks did not tell these stories to condemn human ambition—they told them to guide it. Hubris is not a command to stop dreaming but a reminder to dream wisely. Every act of creation carries within it the risk of destruction; every quest for power must be tempered by reverence.

The Fragile Balance of Mortality

In the end, hubris is the most human of all flaws. It arises from the same fire that drives us to build, to discover, to love, to defy. Without it, there would be no progress—but with too much, there is only ruin.

The Greeks understood this paradox with haunting clarity. They knew that the human spirit is both magnificent and fragile—that we are divine in our aspirations and mortal in our limits. Their myths endure because they reveal this truth in every fall, every punishment, every tear of stone or drop of wax.

To hear these stories is to feel the pulse of the universe reminding us: greatness without humility becomes self-destruction. The gods may no longer walk among us, but their lesson endures in every human heart.

The Timeless Warning

Hubris in Greek mythology is more than a moral tale—it is a map of the soul. It charts the perilous journey between ignorance and enlightenment, between desire and doom. It whispers that every triumph carries a shadow, and that wisdom begins where pride ends.

The fall of prideful heroes is not meant to humiliate humanity, but to ennoble it. It teaches that our worth lies not in power, but in awareness. The Greeks saw tragedy not as despair, but as revelation—the painful recognition that balance is the essence of existence.

When Icarus fell, when Niobe wept, when Oedipus blinded himself, the world did not end—it learned. And through their suffering, the cosmos was made whole again.

For in the end, every act of hubris is not just a fall from grace—it is a return to truth. And it is there, in that moment of recognition, that mortals remember what the gods have always known: that humility is not weakness, but the highest form of wisdom.